Displaying items by tag: Yacht Design

Yacht designer Mark Mills is the latest speaker in the Royal Irish Yacht Club’s special series of online talks tonight, Wednesday 10 June.

Mark Mills started Mills Design in 1995 with an order from Peter Beamish for the 31ft Aztec, built in Malahide by Mizzen Marine.

Building on her success, his custom designs have won numerous titles including the 100ft Wallycento Tango, the Maxi72 World Champion Alegre 3, multiple IRC Championship winners Mariners Cove and Tiamat, and the 69ft IMA Mini-Maxi Champion Alegre.

Equally his production designs such as the IC 37 for the NYYC, double ORC World Champion Landmark 43, C&C30, Cape 31, King 40 and DK 46 are well known worldwide.

Originally from California, Mills studied yacht design at the Southampton Institute while racing with some of the best teams in the UK.

He won with the Seahorse Sailor of the Month in December 2014, the 2009 Irish Sailor of the Year award, was named the Asian Marine & Boating Best Designer of 2010 and 2015, and recognised closer to home with Wicklow Sailing Club’s Irish Holly trophy.

Most recently, he won first prize at the premiere edition of the MDO Montecarlo prize for the Wallycento Tango.

A member of the RORC Technical Committee and an advisor to both the US and Irish IRC owners groups, Mills has spoken around the world on yacht design and rating rules for events such as IBEX both in the US and Europe, the International Yacht Forum, and regularly at ICRA meetings.

He was one of the initial HPR Committee members who helped draft the High Performance Rule for the NYYC, and subsequently joined the Sailing Yacht Research Foundation (SYRF) Advisory Board.

This evening, he follows the likes of Julian Everitt in the RIYC’s special series of talks with some of the world most renowned yacht designers. RIYC members should contact [email protected] to attend this talk, which starts at 7.30pm this evening, Wednesday 10 June, via the Zoom platform.

Yacht Designer Julian Everitt Is Latest Speaker In RIYC’s Members-Only Online Talks Series

The Royal Irish Yacht Club welcomes acclaimed yacht designer Julian Everitt as the latest speaker in its members-only series of online talks tomorrow evening, Wednesday 27 May.

First inspired to become a yacht designer when he saw Sceptre leaving Poole Harbour in 1958 in training for the America’s Cup, Julian Everitt produced his first full design with an RORC Rule half-tonner in 1968.

His first IOR design, for Bantam Yachts, provided the basis for a string of successful half-tonnes, then quarter-, three-quarter- and one-tonners.

Then came the E-Boat, designed in 1974 to the IOR, of which over 250 were built; the Mirador, a 20ft lifting keel yacht in collaboration with the Daily Mirror newspaper; and the radical Wavetrain, which currently sails out of Greystones.

Julian also edited Seahorse Magazine between 1970 and 1975, and has contributed to many sailing magazines and journals over the years — so expect strong views, such as his position on how ratings systems shape yacht design, and not always for the best.

Julian Everitt’s talk is part of the mini-series on yacht design that kicked off two weeks ago with Ron Holland. Only RIYC members can attend via the Zoom platform from 7.30pm on Wednesday 27 May. Contact [email protected] for details on how to attend.

