Displaying items by tag: Dublin Bay 21

Dublin Bay 21 Revival & Ilen Restoration Get On-Site Consultation With Classics Designer Paul Spooner

The restoration of classic yachts and traditional craft to the recognised international standard is still relatively new in Ireland writes W M Nixon. In fact, it could be argued that the major project in Dunmore East, completed in 2005 on the 1894 G L Watson-designed 37ft cutter Peggy Bawn, is still the only example we have in Ireland of the painstaking and meticulous research and work of the highest quality that is required on a vessel of this size for total authenticity.

The Peggy Bawn project was for maritime historian Hal Sisk, and while Michael Kennedy was the lead shipwright, many specialist talents were involved in creating a widely-admired masterpiece.

Hal Sisk aboard the restored 1894 Peggy Bawn in Dublin Bay in 2005. In the background is the Jeanie Johnston – in those days, she still sailed. Photo: W M Nixon

Hal Sisk aboard the restored 1894 Peggy Bawn in Dublin Bay in 2005. In the background is the Jeanie Johnston – in those days, she still sailed. Photo: W M Nixon

Now Hal Sisk is working on a completely different idea, a revival of the legendary Dublin Bay 21 class, the famous Mylne design of 1902-03. But in this case, far from bringing the original and almost-mythical gaff cutter rig with jackyard topsail back to life above a traditionally-constructed hull, he is content to have an attractive gunter-rigged sloop – “American gaff” some would call it – above a new laminated cold-moulded hull which is being built inverted but will, when finished and upright, be fitted on the original ballast keels, thereby maintaining the boat’s continuity of existence, the presence of the true spirit of the ship..

It’s a fascinating and complex project to which we’ll be returning in future postings on Afloat.ie. For now, the first DB 21 to get this treatment is Naneen, originally built in 1905 by Clancy of Dun Laoghaire for T. Cosby Burrowes, a serial boat owner from Cavan who had formerly owned Nance, the 1899 Dublin Bay 25 which was the only DB25 to be built by designer William Fife’s own yard in Fairlie – she still sails in the Mediterranean, now under the name of Iona.

As for Naneen, she was soon under new ownership as Burrowes interests turned elsewhere. She raced with the class in Dublin Bay under the original gaff rig until 1964, and then under the masthead Bermudan sloop rig, which kept these attractive boats going as an active racing class until August 1986.

In that fateful year, the after-effects of Hurricane Charlie in Dun Laoghaire Harbour resulted in their damaged hulls of the Dublin Bay 21s being retrieved and stored in a Wicklow farmyard while everyone worked out various schemes to make good use of this historic flotilla of seven very significant and attractive boats.

Hal Sisk and DB21 “Guardian” Fionan de Barra, after much research, have now developed this moulded hull/simpler rig philosophy which revives the class while retaining its character. And in Steve Morris at Kilrush in County Clare, they have a skilled boat-builder who has already shown with the Shannon cutter Sally O’Keeffe and other projects that he brings very special talents that work well in a wide variety of boat-building challenges.

The proposed rig for the new-style Dublin Bay 21s will be a variation on this rig which Alfred Mylne designed for the DB21 sistership Zanetta, which was built in Scotland for a Clyde owner in 1918, but was used as a cruiser and never joined her sister-ships in Dublin Bay

The proposed rig for the new-style Dublin Bay 21s will be a variation on this rig which Alfred Mylne designed for the DB21 sistership Zanetta, which was built in Scotland for a Clyde owner in 1918, but was used as a cruiser and never joined her sister-ships in Dublin Bay

However, in order to maintain the integrity of the project, the actual design of the Dublin Bay 21 hull had to be agreed to very close limits, far removed from the free-and-easy approach of boat-builders in the early 1900s. For this, they have been able to draw on the highly-trained skills of designer and classics consultant Paul Spooner, who worked with Duncan Walker’s famous Fairlie Restorations company for twenty years, and has seen through some extremely demanding projects thanks to his fully-qualified status as a naval architect and engineer.

Using Paul Spooner’s drawings, the work in Kilrush has been proceeding steadily since late summer, and in recent days a stage had been reached where Paul Spooner’s presence was required on-site in order to finalise some key decisions. But he’s a very busy man, so to optimize his presence here, Hal Sisk linked-up with Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Project of Limerick and Baltimore, as the riggers developing the restored sail-plan of the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen had also been seeking Paul’s expert advice on their work.

