Maybe it’s time and more to see sailing and its story – and particularly the complex history of Irish sailing north and south – in a new light. This year, the historical sailing focus is on Northern Ireland, where the Royal Ulster Yacht Club and Carrickfergus Sailing Club are both celebrating their 150th Anniversaries. For RUYC, this has already resulted in a Royal visit in recent days. But it was a Royal visit with a difference. W M Nixon takes a look at how the sailing celebration scene in Northern Ireland is reflecting an increasingly nuanced interaction with our sailing history, and how this in turn can affect how we interpret the story of sailing.

It was certainly a Royal visit with a difference, as it usually is with Princess Anne. Whatever your views on Royalty in any of its manifestations, purposes and functions, it has to be accepted that this is one very hard-working member of the British Royal family. When she’s President or Patron of some national or international organisation, it will almost inevitably be because she’s personally interested in the activities involved. And being an involved and can-do person, rather than a stand-aloof sort of figurehead, you’ll find that she was, and probably still is, a very enthusiastic participant in at least some specialized activity within the broad spectrum of the organisation’s remit.

Thus the fact that she and her husband are keen cruising enthusiasts who have in recent years moved up to the Rustler 44 Ballochbuie – which they base in Scotland - after many years with a Rustler 36, means that her role as President of the Royal Yachting Association is something with real meaning. When she goes to a yacht or sailing club, while inevitably there’ll be that slightly giddy mood which always accompanies the presence of Royalty, there’s no escaping the fact that this is a working visit. It’s a long way from being purely ceremonial – people find themselves talking about their own sailing, and sailing in general, both how it is run, and where it is going.

Serious business. Princess Anne in earnest discussion with Gordon Finlay, RUYC Honorary Archivist. On the left is Peter Ronaldson, former Vice Commodore RUYC and former Commodore Irish Cruising Club.

This isn’t the first time in Ireland north and south that Irish sailing has experienced the inspirational results of involvement by the Princess Royal. Twelve years ago, early in 2004, Afloat and the ISA got the word that a Big Idea floated some time earlier might just have wings.

In those days, our annual “Sailor of the Year” and “Sailors of the Month” awards were on a much more commercial basis, as they were strongly sponsored by Cork Dry Gin. It may now seem light years away, that a drinks company could so publically sponsor a major sports awards ceremony. But such was the case – they’d been doing it since 1996.

By 2004 it had become a very smoothly-organised affair, staged in the Irish Distillers Jameson Centre in Dublin where they even have a usefully-sized theatre/cinema which was ideal for this ceremony, and very efficiently organized as an event with Deirdre Farrrell, Irish Distillers’ in-house PR person, skillfully pulling it all together. Afloat and the Irish Sailing Association provided the details on who got what in the awards area, and Paddy Boyd, Secretary General of the ISA, performed as an extremely competent Master of Ceremonies while my job in concert with David O’Brien was to enumerate each of the citations for the usual multiplicity of awardees.

Thanks to the enthusiastic and directly-involved support of the sponsors, this annual show became such a byword for a well-run and popular yet efficiently-controlled event that we found ourselves playing a role in the much wider national and international scene.

The often difficult relations between the Republic of Ireland and Britain had started to thaw quite markedly after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and it was obvious that for this normalization process to continue to develop in a meaningful way which would have a resonance for many points of view within Ireland, in due course a Royal Visit to Ireland by the Queen would have to be on the cards.

So the buildup towards such a visit was set in place with quiet appearances at some relatively low key events – international charities were very useful for this – by some minor members of the Royal Family. The process then moved on, and when someone in the ISA/Afloat setup suggested that in order to add that extra zing to the annual Irish sailing awards, we should ask the Princess Royal in her capacity as President of the UK’s Royal yachting Association to do the honours, ISA President John Crebbin and Paddy Boyd made a discreet enquiry to the British Embassy, and found they were pushing at an open door.

Irish sailing’s idea fitted in very neatly with the development and implementation of improvements in Anglo-Irish relations. In a remarkably short space of time, what had been shaping up as the usual awards ceremony at Irish Distillers in February 2004, to present the gongs for 2003 including Sailor of the Year, had been re-shaped as a Royal occasion, while retaining the basics of the proven annual ceremony to provide an event in which everyone could feel at ease.

Back in February 2004, Irish sailing was given the Royal treatment in Dublin

For that’s what happened. It all went as smooth as clockwork. Deirdre Farrell was in her element keeping it all nicely but gently under control, while Paddy Boyd’s outlining of Royal protoocal beforehand, and his smooth running of the on-stage happenings, would have made you think he had a second life as some sort of big cheese in the United Nations.