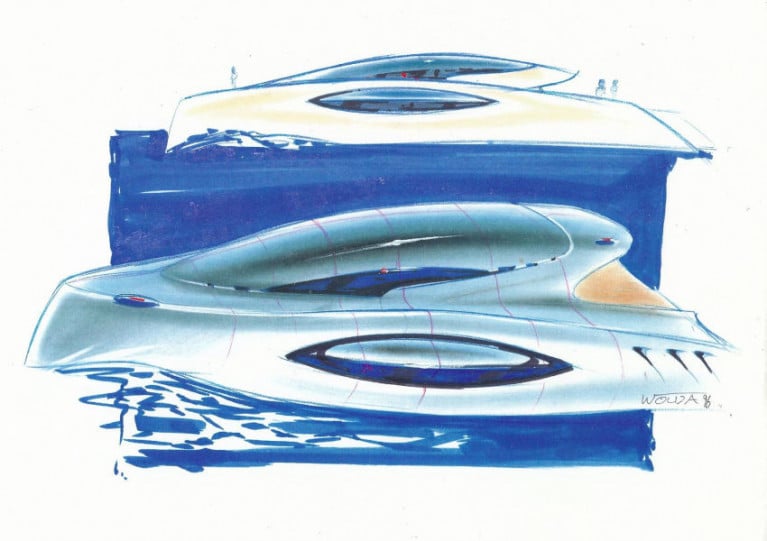

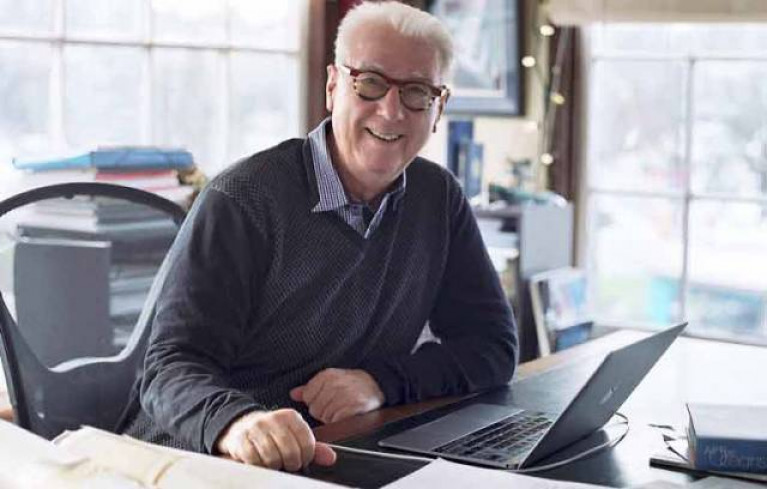

This week’s slot in the Royal Irish Yacht Club’s ‘Home Together’ series of online talks sees yacht designer Ron Holland headline a new mini-series featuring some of the best known names in international yacht design.

Julian Everitt, Mark Mills and John Corby are some of the other legendary figures who will give their own virtual talks over the coming weeks, following Holland’s introductory talk tomorrow evening (Wednesday 13 May)

And what’s more, Holland will be joined on this panel by Ireland’s own veteran sailing superstar Harold Cudmore.

For over 50 years, Ron Holland’s innovative designs have repeatedly shaken up the world of sailing.

Renowned as one of the most successful and sought-after designers in the highly competitive world of international ocean racing, he later brought his influence to — and continues his success in — the superyacht industry.

Holland’s online talk is set for 6.30pm on Wednesday 13 May. Contact [email protected] to register to attend.

Take a Bow! How Should Yachts Really Begin & End?

The accepted and popular shapes of boats and yachts in different ages changes so much that you’d be forgiven for thinking that their functions also change completely to suit the requirements of each new era. Of course, design development, measurement rule changes, and new ways of construction are major contributing factors in re-configured appearance from one period to the next. But beyond that, there’s the matter of taste and what people have become accustomed to - the Beauty of one age can be the Beast of the next.

Take a bow today….the new-style stem on the MGM Boats-imported Sun Fast 3300 Cinnamon Girl as seen last month in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Take a bow today….the new-style stem on the MGM Boats-imported Sun Fast 3300 Cinnamon Girl as seen last month in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

8 Metre Class

Eddie English of Cobh sent us wandering along a picturesque section of memory lane the other day when he came up with a collection of photos by Pascal Roche showing the quartet of International 8 Metres which were very much the style-setters on Cork Harbour in the 1950s and 1960s, and a quickfire exchange of thoughts about them and the people in them was just the job for some diversion from the inevitable contemplation of the ill-effects of The Enemy of the People, aka Covid-19.

For by classic standards, every one of those Cork “straight Eights” was a beauty, dating as they did from the vintage years of the class in the 1930s. We hasten to say they weren’t eight metres long - they were designed to a formula in which, once the maths were completed, the answer was eight metres, and the result was boats of long and stylish overhangs which were in the 47ft to 50ft overall length range.

