Work began this week at Oldcourt near Baltimore in West Cork on reconstructing Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse. One of the most remarkable sailing vessels in Irish and world maritime history, the 42ft Saoirse is unique in many ways. W M Nixon gives some of the background to a complex story.

The early 1920s in Ireland are generally remembered as a time of extreme turmoil, with a War of Independence, the establishment of the Irish Free State with Northern Ireland partitioned, and a Civil War which was followed by a restless period as the fledgling State developed its new identity.

Yet in this uneasy time of frequent disruption, in Baltimore in West Cork a special boat, a proper little ship, was built in 1922 to become an ocean voyager which provided a vision of a more peaceful time for a world still only slowly recovering from the horrors of World War I in 1914-1918.

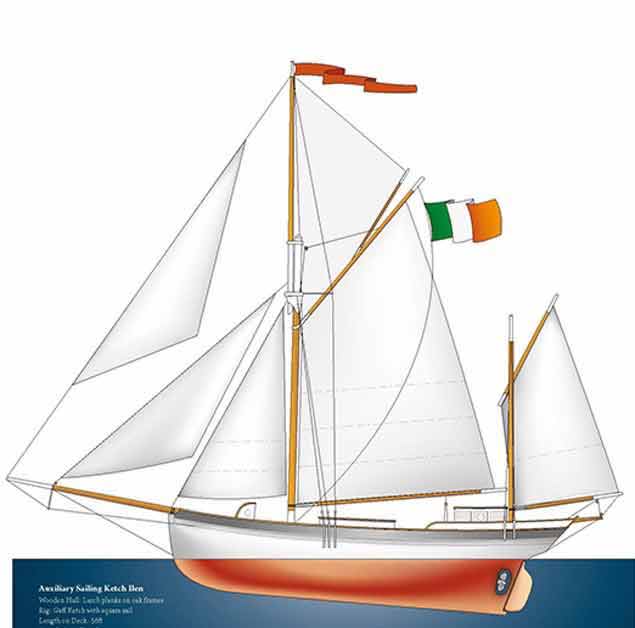

This unique sailing ship was also a maritime inspiration for the new Ireland, uncertain of itself in an uncertain world. For this was Conor O’Brien’s characterful 42ft ketch Saoirse, which he designed himself, and with which - between 1923 and 1925 – he pioneered the round the world route south of the Great Capes, an ocean voyaging “first” which was forever written into world sailing history.

The scale of Conor O’Brien’s achievement at the time is difficult for us to grasp today, when we are aware that the Great Southern Ocean, which runs unhindered round the globe and regularly generates extreme storms, can indeed be navigated by relatively small craft, albeit with the strongest of construction, the best of equipment, and experienced crews.

But in the early 1920s, it had a completely fearsome reputation, and rounding Cape Horn was a venture undertaken only by the most capable and usually very large sailing ships, or the most powerful steamers. So when the little Saoirse rounded the Horn from New Zealand in the last of the daylight on Tuesday December 2nd 1924, it was a pioneering achievement for everything which has come since, including the Golden Globe, the Whitbread Race, and the Volvo Ocean Race.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

In Ireland, the greatness of what Conor O’Brien and Saoirse had done was recognized at the time, and his departure from Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923 was well celebrated and reported in the Dublin newspapers. Accounts of some aspects of the voyage then appeared in the press in Ireland during its progress, and Saoirse was welcomed back to Dun Laoghaire afloat by Dublin Bay Sailing Club cancelling its racing for the day to provide an escorting fleet, and ashore by a crowd of at least ten thousand, followed by a ceremonial parade into the city with the day concluding with a gala dinner.

After that, O’Brien was busy with writing the story of the voyage for what was to be a popular book, Across Three Oceans, and seeing through the fulfillment of a contract for the construction of a larger version of Saoirse to be the inter-islands communications vessel for the Falkland Islands, for the islanders there had been much impressed by the little ship’s sea-keeping power when she came into port with Cape Horn successfully astern.