While logistically challenging, it was all just possible in three recent days, and despite freezing damp weather in the west, Paul Spooner put in useful time in Kilrush where Steve Morris’s work is a joy to behold, and then he was transferred to the care of the Ilen team and whisked from Limerick to Baltimore.

Paul Spooner (top right) with some of the Ilen team aboard the ship in Baltimore with the restored wheel steering system. With him are (top left) Jim McInerney and James Madigan (wooden boat builder), on wheel is Tony Daly (Shannon fisherman & wooden boatbuilder), while right foreground is Matt Dirr (“Builder of Curved Structures”). Photo: Gary MacMahon

Paul Spooner (top right) with some of the Ilen team aboard the ship in Baltimore with the restored wheel steering system. With him are (top left) Jim McInerney and James Madigan (wooden boat builder), on wheel is Tony Daly (Shannon fisherman & wooden boatbuilder), while right foreground is Matt Dirr (“Builder of Curved Structures”). Photo: Gary MacMahon

There, in The Old Corn Store in Oldcourt Boatyard where Ilen has been re-born, many assembled parts that we’ve seen recently on Afloat.ie being built in the Ilen Boat-Building School in Limerick has now been fitted in the ship, and here too the Paul Spooner presence brought reassurance that they were working in the right direction.

As for which direction Paul Spooner himself was going, it would have been overly-demanding for any lesser man. But having given advice of gold dust quality to two major restoration projects in Ireland, he then hopped on a plane in Dublin Airport and went to Japan, where he is being consulted on the restoration of a large 1927-vintage Camper & Nicholson ketch. That’s how it is at the leading edge of classic restoration projects.

Dream on…..Ilen School’s Matt Dirr in thoughtful mood aboard Ilen after the new Limerick-built footwell has been installed on board in Baltimore. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dream on…..Ilen School’s Matt Dirr in thoughtful mood aboard Ilen after the new Limerick-built footwell has been installed on board in Baltimore. Photo: Gary MacMahon

What's The Way For Dublin Bay's Classic Boat Sailors?

Last week's Sailing on Saturday blog about the fate of classic yachts was a revelation about our readership. Although three significant historic vessels in three different and distant locations were involved, it was the news about the re-build of the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle which drew nearly all the attention. Cork Harbour may indeed be the true capital of Irish sailing, but the sheer size and wealth of the South Dublin population accessing the sea through Dun Laoghaire gives it special power and interest. As someone whose home port is outside Dublin Bay, W M Nixon happily returns to the fray.

It's little wonder that Ireland has won more than her fair share of Nobel Prizes for Literature, yet frequently has to look abroad when boats need to be built. We're great at working words into packages of merchandisable literature or high-flown arguments, but we're maybe not so good at building boats, or even looking after them.

But then, Albert Einstein was a keen sailing man, yet despite his intellectual genius, his boat was always a bit of a mess. So maybe it's all of a piece, that last weekend's story about – among other things – the re-build in France of a classic Dublin Bay 24 of 1948 vintage, has in the space of a few days evoked thousands of beautifully-crafted words in the comment section with enough heat generated to warm a small town. (to read comments scroll to the end of last Saturday's blog here – Ed)

Some of the big beasts of Dun Laoghaire's sailing jungle have enthusiastically thrown their hats into the ring, and already we can imagine some shrewd producer of Cable TV docu-dramas setting out a potential cast list for the likes of Roger Bannon and Hal Sisk, while the mysterious Michael Joseph will be played by The Man In The Iron Mask.

The irony of it all is that all these commentators aspire to the same thing – increased vitality and enthusiasm in Dun Laoghaire sailing. And sometimes, if they would take more time to read each other's detailed comments, they'll find they broadly are advocating the same methods of providing boats which will set the local sailing imagination alight, rather than being just another set of plastic fantastics.

But because of the Irish habit of "wanting nothing to do with that other crowd," a lot of creative diplomacy is needed to harness all this energy. Maybe an intense level of debate is unavoidable. For as we've said of another venerable Irish classic boat class which manages to survive and prosper, it does so by inverting the laws of physics, and relying on friction to create energy.

Let's begin with the most straightforward query – Michael Joseph's first question, posted on Wednesday 15th October, as to why do we think that the setup in Dun Laoghaire is not conducive to the preservation and continuing vitality of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, in other words the Dublin Bay 24s?

