The great solo sailing challenges of world sailing are acquiring added stature as sailing is enmeshed in ever-more-advanced technologies. With fully-crewed vessels, interest in the people involved as individuals seems to decline in an inverse ratio to the rising graph of the science in the design of boats, equipment and sails.

Yet in one area of sailing, the human interest is still paramount, even if the technology is hugely important. The solo sailors fascinate us more than ever. They are the one spark of humanity in the midst of a boat which is more like a machine than the craft we sail ourselves, and that spark of inextinguishable humanity is what we focus on. W M Nixon reports on getting together with two of Ireland’s leading soloists - Tom Dolan who is in the midst of the MiniTransat build-up circuit, and Conor Fogerty who in June had a very convincing win of the Gipsy Moth Trophy in the OSTAR – the “Original Single-handed Transatlantic Race”.

They’re a breed apart, these dedicated soloists. Get two of them together for a light lunch and a spot of shooting the breeze as happened with Tom Dolan and Conor Fogerty in Howth Yacht Club recently, and they seem just as effortlessly sociable as the next sailor.

But they have a special aura of ultimate individuality. They can live very much in the present, but you feel their longterm view is on a different horizon. People passing by who knew something of sailing wanted to shake their hands and wish them well, and made a point of doing so. It’s life-enhancing and thought-provoking, a reminder that what they do will have involved long hours, days, weeks, months, years even, of struggle just to get their boat to the starting line. And then the real challenge of racing takes over. It’s something which takes our minds off the petty problems of our own shorebound existences.

Shooting the breeze. Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon with solo sailors Tom Dolan and Conor Fogerty putting the world to rights in Howth Yacht Club. Photo: Howard McMullan

With today’s universal 24/7 communication, those ashore taking an interest in what they’re doing will feel they’re part of a team, with the lone sailor as the focus in a very sociable matrix. But the folk ashore go to their beds at night, and live normal existences during the day. The lone sailor, if he or she allow themselves to think of it, are only partially in the thoughts of those ashore. It’s a situation which if anything exacerbates the solitary nature of their position.

But that may be where the soloists are different from the rest of us. They don’t think that their’s is a long and lonely road through life at all. On the contrary, they seem to regard the desire to sail alone across vast tracts of the ocean as an utterly normal ambition, a quest whose appeal speaks for itself.

Or at least that’s the abiding impression I was left with after being with these two remarkable men. Loneliness, a fear of being completely solitary, has little or nothing to do with it. They’re so busy getting on with the task in hand, so immersed in the challenge, that the normal human reaction of seeking company doesn’t arise.

It certainly didn’t arise as a topic in the course of a wide-ranging get-together which lasted much longer than anyone had planned. The talk was of technicalities, of dealing with problems with gear and equipment, of the sheer joy when the boat is going well or when a tactic has paid off in spades. That is when these guys are most alive and carefree and fulfilled.

The good feeling when the boat is going well (and your rivals are tucked in astern). Tom Dolan heading towards an early success in IRL 910

The good feeling when the boat is going well (and your rivals are tucked in astern). Tom Dolan heading towards an early success in IRL 910

It is when they’ve come back ashore that their problems arise again. The simple pleasure of a night or two of uninterrupted sleep is savoured, and the elation of a good result can last for days. But in time, the eternal problem of finding the resources to go on with their chosen career – for that is how they regard it – will come centre stage once more, for the ultimate challenge facing a solo sailor – and particularly a solo sailor from Ireland – inevitably come down in the final analysis to funding.

In Ireland we have a small population on an island where the sea is largely regarded as the tiresome inevitability which comes with island status. That’s how most of our people look on the seas and oceans around us. Only a very few of us see those seas as a sporting playground. As for being alone afloat, it actually contravenes our seafaring regulations, but so few people wish to do it that the laws are seldom enforced.

