Displaying items by tag: Saoirse

Conor O’Brien’s World–Girdling Saoirse Will Sail Again

The process towards re-creating Conor O’Brien’s famous Baltimore–built 42ft ketch Saoirse, in which he gained his place in international sailing’s Hall of Fame with the first circuit of the world by a small vessel south of the great capes in 1923-1925, has been quietly confirmed this week with the agreement of a well-resourced backer who for the moment prefers to remain anonymous. W M Nixon takes a fresh perspective on one of Irish sailing’s central stories.

Much and all as there was triumph and tribulation and then triumph again in Conor O’Brien’s sailing achievements, his personal life could be summed up as one of success and sadness. So could many lives. But as with most things to do with Conor O’Brien, success and sadness came on an epic scale – there was a monumental, sometimes tragic quality to it.

It is something which is inevitably going to receive more attention as the process of re-creating his remarkable little ship swings into action in Oldcourt near Baltimore. The Saoirse re-build is coming centre stage in West Cork as the great and lengthy project of re-building his 57ft 1926 ketch Ilen nears completion. Ilen will be launched next summer, and the quality of the workmanship of Liam Hegarty and his craftsmen in Oldcourt with this project will achieve the recognition it so richly deserves.

So too will the vision of Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick who inspired Ilen’s re-birth, which in turn has provided the credentials to make the re-creation of Saoirse something which is becoming very real. It has become so real that the new keel has already been cut and shaped, while enough bits and pieces have been retrieved in Jamaica from the wreck of Saoirse in her first incarnation to provide a real connection for the re-born boat. Meanwhile, next week will see the orders being placed for further consignments of the required timber.

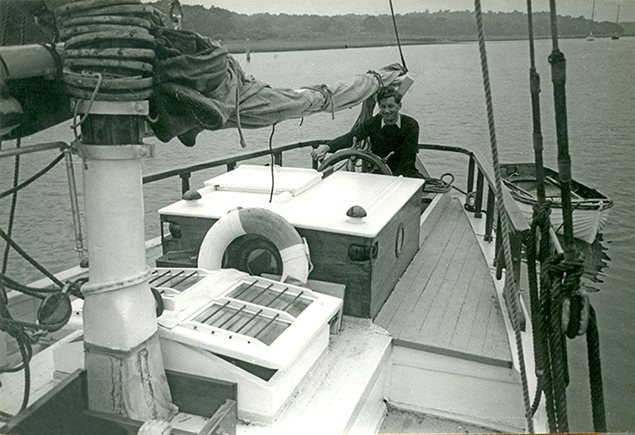

Conor O’Brien was at his most content when up in the mountains, or far out at sea. He is seen here at the helm of Saoirse in mid-ocean as she reels off the miles in her famous effortless style. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien was at his most content when up in the mountains, or far out at sea. He is seen here at the helm of Saoirse in mid-ocean as she reels off the miles in her famous effortless style. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The very idea of some day being able to sail on an exact replica of Saoirse, a replica which has retained the soul of the original vessel, is something which will fascinate anyone who has made even the most cursory study of what O’Brien achieved on his voyage, and in his design of this unique boat.

There are probably many more in Ireland who are tangentially aware of O’Brien through the fact that, with the ketch Kelpie, which he owned from 1911 to 1922, he was the junior partner with Erskine & Molly Childers’ Asgard in the gun-running to Howth and Kilcoole in 1914, with Kelpie’s cargo of 600 Mauser rifles being taken for the final stage to the Kilcoole landing aboard Sir Thomas Myles’ auxiliary-powered Chotah. But in terms of the world’s amateur sailing history, the 1914 gun-running pales into insignificance when set against the mighty circumnavigation of the little Saoirse in 1923-25.

It was the first major international voyage undertaken under the ensign of the new Irish Free State. Yet despite the new tensions which inevitably existed between the British establishment – particularly the British maritime establishment - with the nascent Irish state and those who created it and ran it, it was a pillar of the British maritime establishment who set the international tone in putting Conor O’Brien’s voyage with Saoirse in its proper and revered context.

These days the name of Claud Worth will only be known to those who are immersed in the details of the history of cruising and its development. But in the first thirty years of the 20th Century, Claud Worth – ophthalmic surgeon by day, seagoing guru for much of the rest of the time – was an authority in a league of his own.

