The story of the historic 1926-built trading ketch Ilen, and her recent return in her restored state to the Shannon Estuary and Limerick, has evoked many memories writes W M Nixon.

But few if any of these stories are as special as those shared by the McCarthy family of Cork, whose interest was spurred when Ilen was re-launched. This inspired a heartfelt personal Facebook post by Paul McCarthy, manager of the Firkin Crane Dance Theatre in Cork, and with his permission, we publish it here:

Bursting with pride I was. Bursting with pride. The TV news report was about the launch of a boat called the Ilen in Baltimore harbour in West Cork. The boat had been refurbished locally by passionate enthusiasts, their passion emanating from a legacy laid down when the boat was originally built in Baltimore in 1926 and sailed, by brave West Cork seafarers, all the way to the Falkland Islands, 7,000 nautical miles, straight down the globe, next stop Antarctica. The Ilen would be, for the next 70 years, a supply vessel connecting the Islands. In the1990’s, ready for the junkyard, the Ilen was rescued and transported back to Cork to be restored to her original splendour.

For me, seeing the Ilen for the first time was quite an eye-opener. Like seeing in glorious colour what had only always been available in black and white. Have you ever told something to someone and you know they are impressed but you also know in your heart they don’t have the full picture? Now I realise how my dad must have felt because I had no idea the boat he had been telling me about, was just, so, small.

My dad Patrick McCarthy was an engineer in the Royal Navy between 1939 and 1961. He left Bantry looking for work in Liverpool and enlisted just before the breakout of World War 2. His passion was mechanics, and the Navy provided the opportunity to learn all there was to know about engines. We’ll put aside his WW2 exploits during the Artic and Atlantic Convoys and the Italian and Normandy Landings, because this story is about the good ship Ilen in peacetime, in 1952.

The Falkland Islands are located in the Southern Atlantic 300 nautical miles from the mainland of Argentina. Claimed by Britain, contested by Argentina, the nearest friendly mainland was, and still is, Chile, 700 nautical miles away and around Cape Horn, the most treacherous sea passage in the world, where the Pacific and the Atlantic constantly clash heads.

As a British overseas territory exposed to invasion from Argentina, there was the need for a constant military presence entailing at least one Royal Naval ship at anchor in Port Stanley. In 1952 my dad was the chief engineer on one of those visiting ships on guard duty, the frigate HMS Veryan Bay.

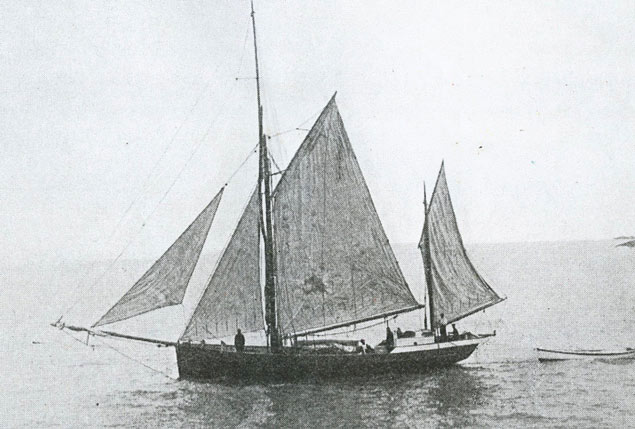

The 56ft Ilen as she was when Conor O’Brien, crewed by Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear Island, sailed her out from Ireland to the Falklands in 1926

The 56ft Ilen as she was when Conor O’Brien, crewed by Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear Island, sailed her out from Ireland to the Falklands in 1926

The Ilen by this time had seen 25 years in service bouncing around on the often-foamy waters between the islands. She was in need of a serious overhaul and the nearest facilities were in Punta Arenas in southern Chile, 400 miles straight across the wild open ocean that is the South Atlantic. The regular crew of the Ilen were not seafarers or engineers, and so would not risk the long journey. On a regular basis the Governor of the Island, Sir Geoffrey Miles Clifford, would welcome the newly visiting Navy ships and, usually invited to dinner in the officers’ mess, he would explain about the plight of their local supply boat and enquire if anyone aboard might be able to help. The answer was always no. That was until my dad’s ship arrived. That night at dinner the Captain put the message out around the ship to see if anyone would volunteer to help. Guess who knocked on the door of the officers’ mess? ‘What do ye need?” offered Dad in his never diluted Bantry accent.

The following day he went aboard the Ilen with Sir Geoffrey and looked over the engine, started her up, listened, and turned to the Governor and said he was sure he could keep her going long enough to make the crossing. Sir Geoffrey beamed: “You must come to dinner tonight, I want you to meet my wife and family and we can discuss the practicalities. Thank you so much, Pat. I have gone aboard numerous visiting ships up to now, and no one has offered to help. And the Islanders thank you.”