As our double-page spread from the March 2004 Afloat suggests, just about everyone was there, they all had their chance of a word or two – and sometimes many – with the Royal President of the RYA, and then we had to canter through a multiplicity of awards with more appropriate words on stage at each juncture, followed by the presentation of the top trophy, which for 2003 was a double, as it was for Noel Butler and Stephen Campion, new World Champions of the International Laser 2 Class.

The RUYC clubhouse was built in 18 months in 1898-1899

The Princess Royal’s visit this past week to the Royal Ulster clubhouse in Bangor was a very different affair, as she was honouring the clubhouse as much as the club and the history to which it is home. In fact, the RUYC carries so much history that you’d wonder they aren’t burdened with it. But they wear their sometimes colourful past remarkable past lightly, for the creation in Bangor, over an ongoing process since 1984, of one of Ireland’s largest marinas, with all amenities including a boatyard, has meant that Belfast Lough and in particular Bangor sailing can move confidently through the present and on into the future, as dinghy sailors’ needs are superbly met by Ballyholme Yacht Club on the most easterly of Bangor’s notable bays.

This means that while today’s Bangor sailors can see the two clubs of RUYC and BYC as the natural focal points which meet their contemporary social needs, in the case of the RUYC clubhouse, it can double as a really remarkable sailing museum. Among other things, it includes the Lipton Room, filled with fascinating memorabilia of the hyper-energetic millionaire Thomas Lipton, who made no less than five challenges for the America’s Cup through the RUYC between 1899 and 1930.

The eternal challenger – Thomas Lipton campaigned for the America;s Cup five times through the RUYC between 1899 and 1930

For the Royal sailing visitor, study time in the Lipton Room provided a vivid insight into one aspect of RUYC history. But then, after the meeting and greeting session with a diversity of members including RUYC Archivist Gordon Finlay and RUYC Historian Ed Wheeler, who are battling with a mountain of incredible material, the visit to the club was rounded out by the presentation to the Princess Royal by Vice Commodore Myles Lindsay of a legendary cruising book which she assured everyone will be going straight into the bookshelf aboard Ballochbuie.

RUYC Historian Ed Wheeler with his wife Jan in a lighter moment with the Royal visitor

The immediately-cherished book was Letters from High Latitudes, published in 1856 as an account of the voyage by Lord Dufferin (his family seat is Clandeboye near Bangor) to Iceland, Jan Mayen and Spitzbergen in the schooner Foam. It has long been a classic of cruising literature, and it still reads today as crisply as though it was written only last week. For Frederick Temple-Hamilton-Blackwood (1826-1902), who eventually became the Marquess of Dufferin & Ava, was a very able sailor and navigator in addition to being a noted diplomat and imperial administrator and excellent raconteur..

So when a few Belfast Lough sailors got together to form the Ulster Yacht Club in 1866, naturally they asked the local national sailing celebrity, this special man who had voyaged to Iceland and beyond ten years earlier, to become its first Commodore, and he in turn ensured that the new club of which he was senior officer became the Royal Ulster YC in 1869.

Lord Dufferin’s Foam, which he sailed to the High Arctic in 1856. He was Commodore RUYC 1866 to 1902.

At first they did without a clubhouse as the sought to serve all the more significant sailors throughout the north of Ireland. But by 1872 they rented some premises on Bangor seafront, and then in 1876 they took a lease on a substantial if semi-detached house on an eminence above the eastern side of Bangor Bay.

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, sailing in Belfast Lough was beginning to take off with local confidence, for before that leading northern sailors such as Henry Crawford with the cruiser-racing yawl Nixie, and John Mullholland - later Lord Dunleath - with the schooner Egeria, had tended to cut a dash elsewhere, Crawford on Dublin Bay, and Mulholland also on Dublin Bay, but even more so in the Solent.

However, by 1890, things were changing very rapidly to bring Belfast and Belfast Lough to the forefront of sailing, and this year’s 150th Celebrations at both Carrickfergus and Bangor – the official title is “Sesquicentennial”, since you ask – make us want to know more.

We’re going through such a plethora of major anniversaries these days – both national and international – that it’s natural there should be growing public interest in the story behind the story, the in-depth background to the history. We now want to know more about some great event way beyond the fact that it merely happened at a certain date, and that by doing so it had some significant outcome.

The much-travelled and very successful racing schooner Egeria was built in 1865 for John Mulholland. The following year, he became the first Vice Commodore of Royal Ulster YC

It may well be that one of the reasons sailing is a sport which is lacking in general public resonance is because histories of sailing have tended to concentrate on the narrow narrative of the development of the sport, and the boats it inspires. As for information on the sport’s administrative history, this tends to be no more than closely focused accounts of how clubs and national organisations emerged to meet the growing demands of this new recreational activity, without setting such developments in a broader framework.