In any case in Ireland, being conspicuously alone is something for hermits of a religious disposition. Thus the very idea of seeking to sail alone across a hostile ocean for the sheer joy and sport of it is arguably alien to the Irish way of life. Even St Brendan the Navigator had a crew. So the sailing record-keeping authorities can no longer even acknowledge the existence of a Round Ireland Solo Sailing Record. And as for any Irish sailor hoping to raise funds for a solo sailing campaign abroad in places where a certain amount of regulated solo sailing is permitted or at least tolerated, the truth is they’re ploughing a lonely furrow in every sense.

Yet when they achieve success in racing, we’re all happy to be part of it. As we’ve revealed in Afloat.ie, the way that Tom Dolan emerged from being a farm boy in Meath, through the Glenans system in its final days in Ireland until he had reached the stage that he could successfully join the mainstream of the Minitransat solo sailor setup in France, is not something of which we disapprove. On the contrary, it cheers us up no end. We joyfully saw him made an Honorary Member of the National Yacht Club, and everyone will follow his progress with avid attention towards the MiniTransat start at La Rochelle in October.

Conor Fogerty with his Sunfast 3600 Bam! back in Howth at the end of May 2016 after a Transatlantic circuit which had included winning his class in the RORC Caribbean 600 in February 2016, and making his first solo ocean crossing from the Caribbean to the Azores in April-May. Photo: W M Nixon

Conor Fogerty with his Sunfast 3600 Bam! back in Howth at the end of May 2016 after a Transatlantic circuit which had included winning his class in the RORC Caribbean 600 in February 2016, and making his first solo ocean crossing from the Caribbean to the Azores in April-May. Photo: W M Nixon

But Tom Dolan – who recently turned 30 - has succeeded in making himself part of a recognised system. The older Conor Fogerty – now definitely well into his 40s – has been a completely free spirit by comparison. He has tried a bit of this and a bit of that in seafaring. He even, for ten years, lived in the mountains of Bulgaria when he wasn’t sailing the sea. Yet somehow he has made a living of sorts as a professional sailor for 22 years.

For Dolan, sailing became the route to fresh personal discovery, and a means of escape from the humdrum prospect of life on a small farm on north Meath:

“You’ve no idea just how hard and repetitive the work of running a smaller farm can be” says he. “For me, it certainly didn’t look like the idyllic country life. When I discovered sailing – or maybe sailing discovered me - the sense of fulfillment, of rebirth almost, was total”.

He was a natural sailor, he came alive on a higher plane when sailing a boat, and while he has kept up his links from his early Glenans days in Ireland – his Glenans friend Gerry Jones who these days sails from the NYC in Dun Laoghaire is the man who beats the drum on Tom’s behalf in Ireland – he knew that he would have to base himself with the core of the MiniTransat people in Concarneau in Brittany if he was to make any progress.

Tom Dolan at a pre-race briefing during his early days in France. He has just discovered a rigging problem with his borrowed boat, and he’s still learning French

Tom Dolan at a pre-race briefing during his early days in France. He has just discovered a rigging problem with his borrowed boat, and he’s still learning French

That was more than three years ago, and the first six months were tough in the extreme until Tom acquired a fluency of sorts in French. But in time his obvious commitment to the MiniTransat ideal has seen him become part of the inner circle, while his natural talents as a sailor have taken on an added dimension, as he is a natural teacher as well.

Thus he and Francois Jambou, his co-skipper in those Mini 650 races which are sailed two-handed, have an additional useful little earner in a Sailing Academy which is attracting an international clientele. The latest country to show interest in the possibilities of Mini 650 racing is China, and they sent some wannabe sailors to take a course with Tom and Francois. The Irish sailor, with his seemingly instinctive ability to guess what a boat needs to do to go well over and above what the instruments are telling him, was intrigued to discover that while the Chinese group were totally on top of things as regards technology and getting the very best from electronics, their relationship with actual seat-of-the-pants sailing could be problematic.

This was so marked in one instance that the pupil in question was decidedly reluctant to take the tiller. That Tom has the patience and people-skills to handle and move such a problem towards a good outcome is another useful string to his bow. But for now, everything is focused on the countdown to the MiniTransat in October, and having resources in place to make the best of the events in the buildup programme.

