Displaying items by tag: Baily

Who Runs Dublin Bay, The Capital's Waterborne Playground?

#dublinbay – Who runs Dubli Bay? Dublin is gradually getting to grips with the sea. Ireland's relentlessly growing and developing capital city is learning that interactive living with the sea and the city's River Liffey, for trade and recreation alike, should be a natural priority for a major coastal conurbation of this status and potential. Thus, formerly derelict industrial waterfront and dockland sites are being re-configured for recreational and hospitality use. And Dublin's ancient maritime communities are learning more of their maritime heritage, and how it can be better understood, both to make these areas more attractive to live in, and to attract visitors. W M Nixon highlights some recent events which show the way forward, but begins by wondering just who's in charge?

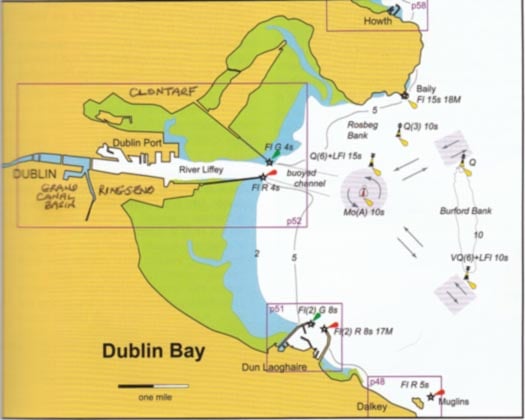

It's a good question. For starters, what is Dublin Bay? To keep things as simple as possible, let's agree that Dublin Bay is the area westward of a line between The Baily headland to the north and the Muglins to the south, enclosed then by a dogleg south of Dalkey Island across to the mainland's Sorrento Point at the lower end of Dalkey Sound.

As to how far westward you can reasonably include waterways in the navigable bay area, for simplicity we'll discount the two canals – the Royal and the Grand – radiating from the docks, except for their dockland basins. And as for the River Liffey itself, at high water it may be navigable as far as the weir at Islandbridge, but for most craft, height restriction means that you can go no further than the Matt Talbot Bridge, and even then you're relying on the opening of the Eastlink and Sam Beckett bridges.

So in all we're looking at an area about six nautical miles north to south at the most, and seven miles east to west. But as the east-west dimension is only three miles of open water at low tide, we're looking at a very busy little bit of sea, where multiple uses can often result in potentially conflicting interests trying to share space with each other, while demands on the relatively small sections of accessible waterfront can become acute.

Time was when there was a clear pecking order among the port and bay users, based on commercial demands and the social status of the different activities. Within Dublin port, the Port & Docks Board was effectively its own empire. It had to function effectively, wash its face in financial terms, and get on with the job - and that was it.

While some individual members of the Board may have been concerned with its public image, as perhaps were some of the employees, for the most part it was in the business of making money out of handling ships and their cargoes, and the bigger the better, and that was it – they definitely weren't into public entertainment or the accommodation of the needs of smaller craft. Thus in Dublin as at other ports throughout much of the world, small boat ventures and fishing in particular got little attention – fishing boats and their crews had to make do as best they could with often woefully inadequate facilities.

But as recreational boating developed, new factors came into play. Money talked, and it could be the case that the new breed of recreational sailors were themselves board members or senior professional employees of the Docks Board. And as the new asylum harbour at Dun Laoghaire had developed from 1817 onwards, recreational sailors had the social and economic clout to secure themselves key sites for their private club facilities at this attractive new location.

But that was then. Nowadays, the old system of each interest looking only to its own concerns, and everyone minding their own business if at all possible, just doesn't work any more. The city is bursting at the seams with a new vitality seeking fresh recreational expression, and access to Dublin's maritime heritage. Public and semi-state bodies such as Dublin Port are expected to be much more aware of their image, not only for the general good, but because it has been shown that people much prefer to be working for an organization which is well thought of in the larger community. This means that even the most commercially-minded members of the Port board accept that in the long run it makes economic sense to hold open days, Riverfests, "fun for all the family" happenings, and so forth.

But as this outgoing approach develops, somebody has to be running the show. So who's in charge of the greater bay area? At national governmental level, at the very least the requirements of the Marine Section of the Department of Agriculture and whatever are relevant. So are those of the Departments of Transport, Tourism, and the Environment.