All four Cork Harbour International 8 Metres were built in different countries – this is the longest of them, Perry Goodbody’s 50ft Christina of Cascais, designed by Tore Holm and built in Sweden in 1936. Photo: Pascal Roche

All four Cork Harbour International 8 Metres were built in different countries – this is the longest of them, Perry Goodbody’s 50ft Christina of Cascais, designed by Tore Holm and built in Sweden in 1936. Photo: Pascal Roche

As it happened, the Cork group encompassed both extremes, with Sam Thompson’s Wye being a slip of a thing with minimal headroom, while Tom Crosbie’s If was one of the heftiest International Eights ever built, and even managed standing headroom. Needless to say, Wye was a flyer in lighter winds, but was remarkably wet offshore, as I discovered when delivering her from Cork with new owners to the Clyde at Easter 1968, when the wind remained very determinedly brisk and cold out of the east.

The little one…..Sam Thompson’s Wye was designed by Charles E Nicholson and built by Camper & Nicholson in 1935. Her first owner requested that she be as much as possible like a miniature of Thomas Sopwith’s almost-successful Nicholson-designed America’s Cup Challenger Endeavour of 1934.

The little one…..Sam Thompson’s Wye was designed by Charles E Nicholson and built by Camper & Nicholson in 1935. Her first owner requested that she be as much as possible like a miniature of Thomas Sopwith’s almost-successful Nicholson-designed America’s Cup Challenger Endeavour of 1934.

By contrast, If could give a good account of herself offshore and in a breeze racing out of Crosshaven. She was thus a regular star in the West Cork Regattas when they were still known as the West Cork Regattas and people didn’t feel the need to call them Calves Week. But it was Denis Doyle with Severn II who was the most determined RORC campaigner. This resulted in a memorable (or perhaps better forgotten) experience in the RORC’s Beaumaris to Cork Race, which started in the Menai Straits in North Wales.

As the Coningbeg Lightvessel off the Saltee Islands was a mark of the course, there was a tradition on Irish cruising and offshore racing boats of carrying up-to-date newspapers which could then be chucked aboard the manned lightship as they went past. With Severn II in the lead, her distinguished visiting helmsman (who had better remain anonymous) was so determined to complete this manoeuvre in close style that he failed completely to notice that the lightship’s boom, to which service boats would be secured, was slightly extended. The result that while Severn did indeed sweep beautifully alongside and neatly deposit the newspapers, there was a crash from aloft, and there was her mast – gone.

The great Denis, who’d been off watch, took it all in his usual phlegmatic style, and they cleared the wreckage away and set off under the little auxiliary engine for the slow haul to the nearest port at Dunmore East, for in those days Kilmore Quay was a very primitive place with no berthing of any kind for yachts. Denis then retired below again to resume his sleep, but was awakened some time later by suspicious-sounding noise and kerfuffle in the cockpit.

Denis Doyle’s Severn II off the original Royal Cork YC clubhouse at Cobh. Designed by Alfred Mylne and built in Scotland in 1934, Severn II was the second international metre-style boat Denis Doyle raced offshore, as he started his RORC career with the Thirty Square Metre Vanja IV. Photo: Pascal Roche

Denis Doyle’s Severn II off the original Royal Cork YC clubhouse at Cobh. Designed by Alfred Mylne and built in Scotland in 1934, Severn II was the second international metre-style boat Denis Doyle raced offshore, as he started his RORC career with the Thirty Square Metre Vanja IV. Photo: Pascal Roche

He erupted on deck (in his pyjamas, mark you) to find that the mast-breaking helmsman had observed that a ship was about to pass nearby, and as they’d no means of signalling, he was trying to set off a flare in order to get a tow, as he was convinced the little engine would never get them to port.

That did it for Denis. “My God,” says he, “You break my mast. And now you’re trying to set my boat on fire. We’ll get to Dunmore East or somewhere else under our own power. And that’s the end of it”.

With boats so beautiful in the classic style, while the 8 Metre class have long gone from Crosshaven, they’ve been revived in restored or even new-build form all over the world. But as they’re specialist craft totally at variance with the modern boats of extremely short ends and straight or even reverse stems, the contemporary world of the long and elegant International 8 Metre Class is a very private place in which the strongest fragrance is the reassuring aroma of wealth.

