The Erskine Childers-led Howth and Wicklow gun-runnings of July 1914 took place so quickly and efficiently that those involved ashore only had fleeting glimpses of the boats involved. Although Erskine & Molly Childers’ historic ketch Asgard is now conserved and comfortably at home in the museum at Collins Barracks in Dublin, much less is known or remembered of the other four vessels which took part. W M Nixon takes a look at a line of research which has taken a leap of the imagination to visualise one of these mysterious craft.

You only have to visit the conserved Asgard in Collins Barracks in Dublin to get a true sense of the past, and the special nature of this fine yacht. You grow into an understanding of how it was that people of the utmost respectability, people who sailed one of the best cruising yachts of her era, willingly led themselves and their friends and other yachts into a successful gun-running venture just before the Great War broke out.

That Great War gave everyone the message, loud and clear, that guns are for killing people, they’re not for fun. Yet grim and all as the ultimate message may be, Asgard herself is reassuringly peaceful. And if you have the good fortune to be in a group beside the Asgard listening to a talk by ship conserver John Kearon of how the project of saving the Asgard was achieved, you find yourself in a different world of respect for ancient objects, and a sense of promise for the future.

But in other times and other places, curiosity about the other boats involved inevitably surface. We know from photos of the time what the tug Gladiator looked like - she brought the guns to the Ruytigen Lightship off the Belgian coast to be collected by Asgard and Conor O’Brien’s Kelpie from Foynes. Asgard we know, and as for Kelpie, we have some photos to reveal she was a boat of her time, a hefty 29-ton 1871-built cutter which O’Brien fitted with a ketch rig for easier handling.

As to what happened to her subsequently, we know he used her during his brief period as a fisheries inspector off the west coast when he was employed by the underground government of the nascent Irish state, a government which functioned in a secret parallel universe in opposition to the supposed seat of power in Dublin Castle.

But by 1922, O’Brien was a free agent again, and he took Kelpie away for a mountaineering expedition to Skye off Scotland’s west coast. Returning single-handed through the North Channel in light airs and poor visibility, he slept through an alarm clock’s ringing tones, and Kelpie came gently ashore on the steep Scottish coast south of Portpatrick.

Kelpie as pictured by Jack Finucane of Foynes Island, who sailed as crew with Conor O’Brien

Kelpie as pictured by Jack Finucane of Foynes Island, who sailed as crew with Conor O’Brien

Conor O’Brien and his sister Margret aboard Kelpie off Ireland’s West Coast in 1913.

Conor O’Brien and his sister Margret aboard Kelpie off Ireland’s West Coast in 1913.

She was stuck fast, her skipper was single-handed, and there was enough of a scend running for the old boat to start showing signs of breaking up almost immediately. So O’Brien launched his dinghy, put everything he could into it – including the alarm clock which he blamed entirely for the incident – and headed away to come rowing out of the fog into Portpatrick’s little harbour, surrounded by almost all his worldly goods.

The Kelpie, having played her role, was soon consigned to history, for by the Autumn O’Brien’s new world-girdling Saoirse was already under construction in Baltimore. But in re-visiting the gun-running, we find that although Asgard landed her guns directly onto the pier in Howth, the 600 guns which Kelpie had brought towards Ireland were transferred in the shelter behind St Tudwal’s Island off the coast of North Wales on to Sir Thomas Myles’ Chotah.

Chotah had been volunteered by her remarkable owner to drop the remainder of the arms consignment – with himself in charge - on the beach at Kilcoole in County Wicklow, as his hefty vessel was fitted with an auxiliary engine, which it was felt would be more than helpful in beach manoeuvres.

As a further precaution, the Wicklow landing also used the services of the Nugget, a motorized fishing boat owned by the McLaughlin family of Howth. But Nugget – like the Kelpie – was recorded in image and memory. However, after the Kilcoole adventure, Chotah seems to have disappeared from sight, and no photos of her have yet been found.