A kindly authority, let it be said. And always a source of helpful advice, with suggestions which are still relevant today. Just recently, someone asked about how best to prepare a log for a cruising competition. The most useful response was to quote Claud Worth’s suggestions from 1910 about how you should gradually introduce the boat, her crew and the planned cruise as the story unfolds, to bring the reader along with you to share the experience, rather than have it hurled at them as a mass of indigestible statistics about mileages, wind strengths, and dealing with problems large and small.

Thus by the time Saoirse set off on her voyage, Claud Worth was the global authority in the world of log adjudication, and he found himself in the demanding position of assessing logs for the world’s senior cruising trophy, the Challenge Cup of the Royal Cruising Club.

This had been awarded on its inauguration in 1896 to Belfast doctor, Howard Sinclair, for a cruise round Ireland in the 6-tonner Brenda. But by 1923, the scope of the several major cruises put forward for the Challenge Cup had expanded enormously from round Ireland voyages. Yet in his adjudications, Claud Worth unhesitatingly awarded the Challenge Cup for 1923, 1924 and 1925 to the former gun-runner as Saoirse’s voyage round the world went on to various ports, through the Great Southern Ocean, and back into Dun Laoghaire exactly two years to the day since he first departed on what had been casually described as “a voyage to New Zealand for some mountaineering”.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire in June 1923 at the start of her voyage. Photo Irish Times In fact, so clearcut had Worth been in his analysis that he provided the Introduction for Conor O’Brien’s entertaining if sometimes eccentric account of Saoirse’s circumnavigation, the timeless sailing classic Across Three Oceans. Claud Worth’s foreword has so much insight that it continues today to be the final word on the voyage, and in a few pithy comments he sums up what had been achieved by the 42ft ketch to O’Brien’s own design, and built in fishing boat style by Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire in June 1923 at the start of her voyage. Photo Irish Times In fact, so clearcut had Worth been in his analysis that he provided the Introduction for Conor O’Brien’s entertaining if sometimes eccentric account of Saoirse’s circumnavigation, the timeless sailing classic Across Three Oceans. Claud Worth’s foreword has so much insight that it continues today to be the final word on the voyage, and in a few pithy comments he sums up what had been achieved by the 42ft ketch to O’Brien’s own design, and built in fishing boat style by Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore.

“Mr O’Brien’s plain seamanlike account is so modestly written that a casual reader might miss its full significance” wrote Worth. “But anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds from 150 to 170 miles per day, as well as handling the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered”.

The voyage completed, the energetic and sometimes impatient O’Brien was busy with fulfilling the contract he’d brought home with him to build the Ilen to be the Falkland Islands freight and passenger ketch, and with writing his book. Once the latter had appeared, his celebrity was assured, and he was persuaded to enter Saoirse in the 1927 Fastnet Race.