A long way from the small damp fields of North Meath. This is what it’s all about. Tom Dolan with IRL 910, scorching away at the head of the fleet in the Biscay sun.

A long way from the small damp fields of North Meath. This is what it’s all about. Tom Dolan with IRL 910, scorching away at the head of the fleet in the Biscay sun.

The latest of these starts tomorrow, the 600-mile Transgascogne 2017 from Les Sables d’Olonne, which takes the fleet across South Biscay to Aviles in Asturias in Spain, and then returns to Les Sables.

There’ll be a fleet of sixty-plus, and while Ian Lipinsky’s extraordinary prototype Griffon.fr is expected to record her 13th successive overall win in the open division, within the 650 class Tom and his comrades in the Pogo 3s will be at it hammer and tongs. As Tom wrily remarks, having used a legacy from his late father to buy a new Pogo 3 in the most basic form available to get her ready for the 2016 season, he “made the mistake” of winning his first race with the new boat, and has been a marked man ever since.

Handsome is as handsome does…Ian Lipinsky’s one-off Proto Class Griffon.fr may be the oddest-looking Mini of all, but in tomorrow’s 600-mile Transgascogne 2017 she is on target to be line honours winner for her 13th time in 13 races. However, the real race will be in the big-fleet Mini 650s, where IRL 910 is in contention

Handsome is as handsome does…Ian Lipinsky’s one-off Proto Class Griffon.fr may be the oddest-looking Mini of all, but in tomorrow’s 600-mile Transgascogne 2017 she is on target to be line honours winner for her 13th time in 13 races. However, the real race will be in the big-fleet Mini 650s, where IRL 910 is in contention

He’ll be quite often in the lead at sea, and several times in 2017 was in a podium position at the finish. But he lies fourth overall in the season-long points series, as there has been a drought of actual first places. He’ll be aiming for one this weekend. Just before he came back for his recent visit to Ireland, he signed up in Paris with Smurfit Kappa France to confirm some much-needed sponsorship which had already been in evidence at the start of the two-handed Mini Fastnet on June 18th.

That he has found an Irish multi-national with a strong French presence fits well with his CV, but it’s only part of what is needed and his team – and Tom himself - are busy in building further funding. Right now, however, all the thought is on tomorrow’s race, and it was understandable to note at our meeting in Howth that both Tom and Conor much preferred talking about the boats and the sailing, though readily conceding that they simply had to be aware of income-generating possibilities from whatever source.

Tom Dolan’s successful progress has been made through the recognized route of the Minitransat system

Tom Dolan’s successful progress has been made through the recognized route of the Minitransat system

While Tom’s progress has been made through a recognized route. Conor Fogerty is happy enough to give the impression of making it up as he goes along. But as events of recent years have shown, and particularly the display of total rugged heroism against a brutal Atlantic in June, there’s a core of pure steel under the seemingly easy-going persona.

Conor Fogerty’s newly-acquired Sunfast 3600 Bam! coming into Dun Laoghaire at the end of an ISORA event which he’d raced two-handed. Although she may look to be the sort of boat that would need half a dozen guys on the weather-rail to get to windward, in solo ocean racing she has proven remarkably good upwind provided she isn’t allowed to heel excessively. Photo: Afloat.ie

Conor Fogerty’s newly-acquired Sunfast 3600 Bam! coming into Dun Laoghaire at the end of an ISORA event which he’d raced two-handed. Although she may look to be the sort of boat that would need half a dozen guys on the weather-rail to get to windward, in solo ocean racing she has proven remarkably good upwind provided she isn’t allowed to heel excessively. Photo: Afloat.ie

He’s from Howth, but cheerfully admits that in family terms he was the black sheep of a black sheep, and he went his own wayward way in getting into sailing. Yet by 1995 he was a regular on the crew panel of Kieran Jameson & Aidan MacManus’s much-raced Sigma 38 Changeling, building up experience to Round Ireland level and beyond as he also did his first Fastnet in 1995, and thereafter it was a giddy progression with race campaigns and delivery passages on both sides of the Atlantic as well as across it, and in the Far East too.

