We may be an island nation, but are we a maritime people in our outlook and way of life? It could be reasonably argued that we most definitely aren’t. On last night’s Seascapes, the maritime programme on RTE Radio 1, Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon put forward a theory as to why this should be so. It’s based on a premise so simple that you’d be very confident somebody else must have pointed it out a long time ago. Yet despite Nixon’s notion being in the realms of the bleeding obvious, even with the aid of Google we cannot find any other commentator or historian making a straightforward suggestion along these lines, but will gladly welcome proof to the contrary.

Why aren’t we Irish one of the world’s great seafaring people? After all, we live on one of the most clearly defined islands on the planet. And it’s an island which is strategically located on international sea trading routes, set in the midst of a potentially fish-rich sea. Our coastline, meanwhile, is well blessed with natural havens, many of which are in turn conveniently connected to our hinterland by fine rivers which, in any truly boat-minded society, would naturally form an integrated national waterborne transport system.

Yet the traditional perception of us is as farmers, cattle traders and horse breeders of world standard, while the more modern view would include our growing expertise in information technology and an undoubted talent for high-powered activity in the international aviation industry. Then too, there is our long-established standing in the world of letters and communication and the media generally. Yet although there are now encouraging signs of a healthier attitude towards seafaring and maritime matters, particularly in the Cork region, for most Irish people the thought of a career in the global seafaring and marine industry simply doesn’t come up for consideration at all.

So why is this the case? I think the basic answer could not be simpler. The fact is, nobody ever walked to Ireland. The prehistoric land-bridges to Britain had disappeared before any human habitation occurred here. Our earliest settlers could only have arrived by primitive boat, and that was only ten thousand or so years ago. But even then, boats were still so basic that the often horrific seafaring experiences would have generated the pious hope of having absolutely nothing further to do with the sea and seafaring for the passengers, once they’d got safely ashore. And that attitude was handed down from one generation to the next.

While the south of England, with its land-bridge still connected to continental Europe, had experienced quite advanced human habitations for maybe as long as 400,000 years, Ireland by contrast was one of the very last places in the temperate zones to be taken over by human settlement, and those first settlers must have come by boat of some sort.

So even in terms of the relatively brief period of human existence on Earth, the settlement of Ireland is only the blink of an eye. Thus in talking of “Old Ireland”, we’re talking nonsense. Ireland is a very new place in terms of its human history. Yet although we’ve only been here ten thousand years, all the archaeological research points to the relatively rapid development of a complex society with some very impressive monuments being built in a relatively short period, and by a society which had become highly organised and technologically advanced within a compact timespan. Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange’s location close to the River Boyne (top right) is a reminder that while basic river transport had become quite highly developed, in this era Irish seafaring was still in its earliest and most primitive stages despite the people’s ability to undertake the advanced calculations used in the construction of Newgrange.

So these were not a people who were just passing through. The earliest Irish were determined to make something special of their new home with some colossal and impressive sacred buildings and structures. To some extent this reflected the possibility that they were totally committed to creating a meaningful life in Ireland perhaps because they saw themselves as now marooned on it.

This sense of being marooned would have become embedded and emphasised in the compact family and tribal groups which very slowly spread across the island as a basic farming and hunting people. The inherited memories of the horror of the voyage to attempt to reach Ireland, in which many lives must have been lost at sea, would have been passed down from generation to generation, and we can be sure that the potential hazards of such an enterprise would lose nothing in the re-telling and embellishment of the ancient stories around the family hearth.

In other words, the longer your people have been in Ireland, then the greater would be your inherited sense of the risk in seafaring. Put another way, you could say that the very earliest Irish were not a seafaring people because the very earliest Irish mammies were absolutely determined that their sons were not going to seek a living on the dreadful sea. In the way of Irish mammies, they made sure that everyone knew this, and they have continued to do so to the present day.

If this emphasis on the adverse effect of inherited unhappy memories seems to over-state the case, consider the circumstances of the ancient people of the Canary Islands. When the Spanish voyagers first discovered the Canaries at a time not so very distant from Columbus’s voyages to America, they thought initially that the islands were uninhabited. It was only later that it was discovered that the highest mountain regions were home to an isolated people who were distantly related to the Berbers of North Africa.

