Donal O'Sullivan muses on the implications of a forgotten financial scandal at Dun Laoghaire Harbour

John Rennie, the eminent Scottish engineer who drew up the original plans for Dun Laoghaire Harbour, was destined never to see them come to fruition. He died on the 4th October 1821, many years before the harbour had begun to take its present shape.

There is not the slightest suggestion anywhere that his death was of anything but of natural causes. “The disease which killed my father was that of the liver and kidneys”, wrote his son, Sir John Rennie, FRS, in his being autobiography. (Sir John later succeeded his father in overseeing the project). There is further evidence of his illness in the minutes of the harbour Board where it was recorded, a few months before his death, that Rennie the Elder was too unwell to provide a report on the progress of the works that the harbour commissioners had been looking for.

A portrait of John Rennie (the Elder). Reproduced with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

A portrait of John Rennie (the Elder). Reproduced with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

It’s worth mentioning this all this because at one time you could meet locals who would assure you, with the utmost conviction, that “the engineer for the harbour” had put an end to his own life because, allegedly, “he put the piers in the wrong place”. That, to put it mildly, is pure folklore; suffice it to point out that that the only serious question that ever arose about John Rennie’s plans for Dun Laoghaire Harbour concerned another matter altogether - the width of the harbour mouth.

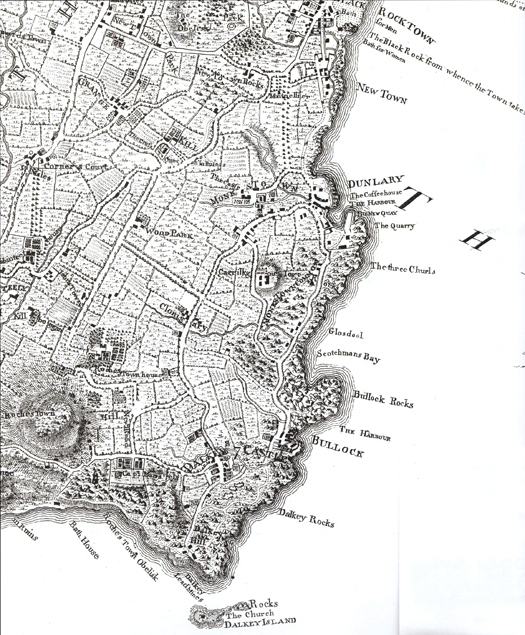

The coast at Dun Laoghaire before the harbour was built. The harbour of Old Dunleary, in the area still known as The Gut, was a shallow creek in the southwest corner of the new harbour

The coast at Dun Laoghaire before the harbour was built. The harbour of Old Dunleary, in the area still known as The Gut, was a shallow creek in the southwest corner of the new harbour

"The entrance was too narrow, they thought, for ships that would have to tack through it"

This was a contentious issue first raised by the captains of the squadron accompanying George IV during his Irish visit. It was too narrow, they thought, for ships that would have to tack through it. The contrary view, argued with much vehemence, was that a widening it would deny vessels inside the protection from easterly winds that was the primary purpose of the Harbour. The argument rumbled on for years and was finally decided when the Admiralty pressurised the Board of Works (by then in charge of the Harbour) to provide a mouth 200 feet wider than that proposed by Rennie. Perhaps the only sensible verdict on the whole matter might be the opinion in a report in 1855 of Captains Kellett and Frazer that “perfect security and facility of access are so antagonistic that one must be chosen”.

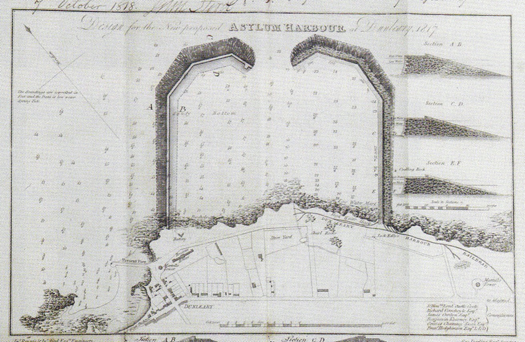

The first plan for the new harbour in 1817. The entrance was made wider in the finished version, and the West Pier was built further west to enclose the Old Dunleary harbour

The first plan for the new harbour in 1817. The entrance was made wider in the finished version, and the West Pier was built further west to enclose the Old Dunleary harbour

All that aside, while few would fault Rennie on his plans for the harbour, how some of those plans were executed is quite another matter – at least on the financial side and possibly on the technical side as well. Early in 1829, a dispute broke out between the harbour board and then - quarry contractors, Sam Smith and Bargeny McCulloch, about the use of quarry rubbish or shingle to cover the beech then existing on the shore between the piers - there were plans for a boat quay. (The original contractor was George Smith who died in September 1825 and was succeeded by his son, Sam, and son-in-law, Bargeny McCulloch).

Smith and McCulloch would have been wiser to have avoided such an argument, because it sent a financial subcommittee of the Harbour Commissioners, who were new to the job, back a to the original contract for working the quarries in Dalkey and delivering the stone to the pier heads.

