The functioning of the Commissioners of Irish Lights is within a matrix in partnership with the Northern Lighthouse Board in Scotland and the Isle of Man, and Trinity House in England and Wales. They co-operate actively through a grouping known as the General Lighthouse Authorities, which in turn operates with larger supra-national inter-linking associations and authorities that extend a global reach. Their shared mission is to provide the world’s seaways and shipping with a uniform and effective system of navigational aids and regulatory systems.

Yet each constituent authority such as the Commissioners of Irish Lights (CIL, Coimisineiri Soilse na hEireann) has its own strong identity, for each in turn has emerged – usually over many centuries - from uniquely local conditions and particular historical circumstances. Globalisation has inevitably spread a strong element of uniformity, and the accelerating capacity and capability of computers is resulting in massive changes both in the way the Lighthouse Authorities function, and the number of staff they require to fulfill their vital role. But as W M Nixon discovered during an informative visit this week to Irish Lights headquarters in Dun Laoghaire - a visit which included a highly instructive tour of their familiar service vessel Granuaile - there is definitely something reassuringly Irish about the Commissioners of Irish Lights.

Although Irish Lights provide, maintain, develop and monitor a wide variety of aids to navigation all round our long, complex and often challenging coastline, for most people in Ireland it is the remarkable selection of 81 distinctive lighthouses which still provide the perception of what Irish Lights is all about.

As you’d expect, it is our most maritime-minded county of Cork which has the greatest number of these uniquely attractive and purposeful buildings – 16 in all – while next in line is Donegal with 11, reflecting the fact that while Cork has a long and complex coastline on the busier southwestern corner of Ireland. Donegal presents many navigational challenges for all vessels approaching the northwest corner.

Ireland being the size it is, most of us will be familiar with the presence of at last one lighthouse, while many of us will have several favourites. But although there has been a marked opening-up of the activities of Irish Lights in recent years, with the Twelve Great Lighthouses scheme providing holiday accommodation at some very special venues in what were formerly the houses of lighthouse keepers and their families, most of us still harbour at least part of the mindset which thinks that there should be something mysterious and perhaps a little sacred about the lighthouse service and its workings.

Certainly in the case of Ireland, the sacred aspect has historical resonance. For although the Commissioners of Irish Lights were officially established in 1786 and headquartered in Dublin, the earliest record of an Irish lighthouse service is in Wexford at Hook Head at the east side of the entrance to Waterford Estuary, where a monk called Dubhan started tending a lighted beacon in the Fifth Century, and his successors maintained it more or less continuously until Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland in 1641. It all started here. Dawn at Hook Head, County Wexford, where a warning light for mariners was first shown in the 5th Century

It all started here. Dawn at Hook Head, County Wexford, where a warning light for mariners was first shown in the 5th Century

The provision of lights for navigation inevitably followed the main lines of shipping routes and sea trade, and in the late medieval period and on through Tudor and Stuart times, this put an emphasis on providing services for all ports between Youghal and Drogheda, places which came under the influence of the mighty (and often rather ruthless) city-port of Bristol.

In time, despite its shallow entrance, Dublin emerged as the main Irish port. But it was a slow long process through a number of grandly-named - or indeed oddly-named - bodies, their roles sometimes over-lapping before 1786, when Irish Lights was set up (Motto: In Salutem Omnium: For the Safety of All) to rationalize many local organisations, and provide an all-Ireland service which radiates out from Dublin to this day.

In fact, its focus is now totally through Dun Laoghaire, where Irish Lights have had their shore headquarters since 2008 in a striking modern award-winning circular building designed by star architects Scott Tallon Walker, and located on site together with the CIL workshops, research and development departments and the extensive “buoy yard” in a busy harbourside complex where their service vessel, the 2,625 ton Granuaile, can come alongside for direct access two hours either side of high water.

Here’s where it is now. Irish Lights HQ in Dun Laoghaire

Here’s where it is now. Irish Lights HQ in Dun Laoghaire

In times past, the organisaton seemed to function in more leisurely styles in keeping with the pace of each era, with the main offices located in a fine terrace of Georgian buildings in Pembroke Street in the heart of fashionable Dublin 2, while what was at one stage a flotilla of service vessels if all were gathered together at the Dublin quays. But that was a rare enough event, as usually they were away on their allocated duties on specific parts of the coast.