In the remote past, these mountain people’s ancestors had somehow – possibly unintentionally – made the 62 mile voyage across from Africa. It is only eight miles further than the shortest distance between Wales and Ireland. But the seas are significantly warmer, which you’d expect to be a favourable circumstance for encouraging further voyaging. Yet having finally struggled ashore, those first Canary Islanders were very soon distancing themselves from the sea and seafaring.

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

Any small enthusiasm they might have had for boats soon disappeared completely, such that they now have no shared knowledge or memory of boats at all. And up in the mountains, their most remarkable talent is the ability to pole vault down into or across the ravines – the Shepherd’s Leap - in order to travel about in their vertiginous homeland, which was seen as preferable in every way to the real dangers of seafaring.

In a Thomas Davis lecture for Seascapes a dozen or so years ago, I discussed the specialised nature of those whose primary interest in the early days of Irish settlement lay in seeing seafaring as a viable way of life. So relatively rare were such people that I reckoned at the time that this talent for exploiting the diverse wealth which the sea offered would provide them with useful survival mechanism for themselves and future generations of their families.

But I now realise that I got it totally wrong. Absolutely the opposite must have been the case. Once you and your people had got safely to Ireland in the first wave of settlers, the seafaring was still so basic and consistently dangerous that having nothing further to do with it was a much better way of ensuring the continuing survival of your genetic stock, whereas producing a family of would-be sailors could see the end of the line in a very short few years.

Although the popular view in Ireland is that our earliest ancestors must have sailed direct from Iberia, it seems to me that Western European seafaring would have been so primitive in those days ten thousand years ago that the first settlers must have voyaged across in nondescript vessels from the most easily reached part of the nearby British land, which is the large island of Islay off southwest Scotland.

As it happens, DNA testing on the current population of southwest Scotland indicates that they too have significant elements of our Iberian stock. Thus there is a shared gene pool, and the earliest Irish most likely came by the easiest route from Scotland, whose people in turn had travelled overland from Europe via England.

If that seems a bit hard to take for those of us who like to think that we’re essentially a Mediterranean people left out in the rain, that we’re essentially a formerly seafaring race who came directly by sea from our ancestral homelands in the Basque region, be consoled by the fact that many centuries later Scotland itself was to undergo conquest by invaders from Ireland of the Scoti tribe, who gave a new name to a country formerly dominated by the Picts.

However, that was very much later, when seafaring technology had greatly advanced, and people could regularly sail across the waters between Ireland and Scotland with some confidence. But when the earliest land-starved pioneers were contemplating crossing to Ireland from Scotland, they would have first looked for the shortest route. The absolute shortest distances between Scotland and northeast Ireland is in the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Fair Head in County Antrim. There, the straight line distance is barely a dozen miles, yet you are facing one of the most tide-riven, roughest and coldest sea channels in Europe. And should you make it safely across, the landing at the nearest point on either side is decidedly difficult.

Further south, the shortest distance between the Mull of Galloway in southwest Scotland across the North Channel to northeast County Down is only 20 miles, but here again in early times the landings were inhospitable on either side, and the tides could be ferocious in their adverse impact.

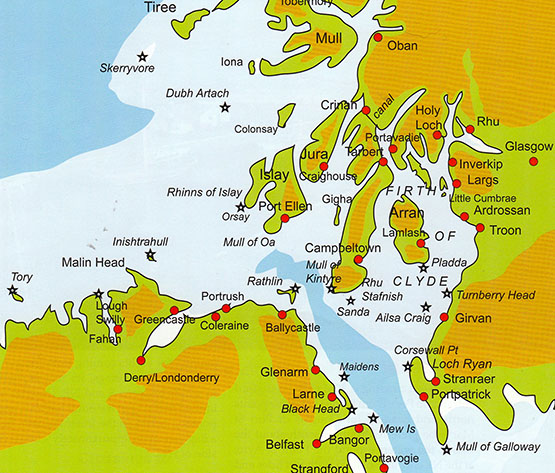

The crossings between Scotland and northeast Ireland which would have been faced by the earliest settlers. While the shortest distance between Kintyre and Fair Head to the east of Ballycastle is just over 12 miles, and the distance between Portpatrick and the nearest part of County Down is barely twenty miles, the entire North Channel between Rathlin Island and the Mull of Galloway is tide-riven, notoriously rough, and with the coldest sea temperatures on the Irish Coast. The earliest voyagers in very primtive boats would thus have had a better chance of a safe crossing, with more options as to their ultimate landfall, by setting off from Port Ellen in Islay, and having avoided the notorious tide race to the southwest of the Mull of Oa, then shaped their course to wherever the winds suited to make a landfall between Inishtrahull and Rathlin. The oldest human settlement in Ireland is at Mount Sandel near Coleraine. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