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

The 56ft ketch Ilen was the result of this, and O’Brien – crewed by Cape Clear men Con and Denis Cadogan – sailed her out to the Falklands in 1926 from his home port of Foynes in the Shannon Estuary. For although his boats were built in Baltimore by Tom Moynihan and his team at the boatyard attached to the Fisheries School, the O’Brien ancestral lands were along the south shore of the Shannon Estuary, while his first steps afloat were at Foynes, though he also learned sailing at Derrynane in West Kerry where the family took summer holidays. But from 1914 onwards, as the effects of Land League and other factors diminished the family estate, Foynes Island was both his home and his home port in Ireland.

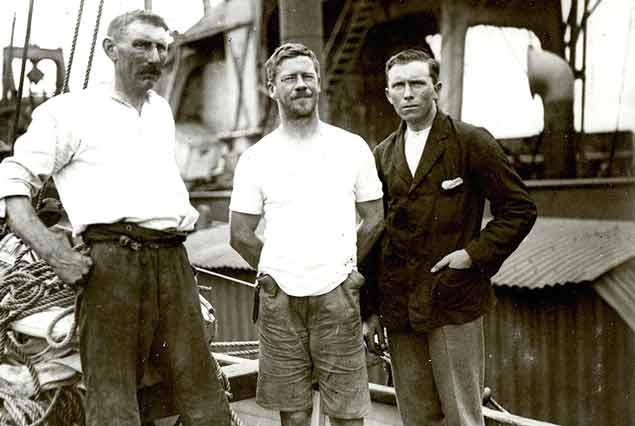

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

However, with the publication of Across Three Oceans and the completion of the Ilen contract, his diminishing income was temporarily boosted, and 1927 was celebrated with the ketch-rigged Saoirse being given a rather spectacular new rig which, despite the same masts being retained, made her look like something of a small brigantine, and with this O’Brien set out to do the Fastnet Race.

This meant he spent some time in Cowes beforehand, where he was much feted, with the legendary designer Uffa Fox taking off Saoirse’s lines. For although she was rightly described as “a bluff-bowed little boat”, by the standards of the day she had achieved some formidable 24-hour runs during her circumnavigation, and Uffa Fox was determined to see if he could find some special secret to her shape to explain the high average speeds.