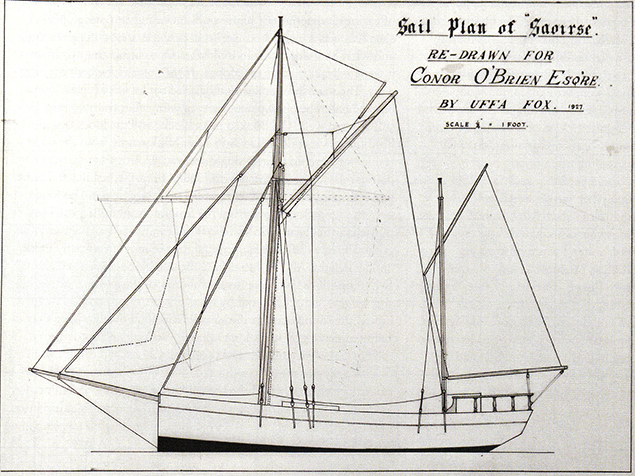

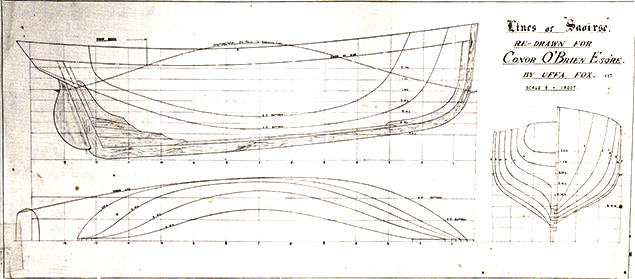

There was much windward work as soon as the fleet had left the Solent, and no-one in the crew disagreed when he eventually withdrew, as he’d re-rigged Saoirse as a sort of mini brigantine, and windward work definitely wasn’t her strong suit. But it had by no means been a wasted expedition, for in Cowes before the race, designer Uffa Fox took off Saoirse’s lines. O’Brien - an architect by training - may have designed her himself, but many of his drawings were distinctly free-form, so now that Saoirse is going to be re-created, the precision of Uffa Fox’s work is going to be invaluable in getting once again the exact shape of “this little bluff-bowed vessel”.

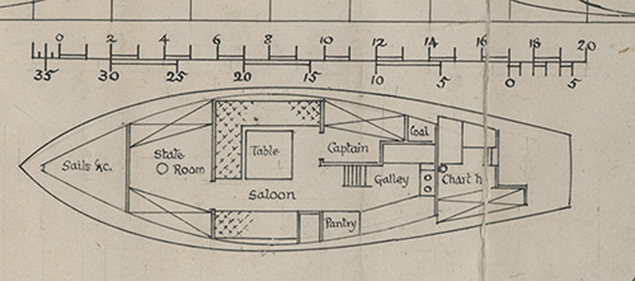

Saoirse’s accommodation - Conor O’Brien’s personal drawings. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s accommodation - Conor O’Brien’s personal drawings. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

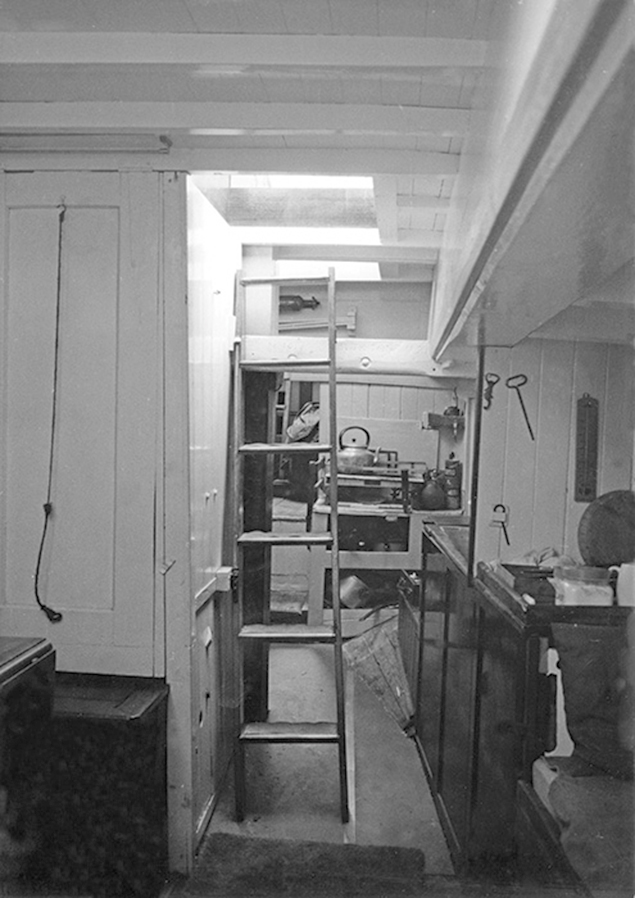

The homely comfort down below. Conor O’Brien may have used old-fashioned concepts in creating Saoirse, but he was well ahead of his time in placing the galley down aft in the position of least motion. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The homely comfort down below. Conor O’Brien may have used old-fashioned concepts in creating Saoirse, but he was well ahead of his time in placing the galley down aft in the position of least motion. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

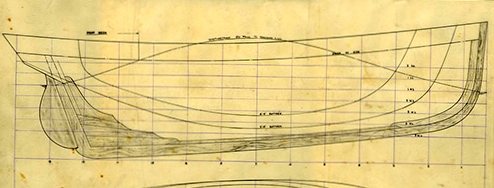

Saoirse’s hull and sailplan profile as recorded by Uffa Fox in 1927. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull and sailplan profile as recorded by Uffa Fox in 1927. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

