David Lovegrove, President of the Irish Sailing Association, steps down in a week’s time. The conclusion of his three year period in office at the up-coming ISA Annual General Meeting relieves him of what is surely the most demanding voluntary position that Irish sailing can offer. W M Nixon has been finding out more about a busy life with a remarkable record of freely-given service to our sport.

Of all Ireland’s many sports, it is sailing and boating in its numerous forms which has most suffered attrition during the economic collapse after the crazy Celtic Tiger years. Despite efforts to make boat-oriented waterborne activities as affordable as possible through shared ownerships and other club and group schemes, there’s no escaping the fact that it is quintessentially a vehicle activity. It still depends to a large extent on the continuing personal enthusiasm of private boat owners. And expenses inevitably rise exponentially as boat sizes increase.

Yet as the downturn arrived with unprecedented suddenness in 2008-09, sailing and boating groups found themselves with fleets they could no longer afford. They’d clubhouses – many of them listed historical buildings - that seemed increasing like unnecessary luxuries. Recovery was slow, if it occurred at all. In some cases it ddn’t, and the national authority, the Irish Sailing Association, was heading into financial meltdown by 2012-2013.

During the boom years, its expansion had reflected the euphoric national mood. An increasing permanent staff with a rocketing salaries and wages bill led to an unwieldy management structure which was inevitably slow to respond to the new and rapidly-changing circumstances. It was clear that some dramatic gesture was needed to show that there was going to be a complete change of the attitude and ethos of the Association’s governance.

David Lovegrove (second right) in the family garden in his own-built Fireball Simba at the age of 18, with crewman Joe McKeever on the right. His father gave him £100 to build the boat, but with careful project management, he was able to return £3 to his dad when the job was finished

David Lovegrove (second right) in the family garden in his own-built Fireball Simba at the age of 18, with crewman Joe McKeever on the right. His father gave him £100 to build the boat, but with careful project management, he was able to return £3 to his dad when the job was finished

Under the constitution of the ISA, a new President was due for election at the AGM in the spring of 2014. Normally the new incumbent would be drawn from the ranks of the existing Board members. But there was a reluctance by anyone to allow their name to go forward for what would in effect be a full-time damage-limitation job carried out on a voluntary basis.

And in any case, there was an increasing feeling that things were in such a mess that the only way to show that they were serious about real change was to persuade a respected outsider to take on this thankless task, a poisoned chalice.

In a larger sailing country, the President of the National Authority is a position of dignity and considerable importance. But in terms of our own sailing history, the ISA is of only relatively recent formation. In Ireland, with our almost incomparably long sailing history, we’re in a country where it is thought natural that the senior club should be headed by an Admiral who is treated as an equal - at the very least - by the Admiral of the Naval Service itself.

However, the President of the ISA has not been automatically accorded the dignity his position should merit, unless he or she is a person of such standing in the sailing community nationally that their natural air of authority propels them into a position of equal respect. And in times past, in dealing with the senior flag officers of the major clubs, the ISA President could sometimes feel like a relatively weak mediaeval king dealing with a group of powerful warlords, each with a treasure chest which often out-matched the monarch’s central funds.

But for the ISA, the saviour has become international competition towards Olympic level, which is basically the only form of sailing that the Irish public and Irish government departments understand. The ISA controls this, and thus it is the conduit of a source of public funding which gives it a level of independence from the wayward clubs.

Yet in the final analysis, the ISA goes back to being reliant on the clubs, for it is only through clubs that the Association is able to ensure a ready supply of talented sailors, the best of whom will enable them to tap into the honeypot of central funding for performance athletes.

So there we were in 2013 with most of the clubs severely stretched, and the ISA living way beyond its means, yet in order to get things back on an even keel and bring sailing back to life, a completely fresh President had to agree to take on this hugely demanding job.

It’s not the first time that David Lovegrove of Howth has found himself being unexpectedly propelled into a position of national and international sailing significance from what was almost an outsider position. Back in the 1960s, he was one of the pioneers – led by the great Roy Dickson of Sutton Dinghy Club – who got the Fireball class going to national success. By 1966, Lovegrove had won through to be the Fireballs’ representative in the Helmsmans Championship, raced that Autumn in Enterprises in Kinsale.

The defending champion was James Nixon of Trinity College (DUSC), and though neither of them was to win in Kinsale, Nixon liked the Lovegrove approach to racing, and got to talking with him. He was amazed to find that although Lovegrove was also a Trinity student, he had not thought to get involved with the college’s successful team racing club, as his sailing attention was absorbed with the successful Fireball Simba, which he’d built himself.