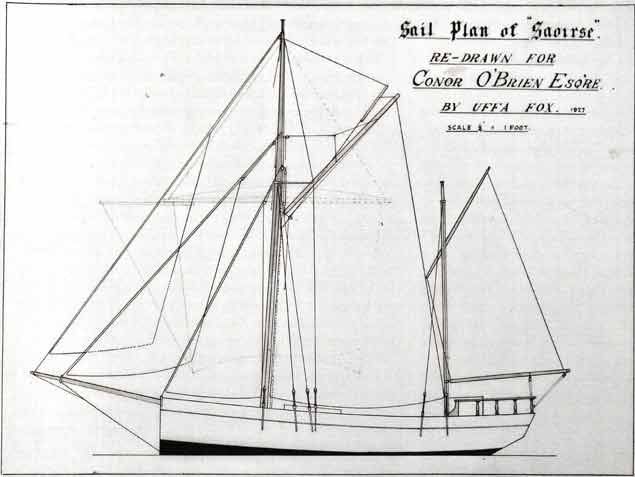

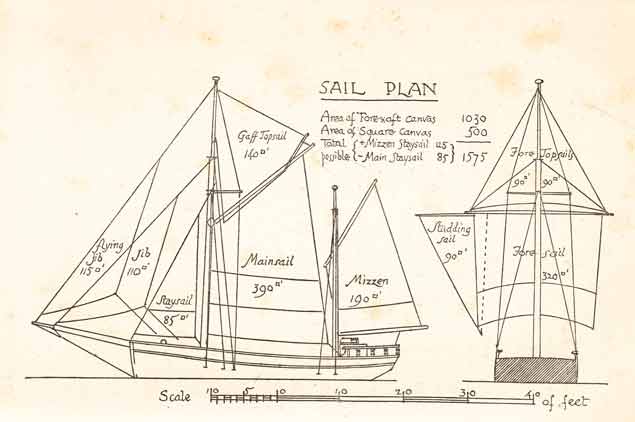

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

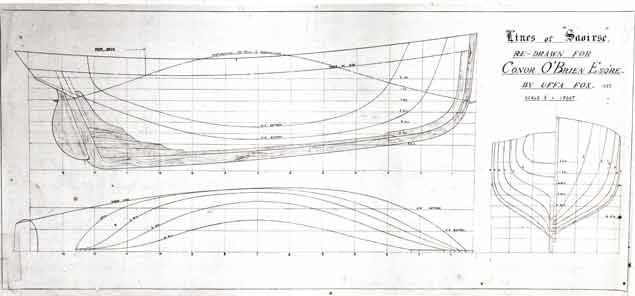

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

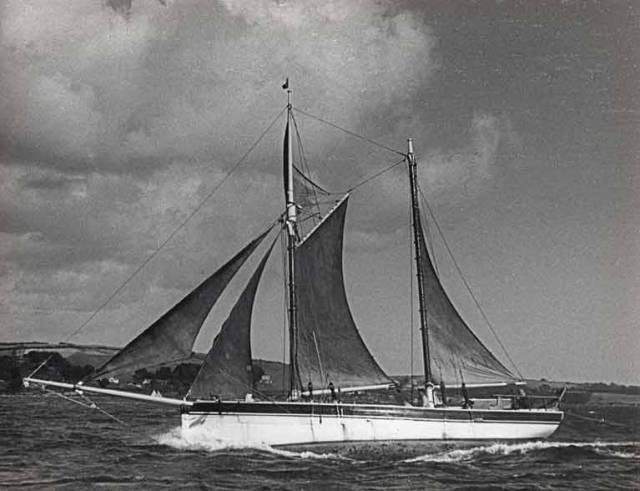

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

But the secret was Conor O’Brien himself. Although the Fastnet Race was dismal for Saoirse as it involved much windward work, off the wind with his nerves of steel he was able to drive his peculiar little ship well beyond her theoretical limit. Yet he almost always brought her to port in one piece, and his judgment of what was possible was renowned.

From this you might expect a stern steady silent type, but Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) was a man of many talents and a mass of contradictions. Short-tempered, sometimes voluble to excess, he expected too much of crews who were sometimes casually recruited, and in all he may have had as many as 17 different people crewing with him during Saoirse’s circumnavigation.

Away from his sailing, his life sometimes seemed aimless. Reared largely in England though holidaying in family properties in Ireland in the summer, following some changes of direction he finally qualified as an architect, and after 1903 he lived for some years in Dublin. Mountaineering was his main outdoor activity, but soon he was further into sailing, and by 1910 he’d bought the hefty cutter Kelpie which he modified for cruising with conversion to a ketch.

Another interest was support of Home Rule for Ireland, and in July 1914, Kelpie joined Erskine Childers’ Asgard in going to collect the arms for the Irish Volunteers from a rendezvous at the Ruytigen Lightship off the Belgian coast. While Asgard’s consignment of Mauser rifles was spectacularly landed in broad daylight in Howth on July 26th, the Kelpie’s cargo was brought ashore at night a few days later at Kilcoole in County Wicklow, having been trans-shipped to the auxiliary yacht Chotah, owned by another distinguished sailing man with direct Limerick connections, the surgeon Sir Thomas Myles.

Within a very few days, the entire scene changed with the outbreak of the Great War, and most of the leading gun-runners were to serve with the British forces. Despite his Home Rule enthusiasm, O’Brien had since 1910 been a member of the Royal Naval Reserve, which had given him useful training for his growing involvement in sailing. Between 1914 and 1918, it provided him with sometimes uneven war experience, for his temperament was much more suited to small unit action than anything involving significant numbers in some sort of organised form.

Post war, he returned to an Ireland which since the 1916 Easter Rising was moving inexorably towards independence and inevitably towards partition. When a unofficial Independent Provisional Government was set up in 1919 in a sort of parallel universe functioning effectively in opposition to British rule from Dublin castle, he offered his services to it with the Kelpie, and was a seaborn Fisheries Inspector for this alternative administation on the West Coast in the summer of 1920.

