Displaying items by tag: The Mercy

All Sailors Will Enjoy 'The Mercy' Sailing Movie, Says Pete Hogan

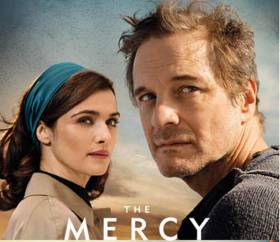

Dublin artist and round–the–world solo sailor Pete Hogan reviews The Mercy, the sailing movie starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz that is to be released in Ireland on Friday.

I was invited to the premier of this movie in the Lighthouse cinema in Dublin.

Many sailors will be familiar with the famous case of Donald Crowhurst, the tragic participant in the original Golden Globe race organised by The Sunday Times in 1968 and which Robin Knox Johnston won and thereby made his name.

Crowhurst, having first faked his progress in the race, is generally accepted to have killed himself by jumping overboard. It is a story which refuses to go away having inspired several books, documentaries, plays, poetry and now a reasonably big budget movie. Almost like the Flying Dutchman, the search for Franklin or the tale of Ulysses it has seeped into the lore of the sea.

The movie, starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz is a well-constructed affair. The nautical detail is good and includes the construction of an accurate replica of the 40’ tri he used in the race. It’s a lot better than many depictions of nautical matters by Hollywood. The movie follows closely the accepted narrative described in the original book by Tomlinson and Hall published in 1970. (The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst). There is little doubt as to the facts of the tragedy. Crowhurst purposely and pointedly left all his writings and charts for others to find - like a lengthy, gruesome suicide note.

The period detail is well done except for the corny London Boat show. It well illustrates the difference between yottin then and now. The hack journalist who promotes Crowhurst almost steals the show. Crowhurst comes across as a model, well adjusted, family man with a beautiful wife and three adorable cute children. Consequently it is less easy to explain how it all went so horribly wrong. Colin Firth makes a good attempt at portraying the mental disintegration of the lone sailor as pressure mounts and failure becomes more apparently inevitable. The boat looks appropriately shambolic and weathers well as the voyage progresses. Firth looks a bit too handsome towards the end rather than the demented tragic figure he must have been. When he hacks at his hair with a nautical knife he looks as if he has just visited Peter Mark.

Calm beautiful wife Rachel Weisz, does most to explain what went wrong. As she slams the door on the baying pack of media reporters, she declares ‘ You are all to blame, every one of you. You pushed him overboard’.

Happily we are spared the actual sight of Crowhurst’s end. Instead we follow into the depths his chronometer which he is believed to have clutched as he jumped off the stern onto the astral plane. This is not really a date movie but it is a brave one in that there was never ever going to be a happy ending.

This is a movie which all sailors will enjoy, especially those who lived through those pioneering heady days of the early OSTAR races and the Sunday Times Golden Globe race of 1968.

Postcript

At the premiere reception I was introduced to Gregor McGuckin who intends to take part in this year’s Golden Globe Race which is being held to commemorate the original one in which Crowhurst took part 50 years ago. Like Donald Crowhurst, Gregor obviously has a dream. But he seems much better grounded, balanced and prepared. I wish him good luck.