“But it’s your DUTY to try and get a place on the Trinity team!” expostulated Nixon. As James Nixon is my brother, I can well imagine the scene.

The upshot of it was that this talented outsider was brought into the heart of the Trinity team-racing fold, and became one of that lineup of college superstars who, in the late 1960s, had won just about every trophy going, in one particular year holding the Irish title, the Northern Universities title, and the British title all at once.

The Trinity heroes. The all-conquering Dublin University SC team of the late 1960s were (left to right) David Lovegrove, Johnny Ross Murphy, Vincent Wallace, Owen Delany, John Nixon, Peter Craig, and Peter Courtney

The Trinity heroes. The all-conquering Dublin University SC team of the late 1960s were (left to right) David Lovegrove, Johnny Ross Murphy, Vincent Wallace, Owen Delany, John Nixon, Peter Craig, and Peter Courtney

From that time there emerged David Lovegrove’s reputation amongst a much wider grouping than Sutton sailing and the Fireball class. He was perceived as an almost diffident steady Eddy type, capable of complete dedication and total enthusiasm when it was most needed. In the Autumn of 2013, Irish sailing administration needed it very badly indeed. Although initially Lovegrove rejected out-of-hand the idea of being parachuted abruptly into the ISA Presidency, a friend from those very special years of the late 1960s, Brian Craig - the quintessential backroom operator of Irish sailing - eventually persuaded him that he was the only man for the job, and he took it on in the Spring of 2014.

So who is he, this man who stepped into this hottest of hot seats when it was a very cold place, and all within a very short period of retiring from a demanding international career, while his own personal involvement in sailing was increasingly committed to high level Race Officer activity?

It was on Nairobi Dam in the 1950s that David Lovegrove started sailing, with International Cadets, Fireflies, and International 505s. His father was probably in charge of the track on which the old steam train is running on the far shore of the lake

It was on Nairobi Dam in the 1950s that David Lovegrove started sailing, with International Cadets, Fireflies, and International 505s. His father was probably in charge of the track on which the old steam train is running on the far shore of the lake

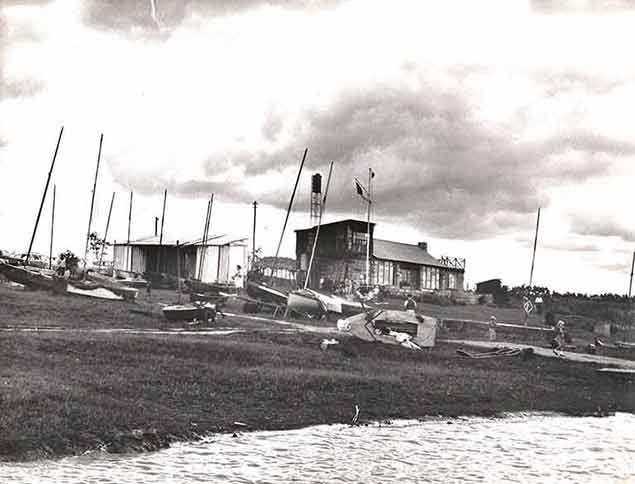

Sailing nursery. The Aqua Club on Nairobi Dam – David Lovegrove’s first sailing was with the International Cadet in the foreground, on its side for work on the mast

Sailing nursery. The Aqua Club on Nairobi Dam – David Lovegrove’s first sailing was with the International Cadet in the foreground, on its side for work on the mast

Although born in 1947 to a family living on the Sutton waterfront facing southwest into Dublin Bay, his father – a railway engineer – wasn’t into sailing, and in the early 1950s the stagnating Irish economy persuaded him to move his family to Kenya. It was there, at the age of eight or nine, that a school friend from a sailing family introduced him to the wonders of it all on nearby Nairobi Dam. He was completely hooked - “smitten” is the word he still uses today. In short order, his newfound enthusiasm took him through International Cadets, Fireflies, and on into the exalted heights of the International 505 class. But while the sailing on the lake was idyllic, the political position in Kenya was rapidly deteriorating. In 1963 the Lovegrove family returned to Ireland and the house in Sutton, and his mother, concerned at her sixteen year old son’s need to adjust to the Irish climate, bought him a classic duffle coat which he keeps for good luck to this day, though it’s now well-covered with glue and paint from his boat-building habit.