The situation was confused, to say the least, and in 1921 he went off cruising to Scotland single-handed, with some mountaineering planned in Skye. Returning alone through the North Channel and slowly beating to windward at night, he slept through the ringing of an alarm clock, and the heavy Kelpie came ashore in the foggy dark, well stuck on rocks near Portpatrick on the Scottish coast, and slowly but inevitably became a total loss.

O’Brien appeared out of the morning mist into Portpatrick Harbour, rowing in his little dinghy with all that remained of his worldly possessions about him, for he had sold his house in Dublin, and all he had for home was the use of a family cottage on Foynes Island.

As he recovered both there and with family in Dublin from his ordeal – typically blaming the alarm clock – he started finalizing the designs of an ocean-going voyager. For although he had no personal experience of long sea voyages under sail in a small yacht, he had long wished to do so, but had known the Kelpie was far from ideal for such ventures. What he wanted was a boat of simple ketch rig capable of setting proper square sails for long runs in the Trade Winds.

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.

His acquaintance with the skills of Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore had come about when Kelpie had been damaged during severe weather off the Mayo coast during his season in 1920 as a Fisheries Inspector. The repairs at Baltimore satisfied even the pernickety O’Brien, so as the winter of 1921-22 progressed, negotiations led to the beginning of the construction of a 40ft ketch of a virtually unique design.

She had been kept down to 40ft overall to fit into O’Brien’s very limited budget, but Tom Moynihan felt that would make her so dumpy as to be ugly, a poor advertisement for the boatbuilders of Baltimore. So he and his men quietly increased her overall length to 42ft by the addition of a very fore-shortened counter which redeemed the situation, and O’Brien was later to admit that, in this at least, Tom Moynihan had saved him from himself – his original version of Saoirse would have been something of an ugly duckling.

Nevertheless the new ketch was a boat of very primitive type. When we consider that just three years later, William Fife was to design the extremely elegant 70ft Bermudan-rigged Hallowe’en which went on to take line honours in the 1926 Fastnet Race, by superficial comparison Saoirse seems like a mighty backward leap of at least a hundred years in design development.

The 70ft Fife-designed cutter Hallowe’en, line honous winner in the 1926 Fastnet Race, at the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire. Her design appeared just three years after Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse. Photo: W M Nixon

The 70ft Fife-designed cutter Hallowe’en, line honous winner in the 1926 Fastnet Race, at the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire. Her design appeared just three years after Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet which boat would you rather be on board for long periods at sea? Like virtually all yachts of her era, Hallowe’en’s galley was well forward in a position of maximum movement in any seaway, and while her wide saloon was stylishly comfortable in port, at sea it was too spacious. On deck, the only comfort is for two or three in the small cockpit.

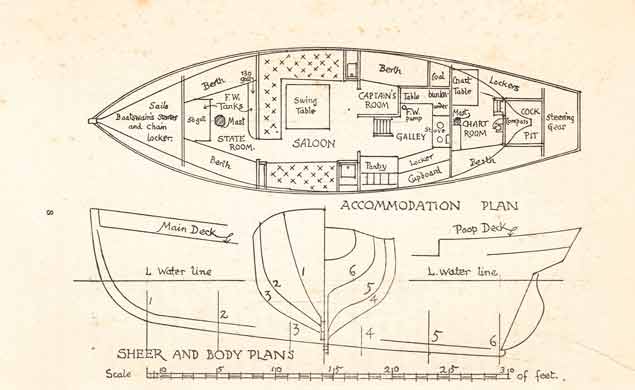

By contrast, with the accommodation layout of Saoirse, Conor O’Brien deployed his full architectural enthusiasm for the Arts & Crafts concepts of simplicity, comfort and functionality. He placed the homely galley well aft, he created a saloon which would have felt appropriate in a cosy cottage yet worked extremely well in port or at sea, and in all he created a comfortable little ship of suprisingly good performance which sailed in harmony and provided accommodation that fitted around you like a much-loved jacket.