Yet nowadays, even though the pace and location is more intensely focused, with personnel cut back as computers and automation take over many aspects of a service which was formerly labour-intensive, there still is a certain attractive air of mystery about the way in which Irish Lights carry out their activities.

To a considerable extent these days, this is because staff numbers are minimized, and Chief Executive Yvonne Shields has to oversee an extremely efficient and focused organisation whose functioning is always under scrutiny. Although other lighthouse authorities get most if not all of their income from shipping dues, Irish circumstances are such that Irish Lights relies on a government subvention to top up its funding, and when public money is directly involved, you’re working in a special environment.

Yet even in the past when lighthouses were still being built as a matter of course – the Fastnet was completed as recently as 1904, the “new” light on Inishtrahull in 1958, and the light on the extended East Pier at Howth in 1981 – the fact of there being an element of public works in CIL’s activity did little to make their activities more public. They were seen as a very specialised service, there were many recognized “light service families”, and generally it was felt that the less the public knew about their well-trained and ethos-laden activities, the better.

But now, as its core staff get smaller but even busier, Irish Lights is letting the light in, so to speak. This week a party of three dozen or so of us from the Small Craft Group of the Royal Institute of Navigation, the Irish Cruising Club, and the Dublin Bay Old Gaffers Association spent an informative day with CIL, and came away hugely impressed with the dedication and expertise of the entire operation.

The interior of the award-winning Irish Lights HQ is elegant and functional. Photo: W M Nixon

The interior of the award-winning Irish Lights HQ is elegant and functional. Photo: W M Nixon

If you’re wondering at the eclectic makeup if those attending, it’s because we’d to close in on Wednesday September 6th when the Granuaile would be in port making her 28-day complete crew changeover. The people at CIL felt that information time in the offices, research units, workshops and buoy yard would only make sense if afterwards we saw the ship in detail to give us an insight into the means whereby their products and services are conveyed to locations all round the coast of Ireland. Thus as Paul Bryans and Darryl Hughes run the RIN Small Craft Group for all that they spend substantial chunks of their time in Ireland, and both are members of the ICC while Darryl is active in the DBOGA, we soon had the required numbers of people who were seriously interested in what CIL does, and how it does it.

For me it was of special interest, as my last close encounter with Irish Lights had been Before the Revolution. Irish Lights is always working hard to be in the vanguard of technology, yet until the early 1980s this was at a fairly leisurely pace. But then electronics and computers with remote monitoring began to sweep through. The manning of lighthouses was gradually discontinued, lightships and their crews were replaced by large equipment-filled buoys, and the entire economic environment changed.

Yet the dedicated and generally cheerful attitude of Irish Lights staff prevailed even as their numbers were inevitably diminishing. Thanks to a well-selected board of Commissioners and high staffing standards, the personnel management was sound, and CIL was set on a course which seemed eventually and inevitably to lead to a very focused operation based entirely in Dun Laoghaire, and operating with just one extremely busy ship.

But the most visible aspects of this transformation were still well in the future when I shipped as a guest of one of the Commissioners aboard the Granuaile’s predecessor, the yacht-like 1970-built 2000-ton vessel also known as Granuaile which, despite her relatively recent construction, really was a last relic of ould dacency.

The 1970-built Granuaile was the second Irish Lights vessel to carry the name. With her tiny workspace right forward and enormous allocation of luxurious accommodation, she was about as different as possible from the current ship

The 1970-built Granuaile was the second Irish Lights vessel to carry the name. With her tiny workspace right forward and enormous allocation of luxurious accommodation, she was about as different as possible from the current ship

The Commissioners kept a close eye on the workings of their cherished organisation, and every summer they had a working cruise round Ireland aboard the Granuaile inspecting the lights and other aids to navigation under their charge. In order to accommodate them, the ship had emerged as about 80% filled with the engine room, crews quarters, bridge space, officers cabins and rather luxurious accommodation for the Commissioners, but barely 20% was given over to an inconveniently small working space on the foredeck right under the bridge served by a small derrick, while around it were various workshops located in the part of the ship most prone to violent motion if she was at sea.