Ten years earlier, he’d been unaware of Sutton Dinghy Club, but now he went along to see what was happening, and met up with Ian Sargent who, even then, was promoting the IDRA 14 class with total single-mindedness. The class in Sutton had a boat with a girl owner, Eleanor Hazleton, who didn’t like steering. For three years through Sargent machinations, David Lovegrove helmed her boat while she crewed, and the boy just back from Kenya got drawn ever deeper into Irish sailing.

Simple spot. Sutton Dinghy Club as it was when David Lovegrove - recently returned to Ireland from Kenya - joined it in 1963.

Simple spot. Sutton Dinghy Club as it was when David Lovegrove - recently returned to Ireland from Kenya - joined it in 1963.

The development pace was being set in Sutton by the ever-enthusiastic, always-obliging Roy Dickson whose workshop was available to anyone with boat plans, and in 1965 David Lovegrove’s father provided his son (aged 18) with £100 to build a Fireball. Always one to keep meticulous records, young Lovegrove built his new Simba as economically as possible, and when the boat was ready to sail, he totalled his final figures and was able to return £3 to his dad.

Crewed by the likes of Joe McKeever, Nat Healy, and then Vincent Wallace who was to be a team-mate in the stellar Dublin University all-conquering squad, young Lovegrove found himself competing in the Fireballs in a decidedly eclectic group of all ages, abilities and backgrounds. It gave him an unrivalled overview of the Irish sailing scene at its most diverse, and provided close friendships which have lasted to this day.

Meanwhile in life ashore he graduated from Trinity, married Kate Chillingworth who more than tolerated his sailing and boat-modifying enthusiasms, and started a family. They now have two daughters, Sarah and Joanne, both of them sailors. And David himself began a distinguished career with the Industrial Development Authority, helping to build a new Ireland which was remote indeed from the stagnating place he and his parents had left in the early 1950s.

While busy with his work at home and abroad, he continued sailing as much as possible, and in the late 1970s his focus shifted across the peninsula to Howth as he reckoned the rapidly-growing Squib class there provided the ideal boat for family use while also meeting the needs of the man of the house, who was mad keen on racing. Howth was in its rapid development stage, with the new marina opening in 1982, and the Lovegroves moved up in boat size in 1983 to the newly-introduced Puppeteer 22, a boat-with-a-lid, albeit a small one. As with their Squib, the boat’s name was Snowgoose, and many a trophy she added to the list.

The Puppeteer Class at Howth. One of the most successful local classes in the harbour, the Lovegrove family have owned one of them since the class’s inauguration in 1983. Photo: W M Nixon

The Puppeteer Class at Howth. One of the most successful local classes in the harbour, the Lovegrove family have owned one of them since the class’s inauguration in 1983. Photo: W M Nixon

Howth Yacht Club in its period of greatest expansion needed calm, capable administrators and negotiators, and David Lovegrove soon found himself drawn into various committees and sub-committees. But in addition to continuing as a keen sailor, he was further developing another of his interests afloat – as a Race Officer, where he acquired international status. He was involved in running the famous Admirals Cup trials of 1987 at Howth, where the Chairman of the Selectors, Clayton Love, insisted that racing continue despite the 50 knots-plus of wind. The race team of Jock Smith and David Lovegrove obliged, even if it did mean that at one stage the Dubois 40 Jameson was all over the place waving her legs in the air, while the committee boat rounded out their day by rescuing a capsized mark boat, a Dory, which had headed skywards over a steep breaking wave, and just kept on going until she’d looped the loop.

The Dubois 40 Jameson struggling with 50-knot gusts at the Admirals Cup trials at Howth in 1987. Photo: Rick Tomlinson

The Dubois 40 Jameson struggling with 50-knot gusts at the Admirals Cup trials at Howth in 1987. Photo: Rick Tomlinson

The winds were so strong at the 1987 AC trials that a Dory heading into the waves looped the loop. David Lovegrove is at the helm of the Committee Boat now doing rescue duty. On the upturned boat is Brian Jennings, for whom David Lovegrove had built a Mirror Dinghy with which young Jennings won the Irish Mirror Nationals

The winds were so strong at the 1987 AC trials that a Dory heading into the waves looped the loop. David Lovegrove is at the helm of the Committee Boat now doing rescue duty. On the upturned boat is Brian Jennings, for whom David Lovegrove had built a Mirror Dinghy with which young Jennings won the Irish Mirror Nationals

With the new marina-side clubhouse completed in March 1987, Howth’s sailing potential had moved up several gears, and inevitably David Lovegrove’s talents were recruited towards the flag officer stream, with the powers-that-be positioning him so neatly that he was right on the starting grid to become Commodore as Howth YC’s Centenary came up over the horizon in 1995. Thus it was he and Kate who welcomed President Robinson to the Club for the Centenary Fleet Review, the highlight of a busy season in which Howth boats were achieving notable success at home and abroad.

