Displaying items by tag: Kearney

The Sailing Legacy of John Breslin Kearney

#irishmaritimehistory – It was a life which would have been remarkable by any standards, in any place, at any time. But in the Dublin of its era, this was a life of astonishing achievement against all the odds, in a rigidly structured society made even more conservative by a time of global unrest and national upheaval.

John Breslin Kearney (1879-1967) was born of a longshore family in the heart of Ringsend in Dublin, the eldest of four sons in a small house in Thorncastle Street. The crowded old houses backed onto the foreshore along the River Dodder in a relationship with the muddy inlet which was so intimate that at times of exceptional tidal surges, any ground floor rooms were at risk of flooding.

But at four of the houses, it enabled the back yards to be extended to become the boatyards of Foley, Murphy, Kearney and Smith. Other houses on Thorncastle Street provided space for riverside sail lofts, marine blacksmith workshops, traditional ropeworks, and all the other long-established specialist trades which served the needs of fishing boats, and the small vessels - rowed and sailed - with which the hobblers raced out into Dublin Bay and beyond to provide pilotage services for incoming ships. And increasingly, as Dublin acquired a growing middle class with the burgeoning wealth of the long Victorian era, the little boatyards along the Dodder also looked after the needs of the boats of the new breed of recreational summer sailors.

The young John Kearney was particularly interested in this aspect of activity at his father's boatyard, where he worked during time away from school. From an early age, he developed a natural ability as a boat and yacht designer, absorbing correspondence courses and testing his skills from 1897 onwards, when he designed and built his first 15ft sailing dinghy, aged just 18.

He was apprenticed in boat-building to Dublin Port & Docks across the river, qualifying as a master shipwright. But his talents were such that he rose to the top in all the areas of the port which required the designing and making of specialised structures, some of them very large. So in addition to building workboats of all sizes, he played a key role in projects like the new pile lighthouse at the North Bull, for which he developed support legs threaded like giant corkscrews, and rotated into the seabed like monster coachbolts.

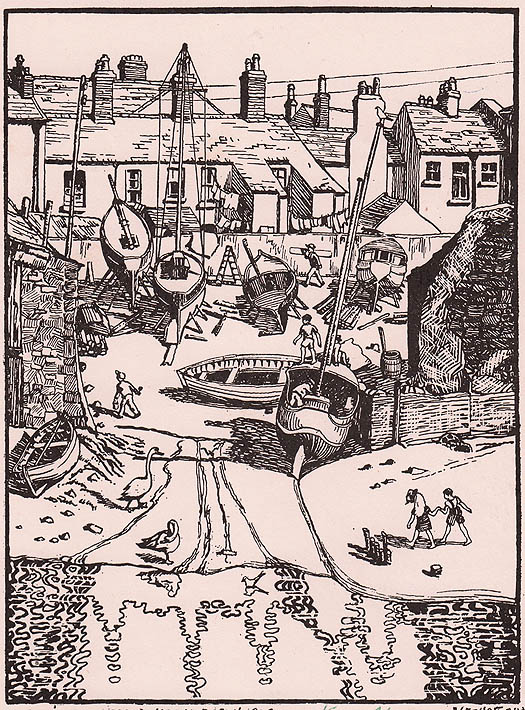

Murphy's Boatyard on the Dodder in Ringsend in the rare old times is perfectly captured in this woodcut by Harry Kernoff RHA. It was all disappeared in 1954, when the old houses of Thorncastle Street were replaced by a complex of Corporation flats of such good quality that they have recently had a major refurbishment.

He also pioneered the use of reinforced concrete for pre-fabricated harbour constructions, and when the Great War broke out in 1914, his special talents and experience were called upon to advise on quick-build ferrocement structures of all kinds. Although Ireland remained neutral as World War II broke out in 1939, the Dublin engineering firm of Smith and Pearson established a yard in Warrenpoint just across the border to build concrete barges and small ships for war work, and John Kearney was their consultant.