Well, basically it's because Dun Laoghaire has great difficulty in getting some of its acts together. It's physically a very fragmented sort of place. The relationship of the town with the harbour has always been problematical, and it's difficult to generate a general sense of maritime community which might be conducive to encouraging classic yachts which need to be well loved.

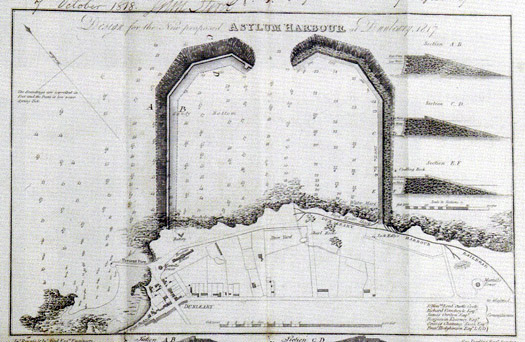

When the plans for the new "Asylum Harbour" were drawn up in 1817, it was seen purely as a shelter facility for shipping caught out in in adverse weather in the Dublin Bay. Although there was a tiny quay at Old Dunleary (the area is still known as The Gut), in the initial plan it was actually shown as being outside the new harbour. The thought that the crews of ships anchored in this new port of refuge might wish to have direct contact with the nearest bit of shore seems if anything to have been actively discouraged.

The proposed pans for an Asylum Harbour in 1817 did not include any suggestions as to possible in-harbour locations for jetties and quaysides, let alone waterfront development, and it actually excluded the small quay at Old Dunleary to the west, though in the final form the West Pier was moved further west to enclose the Old Dunleary pier.

This meant that when the inevitable shoreside facilities began to develop rapidly, it was all on a piecemeal basis. Ideally, when the plan for the harbour was finally agreed, a parcel of property of the same area as the harbour itself should have been secured on the waterfront for the planned development of a complete harbour town. But instead, you got opportunist growth - not really development at all. An unattributed quotation about 19th Century Kingstown, as it had now become, in David Dickson's recently published mighty tome Dublin (Profile Books) tells us much about the official view of the way things had got out of hand in the new seaside town, with speculative developers such as Mr Gresham from the Gresham Hotel putting up terraces of houses every which way:

".....no system whatever has been observed in laying out the town so that it has an irregular, republican air of dirt and independence, no man heeding his neighbour's pleasure, and uncouth structures in absurd situations offending the eye at every turn."

Ouch. For a growing conurbation which prided itself on being called Kingstown, that "republican air of dirt and independence" was a low blow. But as the new railway in 1834 had cut most of the new town off from the sea, an effect which was to become further emphasized by roads running parallel with it, the opportunities for dynamic interaction between town and harbour were restricted. Thus any waterfront space became too valuable to house the workshops of master craftsmen, boatbuilders and shipwrights who might be expected to be readily available to build and maintain local classes of wooden yachts of any significant boat size.

Modern Dun Laoghaire looking northwards, though it should be noted that this photo was taken before the contentious new library was forced into the waterfront between the Royal Marine Hotel and the National Yacht Club. With the water edge's almost exactly marked by the railway and the roads parallel to it, this clearcut division means that, far from the waterfront being part of a shared urban-harbour complex, the complete lack of planning in the early stages has resulted in very little comfortable inter-action between harbour and land, and there is precious little space available for locating specialist small boatyards and marine workshops which would facilitate the continuing good health of substantial wooden classic yachts.

So nowadays, the reality is that basing a cabin sailing yacht of any reasonable size in Dun Laoghaire on a year round basis is too expensive already without the added cost of her being a high-maintenance classic. The best value for money in Dun Laoghaire at the moment is probably provided by a Sigma 33 or a First 31.7 raced as a One Design. Yet in both cases, the necessary membership of one of the waterfront yacht clubs and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, added to the expense of a marina berth and the most basic running costs, means an owner-skipper is shelling out around €10,000 per annum before anything much has been done with the boat.

So although Dublin Bay Sailing Cub works wonders in co-ordinating the racing of hundreds of boats, the survival or otherwise of a class is dictated not by policy decisions on promoting new classes by DBSC, but rather by ruthless market forces, with the sheer expense of sailing from Dun Laoghaire dictating which classes can hang on when times are bad.

The result is that over the years, the surviving classics have become steadily reduced in class numbers, and only the smallest boats survive. With the loss this year of the 17ft Mermaids as an officially recognized Dublin Bay class, as they could no longer guarantee the minimum fleet of five boats, only the 25ft Glens survive from the former serried ranks of several wooden keelboats, and only the 14ft Water Wags survive of the once numerous wooden dinghies.