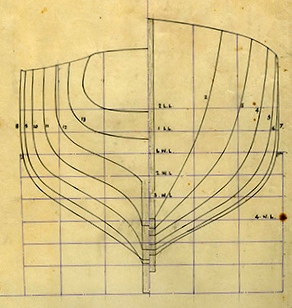

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927 Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927 Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

As the 1920s drew to a close, Conor O’Brien was at something of a loose end. Of a land-owning family in West Limerick, his expected inherited income had shrunk with the effects of the various Land Acts which had started in the year of his birth, 1880. It was a situation of which a part of him approved, yet he could be such a prickly individual that he never functioned comfortably in the committee situations which his speciality as an ecclesiastical architect required him to work, and thus his earning levels could be precarious

He was uncompromising in his approach to anything and everything. Saoirse was a complete statement of his wish to have a simpler world in which every item was attractively functional. She was the seagoing expression of his enthusiasm for the purest tenets of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement. It will be intriguing, when she is reborn, to see if she really is as comfortable as it appears in the drawings and photos. These seem to suggest that she’s the sort of boat it’s a pleasure to be aboard for extended periods, and you will definitely be in her rather than on her - she is a a proper little ship, a world of her own.

Conor O’Brien and Kitty Clausen O’Brien hoisting sail on Saoirse with a chain halyard. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien and Kitty Clausen O’Brien hoisting sail on Saoirse with a chain halyard. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

It was a world O’Brien needed to share with someone special, and miraculously he found that someone with Kitty Clausen. Of an artistic family, she was nevertheless a practical person who was one of the few people who could make Conor O’Brien content, for in his world voyage his impatience with the short-comings of others meant that, in all, Saoirse carried something like 18 different crewmembers before she finally returned to Dun Laoghaire.

Conor and Kitty were married in 1928, and by 1931 a new and mellower Conor O’Brien had emerged as they sailed a slightly more domesticated Saoirse to the Mediterranean. There, they found the then little-known Balearic Island of Ibiza to be a congenial base where Conor continued writing books, and Kitty provided the illustrations. It was an idyllic existence, and their pleasure in it was reinforced by any return visits they made to the Ireland which was emerging after Independence, for they found it an oppressive place far indeed from the idealism of those who, like Conor O’Brien, had actively supported Home Rule.

The good times. Aboard Saoirse approaching the Spanish coast during the early 1930s, when Conor and Kitty cruised the Mediterranean. In this photo, Saoirse is setting the mini-brigantine rig which O’Brien created using her existing masts in 1927. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The good times. Aboard Saoirse approaching the Spanish coast during the early 1930s, when Conor and Kitty cruised the Mediterranean. In this photo, Saoirse is setting the mini-brigantine rig which O’Brien created using her existing masts in 1927. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

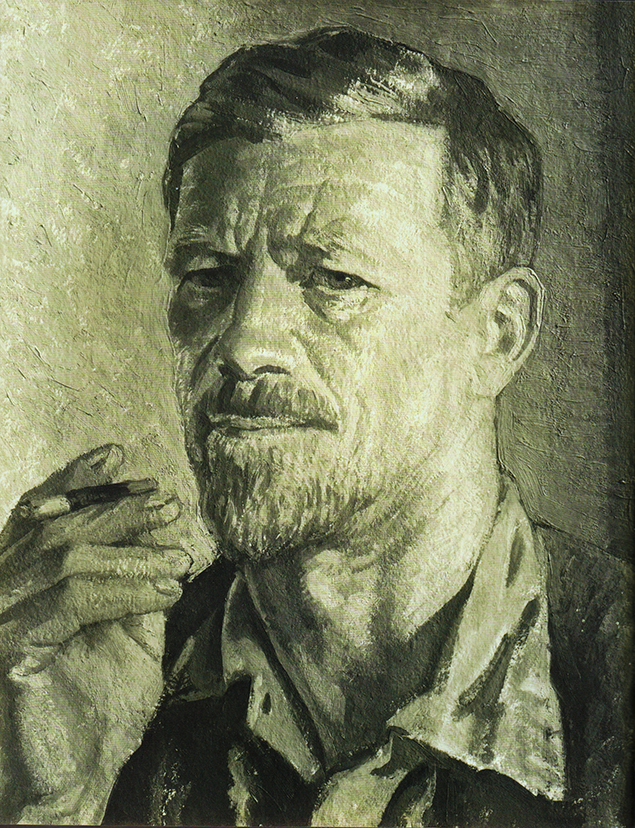

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by Kitty Clausen. Courtesy O’Brien family

