Last week's Sailing on Saturday blog about the fate of classic yachts was a revelation about our readership. Although three significant historic vessels in three different and distant locations were involved, it was the news about the re-build of the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle which drew nearly all the attention. Cork Harbour may indeed be the true capital of Irish sailing, but the sheer size and wealth of the South Dublin population accessing the sea through Dun Laoghaire gives it special power and interest. As someone whose home port is outside Dublin Bay, W M Nixon happily returns to the fray.

It's little wonder that Ireland has won more than her fair share of Nobel Prizes for Literature, yet frequently has to look abroad when boats need to be built. We're great at working words into packages of merchandisable literature or high-flown arguments, but we're maybe not so good at building boats, or even looking after them.

But then, Albert Einstein was a keen sailing man, yet despite his intellectual genius, his boat was always a bit of a mess. So maybe it's all of a piece, that last weekend's story about – among other things – the re-build in France of a classic Dublin Bay 24 of 1948 vintage, has in the space of a few days evoked thousands of beautifully-crafted words in the comment section with enough heat generated to warm a small town. (to read comments scroll to the end of last Saturday's blog here – Ed)

Some of the big beasts of Dun Laoghaire's sailing jungle have enthusiastically thrown their hats into the ring, and already we can imagine some shrewd producer of Cable TV docu-dramas setting out a potential cast list for the likes of Roger Bannon and Hal Sisk, while the mysterious Michael Joseph will be played by The Man In The Iron Mask.

The irony of it all is that all these commentators aspire to the same thing – increased vitality and enthusiasm in Dun Laoghaire sailing. And sometimes, if they would take more time to read each other's detailed comments, they'll find they broadly are advocating the same methods of providing boats which will set the local sailing imagination alight, rather than being just another set of plastic fantastics.

But because of the Irish habit of "wanting nothing to do with that other crowd," a lot of creative diplomacy is needed to harness all this energy. Maybe an intense level of debate is unavoidable. For as we've said of another venerable Irish classic boat class which manages to survive and prosper, it does so by inverting the laws of physics, and relying on friction to create energy.

Let's begin with the most straightforward query – Michael Joseph's first question, posted on Wednesday 15th October, as to why do we think that the setup in Dun Laoghaire is not conducive to the preservation and continuing vitality of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, in other words the Dublin Bay 24s?

Well, basically it's because Dun Laoghaire has great difficulty in getting some of its acts together. It's physically a very fragmented sort of place. The relationship of the town with the harbour has always been problematical, and it's difficult to generate a general sense of maritime community which might be conducive to encouraging classic yachts which need to be well loved.

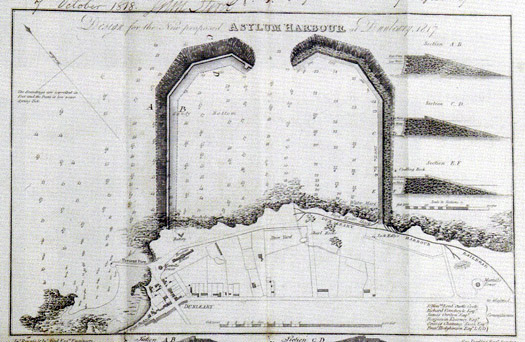

When the plans for the new "Asylum Harbour" were drawn up in 1817, it was seen purely as a shelter facility for shipping caught out in in adverse weather in the Dublin Bay. Although there was a tiny quay at Old Dunleary (the area is still known as The Gut), in the initial plan it was actually shown as being outside the new harbour. The thought that the crews of ships anchored in this new port of refuge might wish to have direct contact with the nearest bit of shore seems if anything to have been actively discouraged.

The proposed pans for an Asylum Harbour in 1817 did not include any suggestions as to possible in-harbour locations for jetties and quaysides, let alone waterfront development, and it actually excluded the small quay at Old Dunleary to the west, though in the final form the West Pier was moved further west to enclose the Old Dunleary pier.

This meant that when the inevitable shoreside facilities began to develop rapidly, it was all on a piecemeal basis. Ideally, when the plan for the harbour was finally agreed, a parcel of property of the same area as the harbour itself should have been secured on the waterfront for the planned development of a complete harbour town. But instead, you got opportunist growth - not really development at all. An unattributed quotation about 19th Century Kingstown, as it had now become, in David Dickson's recently published mighty tome Dublin (Profile Books) tells us much about the official view of the way things had got out of hand in the new seaside town, with speculative developers such as Mr Gresham from the Gresham Hotel putting up terraces of houses every which way:

".....no system whatever has been observed in laying out the town so that it has an irregular, republican air of dirt and independence, no man heeding his neighbour's pleasure, and uncouth structures in absurd situations offending the eye at every turn."

Ouch. For a growing conurbation which prided itself on being called Kingstown, that "republican air of dirt and independence" was a low blow. But as the new railway in 1834 had cut most of the new town off from the sea, an effect which was to become further emphasized by roads running parallel with it, the opportunities for dynamic interaction between town and harbour were restricted. Thus any waterfront space became too valuable to house the workshops of master craftsmen, boatbuilders and shipwrights who might be expected to be readily available to build and maintain local classes of wooden yachts of any significant boat size.