What they found appalled them. Firstly there was an issue about the proportion of large blocks of stone to rubble stone - five of the former to two of the latter. The original specification on which the contract was based stipulated two to five; the proportion had been reversed by whoever drafted the contract. The large blocks were very valuable, measuring five to two cubic yards. “Many of them”, said the report, “admit of being squared or dressed so as to be used in facing or finishing the piers or quays and for which the contractors are paid 1/3d additional”. The rubble was not to be less than one and a quarter cubic foot. The stone was paid for at 3/- per cubic yard on the amounts of stone excavated “without the delivery being checked or counted in respect of the quantity or description delivered”.

But most serious of all, as they say in their report, the contract “was silent as to quarry rubbish. In fact, the use or disposal of it does not appear to have been contemplated by the contracting parties. Notwithstanding which, immense quantities were applied in the formation of both piers- but more particularly in forming the west pier—and paid for at the rate of 3/-per cubic foot “ i.e the price for the large blocks. To drive home the enormity of this, the authors of the report helpfully points out that in their letter of the 23rd of September 1829 the contractors “have offered to deliver shingle or rubbish to the beach on or between the piers at the rate of 10p per cubic yard”

Further on in the report, there is a curious observation. In criticizing the practice of “of paying the contractor by measurement without reference to the quantity or kind of material is delivered” they add the phrase ”in practice injurious to the stability of the work”.

This offhand, throwaway remark seems to have never received any attention. Understandably, perhaps, with the main focus at the time being on the financial implications which, in truth were quite serious. The report had spelt it out starkly. “Your committee apprehend that if the committee for auditing the public accounts called for the contract - they would disallow the account and report the facts to the government with their opinion thereon”. (Of the stability bit, more presently).

Nowhere in the records is there any suggestion that anyone on the harbourside had anything to gain personally from this maladministration of the contract. Neither of the two Rennies, to whom Dun Laoghaire (then Kingstown) Harbour was just one of many projects occupying their minds. Nor the Harbour Commissioners, local worthies who showed exemplary zeal in protecting the public purse. Nor John Aird, the resident engineer appointed on Rennie’s advice who certified the payments – an awkward, contrary sort of man, you might think from his letters the harbour minutes, who sometimes protected the workforce from the penny-pinching proclivities of the Commissioners. It just seems to have been one of those unfortunate things that happen in organisations when practical, busy men take their eyes of what they too often dismiss as “just paperwork”.

And yet, from the very outset, there was something odd about the Dun Laoghaire Harbour contract. Hardly had it been signed, when the Harbour Commissioners had to deal with a worrisome letter from a west of Ireland contractor called John Behan., directed to the Viceroy, Earl Whitworth He claimed that his tender was lower than that of George Smith, who had been allowed to lower his prices to bring his prices below those of Behan. He intended no disrespect to the Harbour Commissioners; he just felt that their judgement had been influenced by Rennie in favour of his fellow-countryman” (ie Smith).

Behan’s letter contained a sentence which the Commissioners must have found unsettling: Behan presumed “to think that Your Excellency may also think this matter to be of public importance, involving the integrity of public competition so eminently upheld during Your Excellency’s administration”

But Rennie deal with this smoothly enough. He, for his part, intended no disrespect to John Behan, with whom he was personally unacquainted, but he made no bones about his partiality for Smith, who had long experience in the quarrying, dressing and removing stone in the neighbourhood of Bulloch, and who had long skill in the execution of masonry of this sort. He had also a large number of workmen employed in the quarries in the neighbourhood; he, Rennie, had personal experience of the excellence of Smith’s work when he worked for him on the Howth Harbour project. There was also his fear that a higher price would have to be paid should Behan fail in the execution of his contract. Ultimately it came down to whether the commissioners had confidence in Rennie’s judgement and on that there could be no doubt or argument.

For good measure, the Harbour Commissioners added their own few tuppence. After tendering Behan, apparently, had asked that his proposals to be returned to him and then informed them that he intended increasing his prices by 12 1/2 %, which gave the Commissioners the impression that Behan did not really know what he was getting himself into.

As to the assertion that their decision “was influenced by persons in their employ in favour of their countryman Smith,” they added that they “submit that so gross and unfounded an insinuation is best repelled by the well-known honour and integrity of Mr Rennie”.

Then there was the curious matter of John Aird and Alexander Nimmo, a dispute that the Commissioners had stumbled into inadvertently. In October 1817, as the work had begun to get underway, the Commissioners appointed Nimmo, another engineer, to conduct a survey of the quarries. Aird took umbrage, claiming that the appointment undermined his own authority. He wrote a most intemperate letter to the commissioners, telling them, inter alia, how much he despised the motives that inspired the appointment.