Saoirse’s accommodation layout as drawn by Conor O’Brien was positively homely. In placing the galley well aft, he was way ahead of his time

Saoirse’s accommodation layout as drawn by Conor O’Brien was positively homely. In placing the galley well aft, he was way ahead of his time

This reassuring homeliness of Saoirse was well proven in the years following her great voyage. In 1928 Conor O’Brien – then aged 48 – was tamed a little, and certainly slightly domesticated, when he married Kitty Clausen, an English artist from a noted creative family of Danish descent. Her family had links to Cornwall, to which O’Brien was already attracted as he found the increasingly conservative and repressive mood of the new Irish Free State to be very much at variance with the liberal Home Rule ideals he’d supported in 1914 and again in 1920 when he’d sailed as a fisheries inspector.

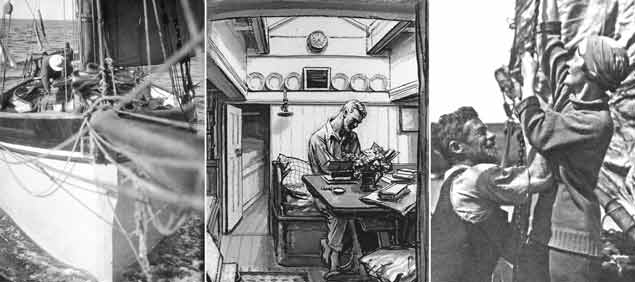

Thus the southwest coast of Cornwall became their home area, with Saoirse based at St Mawes on the east side of Falmouth Harbour. But soon they were on their way, cruising to the Mediterranean, where they overwintered with a base at Ibiza – very different from what it is today – while Conor wrote, and Kitty sketched and painted.

Married life aboard Saoirse for Conor OBrien and Kitty Clausen. On left, the little ship makes her easy way across the Mediterranean, at centre Conor enjoys the comfort of the homely saloon, and at right the newly-weds hoist sail. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Married life aboard Saoirse for Conor OBrien and Kitty Clausen. On left, the little ship makes her easy way across the Mediterranean, at centre Conor enjoys the comfort of the homely saloon, and at right the newly-weds hoist sail. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

The success of Across Three Oceans and the magnitude of his voyaging achievement had established him as an authority on seamanship, but none of his subsequent books on this and other topics were the same runaway success as that first masterpiece.

Nevertheless he enjoyed reasonable success with accounts of their Mediterranean cruises – one was to the Greek isles – charmingly illustrated by Kitty. But this idyllic phase of their life together was all too brief, by 1934 it was clear that Kitty was unwell, they sailed back to Cornwall, and in 1936 she died at St Mawes, it is believed of leukaemia.

For a year or so Conor O’Brien was something of a lost soul, at one stage living aboard Saoirse while she was laid up in the boatyard at Falmouth. But he’d found another outlet for his writing talents with adventure boys for books, and in all he had five of these published, while also producing another four books on seamanship and yacht equipment.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 had provided another opportunity. He renewed links with the Royal Naval Reserve and joined the Small Vessels Pool, positioning small craft for the Navy, and filling the role so well that in 1943 he found himself having a fine old time in New York – whose brazen new architecture he adored - involved in the shoreside running of the organisation which made preparations for naval crews to deliver American-provided craft across the Atlantic to the main war zone.

Saoirse while owned by the Ruck family in the 1950s. To simplify sailing, they have fitted a boom to the previousy boomless mainsail.

Saoirse while owned by the Ruck family in the 1950s. To simplify sailing, they have fitted a boom to the previousy boomless mainsail.

But meanwhile he had sold Saoirse in 1941 to an English owner Vincent Ruck, who was to base her between Chichester Harbour in Sussex and Falmouth Harbour in Cornwall, and over the years along that coastline of the south of England, Saoirse was to receive her quota of quiet but approving recognition as the unusual little ship which had pioneered the global route south of the great Capes.

At the end of World War 2 in 1945 and now aged 65, Conor O’Brien returned to Foynes Island for the rest of his days. He kept himself busy building small boats, and sometimes he lived almost like a hermit, but at other times he’d emerge and socialize. He’d been made an Honorary Member of the Irish Cruising Club, and attended some of its dinners. And as he’d kept himself notably fit - if the mood took him in summer, he’d swim with his clothes in a bundle on his head across to Foynes village and stand in the bar there, the water still dripping from him, downing pints of Guinness porter and exchanging banter with the locals.