Yet the growing health of the Water Wags – which can trace their history back to 1887 as the world's first One Design Class - suggests that even in the cut-throat accountancy-led world of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, people still have a natural fondness for classic wooden boats. The current fleet of robust Water Wag dinghies are to a design adopted in 1904, and it adds to their attraction that although they were supposedly designed by local boatbuilder James Doyle, it's generally agreed that the real designer was his talented daughter Maimie.

Mind the gap........ Some of the fleet of a dozen and more classic Waterwags which departed their home waters of Dublin Bay last weekend to race in County Roscommon on the North Shannon's Lough Boderg. Photo: Guy Kilroy

The class have an instinctive sense of their own community, with mutual assistance in maintenance and honing sailing skills a natural part of the healthy mix. One of the factors which has increased their viability is the huge improvement in boat road trailers, for although they remain firmly based in Dun Laoghaire, from time to time you find they've upped and left and gone off for a weekend's racing at some strange and distant location, which might well be described by the management wonks as a bonding exercise

Last weekend, they were having their annual North Shannon Regatta. One of the keenest owners, Guy Kilroy, has a farm in Roscommon on the west shore of Lough Boderg, and the Water Wags descended on him in force. Despite the presence of the great Jimmy Furey building his classic sailing dinghies at Leecarrow on the west shores of Lough Ree, you'd never have thought of Roscommon as a sailing county, but there you go. However, while the coastal Autumn leagues at Crosshaven and Howth saw the seasonal mists soon dispersed, on Boderg in the middle of Ireland it took a long time for the fog to lift. But when it did, the sailing was sublime, and they got in two good races, with four boats level on points, but Ian and Judith Malcolm in the 99-year-old Barbara won on the countback.

Wags-in-a-mist. While the seasonal mists soon cleared at the Autumn Leagues on the coast at Crosshaven and Howth, in the heart of Ireland on Lough Boderg the fog lingered. Photo: Judith Malcolm

Lots of TLC. They may be in the reeds, but the maintenance mustn't be done in a rush.....The high standard of TLC on the Water Wags – the oldest chime in at 110 years – is a wonder to behold. Photo: Ian Malcolm

When all the loving care becomes worthwhile – perfect racing on Lough Boderg last weekend for David McFarland's Moosmie (15) and Vincent Delany's Pansy (3), with Killian Skay's Maureen (29) and Scallywag (44, David Williams and Dan O'Connor) in gentle pursuit. Photo: Guy Kilroy

Maintaining a Water Wag is a very manageable business, but inevitably as the recession recedes, there'll be noises about reviving larger wooden classics, and there's a feeling that the Mermaids aren't completely finished in Dun Laoghaire harbour just yet. There was an interesting twist to this in 2014's Mermaid racing, as the National Championship at Rush was won by Jonathan O'Rourke of Dun Laoghaire's National YC.

Despite being up in Fingal's Rogerstown heartlands where in recent years they've built some supposedly hyper-competitive Mermaids with the clever use of epoxy, Skipper O'Rourke's boat is the 1960 Grieves Brothers built Tiller Girl, which is surely a hopeful sign for the class's future.

The age-defying champion. Mermaid Champion 2014 Jonathan O'Rourke (National YC) with his 1960-built Grieves Brothers boat Tiller Girl. Despite there currently being no racing for Mermaids in Dun Laoghaire, Tiller Girl won the Nationals at Rush even though she was in the area where new supposedly lighter Mermaids, using the exoxy wood system, have recently been built. Photo: W M Nixon

Well, hello Dolly! Named after the world's first cloned sheep, the cloned GRP Mermaid Dolly (white hull) was built in the hope of revitalizing the class, particularly in Dun Laoghaire. But even though she only had a fiberglass hull shell with the rest of her – including the mast – in wood, the new concept was rejected by the class. So Dolly is now based at Sag Harbor in the Hamptons on Long Island in America, where she is much admired, while three of her sisters have proven very to be very durable and effective training boats at a sailing school in West Cork.

Nevertheless, it's at this time of the year that the hassle of maintaining a clinker built wooden boat comes centre stage yet again, and I have to confess that when Roger Bannon produced the fibreglass-hulled Mermaid Dolly, I thought she was a super boat and still do, but the class elders decided otherwise.

