In recent weeks, much of the attention on the traditional boat-building Mecca of Oldcourt in West Cork has been focused around the complex moves involved in vacating the 56ft ketch Ilen from the boat-building shed writes W M Nixon. This meant safely re-locating her through the very crowded boatyard to a secure commissioning berth where a sheltering tent could be erected to allow the fitting-out work to proceed whatever the weather.

Then in time, while fitting the interior has been proceeding, there followed the “blind stepping” of the two masts which had been trucked down from the Ilen Boat-Building School in Limerick, where the massive spars and rig had been built and pre-assembled.

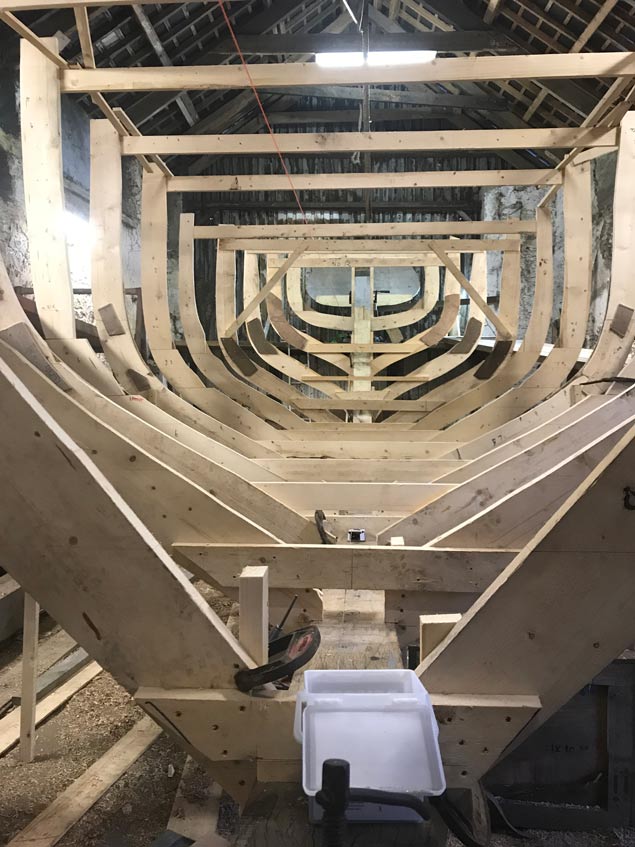

“We have a shape – we have the shape.” In boat-building terms, putting the moulds in place is just part of the process, but for the casual observer it gives a first vivid impression of what the re-built Saoirse will look like. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“We have a shape – we have the shape.” In boat-building terms, putting the moulds in place is just part of the process, but for the casual observer it gives a first vivid impression of what the re-built Saoirse will look like. Photo: Gary MacMahon

After restoring the Ilen at Oldcourt, the first stages in re-building Saoirse in the same shed provide the clearest message that a 42-footer is very much smaller than a 56-footer, yet it was the 42-footer that sailed round the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

After restoring the Ilen at Oldcourt, the first stages in re-building Saoirse in the same shed provide the clearest message that a 42-footer is very much smaller than a 56-footer, yet it was the 42-footer that sailed round the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

All this has been safely dealt with despite some periods of freakishly bad weather. But it had to be done on time, as the shed was needed because it had been agreed to start work in January on the re-build of Conor O’Brien’s 1922-built 42ft Saoirse. This project – for experienced sailor Fred Kinmonth of Hong Kong – will be in honour of Saoirse’s great achievement of 1923-25, the first global circumnavigation of the world by a cruising yacht south of the Great Capes.

So while much attention has been on the brightly-painted Ilen and the flurry of activity around her, in the shed shipwrights Liam Hegarty and Fachtna O’Sullivan and their team have been left in relative peace for the key initial stage of creating Saoirse’s backbone from various very substantial pieces of carefully-selected oak.

Saoirse’s backbone could only begin to come together thanks to a complex process for sourcing suitable oak. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s backbone could only begin to come together thanks to a complex process for sourcing suitable oak. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But as Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Project puts it: “In taking on a job like this, you have to create a new supply chain. There is no line of supply for traditional boat-building on this scale, and we had to make our own way in finding pieces of sound oak which would help to provide the myriad of shapes from which the backbone and the frames will eventually be created”.

The upshot was that if a great oak came down anywhere in Munster, they’d soon be on the spot to see if anything usable could be salvaged from it. And even then, after the processes of seasoning and so forth, that was only the beginning of the job. A piece of oak might be worked on until it was nearly ready to be installed in the backbone, but then some aspect of the almost-finished section would give out the wrong messages, and it would be discarded and an alternative piece sought from the stockpile.

Saoirse may be significantly smaller than Ilen, but renewing her backbone has involved working with substantial pieces of oak, some of which didn’t pass the final test. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse may be significantly smaller than Ilen, but renewing her backbone has involved working with substantial pieces of oak, some of which didn’t pass the final test. Photo: Gary MacMahon

So it was patient, painstaking work, it took time, and it was best done in peace and private. But finally the makings of the backbone were in place, and there then could be visible progress – the erection on the keel, from stem to stern, of the temporary moulds which would show precisely the ultimate shape of Saoirse’s frames.

This has been taking place during the past week, and though it’s essentially a mock-up, just an integral part of the building process, nevertheless it feels as though the project has taken a mighty leap forward. And as with everything to do with Saoirse, it’s redolent with history.

Saoirse’s sternpost – Tom Moynihan insisted on lengthening the counter beyond Conor O’Brien’s hyper-economical original design. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s sternpost – Tom Moynihan insisted on lengthening the counter beyond Conor O’Brien’s hyper-economical original design. Photo: Gary MacMahon

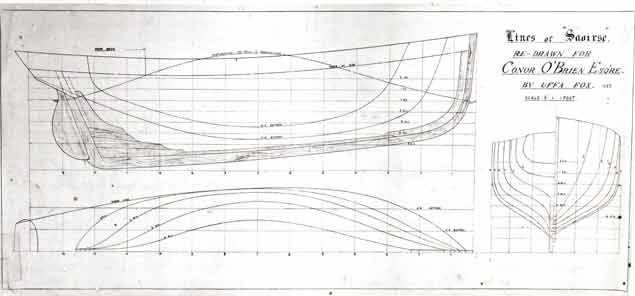

While Conor O’Brien of Foynes and Tom Moynihan of Baltimore may have sketched out Saoirse’s lines (with Moynihan insisting the inelegantly short stern be lengthened a little), their drawings were only very rudimentary. But after the great voyage, Saoirse was famous. When Conor O’Brien took her to Cowes to do the 1927 Fastnet Race, the already-legendary Cowes-based designer Uffa Fox took off the boat’s lines.

As was right and proper, the lines sketched by O’Brien and Moynihan were remarkably close to the little ship as she was finished. But it was the lines as taken off by Uffa Fox which have been used in the process whereby the moulds have been assembled and erected, and this has been a speedy process which by Friday night was providing a vision of Saoirse which has an air of reality to it.

At the end of 2017, it was still a project in planning. But now, we’re already seeing something. The dream is becoming reality.

Saoirse’s lines as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927

Saoirse’s lines as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927

Saoirse sailing in Cornish waters during the 1950s while in the ownership of the Ruck family. Photo courtesy Gary MacMahon

Saoirse sailing in Cornish waters during the 1950s while in the ownership of the Ruck family. Photo courtesy Gary MacMahon