Modern Dun Laoghaire looking northwards, though it should be noted that this photo was taken before the contentious new library was forced into the waterfront between the Royal Marine Hotel and the National Yacht Club. With the water edge's almost exactly marked by the railway and the roads parallel to it, this clearcut division means that, far from the waterfront being part of a shared urban-harbour complex, the complete lack of planning in the early stages has resulted in very little comfortable inter-action between harbour and land, and there is precious little space available for locating specialist small boatyards and marine workshops which would facilitate the continuing good health of substantial wooden classic yachts.

So nowadays, the reality is that basing a cabin sailing yacht of any reasonable size in Dun Laoghaire on a year round basis is too expensive already without the added cost of her being a high-maintenance classic. The best value for money in Dun Laoghaire at the moment is probably provided by a Sigma 33 or a First 31.7 raced as a One Design. Yet in both cases, the necessary membership of one of the waterfront yacht clubs and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, added to the expense of a marina berth and the most basic running costs, means an owner-skipper is shelling out around €10,000 per annum before anything much has been done with the boat.

So although Dublin Bay Sailing Cub works wonders in co-ordinating the racing of hundreds of boats, the survival or otherwise of a class is dictated not by policy decisions on promoting new classes by DBSC, but rather by ruthless market forces, with the sheer expense of sailing from Dun Laoghaire dictating which classes can hang on when times are bad.

The result is that over the years, the surviving classics have become steadily reduced in class numbers, and only the smallest boats survive. With the loss this year of the 17ft Mermaids as an officially recognized Dublin Bay class, as they could no longer guarantee the minimum fleet of five boats, only the 25ft Glens survive from the former serried ranks of several wooden keelboats, and only the 14ft Water Wags survive of the once numerous wooden dinghies.

Yet the growing health of the Water Wags – which can trace their history back to 1887 as the world's first One Design Class - suggests that even in the cut-throat accountancy-led world of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, people still have a natural fondness for classic wooden boats. The current fleet of robust Water Wag dinghies are to a design adopted in 1904, and it adds to their attraction that although they were supposedly designed by local boatbuilder James Doyle, it's generally agreed that the real designer was his talented daughter Maimie.

Mind the gap........ Some of the fleet of a dozen and more classic Waterwags which departed their home waters of Dublin Bay last weekend to race in County Roscommon on the North Shannon's Lough Boderg. Photo: Guy Kilroy

The class have an instinctive sense of their own community, with mutual assistance in maintenance and honing sailing skills a natural part of the healthy mix. One of the factors which has increased their viability is the huge improvement in boat road trailers, for although they remain firmly based in Dun Laoghaire, from time to time you find they've upped and left and gone off for a weekend's racing at some strange and distant location, which might well be described by the management wonks as a bonding exercise

Last weekend, they were having their annual North Shannon Regatta. One of the keenest owners, Guy Kilroy, has a farm in Roscommon on the west shore of Lough Boderg, and the Water Wags descended on him in force. Despite the presence of the great Jimmy Furey building his classic sailing dinghies at Leecarrow on the west shores of Lough Ree, you'd never have thought of Roscommon as a sailing county, but there you go. However, while the coastal Autumn leagues at Crosshaven and Howth saw the seasonal mists soon dispersed, on Boderg in the middle of Ireland it took a long time for the fog to lift. But when it did, the sailing was sublime, and they got in two good races, with four boats level on points, but Ian and Judith Malcolm in the 99-year-old Barbara won on the countback.

Wags-in-a-mist. While the seasonal mists soon cleared at the Autumn Leagues on the coast at Crosshaven and Howth, in the heart of Ireland on Lough Boderg the fog lingered. Photo: Judith Malcolm

Lots of TLC. They may be in the reeds, but the maintenance mustn't be done in a rush.....The high standard of TLC on the Water Wags – the oldest chime in at 110 years – is a wonder to behold. Photo: Ian Malcolm

When all the loving care becomes worthwhile – perfect racing on Lough Boderg last weekend for David McFarland's Moosmie (15) and Vincent Delany's Pansy (3), with Killian Skay's Maureen (29) and Scallywag (44, David Williams and Dan O'Connor) in gentle pursuit. Photo: Guy Kilroy

Maintaining a Water Wag is a very manageable business, but inevitably as the recession recedes, there'll be noises about reviving larger wooden classics, and there's a feeling that the Mermaids aren't completely finished in Dun Laoghaire harbour just yet. There was an interesting twist to this in 2014's Mermaid racing, as the National Championship at Rush was won by Jonathan O'Rourke of Dun Laoghaire's National YC.

Despite being up in Fingal's Rogerstown heartlands where in recent years they've built some supposedly hyper-competitive Mermaids with the clever use of epoxy, Skipper O'Rourke's boat is the 1960 Grieves Brothers built Tiller Girl, which is surely a hopeful sign for the class's future.