Moving on up the size scale, we return to the battleground of the Dublin Bay 21s, still mouldering in a Wicklow farmyard. I only once sailed on one of them under their classic gaff rig complete with jackyard topsail, and despite the enormous spread of cloth, was very impressed by how light and responsive they were on the tiller, but then we were racing in a gentle breeze.

The Dublin Bay 21s await their fate in a Wicklow farmyard

However, this constant refrain about them acquiring dangerous lee helm in strong winds seems to me to be a result of the primitive mainsail arrangement, with the tail of the mainsheet led directly from the counter to cleats on the cockpit coaming. This gave very poor levels of sail control in squalls, and often when the helmsman requested that the mainsheet be quickly but carefully eased to give him better control and keep the boat more upright, it would instead be let go with a run, the mainsail would then be flogging out of control, the close-sheeted headsails would force the bow off, the end of the long mainboom would then hit the water causing the sail to fill with the boat now on a reach, and over and under she'd go.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

So it could well be that if a re-built class of Dublin Bay 21s ever emerges, that then they might be given an added safety factor by having the mainsheet led forward, guided close along the underside of the mainboom, and then come down the aft side of the mast to be controlled by a winch on top of the coachroof.

As to whether or not we'll ever see the 21s race again, the odd thing is I think this week's intense exchange here on Afloat.ie may have brought it all a bit nearer. Because if you plough on through the icy politeness of the initial exchanges between Hal Sisk and Roger Bannon, I think you'll discern that they both reckon a cold moulded multi-skin timber hull construction to be a very viable option.

Roger Bannon points out that building a completely new hull on the ballast keel of the original boat is recognized under maritime law as being the continued existence of the same boat, which somehow is an oddly heartening bit of information when you look at the utter dereliction of the DB 21 hulls today.

Could this be the future for the Dublin Bay 21s? Beautiful multi-skin construction under way on Steve Morris's 32ft Harrison Butler designed classic at Moyasta near Kilrush. If it's adopted for the revival of the Dublin Bay 21s, as several of the boats would be buit in one batch construction could be facilitated by the inverted hulls being built on a male mould, thereby making the work easier for newcomer to boatbuilding working on a community basis.

Photo: W M Nixon

And as for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra, they've been considering seriously the work being done by Steve Morris near Kilrush in building a cold-moulded classic cutter to Harrison Butler's Khamseen design. Steve was the lead builder in constructing the superb gaff cutter Sally O'Keeffe down in West Clare. So when you see his work on his new boat, all things seem possible, particularly if it's agreed that the new Dublin Bay 21s should be cold-moulded in multi-skin timber on inverted hulls in a maritime community project in Dun Laoghaire, as the basic work would be relatively unskilled, and everyone could have a go at it.

For, as the success of the wonderful CityOne dinghy project in Limerick has shown, in sailing the building of the boat can be as much part of the experience as the subsequent time afloat. But if we ever do see the Dublin Bay 21s sailing again, let it please be with the proper rig. Everyone seems to be pussy-footing around the idea of a more easily handled semi-gunter configuration, maybe with just one jib. What's the point of all that? This isn't meant to be Easy Street. Let's have the full jackyard tops'l and cutter rig and all the bells and whistles, or let's not bother at all.

Should the Dublin Bay 21s be re-built, it has been suggested that for ease of handling and project management they might in future use this simpler "American gaff" rig, as seen here on Zanetta which was built on the Clyde in 1918 to the Dublin Bay 21 design.............

,,,,,but here at Afloat.ie, we reckon that would be the wrong approach. If you're going to have a new Dublin Bay 21, then she should have all the classic bells and whistles and more sail than is good for her, just as we see here with the Ringsend-built Innisfallen having a bit of sport with her spinnaker in the 1950s.

The Boat from Buttevant Brings Home the Bacon

#sailing – With all the high-profile Irish entries in the RORC Caribbean 600 race falling by the wayside in this year's breezy staging of the sunshine classic, it has been left to two hard-working charter boats to do the business for Ireland, and they've done us proud.

Appropriately, both boats are owned by people who are involved with the wind energy business. The bigger of the two, the Farr-designed 100ft Cape Arrow which has placed 13th overall, is owned and managed by Tuskar Shipping, which is in turn owned by Fastnet Shipping, a Waterford company which is run by Sinead and Trevor O'Hanlon and specialises in servicing the offshore wind industry.