The section of the Irish Lights circuit I did in 1986 was from Bangor on Belfast Lough round to Killybegs, and while everyone worked extremely hard during days which started early, each night in some agreeable anchorage – for the local knowledge of Irish Lights crews is unrivalled - the Commissioners dined on board like the Lords of Creation, and if they went ashore it was to visit one of the choicest hostelries on the coast, while from the shore were brought out the most interesting and informed of local characters.

That stage of the cruise concluded with an on-board black tie dinner in Killybegs hosted by the Captain, Paddy Mangan from Kerry, who looked splendid in his full dress uniform, with CIL’s head inspector Dennis Gray in particularly fine form. As to the work done during the cruise, it was considerable, varied, and thorough, and all the time I was impressed by the technical expertise in some specific area of CIL activity which each Commissioner seemed to have made his speciality. In fact, some of them sometimes had little enough to say until their area of expertise came up the agenda, when they’d leap to life with information and advice which was world class.

But while the ship was lovely, she was already an anachronism, totally out of kilter with the new area of utility and functionality, and in due course Dennis Gray identified a service vessel for sale in the North Sea which was so useful for a temporary replacement for the very out-dated Granuaile that the delighted Commissioners called her Gray Seal.

The temporary replacement. Gray Seal in Dun Laoghaire – she provided useful lessons for designing the new Granuaile in 2000

The temporary replacement. Gray Seal in Dun Laoghaire – she provided useful lessons for designing the new Granuaile in 2000

Gray Seal was in turn only in use while a pioneering replacement ship was planned to be built from new, a total purpose-functioned vessel which Irish Lights would commission to be the prototype for light services the world over, and this was the new Granuaile, built in 2000, aboard which we were to spend the afternoon.

It says everything about the quality of the presentation given by Captain Robert McCabe, Director of Operations and Navigation Services, backed up by his Strategic Support provider Barbara Fogarty with further input by Technology and Development Services director John Burke, that the morning in the boardroom, offices and workshops was ever bit as interesting as the afternoon on the ship.

Light Commissioners the world over provide an increasing number of services despite the fact that some amateur sailors might reckon things like lighthouses to be superfluous thanks to modern electronics navigation aids (a navaid is aboard ship, an aid to navigation is not). But time and again it has been demonstrated this isn’t so, and you certainly wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of some legal dispute trying to show that aids to navigation are superfluous. So the way ahead for Lights Commissioners is to make the running of their lighthouses as economical as possible, and increase their input into all areas of seafaring.

Captain Robert McCabe, Barbara Fogarty and John Burke of Irish Lights. Photo: W M Nixon

Captain Robert McCabe, Barbara Fogarty and John Burke of Irish Lights. Photo: W M Nixon

Ireland has been an ideal testing ground for developing ways of saving money in running a lighthouse, as we have such a variety of them to work with. It seems that one of the most expensive lighthouses in the world used to be the Bull Rock off County Kerry northwest of Dursey Island. It was just remote enough to be a special challenge, it often called for helicopters, and in the days when keepers lived on it, the money just ran out the door.

So Irish Lights started their own line of researching in developing economical LED (Light-emitting Diode) lights for use in lighthouses, and the one they fitted to the Bull Rock was a first of its type. It has been operating successfully since 2012, and now the main work project is replacing the famous light on Mew Island with a LED setup, while transferring the entire old-style Mew Island light equipment to the Titanic Centre in Belfast.