He died on the island in 1952, and was buried beside his parents at Loghill Church along the mainland County Limerick coast. Saoirse meanwhile remained a much-cherished member of the Ruck family through several generations until the 1970s, when a new owner brought her first to Ireland in 1973, and then went on to Iceland.

Dun Laoghaire in pre-marina days in 1973, and a summee roll coming in from the northeast. Saoirse – on her way to Iceland – is making her first visit to the port since 1925.

Dun Laoghaire in pre-marina days in 1973, and a summee roll coming in from the northeast. Saoirse – on her way to Iceland – is making her first visit to the port since 1925.

Subsequently she took the increasingly popular tradewind route to the Caribbean where she cruised among the islands for several years. But in unsettled weather with hurricanes about in 1979, she came ashore on Negril Beach in Jamaica. At the time it was reported that she was virtually a total loss, but a subsequent visit in recent years to Negril by Gary MacMahon of Limerick – the Conor O’Brien enthusiast par excellence - has resulted in enough artefacts and constructional items from Saoirse being recovered to make a re-build – albeit in a very complete way – a possible project, with enough of the spirit of the ship emerging to be able to state that Saoirse’s soul lives on.

But by the time these items were retrieved from Negril, as any regular reader of Afloat.ie will well know, Gary MacMahon was already well down the long route towards the re-building of Saoirse, but by a somewhat different route. In 1997 he organized the return from the Falkland Islands of the recently de-commissioned Ilen with the simple hope to restoring her to a seaworthy state with all sorts of sailing functions in mind.

Eventually this became the Ilen Project, with the Ilen Boat-Building School as a reconised training organization with proper fully-equipped premises in Limerick, while the hull of Ilen herself came under the care of Liam Hegarty at his boatyard at Oldcourt near Baltimore. For although the original boatyard on the waterfront in Baltimore where Saoirse and Ilen were built in the 1920s had gone into decline, these days Baltimore is a bustling breezy focus of West Cork sailing, one of Ireland’s truly pace-setting sailing centres, and waterfront property has become much too expensive to accommodate a workaday boatbuilding yard.

Men with a mission - Liam Hegarty and Gary MacMahon at an early stage of Ilen’s restoration

Men with a mission - Liam Hegarty and Gary MacMahon at an early stage of Ilen’s restoration

There were considerable leaps of faith involved in working towards fulfilling the many and varied potentials of all the strands of the Ilen Project, but throughout it Gary and his team have been given the inspirational support of Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey, a personal tower of moral support in trying to achieve objectives some of which are tangible, yet others seem vague in the extreme.

But somehow or other, as the 21st Century settled in, proper work got under way on the restoration of Ilen. Resources have been stretched now and again, and it has taken time, but that’s no harm in that, for now it is one of the best-known ongoing boat restoration projects in the world, almost a matter of pilgrimage.

Meanwhile, however, Gary MacMahon and Liam Hegarty shared the view that the restoration of Ilen would only make sense if, with the experience it provided, they then went on ahead with a new project - the re-building of Saoirse. This was long a vague aspiration, but it became more real after Gary visited Negril Beach, got to know the fascinating community there, and returned with some bits and pieces which provided such a sense of Saoirse that at the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival in 2015, he and Liam found themselves in complete agreement that somehow or other, Saoirse would sail again.

Ilen (top) as she is this week after the restoration and (bottom) as she was at her launching day in 1926. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Ilen (top) as she is this week after the restoration and (bottom) as she was at her launching day in 1926. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Their faith was so total, and supported of course by Brother Anthony, that they started ordering timber in order to have secured a properly seasoned stock by the time work on the Ilen had been completed. But it was all a matter of faith until September 2016, when Fred Kinmonth came into the ancient building – it has several names, in the yard they simply call it “The Top Shed” – where Ilen was being restored. With traditional boat-building under way, it is a place of unique serenity, and the entire scene spoke to Fred Kinmonth in a special way.

Ilen (top) immediateoy before the restoration job began, and as she is now (bottom).

Ilen (top) immediateoy before the restoration job began, and as she is now (bottom).