Cape Arrow is professionally skippered by Andrea Balzarini. But the other Irish front runner, the 76ft Lilla which has won Class 1 and placed 8th overall, has owner Simon de Pietro of Kinsale YC very much hands-on as skipper, while his wife Nancy is the navigator. They demonstrated their joint skills last year by winning overall in the cruiser division in the biennial Newport-Bermuda Race, but this time round they'd their boat going so well they had the class win in the open division.

Both of them maintain close ties with Ireland. Her people are from Sligo, while his mother lives near Buttevant in County Cork and is co-director of the Buttevant-based family firm, DP Energy. The company is in the forefront of wind harnessing technology, and is also at the heart of the major project to install a huge tidal farm with multiple turbines in the ferocious streams which run off Islay in the southwest Scottish Hebrides, with the turbines being serviced from Northern Ireland.

That particular challenge would be enough for most people, but as well they manage Lilla as an active charter boat, fitting their occasional races around an active working programme when the boat is skippered in choice cruising locations by Ian Martin. It's a busy life, and there's extra interest in that Lilla is now something of a classic – she was built in Bordeaux in 1993 in aluminium to a Philipppe Briand design. Thus the win in Class 1 in the Caribbean 600 made for a nice 20th birthday present for a boat which is still as good as new, and very elegant with it.

The annual sprint around the islands with the Caribbean 600 provides an opportunity for some of the biggest sailing charter boats to show how they can go like the clappers if given the chance, and it provided some intriguing results even if the prime positions were largely as predicted. Thus the line honours winner as expected was Mike Slade's 100ft Leopard, though she was five hours outside the record time set by George David's Rambler 100 in 2011, which was a decidedly mixed year for that big boat, as by mid-August she was upside down off Barley Cove with her keel gone AWOL in the Fastnet Race.

On corrected time, again as expected it was a battle between Hap Fauth's Judel Vrolik 72 Bella Mente and Ron O'Hanley's Cookson 50 Privateer, with the latter having a well-deserved win by 22 minutes. So that's all right, then. But maybe the real story is when we delve into the other boat times, and note that the schooner Adela placed third overall on IRC, and finished just half an hour after the out-and-out racing machine Privateer.

Adela is a massively big - as in enormous - 180ft steel-built schooner, designed by Djikstra and built by Pendennis in Falmouth in 1995. To blast round the course in a machine like this in a way which enables her to sail up to her rating with such impressive style is just a fantastic achievement by skipper Greg Perkins.

Admittedly when you see Adela out of the water, it's to realize she's not so much a wolf in sheep's clothing as a cheetah in haute couture. Above the waterline, she's all sweeping counter and elegant clipper bow, but below it she's a workmanlike fin and skeg profile which really does give her performance a lot of oomph.

Even so, the loads which a boat this size imposes on her sails, rig and equipment is something which can only be partially measured electronically. There's a huge element of experienced judgment in driving her to the limit without seriously breaking something, and to do it round a course like this which involves frequent directional changes shows skill of a very high order. So let's hear it for the big steel lady.

And spare a thought for those who dropped out. The 100ft Liara skippered by Peter Metcalf from Northern Ireland hadn't got very far from the breezy start when her mast came down, while damage to both the 78ft Whisper (Mark Dicker) and the First 40 Lancelot II (Michael Boyd, Niall Dowling and John Cunningham) likewise saw them under the DNF category. As for the storm-battered Irish-owned Swan 48 Wolfhound which was registered DNS, she may still be out there somewhere around 70 miles north of Bermuda. Her crew were taken off in a severe storm by a ship which heard their EPIRB, but when last seen in atrocious sea conditions, Wolfhound was still afloat.

BERMUDA RIG IS FOR WIMPS

Those crusty old Dublin Bay salts who have been dumping big time on this blog for our enthusiasm for the Dublin Bay 21s in their original gaff-rigged form, bashing us with their negative memories of near-sinkings and actual sinkings and hellships that generated lee helm when the mainsheet was let fly in strong winds, they may well think we've retired hurt from the fray. Not a bit of it. We've only been re-arming. Now we'll let them have it with both barrels.

What on earth do they think the original owners had in mind when they ordered the boats in the first place? Were they looking for comfortable little cruisers to doddle around the bay? Not a bit of it. They were looking for boats suitable for wild sportsmen, not for boats approved of by conservative seaman.