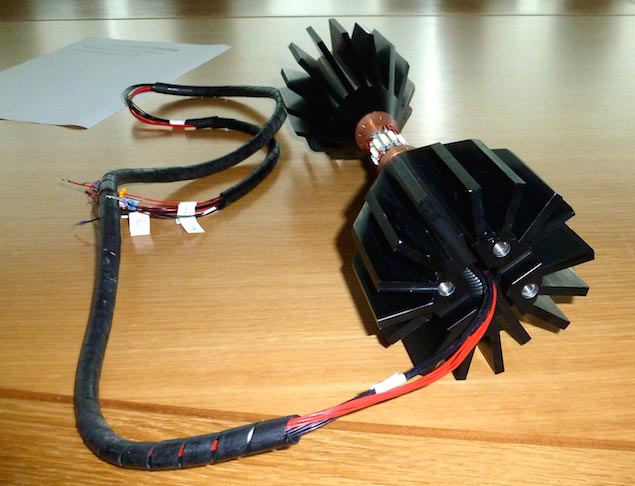

A LED light developed by Irish Lights. The LED light is the narrow bit in the middle – just visible are the Light Emitting Diodes. The big black fins on either side are the heatsinks, whose function is to take all the heat away as quickly as possible from the electronics and LEDs. Photo: W M Nixon

A LED light developed by Irish Lights. The LED light is the narrow bit in the middle – just visible are the Light Emitting Diodes. The big black fins on either side are the heatsinks, whose function is to take all the heat away as quickly as possible from the electronics and LEDs. Photo: W M Nixon

The Mew Island light being restored in Dun Laoghaire. It has been replaced by one of Irish Light’s own LEDs, and when the restoration is complete, this old light unit will go on display at the Titanic Centre in Belfast. Photo: W M Nixon

The Mew Island light being restored in Dun Laoghaire. It has been replaced by one of Irish Light’s own LEDs, and when the restoration is complete, this old light unit will go on display at the Titanic Centre in Belfast. Photo: W M Nixon

This interaction with local communities is not new – the Maritime Museum in Dun Laoghaire has the impressive old Kish optic as a feature display – but now it is taken for granted, and Irish Lights, as a visible presence with many skills and a remarkable multi-purpose ship, inevitably finds itself at the centre of many maritime operations such as last weekend’s emergency exercise off Dunmore East, while they also played a special role in the search mission after the RS 116 tragedy at Black Rock in Mayo.

Looking to the future, they see interaction with other agencies as naturally increasing, so it may well that far in the future – for everyone’s now planning to 2030 and beyond - some recreational sailors will find the passing Irish Lights vessel taking a friendly interest in them, for the harsh fact is that nearly 50% of fatalities at sea come from the recreational sector.

Preoccupied with such thoughts, it was a welcome change to tour the workshops which vary from specialist micro-work benches to a fully fitted high-ceiling place – it has been used for public gatherings – which is also maybe the last wooden boat-building premises on the entire Dublin City and County waterfront. It seems that for their ocean-operating workboats which get launched by davits from the side of the ship with the crew already on board, the Irish Lights seamen still prefer to use a wooden boat of a well-proven type.

The Irish Lights workshop in Dun Laoghaire is one of the very few places left in Dublin where it is still possible to see traditional boat-building under way in a waterfront environment. Photo: W M Nixon

The Irish Lights workshop in Dun Laoghaire is one of the very few places left in Dublin where it is still possible to see traditional boat-building under way in a waterfront environment. Photo: W M Nixon

One of Irish Lights’ wooden boats in the davits on the Granuaile. When the boat is being sent off on some task, the crew simply step aboard with the boat like this, and are then lowered onto the sea. Photo: W M Nixon

One of Irish Lights’ wooden boats in the davits on the Granuaile. When the boat is being sent off on some task, the crew simply step aboard with the boat like this, and are then lowered onto the sea. Photo: W M Nixon

Outside was the extensive buoy-yard which had the complete range, everything from new buoys testing plastic construction through solar-powered smart buoys to a rusty old veteran which had somehow come across the Atlantic from Nova Scotia, and we all were lucky that no-one sailed into it during its slow progress, for it would have given as good as it got.

Don’t they want it back? This buoy drifted across the Atlantic from Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotian buoyage authority are probably too embarrassed by the failure of their mooring to ask for it back. Photo: W M Nixon

Don’t they want it back? This buoy drifted across the Atlantic from Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotian buoyage authority are probably too embarrassed by the failure of their mooring to ask for it back. Photo: W M Nixon “One of the buoys that were buoys when I was a boy….” Paul Bryans with the South Briggs Buoy from Belfast Lough. Photo: W M Nixon

“One of the buoys that were buoys when I was a boy….” Paul Bryans with the South Briggs Buoy from Belfast Lough. Photo: W M Nixon

As Paul Bryans and I started our sailing on Belfast Lough, we were delighted to find in the buoy cluster one of the buoys that were buoys when we were boys, the South Briggs which marks a reef between the lough and Donaghadee Sound. Suitably elated by one of the worst jokes of the year, we made our way in a condition of information overload for a spot of welcome lunch at the Royal Irish Yacht Club and then headed east for the Carlisle Pier where the Granuaile was one very busy ship.

