Displaying items by tag: Michael Murphy

Fastnet ’79: A Personal Recollection Of A Terrible Night From Skipper & Crew Of ‘Flicka’

Unseasonable gales in August have little meaning for those who experienced a terrible night that month in 1979, on the third day of that year’s Fastnet Race, as the skipper and crew of Flicka recall.

The morning after the hurricane hit, it was the lead story around the world. For a small group of Schull Harbour Sailing Club members, it was just a lucky escape.

In Schull that afternoon, fellow sailors and newsmen armed with cameras and seasick pills were going to watch the Fastnet Race frontrunners round the rock.

Michael Murphy — our skipper — and wife Derval, together with Mick Barnett, Steve Cone and the Collins girls were keen to go.

Frank Boland had offered them the use of his 36ft heavy displacement motor cruiser Flicka, and suggested that the two older members of his family, Mary and John, would come along. They headed for sea with a picnic, a bottle of grog for the crew — and a warning to be careful from harbour master Jimmy Reilly.

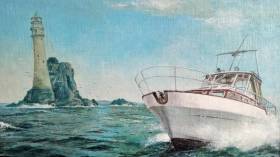

As Flicka nosed into the bay, the other boats were returning. Past Long Island, the swell deepened and the boat bounced to the Fastnet Rock. A feast was consumed on board, and as the cruiser hung around, head to wind off the lighthouse, dusk descended, with the onset of heavy rain and an ever increasing wind. In hindsight it was fortunate there was no marine radio on board, as to the east the horror of the night was beginning.

Many years later, while attending a book launch for The Lightkeeper, author Gerald Butler confirmed that he was on duty on the Fastnet that night and was trying to contact Flicka on the VHF, and eventually when he lost sight of her navigation lights he called Baltimore lifeboat, which immediately launched, but was then diverted to the Irish yacht, Ken Rohan’s Regardless which was in serious danger, having lost her steering off the Staggs.

In hindsight it was fortunate there was no marine radio on board, as to the east the horror of the night was beginning

The mystery of the boat described in his book was all the more intriguing when he discovered that the owner, Frank Boland, was one of the Commissioners of Irish Lights who had overall responsibility for the operation of the Fastnet.

Having turned for home, the full force of the storm hit — together with the realisation of the vessel’s unsuitability for the weather, with the following sea in danger of swamping the boat.

The sing-song provided a little comfort, while all eyes peered through the darkness as the nearer to Schull they motored, the more serious the situation became.

In the harbour, the wind was beyond gale force and appeared cyclonic in direction, hitting the hull from all angles. The raindrops were like thimbles flying upwards into a night that was as black as a witch’s hat. Shapes whirled in the water and lights faded in and out as the screen wipers thwacked.

Through prisms of water, Steve Cone on the bow pointed out the lights of a yacht battling its way up Long Island Sound, which subsequently turned out to be Ted Crosbie, who hugged the island shore for shelter all night. Steve’s face, lit by the bow navigation lights that matched his green oilskins, made him look like the Incredible Hulk.

With Schull pier underwater and a chaotic scene developing for the yachts lining the pier wall, it was decided to try for Flicka’s moorings. Here, Mary Boland played her ace card, managing to locate the mooring buoys. Mick Barnett and Steve managed to hook it at the first attempt, but were unable to hold on when struck by a particularly powerful gust, losing the only boathook on board. A quick search located a hooked-on boarding ladder with which Steve, lying over the bow, managed to secure the mooring, while Mick Barnett held onto his legs for dear life.

Shapes whirled in the water and lights faded in and out as the screen wipers thwacked

For Flicka’s crew, the danger was increasing. Disembarkation was to be a nightmare. Spouse was separated from spouse, sibling from sibling; if the worst happened, no family would endure a double tragedy.

Boarding the rubber dinghy was like riding a panicking porpoise and every yard travelled shipped a gallon of water. Three seemingly endless journeys landed everyone back to the pier, where the rafted yachts were splintering together while one leg of Peter Jay’s catamaran lay like a beached whale on the head of the pier.

The last to abandon Flicka was Michael Murphy, with Mick Barnett helming the dinghy. On shore, everyone tried to track them in the impenetrable darkness. Lamps were waved back and forth and names called … no sign. The only noise above the wind was the sound of children crying on the rafted yachts.

A horror began to insinuate itself into the minds of the watchers. As their senses verged on the possibility of loss, familiar voices suddenly boomed from the darkness. The little outboard engine had finally given up the ghost and the dinghy had been driven into the shingle beach in the Acres. The short walk, the hugs and laughter brought blessed relief.

The wind dropped off gradually about 4am and as the early dawn rose, both sailors and fisherman met in the metallic light to witness the havoc, only then to learn the fate of those who had encountered the demon in the night.

Patrick O’Reilly has also shared his memories of that fateful night in August 1979:

I was a 10-year-old with my late father, Barry O’Reilly — ex-Dragon sailor and ex-Tritsch-Trasch of Howth — as well as Dr Maurice O’Keeffe, Arabella O’Keeffe and Morgan Sheehy, all of Kinsale, when we left Schull Harbour on August 13th, 1979. We were on Flor O’Dowd’s beautiful 35ft ketch, with Maurice O’Keeffe at the helm.

All day, the sea state at the Fastnet was oily and sloppy. Sitting around at the Fastnet for the day caused almost all of us sea sickness which, as I remember, was fully cured by Campbell’s tomato soup and white sliced pan from O’Dowd’s bakery in Kinsale.

We saw both Ted Turner’s Tenacious and Bob Bell’s Condor round the Fastnet. My 10-year-old self definitely got a triumphal wave from Turner, the ‘mouth of the south’.

I remember well the change in weather around dusk. We surfed the following sea to the mouth of Schull Harbour. We must have got in to the harbour earlier than Flicka as we did not have the same screaming wind that they had and got ashore without incident.

That night we stayed in the East End Hotel. The hotel had the VHF wired to a tannoy, which broascast the drama of Ted Crosbie (was he sailing a Sadlier?) in Long Island Sound and indeed that of others. It was both real and surreal at the same time...