Of course the Dublin Bay 21s were demanding and difficult and sometimes dangerous to sail. That was what it was all about. There's no sport in safety. And of course they were hard work, and an ergonomic disaster area in terms of ease of handling. That's the way life was in 1902, and the ways of the sea were supposed to be harder than the cosseted life ashore. So let's take a look at another photo of a Dublin Bay 21 under her original gaff rig with jackyard tops'l, and see why they represented such an awful but irresistible challenge.

In steady conditions, the Dublin Bay 21 under full sail was manageable, but she provided a real challenge when sailed hard in a blow.

The photo must have been taken in the late 50s, with the boat setting what was to become her last suit of gaff sails. Though they're bearing up reasonably well, a certain bagginess would exacerbate any helming faults. The tiller is well across, suggesting marked weather helm, but don't forget the rudder was well raked, which exaggerated the appearance of the amount of helm necessary, and as the boats aged there was increasing flexibility – to put it mildly - in the connection between rudderhead and tiller.

Thus basically the boat is quite reasonably well balanced. But imagine what happens if a sudden squall strikes. As our old salts have pointed out, the narrow side deck means that the Dublin Bay 21s start to fill with Dublin Bay through the non-self-draining cockpit quite quickly. The mainsheet must be eased as quickly as possible. The ergonomics are terrible, with the mainsheet controlled from cleats outside the cockpit coaming, so a lot of the time in a sudden wind increase the mainsheet – with its tails in a jumble below – is simply let fly, thereby immediately and completely altering the balance of the boat. It would defy all the laws of centre of effort and centre of lateral resistance if she didn't suddenly develop marked lee helm.

So the skill lay in controlling the easing of the mainsheet, one helluva challenge when you're up to your armpits in the cold ocean in ancient oilskins, and everyone is falling over everyone else. And as for suggesting the side-decks should be made wider, that would only make the cramped cockpit even more crowded. But with a skilled helmsman and an even more skilled mainsheet man, preferably of superhuman strength, it could be kept under control, for basically as our second picture shows, it wasn't an inherent fault in the shape of the boat which caused wild fluctuations in balance, but rather a severe temporary imbalance of the sails.

Under shortened rig of full main and jib, but with no tops'l or staysail set, this Dublin Bay 21 in a strong wind is showing marked but controllable weather helm, while the shape of her hull when heeled shows that it is inherently quite well balanced, without excessive fullness of the waterlines aft to distort steering characteristics.

Another topic which came up with the COS brigade (Crusty Old Salts) was the usefulness or otherwise of the topsails. A topsail is only as useful as the quality of its set, and if it isn't perfectly set up to become one with the main, then it can sometimes be worse then useless.

But as our final photo clearly shows, the luff of the Dublin Bay 21s tops'l was actually longer than the luff of the gaff mainsail. And it's the luff length that does the work in going to windward - it's worth remembering that in the great days of gaff rig racing with the big class, the top skippers were so certain of the need for luff length in windward ability that in heavy weather when they reefed the gaff mainsails, they then set up a jib-headed tops'l above the reefed sail in order to maximise luff length within the smaller sail area.

The luff of the jackyard tops'l in a Dublin Bay 21 was slightly longer than the luff length of the mainsail itself, so in sailing to windward, when luff length is at its most important, a well-setting tops'l made a significant difference.

But the problem with a topsail is that if it doesn't click perfectly into place at the first attempt, sometimes it takes for ever to get it right. So with the pace of life becoming more hurried as Ireland entered the 1960s, the time no longer seemed to be available to set up the complete Dublin Bay 21 gaff rig just to go out for an evening race, and the Howth 17s today don't permit topsails for evening club racing.

Back in 1963, when the Dublin Bay 21 crowd were arguing the merits of changing over to Bermuda rig, one of the points in favour of the change was the time it would save. That great sailor and Dublin Bay 21 enthusiast Cass Smullen said this was stuff and nonsense, and claimed he could set up the complete gaff rig of the Dublin Bay 21 in 25 minutes single-handed. So one of the boats was moored just in front of the National YC, and a crowd gathered, drinks in hand, to watch Cass take on the challenge. He did the job in 21 minutes. But they still changed to Bermuda rig.

BIBLICAL EPIC TO IONA

My apologies to Ivan Nelson (see comment at the end of last week's blog – Ed) for the ham-fisted use of English in discussing last week how a Kerry currach – a naomhog from the Dingle Peninsula – came to be sailing to Iona with the first bible in Irish for delivery to the sacred archives there. The bible was of course translated into Irish in 1602 (Old Testament) and again in 1680 (New Testament). We all remember it well. But somehow neither of these translations had ever found its way to Iona, so it was a first in that sense.