She certainly earns her keep. She works her way round the coast of Ireland more or less every 28 days, and is then back in Dun Laoghaire for one day of complete crew change and a detailed and thorough handover. You’d think that a crew in the middle of this would have more than enough to do, but we were graciously welcomed, and with the party divided in two, were able to get to know a fantastic ship.

Everything about the new Granuaile is expressive of the times in which we live. Functionality and internationalism is everything. She was built in Romania and finished in the Netherlands in 2000. And at every crucial stage of her construction, the Irish Lights specialists were invited to be present to make their input into the layout of this new type of vessel.

A mighty workspace. Granuaile’s generous afterdeck and huge derrick. Photo: W M Nixon

A mighty workspace. Granuaile’s generous afterdeck and huge derrick. Photo: W M Nixon

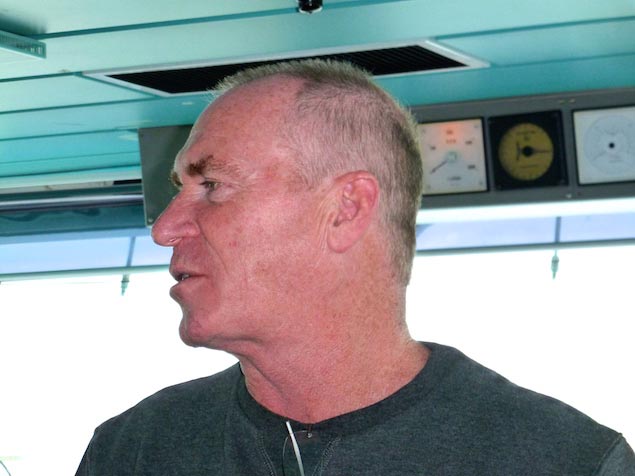

But some things don’t change, and Irish Lights is always strengthened by its sense of family involvement and tradition. Thus one of the key people in deciding how the unbelievably spacious bridge should be laid out to make best use of its 360 degrees control sphere was Declan Gray, the son of Dennis Gray with whom I’d gone along the coast on Donegal on the old Granuaile back in the previous millennium. And when we went up to the fantastic bridge, there to welcome us was Captain Declan Gray, very much dressed down as he was in the final go-everywhere stages of taking over the ship for the next 28 days, yet with us to talk to, it was clear that his enthusiasm for the new Granuaile burns as brightly as it did when she was brand new 17 years ago.

Captain Declan Gray – as enthusiastic today about the Granuaile as he was 17 years ago when she was new. Photo: W M Nixon

Captain Declan Gray – as enthusiastic today about the Granuaile as he was 17 years ago when she was new. Photo: W M Nixon

As the photos clearly show, everything is focused on work getting done, and keeping an eye on it wherever it may be happening. Everything is devoted to keeping control of the ship and what happens aboard her, regardless of the sea conditions.

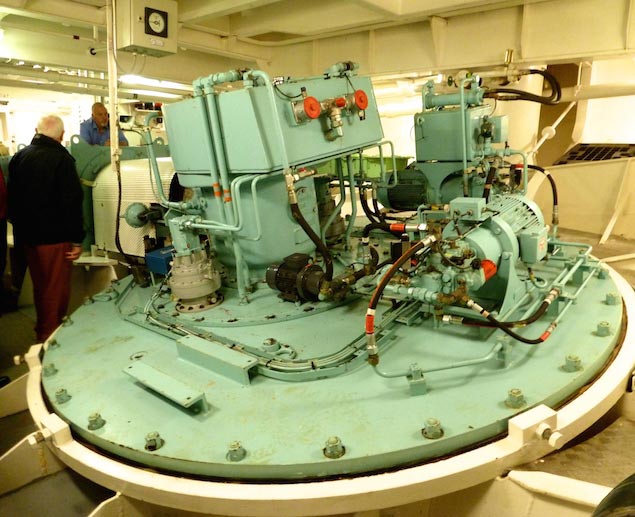

Her engines, which are completely backed up, provide 4,000hp of diesel electric power, transmitted through two thrusters, one on each quarter which, together with a bow thruster, can either be operated independently or operated together – manually or by computer – to position the boat precisely.

