The traditional timing of the London International Boat Show as soon as possible after New Year’s Day may have been shifted about in recent years as the changing dynamics of the European marine industry and the sheer dominance through size of Dusselboot (this year’s is 21st to 29th January) have changed the map of international boat selling. Nevertheless the idea that the very beginning of the New Year is an ideal time to interest people in a new boat still holds good, as they’ll invariably be convinced they’ve thought only of gifts for others over Christmas, while their entire lives have been taken over by family festivities. So when New Year arrives, a personal treat with a change in boats is well earned. But is it necessary to get a completely new boat? W M Nixon points to a different solution.

The most significant fact to emerge from the final results of this week’s Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race is that no new boat figured in the top five places overall. All were boats of varying vintage, some quite old relatively speaking. And all had been - at the very least - tinkered around with more than somewhat, even if none had been modified so frequently and completely as the Oatley family’s hundred footer Wild Oats XI.

Admittedly Wild Oats didn’t even finish, but she was leading on the water well past the halfway stage when she had to pull out with a failed keel ram. It could well be that this was one of the few original items in the boat, for Oats has been radically changed so often - with new longer bows fitted at frequent intervals with the stern shortened still further to keep her under a hundred feet – that she now looks for all the world like a one-masted schooner.

Wild Oats XI has had so much added to her length forward and so much chopped off her stern that she now looks like a one-masted schooner

Wild Oats XI has had so much added to her length forward and so much chopped off her stern that she now looks like a one-masted schooner

Yet at no stage have any of her skillfully-executed hull mods failed. Down in Australia, and in New Zealand too, they’re past masters at doing incredible things with epoxy which, once the job has been finished, look as if they’ve been there from the start. And the fact is that when we look back on the history of sailing development, when timber construction was dominant, the more individualistic shipwrights were game to take on all sorts of challenges for they knew – or at least most of them new – just what could be done with wood while retaining the overall sea-going integrity of the much-changed vessel.

It was only when fibreglass took over as the dominant boat construction material in the 1960s that we went through a period of nervousness of configurational change, when what you got in a plastic boat stayed as what you got in that plastic boat. For a while, people were scared stiff of making any changes to what had emerged from the mould and subsequently from the finishing shop.

But if your boat happened to be of wood, or better still of aluminium or steel, you could emulate the modifiers of old and introduce changes which managed to be locally strong, and also strong within the overall structure of the boat.

Once upon a time, back in 1974, we found ourselves berthed in Crosshaven outside Eric Tabarly’s 64ft ketch Pen Duick VI after an RORC race from Cowes, which he had won both on the water and on IOR. Despite this, the great man was dissatisfied with the location of the sheet leads for the Yankee jib (he had an Illingworth-style cutter rig). So he and his lads got hold of a generator, and there before our very eyes they set up an aluminum welding workshop, cut off the eye, and re-located the sheet leads to the skipper’s satisfaction.

Only the coachroof coaming was timber - Eric Tabarly’s alloy ketch Pen Duick III was easily modified if you’d the aluminium welding kit.

Only the coachroof coaming was timber - Eric Tabarly’s alloy ketch Pen Duick III was easily modified if you’d the aluminium welding kit.

For sure there was singed paint in every direction, but the job was done, and Pen Duick won the next RORC race to somewhere in Brittany even more convincingly, while we sailed home to Howth reflecting that maybe there was more to aluminium than a rather soul-less material best used for building aircraft.

But of course we didn’t need to look very far to see boats that had been modified, sometimes beyond all recognition, in order to maintain appeal to a new generation of sailors. While the Howth 17s of 1898 may have stuck stubbornly to their original design – which they still do – the Dublin Bay 21s of 1902 had since 1963 been changed to Bermudan rig with a new coachroof.