Which is odd, because Sir Thomas Myles (1857-1937) was no stranger to the camera and a certain level of fame. He was a man of many talents in addition to being one of the foremost medical specialists of his generation, with a particular skill in hospital administration. He was politically active on behalf of Home Rule in his native Limerick, and in Dublin where he was subsequently based, he was a sportsman of many interests including boxing – he went three rounds with Jack Dempsey – while sailing was another interest, developing into an abiding love of cruising which he continued to the end of his long life.

Sir Thomas Myles with relatives and friends in Dublin Bay aboard Faith, one of the several large yachts he owned during a sailing career which he continued until well into his late 70s

Sir Thomas Myles with relatives and friends in Dublin Bay aboard Faith, one of the several large yachts he owned during a sailing career which he continued until well into his late 70s

For the past two years, Ireland’s sailing community has recalled this remarkable man with the annual ISA/Afloat Sailing Awards being staged in the Royal College of Surgeons on Stephens Green in Dublin, using assembly rooms which Myles was instrumental in creating. As well, he is honoured in the Sir Thomas Myles board-room in the college. But although he was a member of both the Royal Irish and Royal St George Yacht Clubs, so far as I know there are no photos of any of his several yachts – some of them very large craft – on display in either clubhouse.

It’s an intriguing absence, and there’s certainly a general interest in knowing more. One person who has taken this a step further is marine artist Brian Byrnes, who has been fascinated by the Thomas Myles story since childhood. On family holidays in Kilkee, he can remember being mesmerised by the rocky inlet of Myles Creek, and was told that like many Limerick families, the Myles family holidayed in Kilkee, and young Thomas was wont to swim in this special creek, and then swim clear across Kilkee Bay while he was at it.

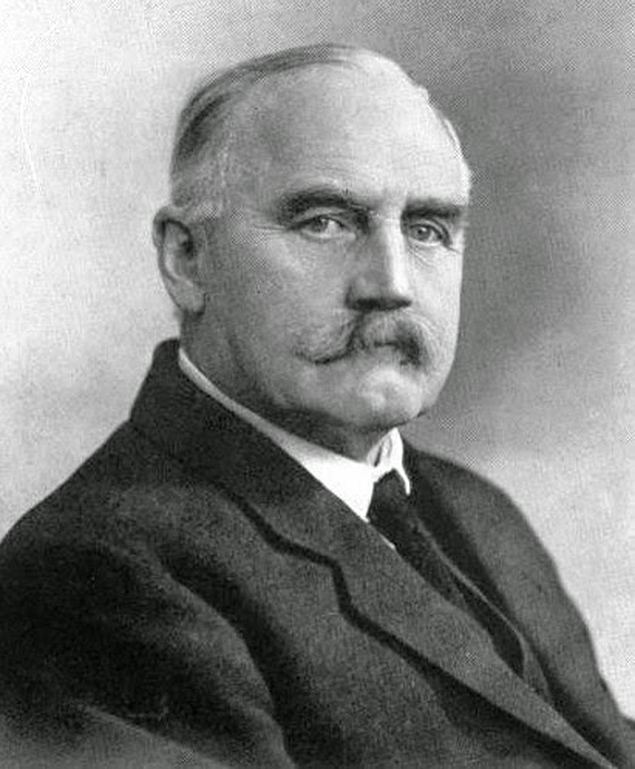

Not a man to be trifled with….Sir Thomas Myles: surgeon, sailor, boxer, swimmer, sportsman and gun-runner.

Not a man to be trifled with….Sir Thomas Myles: surgeon, sailor, boxer, swimmer, sportsman and gun-runner.

Thus this almost mythical Thomas Myles became godlike to the young Byrnes, and anything he was reported as having said was holy writ. So when the artist decided to give himself a break from the day job of painting precise illustrations of maritime scenes and specific sailing boats (in his Dublin studio he is currently producing portraits of two Olin Stephen-designed International 6 Metres), he set out to create a painting of Chotah as Thomas Myles described her.