Deep down in the stern of the ship, the starboard thruster is slightly reminiscent of a giant saildrive. It obviates the need for rudders. Photo: W M Nixon

Deep down in the stern of the ship, the starboard thruster is slightly reminiscent of a giant saildrive. It obviates the need for rudders. Photo: W M Nixon

The only change that might be made to the concept of 2000 is that the bow thruster be replaced with two independent thrusters, but as it is they’ve pinpoint control with none of your old-fashioned rudder nonsense – those thrusters on the quarters look after all steering.

As for a steering wheel – forget it. The passage control centre at the forward end of the bridge is all special thrust controllers and joysticks, as is the position command control panel at the starboard aft side of the bridge. Declan Gray can work it all with confidence and a real flourish, and the result is 2,600 tons of ship which can be placed on a one cent piece.

The steering position….there’s no wheel, just thruster controls. Photo: W M Nixon

The steering position….there’s no wheel, just thruster controls. Photo: W M Nixon

On the starboard side aft in the spacious bridge, the position control panel has everything you need including computer input to position the vessel exactly. Photo: W M Nixon

On the starboard side aft in the spacious bridge, the position control panel has everything you need including computer input to position the vessel exactly. Photo: W M Nixon

As for accommodation, she’s certainly comfortable, for regular crew and specialist staff can be on board for 28 days at a stretch, but there’s definitely not the applied opulence of the old ship. Everything is built around work requirements with usefully low freeboard around a huge working deck space aft, a king size derrick, and fully-equipped workshops below in the position of least motion.

Thus the new Granuaile can do the work which in the old days required two or three ships, and she can do it without requiring costly service yards in distant parts of the country, as modern heavy trucks means that a large item can be moved by road from Dun Laoghaire as and when she needs it, and delivered to any quayside where she has her own gear to lift it aboard.

It’s curious that this hive of working activity should be at the heart of what is increasingly seen as the recreational harbour of Dun Laoghaire. And the people at Irish lights are frank in discussing how some things in an otherwise orderly move out from Dublin have not gone as they expected. For instance, when the new main building was being planned in 2002-2008, they underestimated just how much the expansion in computer capabilities would reduce their need for office space. But it ultimately wasn’t a major problem. They decided that their needs could be fully met by using just the upper storeys, and letting out the ground floor offices to outside users.

Happily, the situation is now stabilisised, and Irish Lights, while continuing in its traditional functions, has successfully expanded into other related income-generating areas. But under-pinning everything, there is still that instinctive sense of duty and loyalty to a remarkable organization.

A classic Irish Lights story tells of James Kavanagh, the Wicklow stonemason who built the Fastnet Rock. Although increasingly ill, he insisted on staying on the rock into June 1903 in order to see the last enormous stone into place on the top course, number 89. He collapsed as it went perfectly into place, and was taken ashore in a semi-coma, having personally set every stone on the lighthouse.

James Kavanagh died in July 1903, and he has become a byword for the spirit of Irish Lights. Currently, Kevin Whitney, one of the Chief Officers on the Granuaile, is teaching classes in a Naval Reserve course in Haulbowline during his periods ashore between the 28-day spells on the ship. The 2017-2018 intake into these courses is called the James Kavanagh Year.

The 1898-built Howth 17 Leila (Roddy Cooper) rounding the Fastnet Rock in July 2003, a hundred after James Kavanagh laid the final stone to complete the great lighthouse. Photo: W M Nixon

The 1898-built Howth 17 Leila (Roddy Cooper) rounding the Fastnet Rock in July 2003, a hundred after James Kavanagh laid the final stone to complete the great lighthouse. Photo: W M Nixon