Dublin Bay 21 in original form – they kept their crews busy, and offered scant comfort or shelter. Photo: Rex Roberts

Dublin Bay 21 in original form – they kept their crews busy, and offered scant comfort or shelter. Photo: Rex Roberts

The Dublin Bay 21s as they were from 1963 until 1986 - more easily handled, and the luxury of a doghouse,

The Dublin Bay 21s as they were from 1963 until 1986 - more easily handled, and the luxury of a doghouse,

Cork Harbour One Design with classic rig, and open cockpit. Photo: Tom Barker

Cork Harbour One Design with classic rig, and open cockpit. Photo: Tom Barker

Cork Harbour One Design in bermudan-rigged cruising mode, complete with coachroof and doghouse. Photo: W M Nixon

Cork Harbour One Design in bermudan-rigged cruising mode, complete with coachroof and doghouse. Photo: W M Nixon

And in Cork Harbour, the more senior Cork Harbour One Designs of 1896 vintage had become able little Bermudan-rigged cruisers with an extensive coachroof – complete with doghouse – which allowed them to log some very impressive cruises.

But in both cases, while the boats may have looked completely different above the deck line, their basic hull shape remained the same. Yet if you cared to look in the Coal Harbour in Dun Laoghaire, until the early years of this century a regular resident was the 32ft Bermudan sloop Bonito, which had started life as a plumb-bowed gaff cutter built in Strangford in 1884, yet by the time she reached Dun Laoghaire she was spoon-bowed and sloop rigged under the Bermudan configuration, her owner-skipper being Roy Starkey, whose regular crewmate was Bob Geldof Senr.

In fact, re-configuration seems have been a fact of life for Bonito during much of her existence, as at one stage she was yawl rigged too. But the fascination abut her lay in discerning where the constructional changes had been made to transform her appearance, and it’s a matter of regret that when her life came ignominiously to an end some time after Roy’s death, with the powers-that-be breaking up Bonito and consigning her to a landfill, it was over and done with before anyone was sufficiently aware of what was happening to ensure that her breaking-up a forensic dissection rather than a crude scrapping.

Of particular interest would have been the way in which her straight stem was lengthened into the spoon bow which became fashionable in the 1890s, and has remained fashionable with foredeck crews ever since, as it means you can work at the stemhead without being immersed in every wave, whereas straight stems – or worse still, the reverse stem as seen on CQS in the Hobart race – are a semi-permanent waterfall.

Yacht design undergoes strange mutations which can persist in exaggerated form, and one of the worst was the heavily-canted rudder which began to emerge in the 1840s when the main measurement for handicap and other purposes was along the length of the lower side of keel. The boat builder and designer Thomas Wanhill of Poole in the south of England was soon turning out boats which were significantly larger than their keel length – and hence their rating measurement – suggested, simply by increasing the angle of the rudder.

John Mulholland’s 1865-built Egeria

John Mulholland’s 1865-built Egeria

So even though the sweetly-steering schooner America with her vertical rudder came across the Atlantic in 1851 and swept all before her, in England the trend towards angled rudders persisted, and in 1865 Wanhill built his most successful schooner, “the wonderful Egeria”, a 99-footer for linen magnate John Mulholland of Belfast, and she performed like a dream despite her markedly angled rudder.