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by Kitty Clausen. Courtesy O’Brien family

Thus when they sailed north they tended to go to Falmouth in Cornwall, with their base at St Mawes on the east side of that fine natural harbour. However, cruises to the south continued - they were in the Greek Islands in 1934, and by February 1935 they were wintering in Vigo in northwest Spain. But Kitty’s health was deteriorating, and they returned that summer to St Mawes. She died of leukaemia in 1936, aged 50, and was buried nearby at the waterside church of St Just-in-Roseland.

Conor O’Brien wrote little of her death and what it meant to him, but for some time, his life lost all purpose. He’d lost the urge to cruise Saoirse, and had her hauled in the boatyard across in Falmouth, where he lived a hermit-like existence on board. Then the outbreak of World War II brought him back to life. Like all the gun-runners in 1914, he’d immediately gone into action with the British forces in World War I, serving on mine-sweepers in the North Sea. But on the outbreak of World War II in 1939, with his age now approaching 60 he became involved with the Admiralty Ferry Service, delivering American-built naval and military vessels across the Atlantic.

Aboard Saoirse during the Ruck family’s ownership. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Aboard Saoirse during the Ruck family’s ownership. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse in Dun Laoghaire during a cruise to Iceland in 1974. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse in Dun Laoghaire during a cruise to Iceland in 1974. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

While in America, in 1941 he got an offer which he accepted from Eric Ruck to buy Saoirse in Falmouth. Ruck and his family were happily to continue owning this eccentric but very loveable vessel until the late 1960s, following which she had two owners, one of whom brought her to Ireland in the mid-1970s during a voyage to Iceland, while the other then sailed her across the Atlantic and lost her on a Jamaican beach in heavy weather in 1979.

But for Conor O’Brien, from 1945 onwards after the excitement of World War II, life trickled away. He retreated to a cottage on Foynes Island in the Shannon Estuary, and while he joined family on the island for meals, his was a solitary existence, though visits to “nearby Ireland” could occasionally result in unexpected conviviality.

He died in 1952, aged 72, in a world and in an Ireland very different from the high hopes of the 1920s, when a little ketch had set out from Dublin Bay to celebrate the establishment of a newly independent Ireland. In doing so, she was to make one of the greatest voyages of all time, a pioneering achievement which was publicly recognized at the time.

But by the depressed 1930s, people had other things on their mind, and by the 1950s when Conor O’Brien died, it was largely forgotten outside the circles of dedicated cruising enthusiasts.

Yet time heals, and changes our perspective. The voyage of the Saoirse is now more widely acknowledged than ever as an exceptional seafaring achievement, as is the special genius of Conor O’Brien, and the re-creation of Saoirse is the greatest tribute which can be paid to him.

As for the woman who brought him true happiness for a cruelly short time, it was many years ago that we first visited the sailing enthusiast’s church of St Just-in-Roseland on the east side of Falmouth Harbour. But it was only more recently that we learned that Conor O’Brien’s wife is buried there, under a giant pine tree. Her grave is marked by a simple headstone, designed by her husband in his signature style. It is a peaceful place.

The parish church of St Just-in-Roseland on the eastern shore of Falmouth Harbour. Kitty Clausen O’Brien’s grave is at the foot of the giant pine tree on the right.

The parish church of St Just-in-Roseland on the eastern shore of Falmouth Harbour. Kitty Clausen O’Brien’s grave is at the foot of the giant pine tree on the right.

The simple headstone, designed by Conor O’Brien. Photo: W M Nixon

The simple headstone, designed by Conor O’Brien. Photo: W M Nixon

#woodenboats – In the annals of Irish seafaring, whether professional or amateur, only a very few can match the achievement of Conor O'Brien (1880-1952). Between 1923 and 1925, this multi-talented sailor from Foynes on the Shannon Estuary circled the world south of the Great Capes in the 42ft ketch Saoirse which he'd designed himself with the help of Tom Moynihan of the Baltimore Fisheries School Boatyard.

