Displaying items by tag: Ards

Dickie Brown 1933-2014

Dickie Brown of Portaferry, builder of the Ruffian range of yachts and one of Ireland's most accomplished sailors, has died at the age of 81 after a long and well-lived life. His three abiding passions were his family, his boats and their interaction with the sea, and devoting his working career towards increasing the prosperity and quality of life in his home town of Portaferry.

Portaferry is at the far southern end of the long Ards Peninsula in County Down, set on the east side of the tide-riven Narrows which flow from the Irish Sea into Strangford Lough. The ferry service across the Narrows to Strangford village to maintain the connection with central County Down has not always been the efficient link it is today, and for much of their boyhood the three Brown brothers - Tom, Billy and Dickie – lived in an isolated town which for many was economically deprived.

However, the brothers were able to break away from the limitations of small town life. Tommy followed a career in law which resulted in his becoming Sir Thomas Brown, while Billy – after service in World War II flying from aircraft carriers with the Royal Navy - became a university lecturer in physics, electronics and engineering. But Dickie – after various youthful adventures – was determined to be Portaferry-based, and his brothers were to back him in his boat-building project with Weatherly Yachts, for which Billy was the successful designer.

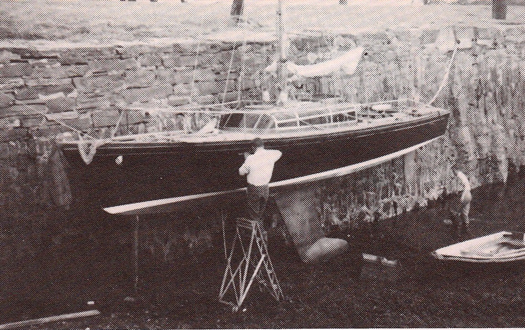

It was only after considerable experience in sailing and other areas of business that they felt sufficiently confident to set up the firm. In his younger days, Billy had become the owner of the Marie Michon, a notably hefty 28ft gaff cutter based on the Falmouth Working boat type. It was on this boat that Dickie had his first seagoing experience, so it was intriguing that when he decided to get a boat of his own inclinations in partnership with Billy in 1962, he went in completely the opposite direction, and settled on Black Soo, a 1957-built ultra-light Van de Stadt-designed 30ft offshore racing cutter of very minimal accommodation.

She was just a slip of a boat. Dickie Brown working on the topsides of Black Soo at Portaferry pier in 1964. Photo: W M Nixon

He bought the boat through her builders, Bob and Wally Clark of Cowes, thereby forming another of many lifelong friendships through which he learned much about the ways and means of running a boat-building operation and surviving in the marine industry. When Black Soo appeared for the first time in the decidedly conservative setting of Northern Ireland sailing 52 years ago, she looked sensationally different to anything else on the growing local offshore racing scene. But she successfully came through the gale-tossed first RUYC Ailsa Craig Race of 1962, and in 1963 she won it overall, going on through the mid 1960s to cut a swathe through fleets on both sides of the North Channel and in the Irish Sea, with a sensationally-fast performance in any heavy weather offwind sailing.

By 1967 Dickie had done his first Fastnet Race as a crewman, and after his second in 1969 he decided to build himself a 35-footer to his own ideas with the design created by brother Billy, who by this time had moved back to live in Portaferry and raise a family. Billy was to find that he did his best yacht design work after about three o'clock in the morning, "when the air isn't cluttered by other people thoughts".

Dickie meanwhile had married Joyce, a talented New Zealand artist, and they'd built themselves a house on the side of Bankmore Hill, right above the narrowest part of the Narrows and looking north into Strangford Lough. At the bottom of the field which now became the garden, a shed went up. It was originally planned as a pig house, as agricultural production was one of Dickie's many business interests. But soon the pigs were out, and the hull of a 35-footer started to appear instead, built upside down in three glued skins of diagonal planking and superbly constructed, for Dickie was a natural craftsman in wood.

Thus was Ruffian created, and it was a wonderful day in the early summer of 1971 when she was launched for the first time in a carnival family and community effort, the day going so smoothly, with successful afternoon sailing trials, that Joyce was moved to create a watercolour of it all, and that picture can still be seen in Portaferry today.

Ruffian made an impressive debut during 1971, but it was 1972 which saw her at her best on the offshore scene at home and abroad, winning practically everything she took part in. Yet she was already for sale, as the genesis of Weatherly Yachts was well under way, and in March 1973 the prototype of the GRP Ruffian 23, designed in Portaferry, built in Portaferry, and first sailed in Portaferry, made her successful debut.