Very much taken aback at what they had unloosed, the Commissioners asked Rennie, who had appointed Aird, what he thought. Rennie confirmed that Aird’s authority would indeed have been undermined – and indeed reflected on himself - but the letter was most unfortunate and he then diplomatically made some procedural proposals that would meet the Commissioners requirements. Nimmo soon departed, job done, supposedly, and the controversy died down. But thirteen years later, the Commissioners must have wondered whether they should have stood their ground and insisted on independent verification of what was happening at the quarries

And all this quarry shingle “immense quantities - used in the construction of both piers” which “in practice” was “injurious to the stability of the work”? The stability element, in fact, never seems to have trouble anyone overmuch, certainly not Rennie himself – Rennie fils, that is – who in a report of his site visit soon after the Commissioners’ discovery, did not mention it all.

Both the Rennies, in fact, took great pains in securing the foundations of the piers and laying down the glacis, the seaward stone slope that protects the walls of the piers. Rennie pere himself had even specified the type of mortar to be used underwater: pozzolana – a mixture of lime and volcanic ash, used in pier construction since the days of the Caesars. Not the Naples variety, he emphasises but material from another site near Rome, Cavo di San Pablo.

But now since the storm of early March 2018, that phrase “injurious to the stability of the work” has taken on a certain relevance. The West Pier took quite a battering part of the plinth of the DBSC Hut having been swept away. But at the East Pier, such was the force of the wind and wave that the sea penetrated the top of the glacis, allowing the water to gain the interior of the East Pier and the waves that penetrated the interior of the pier met no resistance - except perhaps shingle - burst open the paving at the shelter on the upper walkway. On the whole, however, the pier walls stood firm and Dun Laoghaire was spared on this occasion the type devastation experienced across the channel.

Waves lash Dun Laoghaire harbour's East Pier during Storm Emma causing substantial damage below. Photo: Michael Chester

Waves lash Dun Laoghaire harbour's East Pier during Storm Emma causing substantial damage below. Photo: Michael Chester

The broken surface at the bandstand area of the East Pier following Storm Emma in March 2018

The broken surface at the bandstand area of the East Pier following Storm Emma in March 2018

Given the current assumption that gales of this variety are likely to occur more frequently in the future, is it reasonable to accept that Dun Laoghaire Harbour will continue to be able to withstand the extremes of weather that are supposed to come our way? Knowing what’s inside some parts of the piers, you might wonder.

Repair work shows the extent of storm damage to the East Pier Photo: Afloat

Repair work shows the extent of storm damage to the East Pier Photo: Afloat

Coming back to the matter of the Smith contract – the firm had become Smith and McCulloch since the founder George Smith had done in September 1825 - things could not continue as before. There was a legal problem, however in cancelling the contract and the Solicitor-General was not optimistic that the jury would find in the Board’s favour in relation to some aspects of the dispute. In fact, everyone involved was tainted to some extent, including the Commissioners had acquiesced in paying the account and their resident engineer who had signed it. There was also the matter of the thirteen years during which the irregularities had gone unchallenged.

However, he recommended an expedient: oblige the contractors to adhere to the strict letter of the contract and deliver large block stone and rubble at the proportion of five of the large stone to two of rubble. This was clearly impossible and the Smith and McCulloch, recognising that the game was up, withdrew from the contract on the 25th January 1830. A new quarrying contract was later signed with another firm, Henry Mullin and McMahon.

A view from the south looking over Dun Laoghaire Harbour Photo: Peter Barrow

A view from the south looking over Dun Laoghaire Harbour Photo: Peter Barrow

The Board of Works took over Dun Laoghaire harbour on the 31st July 1832 and in the name of efficiency immediately made a clean sweep of the entire harbour establishment. (You might wonder if they knew what had been going on in the quarries) Aird’s salary was reduced from £500 to £300; they were not reducing Mr Aird’s salary as such, they told him –they were just announcing their intention to employ an engineer at £300 a year. Aird was possibly under some stress at the time. He had a stroke some months later- on the 26th November and died on the 8th October the following year.

"His request of a loan of a cart to bring his belongings to Dublin was turned down"

George Darling, the very able secretary and accountant to the outgoing board, was dismissed, there be no longer any need for his services. He went blind at this time and was being assisted by his son, Charles. His request of a loan of a cart to bring his belongings to Dublin was turned down.

The Board of Works testimonial read: “ He has performed his duties in a most efficient and praiseworthy manner”, adding the ungracious qualification “as far as their limited knowledge of the affairs of the harbour will admit them to form a judgement”. Darling must have got some satisfaction a year or two later when they had to send him quite a polite letter asking for his help with a legal issue.

And the Smiths? They went into house building and some of their houses are still standing today. Not unexpectedly, their building methods could be open to scrutiny. One house owner, failing to drive in a nail into a wall to hang a picture, found behind the plaster a block of granite. From Dalkey quarry no doubt. A few feet away, no problem at all – just shingle mixed with horsehair.

Much of the above first appeared in a book on the history Dun Laoghaire written in Irish by the former Hon. Secretary – O Kingstown go Dun Laoghaire. It was published in 1976 by Foilseachain Naisiunta Teoranta

The sources are chiefly the minute books of the proceedings of the Commissioners of Kingstown Harbour, Board of Works, National Archives: OPW Piers & Harbours. Part 1. 1/8/6/1-5 and 1/8/7/1.