Then there's Local Government. The north side of the bay comes under the Independent Republic of Fingal, which also touches the western navigation limits of the Liffey, as Fingal somehow incorporates the Phoenix Park. Then Dublin City takes over in the inner bay, but South Dublin may think it has some sort of say-so on the innermost bits of the Liffey to the southwest. Southeast of Dublin port, and you're very quickly on the Golden Road to Samarkand, in other words you're into Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown.

A busy little bit of water. Everyone wants a piece of the action on Dublin Bay. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

You'd think that's all enough to be going along with, but bear with me. As far as administration of the built waterfront environment administration is concerned, we're only starting. King of the scene has to be Dublin Port, which really is the big beast in the administration arena. But snapping around its heels on both sides of the Liffey is Waterways Ireland, which has its canals north and south of the River. While WI may have allowed a reduction of the Spencer Dock going into the Royal Canal, across the river the sea-lock-accessed Grand Canal Basin on the south side has the potential to be the jewel in the Waterways Ireland crown, as it has a location to die for and the kind of industries which local authorities dream of – if California has its Silicon Valley, Grand Canal basin is Dublin's Silicon Harbour.

Despite the all-Ireland spread of its remit, Waterways Ireland is a smaller creature than Dublin Port, but you get an increasing sense of boundaries being claimed and defined as this once forgotten area of Dublin docklands comes rapidly alive. And of course another player in our list of statutory authorities which are very interested in the administration of the Dublin Bay area is the Docklands Development Authority, or whatever it's called now in the hope that we'll forget the debacle over the Irish Glass Bottle site.

So our chums in NAMA also have a decision-making role. And then, back in the water, the fact that the Liffey is a living river means that Inland Fisheries is another body than can be rightfully involved, as can organisations concerned with the well-being of those two important tributary rivers, the Dodder to the south and the Tolka to the north.

Sometimes it can seem too crowded for comfort. Ships and smaller craft share a narrow bit of water at Poolbeg. Photo: W M Nixon

All this complexity of administration in the Dublin Bay waterfront may seem convoluted enough already, but we haven't even got to Dun Laoghaire yet. There, the local council have put up the gross new library building as though to offend the other buildings on the established waterfront just as much as possible, while the Harbour Company is actively seeking ways of increasing its income – largely through accommodating cruise liners – as Dublin Port has been hoovering up the cross-channel car, passenger and ro-ro traffic through economies of scale.

Doubtless there are other statutory bodies which may be able to declare a legitimate interest in the running of Dublin Bay, but that's enough for now, so let's look instead at the consumer organisations. At a rough count, I can come up with twelve yacht, boat and sailing clubs, eight of which have premises. There are also at least six coastal rowing clubs, and five sea angling clubs. And there are several national boating bodies, all of which inevitably see a numbers concentration of their membership in the Dublin area, even if they conscientiously ensure that their administration reflects their nationwide nature.

If we really wanted to spread the net, we could come up with significant organization numbers for kite-surfers, windsurfers, canoeists and kayaks too. Plus there are two excellent links golf courses with their clubhouses right in the bay, on Bull Island. And finally, let's not forget Dublin Bay's own very special landmarks, the unused Smokestacks of Poolbeg. Boat users definitely want to keep them – at the very least, they tell us where we are. So we now have the ESB – or is it Electric Ireland these days? – central to a decision which is of great interest to Dublin Bay users.

By all means, let us know at Afloat.ie if you think there's a real need for some overall authority for the bay which can maintain the balance between sea and land, and between work, trade and recreation. It might seem like a good idea. But do we really need yet another level of bureaucracy? Yet another group of Jacks-in-Office who may even have staff with peaked caps and regulatory authorities which enable them to interfere with our natural freedoms?

It's a moot point, but I'll conclude with some experiences of how Dublin Bay is coming along as a genuine amenity for all, and look at some areas of developing interest. Of course, not everything in the garden is lovely. A public event which may have been a good idea on its first staging can become a bit jaded in its second year round, and this seemed to be the case with Dublin Port's Liffey Riverfest.