It’s the Howth Yacht Club Centenary in 1995, and HYC Commodore David Lovegrove and his wife Kate welcome President Mary Robinson to the club. Photo courtesy HYC

It’s the Howth Yacht Club Centenary in 1995, and HYC Commodore David Lovegrove and his wife Kate welcome President Mary Robinson to the club. Photo courtesy HYC

Fleet review. With President Robinson reviewing the Howth YC Centenary Fleet from the Guardship, the marina is almost empty. Photo courtesy HYC

Fleet review. With President Robinson reviewing the Howth YC Centenary Fleet from the Guardship, the marina is almost empty. Photo courtesy HYC

While he continued as an avid race with the Puppeteer 22s – he’s a One-Design man through-and-through – he was ever ready to take on some boatwork task, and back in the day he’d built each of his daughters optimised Mirror dinghies. In fact, his workmanship was so impressive that the local GP, Damien Jennings, had asked him to build another Mirror for his son Brian, offering wads of cash. Yet all David wanted was the cost of the materials to be covered, as he found the task sufficiently rewarding in itself. But inevitably it ended up being done in the winter, and one night it was gone 9.0pm when he finally got stuck into the next task in the garage-cum-boatbuilding-shed, installing the boat’s tanks with the garage doors and windows sealed off, and the heaters going full blast.

Anyone who ever built a Mirror will recall that while most of it could be done alone, at certain stages a second pair of hands is essential, however briefly, and on that night this stage occurred at 1.30 am. There was nothing for it but to waken Kate who had been long asleep, and beg for her help. She hauled on her dressing gown, threw an old rug on the garage floor, and slithered in under the boat to provide that vital bit of back-up at the key moment, while glue dripped on her forehead.

The job done, her husband relaxed, and started smothering her with thanks in profusion. “What on earth were you thinking” he asked, “lying there on the cold floor of the garage with the glue dripping on your face?”.

“I was thinking” she said, “of Damien and Bernadine Jennings snug at home and well asleep in their warm bed”. But the boat was a winner – young Brian Jennings went on to win the Irish championship with her.

David Lovegrove took early retirement from the IDA at the age of 55, but that was only to enable him to set up an international consultancy which took him all over the world for the next dozen years, advising governments in countries as diverse as Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, Colomibia, Peru, Surinam, every country Central America and many other places in the Middle East down to Sudan.

At home between these extensive travels, he became ever more immersed in the world of race management, and over the years built up a team around him, a team now functioning so smoothly like a well-oiled machine that they can simply transfer the entire squad to whatever location needs race management services. But given the choice, they prefer to operate from Howth’s own larger Committee Boat Star Point, which has been cleverly modified to David Lovegrove and his team’s suggestions, coupled with the suggestions of other top Howth race officers like Derek Bothwell, to provide a formidable race management platform.

Star Point, the larger of HYC’s two Committee Boats, may not be the most handsome vessel afloat, but with clever modifications suggested by David Lovegrove and other experienced race officers, she is one of the most effective committee boats in the country.

Star Point, the larger of HYC’s two Committee Boats, may not be the most handsome vessel afloat, but with clever modifications suggested by David Lovegrove and other experienced race officers, she is one of the most effective committee boats in the country.

The Lovegrove Race Team on Star Point at last year’s ICRA Nationals at Howth are (left to right) David Lovegrove with his notorious 1963 duffle coast, Algy Pearson, Rupert Jeffares, Suzanne Cruise, Judith Malcolm, Kate Lovegrove, and Harry Gallagher

The Lovegrove Race Team on Star Point at last year’s ICRA Nationals at Howth are (left to right) David Lovegrove with his notorious 1963 duffle coast, Algy Pearson, Rupert Jeffares, Suzanne Cruise, Judith Malcolm, Kate Lovegrove, and Harry Gallagher

As to the day job with its extensive travelling, he’d made a deal with himself that when the homeward journey became more exciting than the outward journey, then he’d jack it in, and that stage started to arrive four years ago. But he’d barely settled in to his new more relaxed situation when the ISA came calling, and for the past three years life has been very hectic indeed.