Brixham trawlers with cutter rig. Chotah is believed to have been similar to these craft.

Brixham trawlers with cutter rig. Chotah is believed to have been similar to these craft.

In their final years as sailing vessels, the largest Brixham trawlers tended to be ketch rigged.

In their final years as sailing vessels, the largest Brixham trawlers tended to be ketch rigged.

Chotah was a yacht based on the classic cutter-rigged Brixham trawler type, 60ft long and 48 tons Thames measurement, built by S Dewdney & Sons of Brixham in 1891. She was by no means the largest or most luxurious of the yachts that Myles owned, but she suited him at a time when his medical career was at its busiest, and in due course he had her fitted with an auxiliary engine to enable him “to steam along”, as he put it himself, when time was pressing and the wind was absent.

Myles’s use of the vintage term “steam along” dated back to the days of seafaring when sailing ships were being displaced by new ships whose doughty chief engineers would describe them as “driven by steam as nature intended”. And when Brian Byrnes decided to paint a portrait of Chotah as based on the standard Brixham trawler of that size, type and era, he also did some research into how they might have been fitted with an auxiliary steam engine – in other words, how on earth did they manage to set a mainsail and have a smokestack at the same time?

Some of the bigger trawlers converted to ketch rig, which would have accommodated the smokestack immediately forward of the mizzen. But then Brian discovered that other vessels which remained cutter-rigged had come up with the idea of doing away with the mainboom, keeping the gaff permanently aloft, and brailing the loose-footed mainsail up to it in the manner of a Thames sailing barge.

Brian Byrnes suggests that Chotah may have accommodated a smokestack for her steam auxiliary engine by having a loose-footed mainsail which brailed up to the gaff boom.

Brian Byrnes suggests that Chotah may have accommodated a smokestack for her steam auxiliary engine by having a loose-footed mainsail which brailed up to the gaff boom.

This certainly solved the problem of the mainsail clearing the smokestack, and it was in line with Thomas Myles’ accounts of Chotah “steaming along”. So in visualizing what Chotah might have looked like, the artist allowed himself complete artistic licence, and created this fine study of Chotah coming through Dalkey Sound with the Muglins beyond, and the loose-footed main pulling good-oh while steam and smoke come from the stack to indicate that the auxiliary engine is ready for action as they enter Dun Laoghaire harbour.

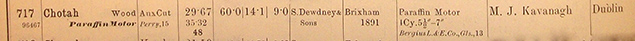

It’s an absolutely lovely idea, and all power to Brian Byrnes for visualising it. But unfortunately reality seems to have been otherwise. During all the excitement of the Asgard Gun-running Centenary in 2014, Pat Murphy (who played a key role both in making sure that Asgard has the semblance of a rig in her museum berth, and also led the movement to build a re-creation of her little dinghy) somehow found the time to do a bit of research on all the vessels involved with Erskine & Molly Childers and their friends in 1914. And in Lloyds Yacht Register of 1915, Pat found evidence that although he might have liked to think of himself as steaming along, Sir Thomas Myles actually installed a humble Bergius paraffin auxiliary engine in Chotah in 1913, and it was that little “stinkpot” which made Chotah indispensable for the Kilcoole gun-running.