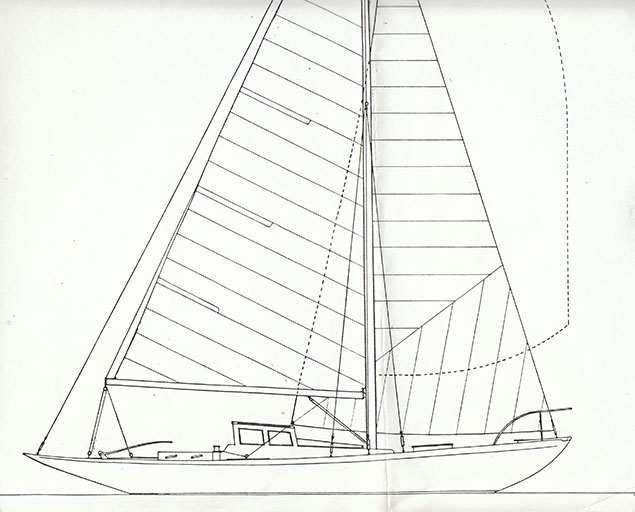

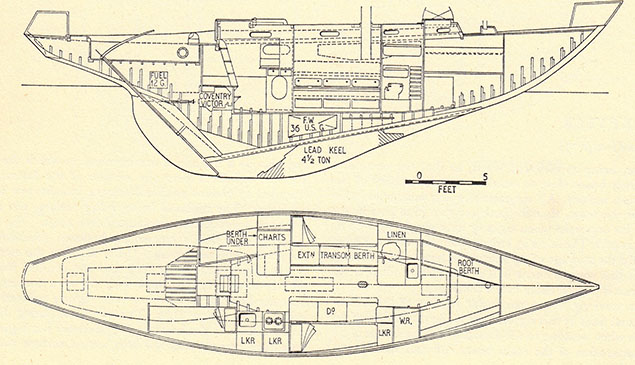

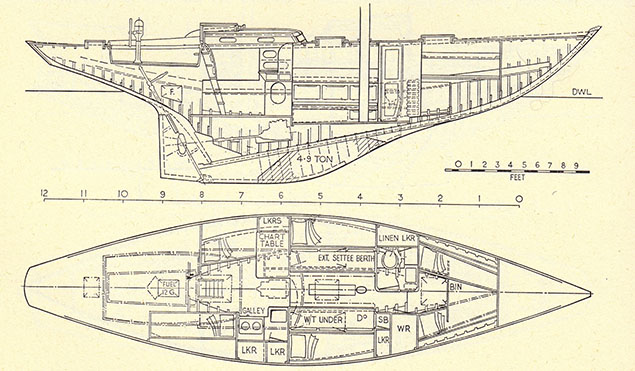

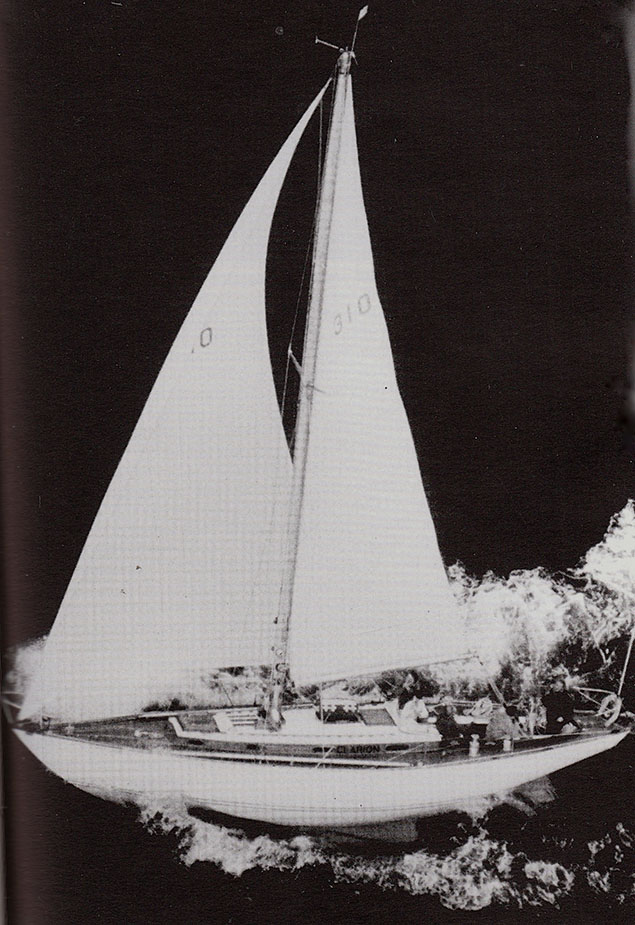

Having the angle enabled the rudder head and the tiller to be well aft to keep the deck amidships clear for crew work, but somehow the idea persisted and indeed became exaggerated until the 1960s, with the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Clarion of Wight, overall winner of the 1963 Fastnet Race, having a rudder which today looks absurd. Admittedly she was a dream to windward, but offwind and particularly with spinnaker set, she was a nightmare on the helm.