Of course, there are many people who go sailing simply to “get away from it all”, for it’s an activity so different from shore life that the mere fact of being on a boat which is sailing is to be conveyed into another world. Such people may well prefer that the history of their beloved escapist sport is kept aloof from the socioeconomic circumstances in which it exists, and the context in which it developed.

But for others, it enriches our experience of sailing to know how it came to be as it is today, and this year in Northern Ireland there are sailing events and commemorations taking place which, when their back-story is analysed in some depth, give us a much better understanding of the way we live today, and how we go afloat today, and it is in turn all set in a meaningful way in the context of the general historical narrative.

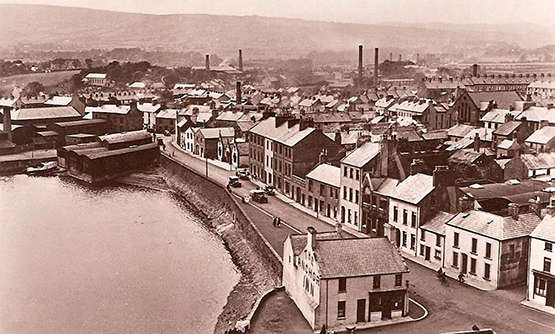

In the case of Belfast in 1890, it was suddenly becoming the Mumbai of its day. It may have been the most air-polluted industrial city in the world, but my word they didn’t linger when doing things, as they had the world’s biggest shipyard, the world’s biggest engineering works, the world’s biggest ropeworks, and the world’s biggest linen mills.

It was the sort of place where a bright and energetic young man with some innovative idea in manufacture could make a fortune well within ten years. Indeed, if you weren’t clearly cutting the mustard within two to three years, it was thought you weren’t really in competition at all.

Yet all this was happening in a rapidly-expanding place which had only been accorded city status as recently as 1886, and its famous new-Classical City Hall, the building which still best symbolizes Belfast’s self-image today, was not completed until 1906.

However, all this growth and wealth-creation was taking place in a city which was dominated by the Presbyterian ethos, which had in effect become the northern “state religion” after the Anglican Church of Ireland was disestablished in 1869.

This meant that while there was wealth about, extravagant expenditure on personal enjoyment was frowned upon, and this extended to sailing as to most other things. But the rapidly-rising Belfast area’s middle classes soon found a way of minimizing expenditure while maximizing their yachts sizes and sailing sport.

Some time in 1895, the Belfast Lough One Design Association came into being. Its membership was open to members of any of the half dozen or so clubs now dotted around the lough including the RUYC itself, and its objective was the simple one of creating economical yet effective one design keelboat classes suitable for the sometimes quite demanding conditions to be found in Belfast Lough.

The pioneers of the BLODA persuaded the great Scottish designer William Fife to create them a sweet but able little 15ftLWL keelboat, just 23ft LOA, for 1896, when the first three were racing. And by that time, the Association had become much more clearly structured, as its Honorary Secretary was one James Craig Jnr, aged only 25 but already noted as a formidable organiser.

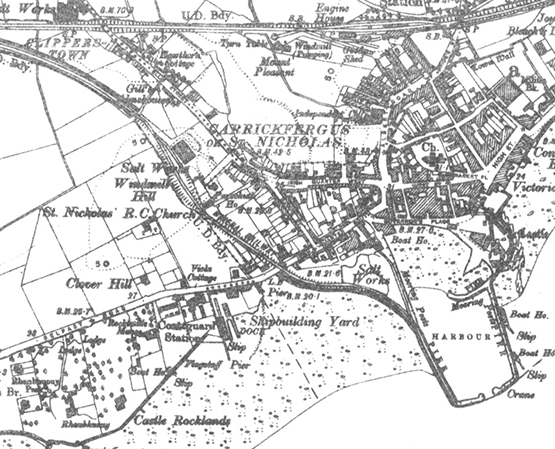

Carrickfergus around 1901. John Hilditch’s first boatyard in 1889 was in the inner harbour where it says “Boat Shed”, then in 1902 he moved to the former shipyard of Paul Rodgers immediately west of the harbour. At the time, Carrickfergus Amateur Rowing & Sailng Club (founded 1866) was in premises on the east side of the East Pier, the more northerly of the two Boat Houses.

In later life he would become Lord Craigavon, first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in 1921. But in 1896 his prime interest was in expanding the 15ft LWL class with an up-and-coming new boatbuilder, John Hilditch of Carrickfergus. Hilditch was very much in Craig’s sights as the approved builder, as he and his men had already shown with the building of the 35ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894 that he could stick rigidly to the designer’s drawings, whereas Paddy McKeown, the back-street boatbuilder in Belfast who built the first three 15ft LWL boats, was notorious for always trying to improve on the designer’s original ideas.

The true pioneers. The Fife-designed 15ft Belfast Lough ODs of 1896 showed the way for the 25ft LWL Class I boats in 1897.