At dinner that night in the Governor’s Mansion, while his shipmates settled for standard ship’s fare, Dad was treated like a hero. They discussed the route options and they agreed the safest route would be through the Magellan Straits which are named after the great explorer Ferdinand Magellan who, when failing repeatedly to bring his own ship around the ferocious seas off Cape Horn, sought out this inland route inside the tip of South America.

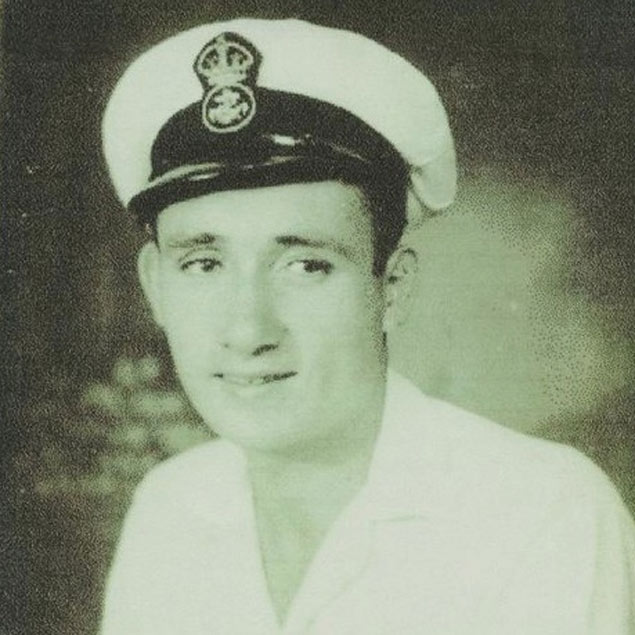

Pat McCarthy in his days as a ship’s engineer

Pat McCarthy in his days as a ship’s engineer

None of the regular crew would agree to the trip, they were after all part-time sailors, mostly farmers, who manned the Ilen whenever supplies needed to be moved between the islands. The Governor said the crew would be made up of a group of five local whaler fishermen, who had sailed the southern oceans crewing other whaling boats. They had saved up enough money to purchase their own boat in Chile, and so agreed to crew the Ilen to Punta Arenas in exchange for free passage. Dad slept in a bedroom that night in style and comfort far removed from his bunk on the Veryan Bay.

Following breakfast the next day, he headed back down to the port and reporting on board his own ship, he explained the situation to the Captain who released him to make his own way to Punta Arenas where they would rendezvous. The Veryan Bay would sail the 700 nautical miles around Cape Horn while Dad and the Ilen would take the more direct route through the Straits, too shallow and narrow in places for the big ship.

I remember asking Dad what the others on his ship thought of his plans, and he just shrugged his shoulders, “It needed to be done and I could do it. I knew the engine, and plus they knew I spent the war volunteering for everything that came my way, so this was no different.” On another occasion, over a pint with my dad, he revealed that his habit of volunteering early on in the war resulted in lucky escapes on at least two occasions when the ships he departed for volunteer duties had subsequently been sunk in battle, one with all hands lost, so he considered volunteering a natural, positive twist of fate that was being sent his way.

A few days later, while Dad was meeting with his fishermen crew and going over the workings of the Ilen, the Veryan Bay disappeared over the horizon. He was now on his own, an honorary Falkland Islander. They spent several days preparing the boat for the voyage they estimated should take 4 days if the weather held.

It was a fine Friday morning when they motored out of Port Stanley leaving the Governor, his family and a smattering of Islanders on the quayside wishing the gallant men bon voyage. Dad was at the helm and having carried out a rudimentary service on the engine, he was confident she would deliver them safely through the Straits. But before the Straits, there were those 300 miles of open ocean.

A very exposed part of the world. The Ilen’s passage from the Falklands to Punta Arenas in Chile would have been challenging even if she had been in first class order

A very exposed part of the world. The Ilen’s passage from the Falklands to Punta Arenas in Chile would have been challenging even if she had been in first class order

It was on Saturday the weather began to change. With the wind gusting from the south, and waves growing in stature, the direct westerly line of navigation had to be abandoned in favour of a zigzag pattern, to avoid being hit broadside by the waves and weather. This more than tripled their rate of progress through the water and the number of days exposed out at sea. The foul weather continued unabated for the next 24 hours and the constant changing of direction was putting an undue strain on the ailing engine.