Around the turn of the century he met a wealthy motorboat man at a boat party. They hit it off, and motorboat man revealed his secret ambition of a round the world cruise in a nice big sailing cruiser. It must have been quite a party, but the upshot of it was that from 2001-2004, Conor and his partner were the skipper and hostess on a new Oyster 70 for a leisurely round the world voyage in which, for significant periods, they had the boat to themselves.

It was an idyllic existence while it lasted, but the fact that it was going to end at some stage suited Conor, as he wanted to get back into the racing game. This resumed almost immediately with the skippering job on Cardiff Clipper in the 2005-2006 Clipper Round the World Race. While he got into the top three on several stages, technical problems with the boat impaired a significant overall result, but after it he gradually transferred himself back into sharp end of racing while seemingly living between times in the mountains of Bulgaria.

With two solo sailors of the calibre of Tom Dolan and Conor Fogerty exchange sailing, campaign and business ideas across a table, there simply isn’t time to delve into why one of them should have made his home up high and far away in remotest Bulgaria. But it was a beneficial turn in his fortunes which enabled Conor to buy the brand new Sunfast 3600 Bam! in the 2015 season, and since then he has been able to demonstrate the true qualities of his remarkable abilities.

Bam! at the start of OSTAR on Monday May 29th 2017

Bam! at the start of OSTAR on Monday May 29th 2017

While he has returned to live in Howth and is the proud father of young Ben with Suzanne, the call of the sea is ever-present, and having gone about as far as he can go with Bam!, this morning he is in France for meetings which include getting together with the main man at the centre of organising specialist campaigns, Marcus Hutchinson, to see what might be possible.

Things may be moving quickly for Conor Fogerty, but the Bam! chapter in his remarkable sailing life has enough in it to fill a book.

Unlike Tom Dolan, he came to solo sailing at a late stage, in fact it was when he was bringing the boat back home after winning his class in the RORC Caribbean in April 2016 that he completed his first lone voyage, from the Caribbean to the Azores. This reinforced his interest in solo and two-handed events, and since then he has been building successfully on that experience such that when Bam! and her lone skipper came to the line on Monday May 29th for the OSTAR start at Plymouth, in competitive terms they were one of the most race-ready entrants.

Conor Fogerty put everything he knew into preparation for the Transatlantic race, including insisting that his sails include a Number 5 jib. The sailmakers provided it while commenting that it would probably never be used, but in one of the stormiest OSTARS ever raced, it was in use 70% of the time and played a key role in the way that Fogerty was able to open out what eventually became a 500 mile lead on any comparable boat at the finish.

Another significant win factor was to go as far north as the ice limit rules permitted . “It was a no brainer” he says. “The distance is shorter, and it gave you the best chance of being in the brief periods of favourable easterlies along the northern edge of the lows which were marching across the Atlantic.”

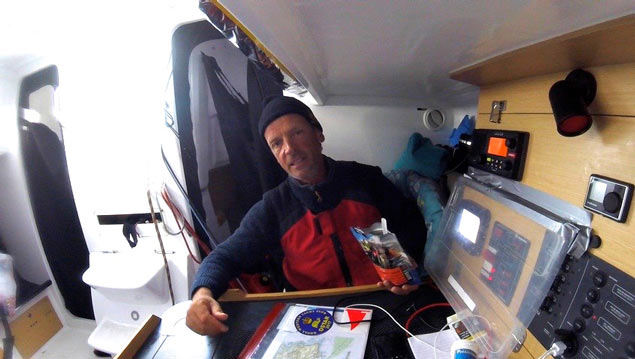

By taking a more northerly route, Conor Fogerty worked out a good lead in crossing the Atlantic, but it could be very cold and damp.

By taking a more northerly route, Conor Fogerty worked out a good lead in crossing the Atlantic, but it could be very cold and damp.

Home sweet home in mid-Atlantic. By having five complete sets of guaranteed dry clothing, Conor had the promise of some comfort.He got so far ahead that he was clear west of the uber-storm which hit the bulk of the fleet – with much serious damage for several of them – around 9th-10th June. But while they’d avoided the worst of that, Bam’s crossing was no cakewalk.

