Displaying items by tag: CharlieGibbs Fracture Zone

#MarineScience - A multinational team of ocean exploration experts returned to Galway on World Ocean Day (Friday 8 June) after spending the last few weeks exploring and mapping the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

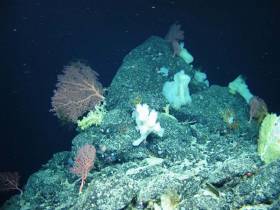

Using the robotic mini-sub ROV Holland I, the TOSCA (Tectonic Spreading and the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone) research team led by Dr Aggie Georgiopoulou of UCD collected “spectacular” film footage of sponge gardens.

In another first for deep-sea exploration, the marine science team on board the RV Celtic Explorer also found more than 70 skate eggs in a nursery some 2,000 metres below the surface.

“Up to 150 rock and sediment samples amounting to roughly 200kg along with 86 hours of video footage and over 10,000 square kilometres of the zone were also mapped, which is almost the size of Co Galway and Co Mayo together,” Dr Georgiopoulou said.

The Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone was mapped for the first time in 2015 on the RV Celtic Explorer as one of the key projects launched by the Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance, following the signing of the Galway Statement on Atlantic Ocean Cooperation between Canada, the EU and the US in May 2013.

“The high resolution data produced by Ireland’s INFOMAR programme in 2015, that revealed spectacular landscape with 4,000m-high mounds rising from the seabed to 600m below the sea surface — taller than Carrauntoohil, Ireland’s highest mountain — has been instrumental in our continued research over the last month,” Dr Georgiopoulou said.

The tectonic spreading at the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone consists of two huge parallel cracks in the crust of the Atlantic Ocean running between Ireland and Newfoundland, and is the longest-lived fracture zone in the Atlantic. It is the most prominent feature interrupting and offsetting the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

“What we have found at the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone surpassed all of our expectations,” Dr Georgiopoulou added. “Exploring three mountain areas, 500-1,000m-high scarps were discovered that have been produced by catastrophic rock avalanches, with giant boulder fields spilling into the fractures.

“Although these fracture zones are similar to the San Andreas fault in the western US and the North Anatolian fault in Turkey and Greece, with large earthquakes taking place there regularly, this is the first time there has been a dedicated geological study in the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone area.”

The TOSCA expedition involved 13 scientists from nine institutions and five different countries including Ireland, the UK, Germany, Canada and Greece.

Experts in seabed mapping, marine geology, oceanography and marine biology, each team will return to their respective Institutes to analyse all the data and work out how the mountains were formed, when and how the rock avalanches take place and how the geology affects the local habitat for marine wildlife.

Marine Institute chief executive Dr Peter Heffernan congratulated the team on their recent discoveries, stating that deep ocean expeditions cannot be taken for granted as we need to better understand the features that make up the ocean seabed.

“With the ocean affecting climate change, global population and seafood demand, we need to map our seabed to define favourable habitats for fishing, key sites for conservation, and safe navigation for shipping.

“The expedition supported by AORA also reflects the value and essential role of international partnerships, particularly with achieving the shared goals of the Galway Statement on Atlantic Ocean Cooperation 2013, which include our ongoing cooperation on ocean science and observation in the Atlantic Ocean,” Dr Heffernan said.