It was there that this unique vessel was built in 1922-23 as Ireland in general – and West Cork in particular – recovered from a short but brutal Civil War. The very fact that Saoirse was built in Baltimore, followed by the successful completion of her great voyage, became part of the slow post-war healing process. So as the 2015 Traditional and Classic Boat Season gets under way this weekend with the Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival, W M Nixon voices the hope that Saoirse – which had been feared totally lost since 1979 – may be re-born.

They're hardy sailors in West Cork. That lotus-land of easygoing cruising may seem a gentle place in high summer, yet down there they've felt the recent summer-delaying cold spell as sharply as anywhere else. But despite the unfavourable conditions, as usual in this last full weekend of May we'll see the Baltimore Woodenboat & Seafood Festival swing into action. And although wooden boats need reasonably good springtime weather almost as an essential for the annual refit, there'll be a colourful turnout of character vessels large and small.

But the talk of the town will not be about a boat which is showing her style off the busy Baltimore waterfront today. Indeed, not only will this very special boat not be there, but it's a moot point as to whether she still exists. Put another way: Does enough of Saoirse still exists to allow a re-creation of this wonderful little ship to be properly classified as a re-build?

The voyage of the Saoirse in 1923-1925 only gains further lustre and wonder with the passage of time. It was an achievement of greatness, yet of beautiful simplicity. It was a uniquely pioneering venture made by an Irish skipper in an Irish designed-and-built vessel, and it was the first major voyage by an Irish ship of any size flying the Tricolour ensign of the new-born nation.

Saoirse under her original ketch rig in the 1950s, but with a boom fitted to the mainsail. Conor O'Brien had a loose-footed mainsail, and as evidenced here, the sail would have set much better but would have needed more attention in handling. (From a photo by Eric Hiscock)

In dry dock during the 1950s, Saoirse's "cod's head & mackerel tail" hull shape is clearly seen. Yet in the Great Southern Ocean on her voyage round the world south of the Great Capes, this bluff little 42ft ketch regularly logged 180 miles a day in comfort.

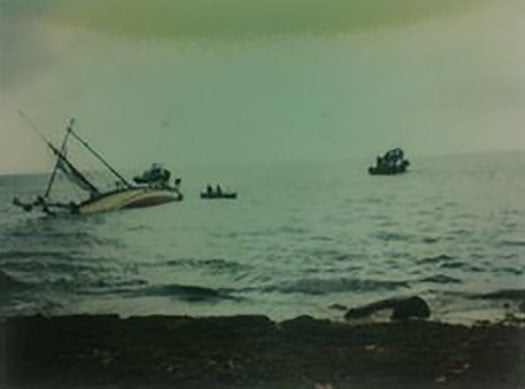

The wreck of the Saoirse in Jamaica, 1979.

Thus when the news in 1979 of Saoirse's destruction in a hurricane in Jamaica was confirmed, if anything it added to the legend. But it also meant that the only other boat created by the same team in the same place – the 56ft trading ketch Ilen (1926) – acquired added significance. But she was a long way away, still working the stormy seas around the Falkland Island, for which she'd been built after the islanders had been so impressed by the capabilities of the Saoirse, when she called there after rounding Cape Horn from the west, that they ordered a bigger sister-ship to become the inter-island workboat .

Yet thanks to a totally single-minded approach by Gary MacMahon of Limerick, Ilen was brought back to Ireland in 1998. And though it has taken quite a while for the various ideas to become reality, she is now well on the way to what has become a very public restoration with Liam Hegarty at Oldcourt Boatyard near Baltimore, while the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick has become part of the fabric of Shannonside life, building not only the deckhouses and spars for Ilen herself, but an interesting selection of smaller boats ranging from traditional Shannon gandelows to the new CityOne sailing dinghies.

A man who just doesn't give up. Gary MacMahon of the Ilen School in Limerick. Photo: W M Nixon

By any standards, all these projects would be remarkable achievements in themselves. But in addition to his day job running one of Limerick's leading design studios, Gary MacMahon has for twenty years and more been quietly accumulating every bit of documentation of all sorts there is to be found relating to Saoirse.