Last year, it had the attraction of novelty, and it included some Tall Ships, and also the major visit of the Old Gaffers Association international fleet in their Golden Jubilee Year. There was a busy shoreside carnival and many waterborne events including the Ballet of the Tugs and a race series for the historic Howth Seventeens. The restaurant Ship, the MV Cill Airne, provided an excellent administrative and hospitality centre, while downriver Poolbeg Yacht Boat Club's marina provided a very effective main base. It was all great fun.

The "Restaurant Boat" MV Cill Airne has proven very popular with visiting sailors in Dublin Port, but they'd like it even more if they could berth right at the ship. Photo: W M Nixon

So this year they extended the Riverfest to maybe five days in all, and for many who had been there in 2013, it seemed a bit jaded. They'd stepped up the shoreside entertainments, and noisy "fun for all the family" meant less fun for those afloat. The Howth 17s had dutifully turned up to put on a demonstration race or two, but this time round it seemed to be seen as no more than handy background moving maritime wallpaper. And as for the waterborne Ballet of the Tugs (now a daily occurrence throughout the Riverfest), those of our crew who had been there in 2013 said it wasn't nearly as good as last year, but one who hadn't been there in 2013 couldn't believe this - he thought it was absolutely marvelous seeing it for the first time.

The Waterborne Ballet of the Dublin tugs Shackleton and Beaufort impresses those who haven't seen it before, but old Riverfest hands are always looking for something new. Photo: W M Nixon

The Howth Seventeens do their duty with racing in the Liffey in the Riverfest, but for a fickle crowd on the quays always seeking fresh entertainment, the classic old boats are really just a form of moving wallpaper. Photo: W M Nixon

The Seventeens doing what they do best – getting in a bit of real racing. This is the leading group headed for the Clontarf At Home in July, and then on to Ringsend for Echo's Centenary Party at her birthplace. Although Echo (number 8) was the birthday girl, Deilginis (No 11) won the race to Clontarf.

Nevertheless, the old Howth Seventeens had done their duty by the Riverfest at the beginning of June knowing that later in the season, they'd have a weekend completely tailored to their own needs. The Lynch family's Howth Seventeen Echo was built in Ringsend in 1914, the only boat of the class to be built in that ancient maritime community of boatbuilders and sailmakers. So in July the class had their traditional race round the Baily to the Clontarf Yacht Boat Club At Home - an event which is totally tide dependent – then as the tide started to recede, the Seventeens got themselves round to hospitable Poolbeg.

There they were given a snug berth within the marina (most welcome as a giant cruise liner came up the river), then after a Centenary Party in PY & BC which is as near as boats can now get to Echo's birthplace in Ringsend, the party went up the quays to the Cill Airne for a dinner hosted by the Lynches, then after over-nighting at Poolbeg, on the Sunday they sailed home – mostly crewed by families – with a fair wind for Howth to round out a perfect couple of days.

The Howth Seventeens were very glad they'd been put in an inside berth at Poolbeg Marina in July after coming round from Clontarf, as the 113,000 ton cruise liner Ruby Princess was next up the river. Photo: Cillian Macken

The Ruby Princess goes astern into her berth in Alexandra Basin with her bow only yards from boats in Poolbeg Marina. Photo: Cillian Macken

In other words, it was exactly the kind of weekend that most classic local one designs will enjoy hugely, but as entertainment for non-participants and spectators, it wouldn't have registered at all. This is the quandary which harbour authorities have to cope with in trying to give themselves a human face. You're either into boats and other waterborne vehicles, in which case almost anything to do with them is wonderfully entertaining. Or else you're not, in which case total incomprehension, and the ready seeking of almost any other kind of entertainment – and the noisier the better - is almost inevitable when you try to get general public interest and involvement.

Obviously the visit of a significant Tall Ships fleet is something whereby a port authority can combine both genuine maritime interest and public entertainment, but securing one is a major challenge. However, in Dublin port the new user-friendly attitudes have seen the extension of the pontoon beside the Point Depot just above the Eastlink Bridge, and while the rally of the Cruising Association of Ireland was a matter of the crews of around forty boats getting together and enjoying themselves rather than some high profile public entertainment happening, it certainly provided a useful insight into what boat visitors expect in a port.