Anyway, it's thanks to the crew of Harry Whelehan's 32ft Sea Dancer out of Howth that we got to know of this Kerry voyage, which was done very low key, and in easy stages. Easy stages, that is, if you think it's easy taking a currach all the way up the west coast of Ireland and then past Malin Head and on to Iona.

The Kerry currach delivering the Irish bible to Iona last summer completed the voyage in true Christian spirit, with no designated skipper. Photo: Mark Tierney

It wasn't all swanning along under sail. In order to get from Ventry to Iona, they often had to pull with a will. Photo: Mark Tierney

The crew of Breanndan Begley, Anne Bourke, Danny Sheehy and Liam Holden did the voyage in three stages over three summers, and in such a spirit of Christian goodwill that the crew of Sea Dancer were unable to tell who if any was the skipper. But the Kerry folk did what they set out to do, then rowed around a few more Scottish islands before heading south, eventually getting to Wicklow. We look forward to hearing about their completion of the circuit of Ireland this summer.

NAOMH BAIRBRE HOME

Thursday nights won't be quite the same now. The six part series on TG4 by Donncha mac Coniomaire and his two shipmates (one of them his father Tomas) about their voyage along the Celtic seaways to Orkney southabout round Ireland from Connemara in the 47ft Galway hooker Naomh Bairbre has come to a successful conclusion. But it certainly shortened the winter watching this demanding ship and her engaging crew making their way to diverse ports which acquired added interest when viewed through the Irish Gaelgoir lens.

Mostly it drew pleasantly to a close as all good cruises do. But there were a few sad moments n the final epiode when they sailed up to Derry to pay their respects to the Galway Hooker An Lady Mor. Donncha had worked in a successful cross-community restoration project on this historic boat back in 2006, and the restoration team then sailed her from the Foyle to Connemara and back when the job was done. But now she lies abandoned and purposeless, ashore in Derry docks, deteriorating rapidly. She could be restored if somebody took action now – I can remember a successful restoration on the same vessel in the mid 1980s by Mick Hunt in Howth. Can't something be done now for An Lady Mor in Derry's year as City of Culture?

Can she be restored in the City of Culture? An Lady Mor, seen here being launched in Howth in 1985 after restoration by Mick Hunt, is urgently in need of restoration again, this time on the banks of the Foyle. Photo: W M Nixon

Comment on this story?

We'd like to hear from you on any aspect of this blog! Leave a message in the box below or email William Nixon on [email protected]

Recollections of Sailing & Swamping the Dublin Bay 21s

#dublinbay21 – Dun Laoghaire sailor and former Irish Sailing Association President Roger Bannon was intrigued by recent correspondence from Paddy Boyd to W M Nixon regarding the Dublin Bay 21s in his recent Afloat.ie Sailing on Saturday Column.

Here Roger recounts his first ever sail on the Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue in 1963 at the ripe old age of 11 and tells of his lifelong passion for sailing borne out of sailing these idiosyncratic elegant boats.

My own father was a regular crew on the Garavogue when she was owned by Des Dobson from the National YC and skippered by the irrepressible Sean Clune.

Paddy's recollections are pretty accurate. They were complete bitches of boats to sail, over-canvassed and fundamentally badly balanced. Their construction and design was also seriously flawed which meant that they constantly leaked and required endless expensive maintenance. They suffered from unbelievable lee helm which led to regular swamping's and indeed several sinking's.

It was very disconcerting in a squall that the boat would violently bear off, even with the sheets eased and bury the lee rail up to the coaming in the brine. While in this vulnerable position any wave coming over the bow would quickly flood the cockpit and create a dangerous situation.

Alfred Mylne came to Dublin shortly after they were built to have a sail. He was appalled at how badly they handled and subsequently submitted a report recommending that the location of the mast step and sail plan be altered to correct the problem. Needless to say the local owners decided that spending £200 was not justified and they ignored his recommendations.

The other shortcoming from which they suffered was the near vertical garboard plank which moved away from the hog when the rig was fully loaded which led to a constant ingress of water, which if not pumped out continuously, would lead to swamping in a very short time. The original steel floors had been badly designed and the rig loads were not properly dispersed throughout the hull. They were undoubtedly elegant but deeply flawed boats, largely because the original owners did not adopt the modifications specified by Mylne shortly after they were built.