She may have won the 1963 Fastnet Race, but in her original form Clarion of Wight had carried the angled rudder to absurd levels.

She may have won the 1963 Fastnet Race, but in her original form Clarion of Wight had carried the angled rudder to absurd levels.

Clarion’s successor Firebrand in 1965 showed some modifications to the old rudder shape, but Dick Carter’s new find-and-skeg configured Rabbit won that year’s Fastnet.This particular line of development was knocked in the head when Dick Carter won the Fastnet Race overall in 1965 with his own-designed Rabbit, which was fin-and-skeg with a virtually vertical rudder, and was well-behaved on all angles of sailing. But at the time most sailors persisted in what they thought were improved versions of the old form, and in ’65 Dennis Miller, one of the part-owners of Clarion in ’63, appeared with the new similarly-sized Firebrand with a less steeply-angled rudder which had a pointed tail to give extra power at maximum depth, and that did improve things slightly. But nevertheless Firebrand continued to be the most beautiful-looking boat with the drawback of challenging helming under spinnaker, though as we’ll see, that was to be sorted in due course.

Clarion’s successor Firebrand in 1965 showed some modifications to the old rudder shape, but Dick Carter’s new find-and-skeg configured Rabbit won that year’s Fastnet.This particular line of development was knocked in the head when Dick Carter won the Fastnet Race overall in 1965 with his own-designed Rabbit, which was fin-and-skeg with a virtually vertical rudder, and was well-behaved on all angles of sailing. But at the time most sailors persisted in what they thought were improved versions of the old form, and in ’65 Dennis Miller, one of the part-owners of Clarion in ’63, appeared with the new similarly-sized Firebrand with a less steeply-angled rudder which had a pointed tail to give extra power at maximum depth, and that did improve things slightly. But nevertheless Firebrand continued to be the most beautiful-looking boat with the drawback of challenging helming under spinnaker, though as we’ll see, that was to be sorted in due course.

Meanwhile Clarion of Wight continued to be a handful, so before the 1960s were out, builder Clare Lallow of Cowes was asked to perform the then-major operation of transforming her after-body underwater to give her a fin-and-skeg configuration master-minded by Sparkman & Stephens, who were now advocating this shape with all the zeal of the convert, and in fact had used early versions of it in boats like Deb, later Dai Mouse III, now Sunstone, which had been built in 1965.

Clarion of Wight in the 1971 Fastnet Race in Rory O’Hanlon’s ownership, when she won the Philip Whitehead Cup. Her new vertical rudder arrangement is discernible.

Clarion of Wight in the 1971 Fastnet Race in Rory O’Hanlon’s ownership, when she won the Philip Whitehead Cup. Her new vertical rudder arrangement is discernible.

Thus to some extent it was the conservatism of owners which persisted in keeping the old style, and of course the vertical separate rudder had long since been advocated by designers like Ricus van de Stadt and Uffa Fox. However, getting the change to into favour with the mainstream in sailing was a different proposition altogether, and you’ll still meet those who prefer keels as long as possible with “gracefully angled” rudders, and good luck to them.

But increasingly the tendency was to the new form, and for those who cannot see any boat without wishing to modify her in some way, it was a magic time, particularly in places like Australia and New Zealand where there seems to be a skilled craftsman round every corner, and regular major boat modifications are almost a way of life.

As for the mainstream, the process was more gentle, but when the most accomplished offshore racers of their generation, the Americans Dick Nye and his son Richard, went to designer Jim McCurdy for a new race boat in 1968, the 47ft alloy-built Carina was given a conservative fin and skeg configuration complete with trim tab on the aft end of the fin keel.