But if you approached the Scotland-Ireland passage from the mainland of Scotland to the northeast, gradually working your way southwestwards through the southern Hebrides and gaining some seafaring experience with short inter-island hops until you were strategically placed at the natural harbour of what is now Port Ellen on the south shore of Islay, then the prospects were better. You might have still been all of 25 miles from Ireland, but it was a more manageable crossing. You had much greater choice in your possible destinations in making an Irish landfall, as you’d the entire Irish coast from Fair Head to Malin Head to aim for.

In reasonable weather, you could see where you were going, and with prevailing westerly winds there’d be a good chance it would be a relatively easy beam reach if you happened to have a primitive sailing rig, though the likelihood is the early boats were paddled, or rowed in primitive style.

Whatever the method of propulsion, there’s no disputing that one of the oldest sites of human habitation in Ireland is right in the middle of this northern coastline, at Mount Sandel on the River Bann in Coleraine. Yet no matter how much research and archaeology has been undertaken at Mount Sandel and at other ancient sites, no evidence of significant Irish human settlement has been found which goes back any further than ten thousand years.

As it happens, it was ten thousand years ago that mankind first developed the genetic mutation that enabled our ancestors to digest dairy products. But another five thousand years were to elapse before the first cattle were brought to Ireland to find that the place might have been invented for them, and cattle became a source and a measure of wealth. This new socioeconomic development pushed the sea and any form of seafaring even further down the social scale as a viable career option. Who would think of being a fulltime sea fisherman in a land noted as flowing in milk and honey? And even though water transport using rivers became a significant part of Irish life – notably in Fermanagh where the Maguires were to have a water-based mini-Kingdom - the sea was still viewed with suspicion, while the consumption of fish – whether from salt water or fresh – was regarded as socially inferior to eating meat.

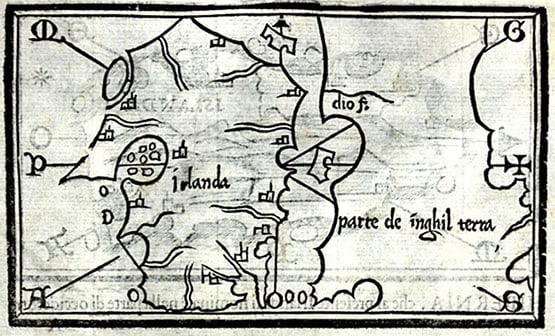

Mediaeval map of Ireland. It’s just possible that the island-studded inlet shown on the west coast is the Maguire-ruled Lough Erne, but more likely it is Clew Bay given prominence through Grace O’Malley.

It was only with improvements in seafaring technology and the general seaworthiness of ships that later generations and new groups of settlers might have brought a more positive attitude towards the sea. Then there was a period of about 1200 years – rudely ended by the first arrival of the Vikings around 795AD – when Ireland was remarkably free of invasions, yet enough marine technology had developed in the island for a brief flowering of Irish seafaring with the extraordinary voyaging of the Irish monks.

It has been argued by some scholars that there was no such person as St Brendan the Navigator. But undoubtedly there were great seafaring monks, and those of us who say that if it wasn’t St Brendan then it was somebody else of the same name will occasionally make the pilgrimage across from Dingle to rugged little Brendan Creek close under the west slopes of Mount Brandon on the north shore of the Dingle Peninsula, and wonder again at those Irish men of limitless faith setting out from this sacred spot into the great unknown in light but able boats.

But as it was seaborne asceticism which they sought rather than wealth, it was seen as a highly specialized and rather odd interest when most of the people were much more readily drawn to epic tales of profitable cattle raiding.