He’s of a high-powered professional family with cherished links to West Cork – as long ago as 1966, he was cruising from Union Hall to Valentia in the family’s Tyrrell-designed-and-built sloop Sinloo. But while most Kinmonths have gone into medicine, Fred went into corporate law, and he has had a stellar career in Hong Kong and right across the Far East.

He is very much into sailing in Hong Kong and is personally linked to a series of successful boats called Mandrake (the current Mandrake III is designed in Ireland, a Mark Mills 41), while he’s also a longtime member of the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club and will be among those involved when Hong Kong welcomes the Volvo Ocean Race fleet in a few days time.

Fred Kinmonth’s Mark Mills-designed Mandrake III.

Fred Kinmonth’s Mark Mills-designed Mandrake III.

He enjoys life at the sharp end, indeed he thrives on it. But if he feels his batteries need re-charged, he puts in time in his spiritual home of West Cork. It was in this quietly thoughtful frame of mind in September 2016 that he looked into the top shed at Oldcourt and inhaled that Ilen restoration atmosphere. By the time he was returning to Hong Kong, it had been decided that Saoirse would be re-built for Fred Kinmonth, and the worked started this week.

All of which goes some way to explain why, as the rest of us wound down towards Christmas except for those heroes gearing up for the Rolex Sydney Hobart Race, down Baltimore way there was a special buzz of activity at Oldcourt around Ilen. The shipwrights’ work had been finished, the deck and houses had been sealed, most future work in joinery would be inside the hull, so it was time to move and vacate the shed for work to begin on the re-build of Saoirse.

The result is that in the depths of winter, we have had an inspiring glimpse in daylight of the transformation which has been worked on Ilen. Not only is it something which provides great expectations of what the re-built Saoirse will look and feel like, but it is very encouraging to continue progress towards Ilen’s new role as a Marine Learning Environment, a sailing schoolroom which will bring the message to schools and communities.

Ilen as she will look when she undertakes her new role as a Marine Learning Environment.

Ilen as she will look when she undertakes her new role as a Marine Learning Environment.

As for the future of Saoirse, this morning it is enough to know that the re-build is happening, but for the moment it is behind closed doors. You’ll note that as soon as Ilen was out of the shed, the great doorway in the gable end through which she had exited was closed off. Setting up to re-build Saoirse properly to a contract time is a serious business, and Liam Hegarty and his team have deserved to be left in peace during this key week.

The work moves on. Ilen is out of the shed, while inside the preliminaries for the re-build of Saoirse are under way. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The work moves on. Ilen is out of the shed, while inside the preliminaries for the re-build of Saoirse are under way. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The significance of Saoirse and her re-build contributes in unexpected ways to an awareness and maybe an understanding of our island’s complex past. The first major recognition that Conor O’Brien and Saoirse achieved was the award of the Royal Cruising Club’s Challenge Cup – the world’s senior cruising award – in 1923 while the voyage was under way. He received it again in 1924, and in 1925.

The RCC was at the very heart of the British maritime establishment. Yet despite his known gun-running voyage, the RCC had admitted O’Brien as a member in 1919. That may seem to stretch tolerance. But even more bizarre is the fact that O’Brien was proposed for membership by Frank Gilliland, a member from the north coast of Ireland, and seconded by Erskine Childers, who had joined the RCC when he started working in England in 1895.

However, by the time Saoirse departed on her voyage in June 1923, Frank Gilliland had since 1921 been Commander Frank Gilliland, Aide de Camp to the Governor of the newly-established Northern Ireland. And Erskine Childers, having come out in armed opposition to the treaty establishing the Irish Free State and the partition of Northern Ireland, had in November 1922 been executed by a firing squad of the Government of the new Irish Free State.

Through all this extraordinary turmoil and mixing of allegiances, Conor O’Brien and the Saoirse sailed on with their exceptional voyage. It was the great cruising authority Claud Worth, the adjudicator of the RCC awards, who best put Saoirse’s achievement into perspective, and explains why the work which started this week in Oldcourt is so important. Worth commented:

“Anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds of from 150 to 170 miles a day, as well as the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered.”

Amen to that.