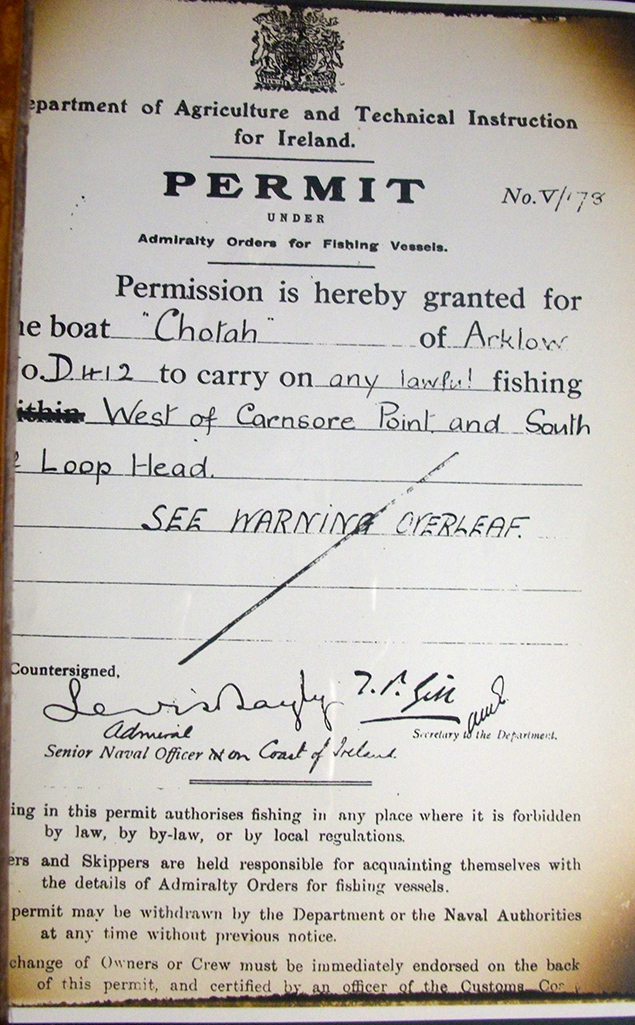

The Lloyds Yacht Register for 1915 was the last one published for four years while World War I was fought, and then in the Register for 1920 Pat found that Chotah did indeed as rumoured go to Arklow to become a fishing boat under the part ownership of Michael Kavanagh, although oddly enough he continued to register her as a yacht.

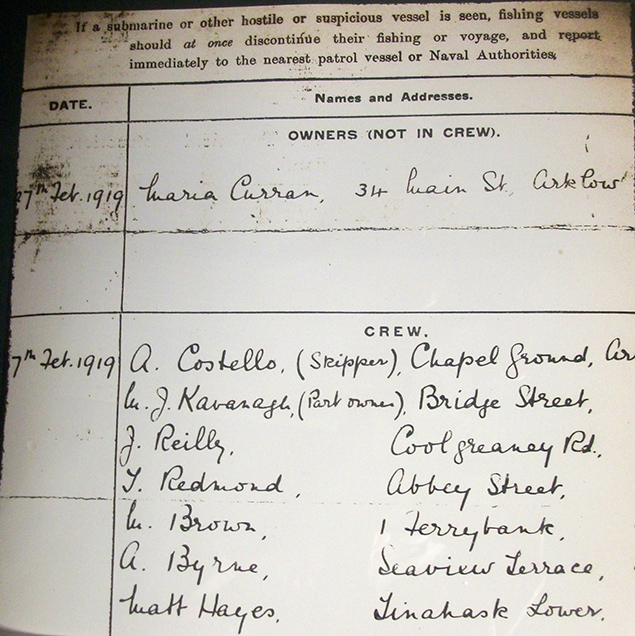

But while a visit to Arklow Maritime Museum by Pat Murphy and fellow Asgard enthusiast Wally McGuirk may have failed to find any photo of Chotah in her Arklow days, what it did find was clear evidence that she had been sold off for fishing by the end of World War I, and her Fishing Permit for 1919 is on display, together with the names of all her crew.

Who knows, but somewhere in Arklow there may be an old photo of the basin with Chotah among the fishing boats there. It would be quite a find. Meanwhile, it seems that Brian Byrnes might have to take his brush to that smokestack in order to create the more probable reality.

On the other hand, just as a postage stamp with some printing fault or without perforations is worth very much more than an unblemished one, so it could be argued that Brian’s visionary notion of Chotah with a smokestack is truly priceless. If somebody of a pedantic frame of mind wants a painting showing her as she more probably was, then it should be commissioned as a new work of art. Meanwhile, let’s hear it for the smokestack.