So far-reaching was his input into developing the infrastructure of Dublin port that when he retired in 1944, while his official title was as Superintendent of Construction Works, he was de facto the Harbour Engineer. But he couldn't be properly acknowledged as such, because he had never qualified from a third level college - it was far from universities that the Kearneys of Ringsend were reared.

However, this lack of an official title left him unfazed, for his retirement at the age of 65 meant he could concentrate full-time on his parallel career as a yacht designer, something that was so important to him that when his gravestone was erected in Glasnevin in 1967, it simply stated: John Kearney, Yacht Designer.

He had developed his skills in this area ever since his first boat in 1897. In 1901, when he was still 21, a 17ft clinker-built canoe yawl, the Satanella which Kearney designed and built for noted Dublin Bay sailor Pat Walsh, was praised in the London yachting press. Her owner camping-cruised this little boat successfully along the great rivers of Europe before World War 1, getting there simply by sailing his canoe from Dun Laoghaire into Dublin Docks, and striking a shipping deal with whichever ship's captain was heading for a port on the desired river.

Kearney had been busy for the ensuing nine years with his growing responsibilities in Dublin Port. But in 1910 he reserved a corner of Murphy's Yard, and in the next eighteen months, working in his spare time entirely by hand with the light of oil lamps, he built his first personal dreamship, the 36ft gaff yawl Ainmara, to his own design. In this his first proper yacht, he immediately achieved the Kearney hallmark of a handsome hull which looks good from any angle, a seakindly boat which was gentle with her crew yet had that priceless ability of the good cruising yacht – she could effortlessly maintain a respectable average speed over many miles while sailing the high seas in comfort.

Built in straightforward style of pitchpine planking on oak, Ainmara was highly regarded, and though the world was at war for four of the ten years John Kearney owned her, when he could sail his preferred cruising ground was Scotland. She was no slouch on the race course either. Her skipper became a member of Howth Sailing Club in 1920, and HSC's annual Lambay Race became a Kearney speciality, his first recorded overall win being in 1921 when, in a breezy race, Ainmara won the cruisers by one-and-a-half minutes.

Despite the turmoils of Ireland's War of Independence and Civil War, in the early 1920s John Kearney's position with the Port & Docks had become so secure that in 1923 he felt sufficiently confident to sell Ainmara in order to clear the way to build himself a new boat, the superb 38ft yawl Mavis, which was launched in July 1925. He was to own, cruise and race her with great success for nearly thirty years, by which time he was a pillar of the Dun Laoghaire sailing establishment – he'd a house in Monkstown, and had become Rear Commodore of the National Yacht Club, a position he held until his death in 1967.

Even with the demands of his work, and the continuing attention needed to run a yacht of the calibre of Mavis, he had found the time to design and sometimes also build other yachts of many types. What he didn't seem to have time for was simple domesticity. In later years his presence was enough to command respect, but in his vigorous younger days he could be waspish, to say the least, and a brief attempt at marriage was not a success.

Sibling relationships were also sometimes tense. Two of his brothers were boatbuilders and one of them, Jem, was almost always daggers-drawn with John. And Jem Kearney had regular battles with others, too. He was a classic Dublin character, and no stranger to salmon netting on the Liffey in circumstances of questionable legality. If one of these expeditions had been spectacularly successful, he would erupt triumphantly back into his family's little house on the East Wall Road and announce: "Pack you bags, Mrs Kearney, we're off to stay in the Gresham!" And he meant it, too. Mr & Mrs Jem Kearney of the East Wall Road became resident in the Gresham Hotel until the salmon money ran out.

So when he was building Mavis, John Kearney would only work with his brother Tom, and they were a fantastic team. But even that didn't last. One November night, working away at planking the hull, they took a break for a mug of tea at 9.30pm, and couldn't find the sugar. Each blamed the other for its absence. The row was seismic. The following night, each turned up with his own personal supply of tea, milk and sugar. And the work continued as smoothly as ever. But not one single word was exchanged between the two brothers for the remaining eight months of the project. It was years before they spoke again.