But in the fast-moving world of Belfast in the mid-1890s. events overtook them. Several of the more affluent Belfast Lough yachtsmen had already noted with approval the able seagoing power and attractive performance of the first three 15ft LWL boats. In effect, Belfast Lough provided them with a perfect test tank, and the 15ft LWL boats were their “test models”. In a very short space of time, the heavy hitters in the BLODA had persuaded the Association to order the plans of a 37.5ft LOA, 25ft LWL boats, and thanks to the efficiency of the Hilditch Yachtyard – which in those days was only a few sheds at the head of Carrickfergus Harbour - the first eight boats of the BLOD Class I were racing. They made a huge impact in a visit to the Firth of Clyde in 1897, they went to Dublin Bay where they inspired the creation the following year of the DBSC 25ft OD, and even though at season’s end, when the weekly magazine Yachting World - in reviewing their success - described them as “a cheap knockabout class”, a laudatory report in the influential New York Times of their doings at Clyde Fortnight in Scotland was to carry them through with fresh confidence into their greatest year, 1898.

The humble birthplace. The new BLOD Class I boats were built with remarkable efficiency by John Hlditch and his team in the little boatyard in those black sheds on the inner corner of Carrickcfergus Harbour in the wintyer of 1896-97.

In all their glory. The BLOD Class I boats racing in full strength in 1898.

But anyone who is into Centenaries will realise that Belfast in 1898 had become a very different place from Belfast in 1798. In 1798, Belfast had been a hotbed of the United Irishmen, and one of the local leaders in The Rising, the Presbyterian Henry Joy McCracken, had been hanged with The Rising’s suppression, executed in the town centre on public land which had been donated to the citizens of Belfast by his own grandfather.

In addition to his many other interests, McCracken had been a very early pioneer in developing Belfast Lough sailing, and he and his friends cruised most summers to the west coast of Scotland. But while McCracken may have been taken, his friends lived on in an increasingly different Belfast in the early 1800s, where successful trade and manufacturing industry obliterated any earlier political idealism. Nevertheless some of those former shipmates of Henry Joy McCracken formed the Northern Yacht Club on Belfast Lough in 1820. But as Belfast port became ever more industrialised, they found it more congenial to sail on the Firth of Clyde, within a few years there was a Scottish branch, and by 1838 the Royal Northern Yacht Club of Rothesay had completely absorbed its Belfast unit, and there wasn’t to be another yacht club on Belfast Lough until Holywood yacht Club came into being beside its drying anchorage at the little County Down town immediately east of Belfast in 1862.

By the end of the 1860s, the Holywood club had been joined by the clubs at Carrickfergus and the Royal Ulster, but some years were to pass before the sport of sailing came central stage. Yet by 1898, Belfast Lough sailing wasn’t just centre stage on Befast Lough. It was world-leading. The Fife-designed One Design classes were widely admired at a time when Fife’s star was very much in the ascendant, and then in August 1898, Thomas Lipton announced his first challenge for the America’s Cup through RUYC, the actual contest to take place in New York harbour early in October 1899.

Already, there was a movement among members to build a proper trophy clubhouse for the RUYC, and Lipton made it clear he was unenthusiastic about having his challenge based on a club which was head-quartered in a semi-detached suburban house. But James Craig had a talented older brother who was an architect, Vincent Craig, and he soon had the plans drawn up for an arts & craft building which continues to dominate the Bangor waterfront today, and houses a priceless collection of yachting memorabilia, while at the same providing a convivial venue to celebrate an important Sesquicentennal.

Thomas Lipton’s Shamrock IV of 1914 was one of his most promising challengers. But the outbreak of the Great War signalled the end of the Golden Era, and though Shamrock IV finally challenged unsuccessfuly in 1920, in was in very subdued circumstances.

Today, we know that none of Lipton’s Americas Cup campaigns succeeded, though some came tantalisingly close to success. Today, we know that John Hilditch’s wonderful boatyard only lasted for 24 years, and the poor man, worn down by overwork and finacial stress, died on Christmas Eve 1913. And today we know that, regardless of the turmoil within Ireland from 1912 to 1922, it was the Great War of 1914-1918 which was to wipe out the cream of an entire generation from the north of Ireland, with sports like sailing taking a very long time to recover, if they ever really did recover until much more modern times.

Yet in 1898, it was a time of such hope, such anticipation, such planning – such excitement and exuberance. It can all be captured again with the many events at Royal Ulster and Carrickfergus this summer, when in addition to the clubs’ 150th anniversaries, they’re also staging a Hilditch Regatta at Carrickfergus with a Parade of Sail to Bangor to give proper prominence to the memory of a man who contributed so much to the success of Belfast Lough sailing in the Golden Era of 1894 to 1914.