The darkness delivered even greater danger and required all hands on deck to scan the black horizon for incoming waves. It was a blessing that the engine lasted until dawn. But with the dawn came spluttering and then silence. Dad belted below as one of the crew took over the wheel and the others frantically raced to hoist the sails. Dead in the water in these conditions, she would be knocked over within minutes unless they regained control and direction.

They were now 160 miles from the relative shelter of the Straits and without engine power, under sail relying on the wind alone. Fortunately, the crew were competent seamen and had a fair bit of experience in these waters under sail, but that was in boats designed for heavy weather and with much larger crews. Still, they kept her off the wind and as steady as possible while Dad worked on the engine below. At one point, he recalled, one of the crew appeared by his side offering to help. Dad was grateful for a while but soon sent him back up as he was only getting in the way. I know from personal experience that my dad had exacting standards, and a short temper when things are not going as planned, so the young crewman would have been much safer on deck.

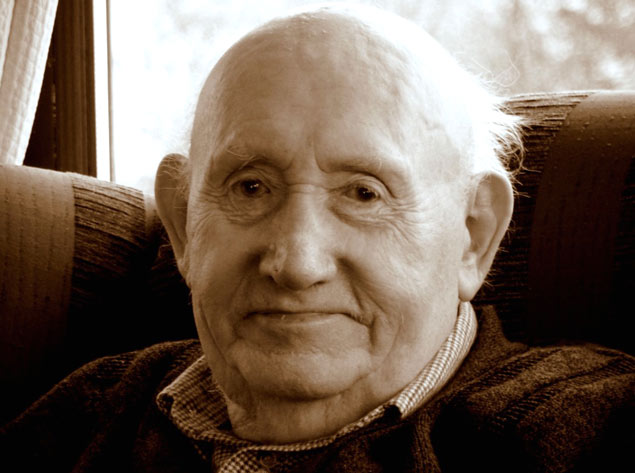

A man with a fantastic store of memories - the late Pat McCarthy in his retirement home in Cork

A man with a fantastic store of memories - the late Pat McCarthy in his retirement home in Cork

He remembered being tossed about like a rag doll in the engine compartment, sometimes using lengths of strapping, normally used to secure cargo, to tie himself into position while he dismantled the engine looking for the problem. After hours below, he could not remember or was not counting how many hours. As he began to reassemble the engine, he became aware of the increasing violence of the rolling from side to side, and the brute force of the waves crashing over the boat. The storm was getting worse. Then, a crewman rushed below to tell him the sails were blowing out and he should get ready to come up top or be trapped below if they sank. He stayed where he was. He knew he was almost there. Soon after, just as it was getting dark, he restarted the engine. It sounded good. It would hold. He clambered up onto the deck and took the wheel from the sailor who joined his mates pulling in and tying down the remaining sails. He turned the Ilen into the wind and gauging just the right amount of throttle, rode out the remainder of the storm.

With the sun rising on their backs they could just make out the shape of land ahead. By lunchtime, they were scrutinising the charts to find the narrow inlet that was their entrance to the Magellan Straits. Through the next night, they motored gently through the channels. Huge cliffs sometimes closing in on them, and at other times it was wide inland waterways, often as rough as the oceans outside. Dad explained that whatever about the danger of the open ocean this was even more treacherous because if the engine failed again they would be blown into the cliffs for sure.

HMS Veryan Bay was a Bay Class Frigate, in commission from 1945 to 1957

HMS Veryan Bay was a Bay Class Frigate, in commission from 1945 to 1957

Arriving at Punta Arenas, the HMS Veryan Bay was waiting. A small party of Dad’s navy crew came aboard the Ilen to welcome the adventurers ashore with fresh food and some beers. The Islander crew, to demonstrate to the navy sailors how close to disaster they had come, unfurled the sails to reveal mostly shredded canvas. My dad recalled the feeling in the pit of his stomach, It had been getting dark when they were stowing the sails at sea, and he had no idea at the time that all that was left was shredded canvas. All agreed it was a miracle that they stayed afloat in such a storm with so little sail, but the hero was the man who would not give up and got the engine running just before the last piece of sail blew out.

Dad left the Navy in 1961, the year I was born. He told me that story many times over the years, usually over a pint after his retirement, but most recently in the nursing home where he passed away only two years ago. I knew the story by heart but not until I saw the footage of the Ilen on TV, the actual boat, all 56 feet of her, did I grasp the magnitude of that achievement. Bursting with pride I am, bursting with pride.

In Memory, Patrick McCarthy, Born 28th September 1920, died 2016.

President Michael D Higgins with Paul McCarthy at a recent event in the Firkin Crane Theatre in Cork.

President Michael D Higgins with Paul McCarthy at a recent event in the Firkin Crane Theatre in Cork.