Quite what this meant when Mavis launched herself on St Stephens Day 1924 we can only guess. Like Ainmara eleven years earlier, Mavis could only be accommodated in Murphy's shed by being built in a large trench, and an exceptional Spring tide on December 26th 1924 saw her unplanned flotation. There was no damage done, but history doesn't record whether it was John and Tom who sorted the problem together despite not saying a word.

The immaculate Mavis made an immediate and successful impact, and Skipper Kearney and his beloved gaff yawl were honoured guests at regattas all along the east coast. While continuing to work full time for the Port & Docks, he kept up the spare-time yacht-building, but after the experiences with Mavis, when a regular Kearney crewmember, Billy Blood-Smyth, commissisoned a new 35ft gaff yawl from the skipper, it was client and designer who had to work together in the familiar corner of Murphy's yard to build the boat which became Sonia, launched in 1929.

Irish sailing was in a very quiet phase through the 1930s. Just about the only expanding organization was the Irish Cruising Club, and naturally John B Kearney and Mavis were on the first membership list in 1930, with Mavis a regular competitor in its offshore races, with a notable victory in the stormy 1935 race to the Isle of Man, a performance which won special praise from another participant, Humphrey Barton who was to found the Ocean Cruising Club 19 years later.

Mavis coming into port after winning the Clyde Cruising Club's annual Tobermory Race in 1938. Club rules at the time stipulated that as proper cruising yachts, the competing boats should tow their tenders throughout this race. Much effort went into designing sweet-lined dinghies.

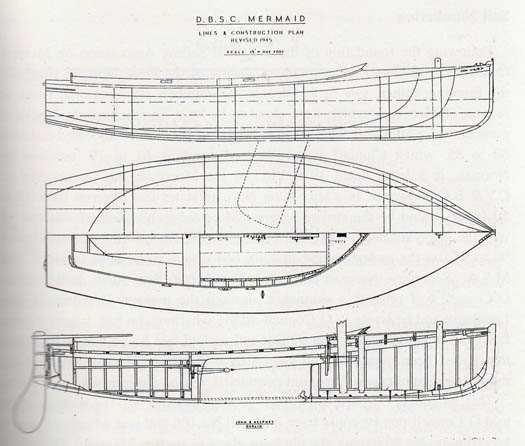

Mavis also was overall winner of the Clyde Cruising Club's Tobermory Race in 1938. But while his own sailing was going splendidly, John Kearney was concerned at the sluggish state of sailing development in Ireland. In order to give younger people an opportunity to own their own boat, in 1932 he created the design for the 17ft Mermaid, a large clinker-built sailing dinghy which was designed to be constructed for around £180 - roughly the same price as a motorbike. The Mermaid was adopted by Dublin Bay SC, but it took a long time to gain momentum, and it wasn't until the late 1940s and early 1950s that it became the most popular class in the greater Dublin area. It is still active today with nearly 200 boats built, and more than 40 took part in its 80th Anniversary championship last summer in Skerries, the winner being Jonathan O'Rourke from the National YC,while the furthest travelled was Patrick Boardman's Thumbalina from Rush, which had started from Foynes on the Shannon Estuary, home to the most distant Mermaid fleet, and had – most impressively - sailed all the way round the south coast to Skerries to mark the 80th birthday.

The Mermaid was designed in 1932 to be built at the same price as the average motor-bike

With his retirement in 1944, John Kearney's design work came centre stage, and he was busy to the end, creating more than 20 cruising yachts in all. And life in Monkstown was pleasant. Over the door of the room where he did his design work, he'd a little motto on a brass plate: "God gives us our relatives. Thank God we can choose our friends". His close friends were all from sailing, and it was a crew member who had joined Mavis in 1946, the formidable Miss Douglas, who became his friend and housekeeper and looked after him to the end of his long and remarkable life.