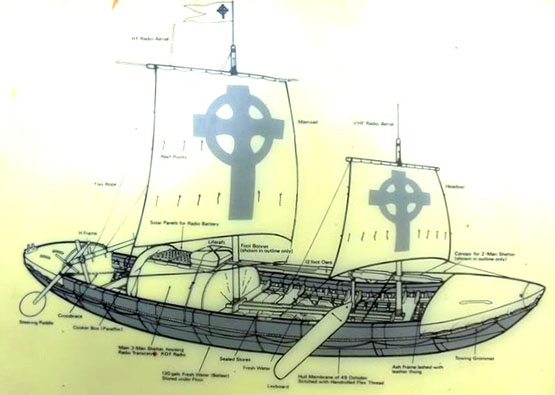

Details of Tim Severin’s oxhide “giant currach” with which – in 1976-77 - he showed that the supposedly mythical Transatlantic voyages of St Brendan the Navigator were technically possible. The St Brendan - which with Denis Doyle’s encouragement was built in Crosshaven Boatyard in 1975-76 – is now on permanent display at Craggaunowen in County Clare.

Then came the Vikings. Say what you like about the Vikings - and everybody has an opinion – but the reality is that their longships represented a quantum leap in naval architecture development. They brought state-of-the-art voyaging in versatile ships way ahead of anything seen before. Yet in time the Vikings were in their turn sucked into the Irish way of doing things, and far from turning Ireland into a seafaring nation, they seem to have literally burned their boats and set up home ashore, gradually absorbing the negative attitude towards the sea of their new neighbours, and taking on board the inevitable anti-seafaring attitudes of their new mothers-in-law

It wasn’t immediately as simple as that, of course. For a while, Ireland was the focal point of the Vikings’ sea trading routes along the coasts of western Europe, while Dublin had the doubtful distinction of being the biggest slave market in the constantly changing Viking western empire, which wasn’t really a territorial empire in the traditional sense, but was more a sphere of active influence and commercial and raiding activity. But it was undoubtedly a major centre which was totally dominated by all Viking activities, including ship-building, and the return to Dublin in 2006 of the 100ft Sea Stallion of Glendalough, a re-creation of one of the biggest Viking ships ever built (in Dublin in 1042), was a telling reminder of just how much Dublin had been to the fore in Viking life, while this video is a timely reminder of the great project completed in Roskilde ten years ago.

Inevitably, people of Viking descent were becoming a significant element in the Irish population, and even today we would naturally expect someone called Doyle to have something of the sea in their veins. Yet the Irish capacity for absorption of newcomers into the old ways of thinking has worked here too. The most common Irish surname today is Murphy. It means sea warrior. While those of us with maritime interests in mind would like to think it referred to an ancient tribe who went forth from Ireland to do successful battle on distant seas, we know in our heart of hearts that the Murphys are descended from warriors – mostly Vikings - who came in from the sea.

In time, they were enticed into domesticity by comely maidens who in due course became the formidable Irish mammies who prohibited any seafaring by their sons. Indeed, so far are most Murphys removed today from the sea that in some parts of the world the name is still a patronising nickname for the potato, something which is useful enough in its way, but its only maritime link is through fish and chips.

After the Vikings and then the Normans – who were really only Vikings with some slightly less rough French manners put on them – subsequent invasions were English-dominated, and the growth of British sea power was done in a manner which made sure that any Irish role in it was strictly of a subservient nature.

Rockfleet Castle in County Mayo, reputed deathplace of Grace O’Malley in June 1603. She was everything she shouldn’t have been, and in heroic style. She was Irish yet a mighty seafarer in command of her own ships, and a woman, yet a ruthless ruler of power and wealth who could combat men on equal terms.

Of course there were local heroes who tried to oppose this, the most renowned being Grace O’Malley, the Sea Queen of Connacht. But even when people of English descent tried to establish a separate Irish seafaring identity, as happened with the merchants of Drogheda, their aspirations would be slapped down by the dominant power and control from the government in London and the influence of the merchants of Bristol.

However, the government only had to look the other way for a moment before there was some local maritime enterprise was trying to flourish, and in the late 18th and early 19th Century the North Dublin smugglers, privateers and pirates of the little port of Rush in Fingal, people like Luke Ryan and James Mathews, were pace-setters in Europe and across the Atlantic, striking deals with Benjamin Franklin among others.

Depending on the state of international hostilities, sometimes their privateering trade could be quite open, and in Dublin the Freeman’s Journal of 23rd February 1779 reported that “we find the little fishing village of Rush has already fitted out four vessels, and one of them is now in Dublin at Rogerson’s Quay, ready to sail, being completely armed and manned, carrying 14 carriage guns and 60 of as brave hands as any in Europe”.