The Cruising Association of Ireland fleet was a fine sight at the new pontoon.......Photo: W M Nixon

....but because of the need to keep the fairway through the Eastlink Bridge clear, they could only raft three deep. The blue boat in the foreground is Wally McGuirk's own-built 40ft steel Swallow, the last design by O'Brien Kennedy. Photo: W M Nixon

So I might as well start with the bad news. A forthright opinion came from the most experienced cruising man present. In a notably experienced group which included Wally McGuirk's very special own-built steel 40-footer, Swallow, the last boat to be designed by O'Brien Kennedy, being the most experienced is quite something. But whatever it means, it doesn't necessarily include diplomacy. When I asked this most experienced of all the cruising folk present what he thought of the new pontoons, he briskly replied: "They've put them in a stupid place. They should be up beside the Cill Airne, which is where everyone wants to be, and not down here beside the Eastlink Bridge with the likelihood of noisy crowds coming out of the Point Depot at a late hour, and the traffic on the bridge, which also means that we can only raft three deep in order to keep the channel under the bridge clear".

In fact, the CAI's end-of-season rally had a problem of success. Forty boats turned up to provide an impressive fleet but the most they could have at the pontoon, even with rafting, was thirty, so ten had to return through the bridge to Poolbeg where they'd been hospitably received the night before.

Once again, choosing the Cill Airne as the venue for the night's entertainment and meal proved a success, so ideally what's needed is berthing pontoons surrounding the ship herself. It would be mighty convenient, and also solve the inevitable security problems inherent in berthing in a city. But quite what shore-based hospitality establishments in the area would make of a ship in the river receiving such preferential treatment in the guiding of everyone's potential customers is another matter.

While the sea lock into the Grand Canal Basinon the south side of the Liffey went unoccupied the CAI fleet milled about to find berths on the North Quays. Photo: W M Nixon

However, across the river through a sea lock into the Grand Canal Basin, and you're into a snug and secure place that is surely a popular cruising destination that's just waiting to happen. Admittedly in Ireland people seem to have an aversion against having to transit a lock to enter port, but as they'll already have had to come through the Eastlink, having the lock ready can be part of the package. Within, you're totally secure, safe from big ships in the river and within easy reach of many facilities, including even the Daniel Liebeskind-designed Grand Canal Theatre.

The total shelter of the Grand Canal Basin beside the Liebeskind-designed theatre. Photo: W M Nixon

Even with other users such as trainee windsurfers and the Viking Splash ambhibian using the rad Canal Basin, there is still plenty of room for visitors. Photo: W M Nixon

Now that it has been sold to people of taste and discrimination, presumably we can hope that its clumsy current name of the Bord Gais Energy Theatre can be changed pronto. Admittedly there used to be a beloved little venue in Dun Laoghaire in the 1950s and '60s which was the Gas Company Theatre, and many a sailing person enjoyed an entertaining night of drama there. But times have moved on, and even public utilities have to be given more interesting and original names. Certainly when you have a situation where people unfamiliar with the First Official Language think that Ireland's newest and most glamorous place is known as the Bored Gosh! Energy Theatre, then something drastic yet creative has to be done.

Being in and around the Grand Canal Basin – which dates back to 1796 – really does give a sense of the past, even if many of the buildings are very new. But just across the River Dodder is Ringsend, and that is a place which is re-discovering its history as one of Ireland's most interesting maritime communities.

The view northward down the River Dodder from Ringsend Bridge towards the Point Depot on the other side of the Liffey. The entire riverbank on the right used to be a mix of boatyards and other marine businesses, but all that was swept away when the Thorncastle Street Dublin Corporation flats were built in 1954. Photo: W M Nixon

A packed house in Poolbeg Y & BC on Thursday night heard Cormac Lowth talk on the distinctive Ringsend sailing trawlers, and how they traced their development directly back to the arrival of Brixham trawlers from Devon, which were able to begin fishing the Irish Sea in 1818 a couple of years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Brixham was a hive of fishing development and expansion at the time, and their fleets ranged the seas between Dublin Bay to the northwest and Ramsgate in Kent to the east. They originally were enticed to the facilities at the little Pigeon House harbour down along the South Wall, but soon crews were settling, such that nowadays in Ringsend there are still several prominent surnames which can be traced directly back to Devon.