Home sweet home in mid-Atlantic. By having five complete sets of guaranteed dry clothing, Conor had the promise of some comfort.He got so far ahead that he was clear west of the uber-storm which hit the bulk of the fleet – with much serious damage for several of them – around 9th-10th June. But while they’d avoided the worst of that, Bam’s crossing was no cakewalk.

“The sea was seldom regular, let alone smooth. And the winds were mostly ahead – we could have left the spinnaker ashore. The wave patterns could be coming from every direction, and when the wind was really blowing, it exacerbated the tendency for pyramid waves to build to an ever-growing peak which would eventually collapse in unbelievable tons of crashing foam and blowing spume. God help any boat which caught got up the middle of one of those.

It happened to us several times. I remember one night I was below hoping to rest the eyeballs for a minute as the old girl was going well, and I felt her start to climb in a steepening curve which I knew would end with us rocketing out of the top of a very pointed pyramid wave. She seems to climb for ever and ever without slowing at all, and I’d time to think that a standard Jeanneau Sunfast 3600 was never built to withstand what was going to happen after the end of this ascent. She crashed out of the top into absolute black nothingness. And then she started to descend still totally airborne toward God knows what. We eventually found the sea again, with an unbelievable crash. And nothing broke. Not a thing. God bless the guys at Jeanneau.”

The going is good, but the skipper looks knackered…

The going is good, but the skipper looks knackered…

Heading into it. The sun may be shining, but what will we find in that odd-looking cloud towards the horizon?

Heading into it. The sun may be shining, but what will we find in that odd-looking cloud towards the horizon?

For power requirements, Conor used a fuel cell – he never had to run his engine to bring up the battery charge during the entire 19 days of the race, though towards the end he wasn’t getting as good a return on the cell as he’d been at the beginning.

Inevitably he was wet to a greater or lesser extent for much of the time, so his greatest luxury was in five sealed bags each with a complete change of clothes. The moment when he realised the time was right for a fresh, clean dry new suit was morale-boosting beyond belief.

While his skill in sailing Bam! so well meant he was ahead of the worst of the storm which eventually resulted in the bizarre situation where one of the fleet was rescued by the ocean liner Queen Mary 2, it has had the effect of deflecting all subsequent attention and race reports to the various rescues, and away from the fact that an Irish skipper had won the OSTAR at his first attempt.

Tired but getting there. Towards the end, increasingly flukey winds and an autohelm fault meant the lone skipper had to put in long periods of manual steering to win the Gipsy Moth Trophy.

Tired but getting there. Towards the end, increasingly flukey winds and an autohelm fault meant the lone skipper had to put in long periods of manual steering to win the Gipsy Moth Trophy.

But for those who can see past the headlines, and for those within the small high-powered circle of Irish solo sailors, Conor Fogerty’s achievement is keenly recognised, and Tom Folan proved to be completely clued in on it, while revealing that his own secret for personal comfort is a thin dry-suit within his wetsuit. Thus in yarning of this and that as our meeting drew to a close, it emerged that the two of them were aware of the up-coming signing of a contract between Nin O’Leary and Alex Thomson for co-skippering of Hugo Boss. But as both were keenly aware of any sponsor’s need to control the time of release of such news, there was no question of adding it to our agenda, and sure enough a few days later, Nin sprang it on me at a time of his and his team’s own choosing.

So now the Irish solo and short-handed sailing scene has upped its game yet further. In a week’s time, the new-look Hugo Boss show will be limbering up for the start of the Fastnet Race on Sunday August 6th. Tomorrow night, in his former skipper Aidan MacManus’s restaurant the King Sitric in Howth, Conor Fogerty will be telling his supporters of all that has happened since they last met just as he was going off to do the OSTAR, and of what he now hopes to do. And during the day tomorrow, sixty little boats will come to the line at les Sables d’Olonne to race across the Bay of Biscay to Aviles in Spain and back, and we’ll all be looking out for IRL 910, Tom Dolan, up there among the leaders where she belongs.