It's an absolute treasure hoard of old photographs, certificates, plans, artefacts and other materials. And through this collecting, he has become well acquainted with Anthony Bolton who was Saoirse's last owner. Bolton had the misfortune of seeing his beloved boat destroyed by a hurricane in Jamaica before rescue attempts could save her after she'd dragged her anchor and gone ashore.

But though Saoirse was broken up by the battering of the hurricane, substantial pieces of her remained on the sea bed, and two sea-worn iron hanging knees – lovingly fitted by the Baltimore shipwrights 93 years ago – have recently been confirmed as definite relics of the wonderful little ship.

The hull lines of Saoirse as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927 before the start of that year's Fastnet Race (from which she retired, as endless windward work was not what she was designed for). Thanks to documentation of this quality, it will be possible to re-build Saoirse with precision. But in fact it has emerged that, such was the skill of Tom Moynihan and his boatbuilders in Baltimore in 1922-23, Saoirse as built very accurately followed the original lines drawn by O'Brien and Moynihan.

Saoirse's hull sections as recorded by Uffa Fox in 1927.

More importantly, though, the word is that much of the keel may still be intact. So just as he somehow got himself to the Falkland Islands to buy Ilen back in 1997, Gary MacMahon will shortly be going on the much easier journey to Jamaica for some real on-the-spot research as to just how much of Saoirse survives.

These days, it need only be a very small piece of the original to count as a re-build. But the spirit of the Ilen School is such that even if they find nothing at all in Jamaica, the notion of re-creating Saoirse is gaining so much traction, with that great shipwright Liam Hegarty among those totally taken with the idea of seeing Conor O'Brien's characterful little masterpiece sail again, that already the idea has acquired its own momentum.

But there'll be time enough when winter comes around again to give proper attention to the full range of Saoirse material which Gary MacMahon has amassed in order to ensure an authentic re-build. Meanwhile, this weekend may be seeing the new classic and traditional boat season kick into action in Baltimore, but already things are well under way in France, with last week's huge gathering in the Morbihan on the Biscay Coast, to which seven Dublin Bay Waterwags travelled, and eight returned.

The wonders of the Morbihan. A very small part of the fleet at the Sailing Week eight days ago, with four of the Dublin Bay Water Wags at mid left. Photo: Courtesy Judith Malcolm

Like all the great French classic and tradboat festivals, the Morbihan event (it's full title is La Semaine de la Voile du Golfe de Morbihan, that's Morbihan Sailing Week in simple English) was mind-bending in terms of numbers, with 1200 boats of all shapes and sizes taking part. But the scale and layout of the Morbihan is such that it could well cope. The extensive inlet has six main ports, so the fleet was divided into six sub-groups of around 200 boats each. Everyone mingled out on the water during the day, then each night of the week-long festival saw your group going to a new port.

Two little Water Wags a long way from home – Ian & Judith Malcolm in the hundred year old Barbara (left) and Guy and Jackie Kilroy in Swift (right) in the midst of "sundry boats" in the Morbihan eight days ago. Photo courtesy Judith Malcolm

It worked, and it worked so well that the Irish flotilla of one Shannon One Design (Reggie Goodbody) and seven Water Wags not only had themselves a fine old time, but in a reversal of the usual story where our people return from distant places short of a boat or two, they came back with eight Wags, as Adam Winkelmann was united with his new boat. It was built in France as a boat-building academy exercise with a finish so exquisite that it was on exhibition in a marquee, but he was allowed to bring it home with him to Dublin Bay.

Far to the southwest in Baltimore, today we'll see a complex programme, as several traditional rowing craft (including a 23ft traditional Shannon cot or brochaun, the latest creation of Limerick's Ilen School built by a team headed by Tony Daly) were due to launch last night to berth at the pontoon in Skibbereen beside the West Cork Hotel. Today at 11am they start a rowing race all the way down the Ilen to Baltimore. Fortunately, the tide is ebbing.....

The new 23ft Shannon cot or brochaun is the latest creation of the Ilen School in Limerick. The cot's usual task was to head upriver from Limerick to fish, but today this boat will be rowed down the River Ilen from Sibbereen to the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival.