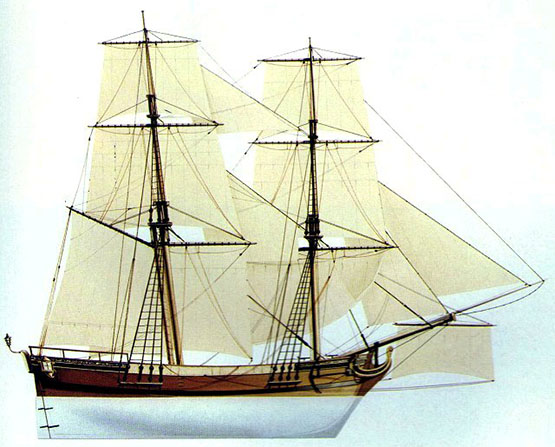

A late 19th century privateer, built for speed. When times were good for privateering, the little port of Rush in Fingal could provide a flotilla of these craft, which at other times could be kept hidden in the Rogerstown Estuary

The Admiral from Mayo. Being press-ganged by the Royal Navy was one of the many career-changing events which resulted in William Brown from Foxford becoming the founder-Admiral of the Argentine Navy.

But the majority of Irish seafarers were employed only in the humblest roles afloat, and often through the activities of the shore-raiding involuntary recruitment drives of the press gangs of Britain’s Royal Navy, However, this could produce some wonderful examples of unexpected consequences. The most complex was William Brown, of Foxford in Mayo, who had somehow risen to be a Captain in the American merchant marine when he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy, and after many vicissitudes, he ended up as a merchant in Buenos Aires. There, thanks to his unexpected acquisition of experience in naval warfare by courtesy of the Royal Navy, he became the founder of the Argentine Navy and an Admiral, as one does…..

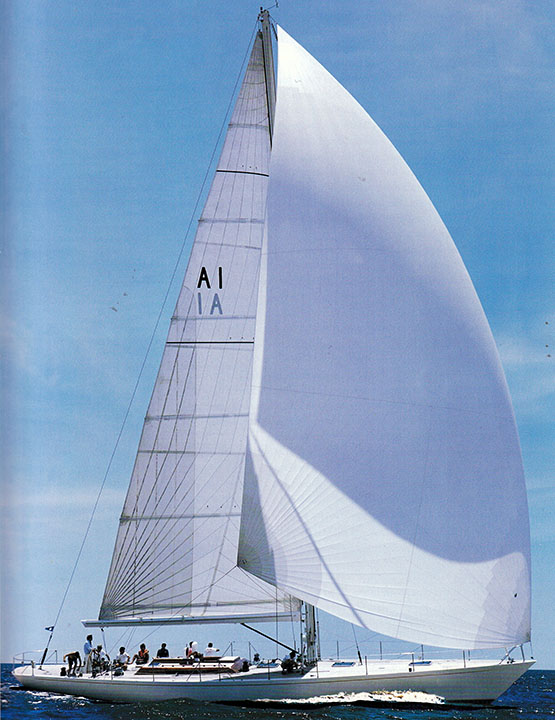

Then there was the 18th Century Patrick Lynch of Galway, …….according to some stories, he was press-ganged. Be that as it may, the family made their fortune eventually in South America and a descendant, Patricio Lynch, owned the ship Heroina which played a significant role in Argentine history. The family continued to prosper in many directions, such that one decendant was Che Guevara, while another is the yacht designer German Frers, whose own pet yacht (which he gets little enough opportunity to use, as he is so busy designing boats for others) is called Heriona in honour of the family’s complex historic links through the sea with Ireland.

Yacht designer German Frers sailing his personal 74ft sloop Heroina in the River Plate. The boat is named in honour of the historic ship which belonged to his ancestor Patricio Lynch.

But while a very few of the young Irishmen press-ganged by the Royal Navy may ultimately have prospered in unexpected ways, the vast majority most definitely didn’t. Most came to a horrible end, while those who had managed to escape the press gangs’ clutches, together with the rest of the bulk of the native population, were reinforced in their inherited distrust of seafaring in any form.