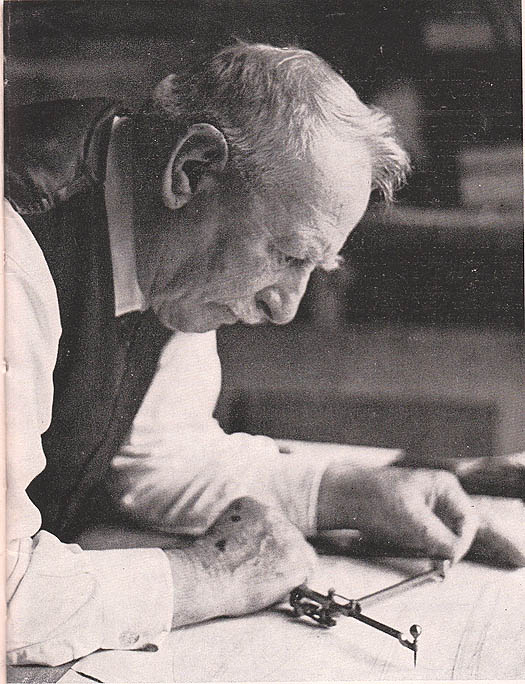

John Kearney, aged 83, working at the drawings of his last design, the 54ft yawl Helen of Howth Photo: Tom Hudson

Sonia, built 1929, cruising in British Columbia, her home waters since 1958 Photo: Jeff Graham

John Kearney's entire life is in its way a great legacy, and his fine boats are his tangible memorials. They've ventured to the far corners of the world. For instance, the 30ft Evora, a lovely Bermudan yawl which he designed for building by Skinner's of Baltimore in 1936, was last reported from Darwin in Australia. The pretty Sonia of 1929 is well at home these days in British Columbia. And as for Mavis, the crème de la crème, she is currently undergoing a painstaking restoration in Maine by shipwright Ron Hawkins, who is very encouraged by the amount of original material he is able to retain.

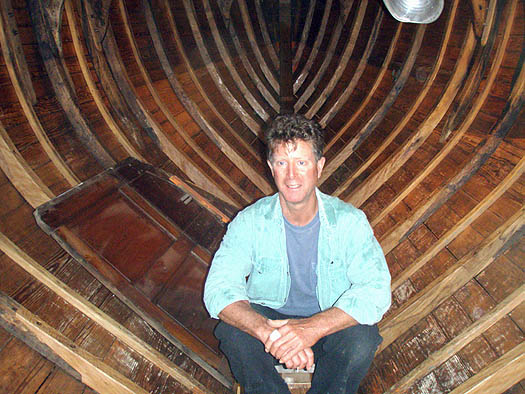

Ron Hawkins in Mavis at an early stage of his restoration project Photo: Hal Sisk

Ron Hawkins has been much encouraged by the amount of original material he has been able to retain in restoring Mavis Photo: Denise Pukas

John Kearney's first proper yacht, the 9-tonner Ainmara from 1912, has been owned for 47 years by former Round Ireland record holder Dickie Gomes of Strangford Lough. Last year, she celebrated her Centenary with a cruise to the Outer Hebrides. This year - next week in fact - she hopes to be in Dublin Bay for the Old Gaffers Association Golden Jubilee. And as it will be at Poolbeg Yacht & Boat Club, Ainmara will be back home in Ringsend for the first time in 90 years, and John Breslin Kearney will be well remembered, and celebrated too.

Still going strong. Dickie Gomes is the happy owner aboard Ainmara, which will be returning to Ringsend next week 101 years after she was built there to his own designs by John B Kearney Photo: W M Nixon

Comment on this story?

We'd like to hear from you! Leave a message in the box below or email William Nixon directly on [email protected]

WM Nixon's Saturday Sailing blog appears every Saturday on Afloat.ie

Follow us on twitter @afloatmagazine and on our Afloat facebook page