Your mainsail vang (or kicker) is the sail control all of us know. For those of us who grew up sailing from a young age, we’ve had it from Optimists to Lasers, to keelboats and beyond. But do you know when to use it, and as importantly, when not to? In this article, Graham Curran of UK Sailmakers Ireland takes us through some of the do’s and don’ts of mainsail vang trim.

What is the Vang for?

Your mainsail vang is used to control the vertical movement of your boom. When your mainsail is hoisted and filling it will naturally try to lift your boom – the vang holds the boom down. As a result your vang directly limits the amount of twist in your mainsail.

As we transition from upwind, to reaching, to downwind, in various wind conditions – the vang’s role changes and becomes more, or less, important depending on the situation.

For the purposes of this article, we will assume we are sailing a keelboat with a traveller car and mainsheet setup.

Pre-start and Mark Roundings

During pre-start and at the weather mark you should have a set vang tension to apply. In 10-12 knots of wind sail upwind. Have your mainsail tell tail breaking 50% of the time. At this point, pull the slack out of the vang and apply a coloured tape mark to your vang piston where the purchase block lies. Use this as your ‘mid vang’ setting for pre-start and mark roundings to ensure your boom does not rise unintentionally – check this for the conditions you are sailing in and adjust accordingly.

Upwind

Never, never, never have your vang on while sailing upwind. A crucial component of efficient upwind sail trim is twist. Different amounts of twist are needed depending on the prevailing wind conditions.

When sailing upwind twist should be controlled using mainsheet tension, and correct twist determined using the mainsail tell tails. If your vang pulled on hard you will not be able to add twist by easing the mainsheet.

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard – “take the slack out of the vang” – while sailing upwind. Doing so instantly limits the amount of twist in the sail to whatever is there at that precise moment.

When the boat falls into a lull and the mainsail begins to stall more twist is needed – the main sheet is eased, but nothing happens, so the mainsheet is eased more and more until the tell tail eventually flies – but now the entire mainsail has been left to leeward, the slot has shut, and the boat feels lifeless. If the vang was left slack the boom would be able to rise and the mainsail would twist at the top – bringing the tell tail to life – without losing power from the lower sections of the mainsail, and without dropping the boom to leeward and closing the slot.

When the boat is hit by a gust the mainsheet is eased to depower the sail and unload the helm but, as above, the vang holds the boom down, not allowing the sail to twist, so more mainsheet is eased and the mainsail begins to backwind due to closing the slot. With a slack vang, the boom is allowed to rise when the mainsheet is eased. The top section of the mainsail twist open and reduce the power of the sail where it has the most effect due to the law of the lever. The slot remains open and free as the boom rises rather than being left to leeward, and the helm unloads allowing the boat to accelerate.

When sailing upwind ignore the floppy rope at the mast and resist the urge to pull it tight. Never pull your vang on upwind.

When to pull your vang on upwind

I know, I said never pull your vang on upwind. But in some circumstances it can help, two specifically:

1. In light wind and choppy conditions, it can help to have the vang on hand tight to stop the boom from bouncing erratically. Constantly check that your twist is correct using your tell tales, adjust your vang tension to a good ‘middle ground’ setting until some breeze fills and the sail becomes more stable.

2. In very heavy airs where your traveller is completely to leeward and you are still easing mainsheet to keep the boat upright. In this situation, the mainsail will begin to completely flap and flog when the mainsheet is eased. As we all know – “a flappy sail is not a happy sail” – it will provide no power and cause a lot of drag. It is more efficient in the scenario to pull your vang on to tighten the mainsail leech, to stop it from flapping, and ease the mainsheet to ‘bubble’ the luff of the sail while keeping power in the leech. You are in effect driving off the leech of the mainsail. When in this situation ensure your outhaul and Cunningham are pulled on hard, and your backstay is at maximum tensions to flatten the mainsail as much as possible without inverting it.

Reaching

When reaching the vang main is the only control which effects mainsail twist. As your boom is eased beyond the quarter of the boat the mainsheet is no longer effective at holding the boom down, so the vang takes over.

A good indicator of good vang tension is if the top batten as close to parallel with the boom as possible, usually ending up at 25° off parallel.

We are all familiar with the panicked “BLOW THE VANG!” call, often it comes far too late. When tight reaching in windy conditions it is important to be proactive rather than reactive with the vang, especially with a spinnaker up. Don’t wait for the call, have the vang in hand and feel the boat. If the angle of heel begins to increase rapidly in a puff then ease the vang until the heel angle stops increasing. Let the puff roll through. When the boat begins to flatten after the puff pull the vang back on slowly, continuously feeling how the boat is reacting.

Running

As with reaching the boom is eased further outboard when on a run. The mainsheet is now completely ineffective at controlling mainsail twist. Pull your vang on to keep your top batten parallel to the boom. This keeps the mainsail fully projected to the wind and causes the most drag which, contrary to other points of sail, is exactly what we are looking for when sailing downwind in displacement mode.

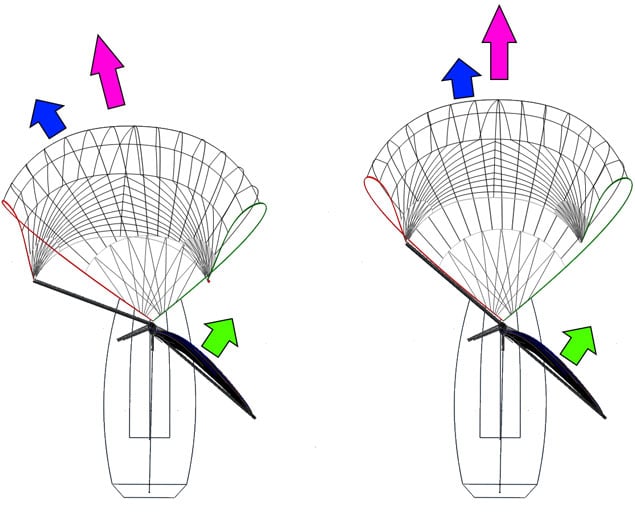

A common and fatal mistake when running downwind in heavy airs is blowing the vang when the boat begins to roll downwind.

This roll is caused by the spinnaker and the mainsail becoming unbalanced. Instead of the resulting forces pushing the boat forward, it drags the boat to windward, initiating the roll sequence.

If left uncontrolled this roll eventually leads to an unintentional jibe and broach (see photo below).

The solution to this problem is to equalize the forces of the spinnaker and mainsail. This is done by both easing the pole forward and sheeting on the spinnaker, or by powering up the mainsail by ensuring the vang is at the correct tension and pumping the mainsail into the centre.

Sometimes a death roll can occur suddenly and cause panic. In this panic someone blows the vang, thinking it will prevent a broach, as it does on a reach. The opposite happens, the mainsail depowers completely, the little green arrow disappears, and the spinnaker happily drags the boat to windward, jibes the boat and someone, usually the bowman, ends up with wet feet.

Set your vang tension using the top batten angle to the boom as a guide, and do not blow the vang to solve a death roll downwind.

Conclusion

This is certainly not an exhaustive breakdown of how to use the vang. More so some guiding principles to start with. Every boat is different, what works on some does not work on others. Some boats such as SB20s and other sports boats rely heavily on the vang for mast bend. In order to find the best solution for your boat you need to start from a baseline – I hope this is what we have provided in this article.

The vang is one of those underappreciated sail controls which is often not given much thought. Ultimately it can have a major effect on the performance of your boat. Next time you are out sailing give the vang some extra thought and see how it is used on your boat currently – experiment, assess, and learn.