With the Irish community established, there was much intermarriage, and the locals soon acquired the imported skills. Ringsend in those days was almost an island, and with its characterful fishing community, it attracted artists such as Matthew Kendrick and Alexander Wiliams, both of whom lived in Thorncastle Street, the main thoroughfare where the houses backed onto the River Dodder, along whose banks marine industries prospered.

Ship-building flourished, and one of the most talented families in this craft was the Murphy clan, who built on the banks of the Dodder (and then themselves fished) one of the mightiest cutters of them all, the 70ft St Patrick. But the demands of sailing such a boat with the standard crew of just three men and a boy were such that subsequent boats of both Brixham and Ringsend were ketch-rigged, and it's the ketch-rigged 70-footers such as Provident which we know as the classic Brixham trawler today.

Provident, built in 1924, was one of the last and one of the best of the famous Brixham sailing trawlers.

The 28ft Dolphin, built in 1924 in Ringsend, was a final acknowledgement of the hundred year old link to Brixham. She is seen here on Strangford Lough in the 1960s in Davy Steadman's ownership. Photo: Ann Clementston

Provident was built in Devon in 1924, by which time steam was already displacing sail as the preferred power system for trawlers. The effects of World War I from 1914-18 and the War of Independence in 1921 had further reduced the already much-weakened direct links between Brixham and Ringsend, but in 1924 the young designer-boatbuilder John B Kearney built Dolphin, a 28ft clinker-built gaff ketch, in Ringsend. Her design was a final salute to the Brixham connection, for in shape she was completely different from all Kearney's other yacht designs.

Dolphin has sailed through these columns before, but she deserves to be remembered again. And Cormac Lowth's wonderful lecture – it was utterly brilliant - brought the thought of her back to mind, for she's still around. So if anyone wants to make a small fortune, they first should first make a very large, indeed an enormous fortune, and then undertake the challenge of restoring Dolphin. She lies in a very sorry but still just about restorable state in a boatyard on Cork Harbour. Put her right with your large fortune, and you can be reasonably sure of having a small fortune at the end of it, but thre'll be a job which was well worth doing properly completed.

A very sad sight – Dolphin as she was in July 2014, at a boatyard on the shores of Cork Harbour. Photo: W M Nixon

#dublinbay – A lighthouse perched on the Howth peninsula on the north shore of Dublin bay and one of the most well known lights for mariners entering the capital's waters has been captured by youtuber Sky Pixels Ireland. The three minute video captures beautiful sunny aerial scenes flying around the Baily Lighthouse, Howth, Co. Dublin, on the east coast of Ireland.

Queen Elizabeth Arrives on Dublin Bay

Impressive Views from Dublin and Cork Waterfront Properties

This semi detached holiday home is situated on an elevated site with uninterrupted harbour views just a five minute scenic walk to the village.

Baltimore is a renowned sailing centre with its three sailing schools and two diving centres. Regular ferry trips will take you to the nearby islands of Cape Clear and Sherkin with its lovely sandy beaches.

Vaulted ceilings to dining area, Oak timber beams, open fireplace, teak stairs, paved patio areas are some of the attractive features of this property.

The asking price is €465,000. All the details plus lovely photos here.

The second property to catch our eye while wandering round Howth head in the past fortnight is a detached dormer bungalow, with spectacular uninterrupted sea-views over Dublin Bay. The property is tucked away in a secluded and very private location beside Howth Summit for €650,000. Great views here.

Moth Dinghy Debuts on Dublin Bay

Since our report on Ireland's debut at the Moth worlds in January it was inevitable that one of these high speed sailing dinghies would appear on Irish waters soon enough. Yesterday, John Chambers took his first tack of 2011 on Dublin Bay in a Moth he bought in France. Clearly the high speed foiling craft did not go unnoticed. It got an immediate thumbs up from the nearby DMYC frostbite fleet sailing their penultimate race.

The Bladerider Moth came blasting back from the Baily lighthouse, according to eyewitness accounts. It has hydrofoils on the dagger board and rudder which lift the boat out of the water when sufficient speed is achieved.

It is Chamber's intention to sail the innovative dinghy in this Summer's Dublin Bay Sailing Club (DBSC) summer season.

Video of the Dublin Bay sail plus a photo from Bob Hobby is below:

Moth sailing on Dublin bay. Photo: Bob Hobby

Moth sailing in Ireland on facebook HERE