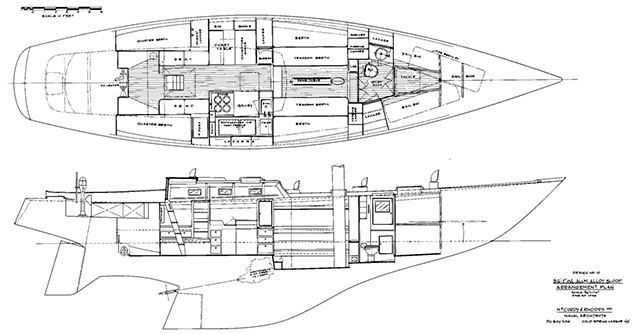

Jim McCurdy’s plans for Carina in 1968 showed a conservative interpretation of the fin-and-skeg form, and relied on a trim tab on the aft end of the fin keel to give added lift to windward.

Jim McCurdy’s plans for Carina in 1968 showed a conservative interpretation of the fin-and-skeg form, and relied on a trim tab on the aft end of the fin keel to give added lift to windward. Carina as she is today, and still winning races. She has a spade rudder and Peterson/Holland fin keel arrangement designed by Scott Kaufmann.

Carina as she is today, and still winning races. She has a spade rudder and Peterson/Holland fin keel arrangement designed by Scott Kaufmann.

But that trim tab was punished by changes to the rating rules in the early 1970s. So by 1978 they’d gone to New Zealand-born, New York-based Scott Kaufmann, and he came up with a real dream of a re-configuration with a very positive spade rudder with perfect end-plate effect on the underside of the counter, and a fin keel of the type favoured by Doug Peterson and Ron Holland.

Thanks to Carina’s alloy construction, it was a very manageable job, even if those actually doing it in Bob Derecktor’s famous boatyard found the initial aluminium grinding and cutting to be dusty hard labour. One of that work team was Rives Potts, who has now owned Carina himself for many years, and she continues to win races.

As for her seaworthiness under her new keel and rudder, that was immediately proven beyond all doubt with her successful participation in the 1979 Fastnet. But not all rudder conversions have been so successful. The lovely Firebrand ended up in America, and some owner decided she needed a fin and skeg rudder arrangement. The job was done, but then when she was sold back to Europe, the new skeg broke clean off while sailing Transatlantic. But thankfully it was an add-on rather than an insert into the basic construction, so she got across in one piece.

And then her luck turned. She was spotted by international yacht designer Ed Dubois, who fell in love with her, and decided to make Firebrand his pet boat. Her personally designed a special spade rudder which would retain the classic character of the yacht while improving the steering, and under this arrangement, between intervals of designing superyachts for other people, he had many cherished times sailing and cruising this most beautiful vanished boat before his untimely death at the age of 63 earlier this year.

It’s a great compliment to the beauty of the hull designs of Olin Stephens that a designer of Ed Dubois’s standing should not only choose one of his boats, but at the Dubois home it was a fine photo of Firebrand under sail which had pride of place above the living room fire.

So boats can go through good times as well as bad, and one much worked-on boat which is currently sitting pretty is Anthony Bell’s hundred foot Perpetual LOYAL, line honours winner in the Rolex Sydney-Hobart race, and second overall on corrected time. In that kind of company, it is an achievement comparable with Rambler 88’s performance in the Volvo Round Ireland Race back in June. Yet in all the excitement, how many now remember that back in August 2011, Perpetual LOYAL was Rambler 100, and she was very upside-down with a broken keel out at the Fastnet Rock?

Perpetual LOYAL leads the fleet out of Sydney Harbour five days ago in the Rolex Sydney Hobart Race 2016. Photo Rolex

Perpetual LOYAL leads the fleet out of Sydney Harbour five days ago in the Rolex Sydney Hobart Race 2016. Photo Rolex

Once upon a time, near the Fastnet Rock..…..Perpetual LOYAL as she was as Rambler 100 in August 2011

Once upon a time, near the Fastnet Rock..…..Perpetual LOYAL as she was as Rambler 100 in August 2011