The Ruffian 23 was the right boat at the right time. Local offshore racing was developing at many centres, and the able and attractive little performance sailer found ready buyers at home and abroad. At the height of its success, the Ruffian 23 was to be found in varying and often substantial numbers in places as widespread as Belfast Lough, Strangford Lough, Dublin Bay, the Isle of Man, Scotland, northwest England, Iceland and Hong Kong.

The prototype Ruffian 23 on her maiden sail, March 1973. Photo: W M Nixon

The right boat in the right place at the right time in 1973. The gallant little Ruffian 23 attracted adherents worldwide, and continues to race as a class in Dublin Bay and at Carrickfergus. Photo: W M Nixon

Today the class is still to be actively found in Dublin Bay and at Carrickfergus. But racing inshore and offshore wasn't the only area of success, Ruffian 23s were also cruised extensively with round Ireland ventures, and voyages to distant exposed islands such as St Kilda, satisfyingly completed. The Ruffian 23 sailors formed a maritime brotherhood (and sisterhood) which many maintain to this day, even when they have moved on to larger craft.

Weatherly Yachts also moved on to larger models, while maintaining a steady production of Ruffian 23s to provide good work in that former unemployment blackspot. New ventures included the 30ft Half Tonner Rock'n Goose (it's the local pronunciation for Rock Angus, the lighthouse-topped reef in the Narrows) which took part in the Half Ton Worlds at La Rochelle in France in 1974, and came through unscathed from a 180 degree roll in a huge Biscay storm, her survival in good order a credit to Dickie's boat-building skills. But for the next boat up in their range, Weatherly eventually settled on the 28ft Ruffian 8.5, which achieved success in a variety of ways, not least in the late Mike Balmforth's Sgeir Ban, which was fractionally-rigged to give a potent performance, and also proved herself as a very able cruiser on the Scottish and Irish coasts.

When the going was good for Weatherly Yachts of Portaferry, it was very good. But the increasing dominance of large often government-backed Continental companies in the mass-production boat-building industry meant that the longterm prospects for a small family firm in a remote location were increasingly negative. In fact, looking back, we can now realize that the Brown brothers with Weatherly Yachts hit the ground running with good ideas and a keen workforce just at the one juncture when a business with this scale and location could succeed, and they made the very best of the opportunity to provide a golden era for Portaferry.

With the firm quietly closing down after a gallant effort, Dickie was able to return to other business interests and his first love afloat – classic wooden yachts. His boat for the final long phase of his life was very different from the boisterous little plastic Ruffians, as it was the exquisite teak-built Arthur Robb-designed 42-footer Jaynor, which Dickie as a young man had watched being meticulously built by Bruce Cowley in Bangor Shipyard on the shores of Ballyholme Bay in the early 1960s.

The classic yacht for a senior sailor. Jaynor with Dickie Brown at the helm storms into the lead at a breezy Portaferry Regatta. Photo: James Nixon

Dickie Brown and his family and friends with Jaynor became a familiar sight at classic events at home and abroad, but always his first love was to be sailing from Portaferry on the waters with which he'd been engaged all his life. Eventually, ill health meant Jaynor had to be sold, but even despite his infirmities, Dickie was still able – in his 80th year – to take part and finish in the Golden Jubilee Ailsa Craig Race in 2012, one of the very few who had done the same in the first race of 1962.

The lifelong enthusiast. Dickie Brown at the helm at the finish of the Golden Jubilee RUYC Ailsa Craig Race in 2012. He regularly sailed in the race from its inception in 1962, and was overall winner with Black Soo in 1963. Photo: W M Nixon

Now into his eighties, and with grandchildren to cherish, his interest in boats and his home waters never diminished, and he had many friends to help him get afloat. My own last sight of him out in a boat was just last year. We were coming in to Strangford Narrows with the new flood, and there was a useful little fishing launch bobbing about on the bar, having come down with the last of the ebb to take advantage of any good fish coming in on the new tide.

As we shaped on our course into the Narrows, the little boat completed her brief but successful task and started to head home to Portaferry, motoring alongside us for a while to say hello. It was Dickie and some friends, in good form and out for a spot of neatly-timed fishing before Sunday lunch.

It was a moment to treasure, a good way to remember a great man of the sea and the coast, a man who enriched the lives of all who knew him. Our thoughts are with Joyce, and Richie, Fraser (a former Olympic sailor for Ireland in 2004) and Karen and the grandchildren at this sad time.

WMN

A last sight of Dickie Brown afloat on his home waters. It's August 2013, and with some friends he has come down through Strangford Narrows with the last of the ebb for some useful fishing on the bar, and is now returning to Portaferry with the new flood, nicely on time for Sunday lunch. Photo: W M Nixon