The ISA has had to be slimmed down, shedding projects like the J/80 Sailfleet flotilla, and he went strongly with the idea that a Strategic Review should be undertaken, run by key people like Brian Craig and former President Neil Murphy.

That review came down firmly in favour of re-emphasising the role of clubs in the ISA support structure. Though it didn’t meet with total approval throughout the sailing community, particularly among those who run commercial sailing schools, at least a marker could be put down, and work could begin on improving relations with every area of sailing, for things had come to such a sorry pass that various specialist groupings were at each other’s throats, and also frequently into loudly attacking the ISA when they felt so inclined.

With his patient ready-to-listen attitude, and his willingness to travel in pursuit of opinions, David Lovegrove was the right man for the long slow progress of peace-making and creative negotiation, which will continue. He insisted that the Board meet monthly, and that it move its meeting place around the country in order to give every area a sense of direct involvement and promote Try Sailing projects.

All this was time consuming and decidedly unspectacular, but it was very necessary, and even as this sometimes dull but essential work continued, things were happening to give Irish sailing a fair wind. In 2014, Ireland re-took the Commodore’s Cup under the inspired captaincy of Anthony O’Leary, and as he was at the time also the ISA All-Ireland Champion, the stardust rubbed off on everyone.

Despite the lingering effects of the setbacks of the recession, people were getting out and winning major events in boats which were no longer in the first flush of youth, but were all the better sailed for that, and almost invariably it would be noticed that the President of the ISA, in addition to his many duties, was as usual working aboard a Committee Boat making sure that races were run with punctilious precision.

Gradually a greater level of civility returned, and the mod was good as 2016 came upon us to provide the greatest Irish sailing season ever, starting with a bronze medal in the Youth Worlds for Dougie Elmes and Colin O’Sullivan, going on with success for everyday Irish sailors at home and abroad, then too we’d a fabulous Volvo Round Ireland Race from Wicklow, there was a brilliant innovation with the Beaufort Cup series in Cork, an international dinghy regatta to top all others with the Laser Radial Worlds in Dublin Bay when our own Ewan MacMahon won Silver, and then an excellent all round showing in the Rio Olympics topped by Annalise Murphy winning the Silver Medal.

No-one deserved this overall success more than the patient and dutiful David Lovegrove. Typically, though, he wasn’t there on the beach in Rio when Annalise Murphy brought Ireland and the world to a halt with her cliff-hanger win of the Silver Medal. On the contrary, he was in Plymouth in southwest England, fulfilling a longterm commitment to be Race Officer at the J/24 Europeans.

That’s the way it is with David Lovegrove. Duty will always come before celebration. But apart from steadying the ship at a time when the ISA and the Irish sailing community were going through a very rough time, he has brought an extra dignity to the role of ISA President. He may be small in stature, but David Lovegrove is a big man in his approach to the problems of life. He quietly withstood some seriously vindictive yet totally undeserved personal attacks when he first took over the post of President. For a while, things were very unpleasant. But he has stood his ground and has listened with courtesy to all points of view.

Thanks to his approach, the position of President of the ISA is now beginning to receive the respect it deserves as a special position, regardless of the personal situations which may arise from time to time. For that alone, Irish sailing should be very grateful to David Lovegrove. But we’ll continue to be grateful to him for many years yet, for as soon as the new season swings into action, he’ll be there on the starting line with a season’s programme of race organisation which would be beyond many men half his age.

Throghout all this, his wife Kate has been the rock on whch has been able to rely. Late in the Spring of last year, she realised it was all in danger of becoming overwhelming, so she whisked him away for five weeks clear of everything to do with Irish and international sailing. She did this with the trip of a lifetime to China on the Trans-Siberian Express, which does indeed get across Siberia, but “express” is stretching it bit. However, the President returned to Ireland completely refreshed to see out one marvellous sailing season which he very richly deserved.

With his three year ISA Presidency completed in a week’s time, David Lovergore is looking forward to a busy season as a Race Officer at home and overseas – and he might even get to do some racing himself on his Puppeteer 22 Snowgoose. Photo: Judith Malcolm

With his three year ISA Presidency completed in a week’s time, David Lovergore is looking forward to a busy season as a Race Officer at home and overseas – and he might even get to do some racing himself on his Puppeteer 22 Snowgoose. Photo: Judith Malcolm