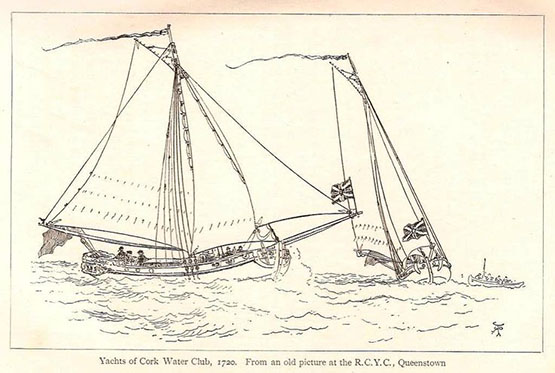

Thus although we may now feel pride in the fact that the world’s first recreational sailing club was established with the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that those great Munster landowners and merchants who founded it were partly doing it subconsciously just to show how very different they were from the ordinary run of Irish people in their attitude to the sea.

First instance of the “have nots” and the “have yachts”? The establishment of the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720 was a remarkable achievement, but if anything it emphasised the fact that the vast majority of Irish people had no enthusiasm or capability for the sea. Courtesy RCYC.

As for the official attitude when the Irish Free State finally came into being, its was so painfully sea-blind that we still need to draw a veil over its attitude, only noting that the first significant voyage under the new Irish ensign was made by one of that much-maligned class, a yachtsman. This was the great venture round the world south of the capes by Conor O’Brien of Limerick with his little Baltimore-built Saoirse between 1923 and 1925.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departs Dun Laoghaire on her world- girding voyage on 20th June 1923.

O’Brien was to find Ireland so stultifying in its outlook after his return that he sailed away to live elsewhere, and we have to accept that for several decades the official approach reinforced the notion that being interested in the sea is un-Irish. So if we hope to change this attitude which still lingers today, a useful first step is to accept that for many of us, being non-maritime is the most natural thing in the world – we’ve had it instinctively from the very beginning, it’s in our handed-down and repeatedly-instilled inherited memories from the time when our most distant ancestors struggled ashore from battered little boats somewhere on the north coast, knowing that many others had died, and would die, trying to do the same thing.

Far from trying to pretend that this attitude doesn’t really exist, surely a much better way is to accept that it does, but that we’ve researched a perfectly valid explanation as to why this is so. Thus the way forward for Ireland to fulfill her maritime potential is to realize why this attitude is there in us, and take mature steps to offset it.

The fact is, in dealing with the sea, the Irish people have never had a level playing field. We’ve had to live with it and our inherited memories of being on it in very adverse circumstances. Unlike continental land dwellers, we have had no choice in the matter - we don’t see the sea as somewhere excitingly new with endless possibilities, we see it only with inherited distrust. And the determination of the current wave of walking migrants from the Middle East into Europe to attempt the sea crossing at only the narrowest part is further dreadful evidence of this.

But in another area of human endeavour, we’ve shown that we can do the business in competition with other nations. When aviation began to become part of everyday life a hundred years ago, it was unknown territory for all mankind. In terms of getting to grips with flying, it was a level playing field for all.

Yet here we are now in Ireland, an island in the Atlantic which is playing an extraordinarily active and central role in many aspects of aviation management and development, and certainly punching way above our weight. Looking at what we have been able to do in the air, it is surely time to look again at what we might do with the sea if we can look at it from a fresh perspective, and adapt the same can-do energies of the Irish aviation industry to the business of seafaring.

It’s time and more to shake off the old fears of the sea, while always maintaining a healthy respect for its undoubted power. That is best done by being in the vanguard of maritime technological development. And down around Cork Harbour, they’re doing that very thing. It’s just possible that, despite our ingrained anti-maritime attitude, we are beginning to view the sea in a more healthy and positive way. And it’s from our great southern port that we’re beginning to get inspiring leadership as the sea beckons us towards fresh opportunities.

So what, if nobody ever walked to Ireland? So what, if our distant ancestors had a very cold, very wet and very rough time getting here? It’s time to move on. Time to get over it. Time to start seeing the sea in a sensible way.

The little ship that carried the maritime hopes of a new nation. Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse in dry dock, showing the tough little hull that was able to register a good mileage most days in the Southern Ocean while still sailing in comfort. Yet when he returned to Dun Laoghaire in 1925 to complete his voyage with a rapturous homecoming reception, Conor O’Brien was soon to find that beneath the welcome there was increasing official indifference in the new Free State to Ireland’s maritime potential.