The rest of the day will see sailing and rowing races off Baltimore with a prize-giving dinner tonight in Baltimore Sailing Club presided over by Tom MacSweeney of this parish, then tomorrow (Sunday), as the one day Seafood Festival gets into full swing, there's perhaps the most interesting event of all afloat. This is the Pilot Race, in which the sailing boats put out to sea, and then turn and approach the harbour to be met by racing gigs each of which has to put a pilot on board one of the sailing craft which then race back into the harbour – it all makes for mighty sport.

Bowsprits at the ready, and the island ferry coming into port – it can only be Baltimore at Woodenboat Festival time

If you can identify even half of the boat types here, then you should be in Baltimore this weekend.

If your heart is with classic and traditional sailing boats, you can get an abundance of them by being in Baltimore this weekend, and then by being along Dublin's Liffey for the Riverfest in a week's time for the Bank Holiday weekend. It's a three day event (May 30th to June 1st) based on Poolbeg Y & BC, with the Old Gaffer's Leinster Trophy Race in Dublin Bay on Saturday, and then two days above the bridge for all sorts of city festivities and boat parades through to Monday evening.

The 117-year-old Howth 17s will be returning to the Dublin Riverfest in a week's time. Photo: W M Nixon

The famous waterborne ballet of the Dublin Port tugs Shackleton and Beaufort will be a main event in the Dublin Riverfest over the Bank Holiday Weekend of May 31st-June1st. Photo: W M Nixon

Following that, on Saturday 6th June out in Howth, the Classic Lambay Race is being provided within the annual Round Lambay Regatta (it dates back to 1904), with the Old Gaffers and Traditional boats joining the 117-year-old Howth Seventeens for a direct circuit from a pier start out to Lambay, round it and back again direct, with no fancy special mark rounding in between.

Defending champion in the Classic Lambay is OGA International President Sean Walsh of Dun Laoghaire with his cutter Tir na nOg, and extra interest is added this year as the fleet will include Dickie Gomes' 1912-vintage 36ft yawl Ainmara, built in Ringsend but now a longtime resident of Strangford Lough. There's a certain edge to Ainmara's involvement, as she was overall winner of the cruiser division in the 1921 Lambay Race when still owned and sailed by her designer-builder John B Kearney. But if you think this remarkable historic link will cause her opponents to give her an easy time of it, you're much mistaken.

The 103-year old Ainmara – seen here on her home waters of Strangford Lough with the Mourne Mountains in the distance – will be returning to the Lambay Classic at Howth on June 6th 2015, which she last won in 1921. Photo: Pete Adams

Sean Walsh is having a busy year of it, as his duties as OGA President take him hither and yon, while Tir na nOg will be flagship for the OGA Cruise-in-Company which will follow the big one of 2015, the Glandore Classics Regatta from July 18th to 24th.

But for this weekend, he's in his home waters of Dublin Bay on a venture which means a lot to him, the OGA Youth Sailing Project at Poolbeg under the direction of Liam Begley. It's for youngsters who might not otherwise get a chance to sail. They're taken out to learn the ropes aboard two fine gaff cutters, the Clondalkin Community group's majestic Galway Bay hooker Naomh Cronan, and the OGA President's own Tir na nOg.

When we remember that many folk head from Dublin towards Cork to go sailing, it's intriguing that in this case the young people have come the other way, as they're a group from Mayfield Community School which has eternal fame through being the old school of Roy Keane.

The tyro sailors from Mayfield – there's nine of them, all in the 15-16 age group - have already become boat-acquainted through the Meitheal Mara Community Boatyard in Cork city. But the outing to Dublin puts a different spin on it all, as the first stage is devoted literally to teaching them the ropes, then after the sailing programme is completed out in the bay, the shift in skills is demonstrated by command of the two gaff cutters being given over to the Mayfield crews, who then have to sail them back to port.

OGA President Sean Walsh (top right) with Junior Gaffers from Mayfield Community School in Cork aboard Tir na nOg in Poolbeg in Dublin. Photo: John Galloway

Junior Gaffers from Cork and Senior Gaffers from Dublin aboard the Naomh Cronan Photo: John Galloway

In all, it's an entertaining balance between an outing to Dublin, a chance to learn in a fun environment, and a real opportunity to demonstrate that practical skills have been well and truly acquired. And before somebody is driven to send in a rude comment after seeing these two photos of last year's Youth Sailing Project course, I hasten to assure you that when they do go sailing, everyone wears a lifejacket.