The age-defying champion. Mermaid Champion 2014 Jonathan O'Rourke (National YC) with his 1960-built Grieves Brothers boat Tiller Girl. Despite there currently being no racing for Mermaids in Dun Laoghaire, Tiller Girl won the Nationals at Rush even though she was in the area where new supposedly lighter Mermaids, using the exoxy wood system, have recently been built. Photo: W M Nixon

Well, hello Dolly! Named after the world's first cloned sheep, the cloned GRP Mermaid Dolly (white hull) was built in the hope of revitalizing the class, particularly in Dun Laoghaire. But even though she only had a fiberglass hull shell with the rest of her – including the mast – in wood, the new concept was rejected by the class. So Dolly is now based at Sag Harbor in the Hamptons on Long Island in America, where she is much admired, while three of her sisters have proven very to be very durable and effective training boats at a sailing school in West Cork.

Nevertheless, it's at this time of the year that the hassle of maintaining a clinker built wooden boat comes centre stage yet again, and I have to confess that when Roger Bannon produced the fibreglass-hulled Mermaid Dolly, I thought she was a super boat and still do, but the class elders decided otherwise.

Moving on up the size scale, we return to the battleground of the Dublin Bay 21s, still mouldering in a Wicklow farmyard. I only once sailed on one of them under their classic gaff rig complete with jackyard topsail, and despite the enormous spread of cloth, was very impressed by how light and responsive they were on the tiller, but then we were racing in a gentle breeze.

The Dublin Bay 21s await their fate in a Wicklow farmyard

However, this constant refrain about them acquiring dangerous lee helm in strong winds seems to me to be a result of the primitive mainsail arrangement, with the tail of the mainsheet led directly from the counter to cleats on the cockpit coaming. This gave very poor levels of sail control in squalls, and often when the helmsman requested that the mainsheet be quickly but carefully eased to give him better control and keep the boat more upright, it would instead be let go with a run, the mainsail would then be flogging out of control, the close-sheeted headsails would force the bow off, the end of the long mainboom would then hit the water causing the sail to fill with the boat now on a reach, and over and under she'd go.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

So it could well be that if a re-built class of Dublin Bay 21s ever emerges, that then they might be given an added safety factor by having the mainsheet led forward, guided close along the underside of the mainboom, and then come down the aft side of the mast to be controlled by a winch on top of the coachroof.

As to whether or not we'll ever see the 21s race again, the odd thing is I think this week's intense exchange here on Afloat.ie may have brought it all a bit nearer. Because if you plough on through the icy politeness of the initial exchanges between Hal Sisk and Roger Bannon, I think you'll discern that they both reckon a cold moulded multi-skin timber hull construction to be a very viable option.

Roger Bannon points out that building a completely new hull on the ballast keel of the original boat is recognized under maritime law as being the continued existence of the same boat, which somehow is an oddly heartening bit of information when you look at the utter dereliction of the DB 21 hulls today.

Could this be the future for the Dublin Bay 21s? Beautiful multi-skin construction under way on Steve Morris's 32ft Harrison Butler designed classic at Moyasta near Kilrush. If it's adopted for the revival of the Dublin Bay 21s, as several of the boats would be buit in one batch construction could be facilitated by the inverted hulls being built on a male mould, thereby making the work easier for newcomer to boatbuilding working on a community basis.

Photo: W M Nixon

And as for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra, they've been considering seriously the work being done by Steve Morris near Kilrush in building a cold-moulded classic cutter to Harrison Butler's Khamseen design. Steve was the lead builder in constructing the superb gaff cutter Sally O'Keeffe down in West Clare. So when you see his work on his new boat, all things seem possible, particularly if it's agreed that the new Dublin Bay 21s should be cold-moulded in multi-skin timber on inverted hulls in a maritime community project in Dun Laoghaire, as the basic work would be relatively unskilled, and everyone could have a go at it.

For, as the success of the wonderful CityOne dinghy project in Limerick has shown, in sailing the building of the boat can be as much part of the experience as the subsequent time afloat. But if we ever do see the Dublin Bay 21s sailing again, let it please be with the proper rig. Everyone seems to be pussy-footing around the idea of a more easily handled semi-gunter configuration, maybe with just one jib. What's the point of all that? This isn't meant to be Easy Street. Let's have the full jackyard tops'l and cutter rig and all the bells and whistles, or let's not bother at all.

Should the Dublin Bay 21s be re-built, it has been suggested that for ease of handling and project management they might in future use this simpler "American gaff" rig, as seen here on Zanetta which was built on the Clyde in 1918 to the Dublin Bay 21 design.............

,,,,,but here at Afloat.ie, we reckon that would be the wrong approach. If you're going to have a new Dublin Bay 21, then she should have all the classic bells and whistles and more sail than is good for her, just as we see here with the Ringsend-built Innisfallen having a bit of sport with her spinnaker in the 1950s.