As for the design preferences which set the shape of the Cork-based 8 Metres, it is also seen in another 1930s creation, the Dublin Bay 24s, which lasted more than fifty years and have since seen restorations at various stages, the most complete being Periwinkle based in Dun Laoghaire.

Classic good looks. Dublin Bay 24s racing in their Golden Jubilee regatta in 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

Classic good looks. Dublin Bay 24s racing in their Golden Jubilee regatta in 1997. Photo: W M Nixon The restored Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle. In addition to providing more than fifty years of great racing in Dublin Bay, the boats were cruised extensively, and in 1963 one of them won the RORC Irish Sea Race

The restored Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle. In addition to providing more than fifty years of great racing in Dublin Bay, the boats were cruised extensively, and in 1963 one of them won the RORC Irish Sea Race

Meanwhile, in mainstream sailing, we’ve now entered an era in which even Superyachts seem determined to mimic the trend in the most advanced offshore racers in having vertical or even reverse stems. You can understand the dictates of fashion (however odd) pushing their way through even into superyacht design, so all power to Ron Holland, who has tried to design his superyachts so that they look elegant in the classic style, with matching overhangs fore and aft.

Ron Holland’s personal dreamship, the 73ft Golden Opus, shows his preference for classical elegance

Ron Holland’s personal dreamship, the 73ft Golden Opus, shows his preference for classical elegance

This is something of which seasoned professional crews heartily approve, for as one of them said with some vehemence: “If you’re trying to get some work done right on the stemhead in a rough seaway in a superyacht with a vertical stem, you’ll find you’re being power-hosed all the time, and can regularly expect to be washed like a rag doll – sometimes with painful consequences - back along the deck. But when you’re right forward in one of Ron’s boats, the seas are sweeping across the deck safely astern of you, and all’s well with the world”.

Superyacht Sea Eagle II

Despite that, there are already superyachts sailing with reverse stems, which may ultimately mean that they’ll have to devise ways of doing any necessary work at the stemhead from a special compartment inside the hull. But that is not a problem most of us will ever have to deal with, although it will be a thought for an Irish professional sailor who is on the commissioning crew of the latest mega-blast on the Superyacht scene, the 81 metre aluminium-hulled Dykstra-designed Sea Eagle II (that’s 266ft in old money) which emerged with inches to spare from the enormous Royal Huisman construction sheds in The Netherlands on January 8th, the largest yacht ever built by the company.

The big one. The new 81m Sea Eagle II emerges with inches to spare from the Royal Huisman sheds in The Netherlands with inches to spare on January 8th. At 266ft and built in aluminium, she is the largest vessel ever completed by the firm.

The big one. The new 81m Sea Eagle II emerges with inches to spare from the Royal Huisman sheds in The Netherlands with inches to spare on January 8th. At 266ft and built in aluminium, she is the largest vessel ever completed by the firm.

Owing to the pandemic lockdown, work is currently on hold in the completion process. But with a vessel this size (properly speaking, she’s a ship) they’ve a shore-based caretaker crew of six including our Irish sailor, of whom four are always on board while the others are in dedicated accommodation ashore. There, all enjoy the services of the crew chef, so the biggest problem may well be keeping the personal weight down.

More of a ship than a yacht, Sea Eagle II is privately owned but may be available for charter.

More of a ship than a yacht, Sea Eagle II is privately owned but may be available for charter. Although she has substantial twin engines, Sea Eagle II is designed as a serious sailing proposition

Although she has substantial twin engines, Sea Eagle II is designed as a serious sailing proposition

Keeping weight down in the ends of his yacht has always been one of the priorities of Gerry Dykstra, who founded the design company in 1969. Thus although his own much-voyaged 53ft Bestevaer 2 is completely straight-stemmed with a short stern to match, within the accommodation there is virtually nothing in the forward and aft sections.

Gerry Dykstra’s 53ft Bestevaer 2 in Svalbard. All accommodation and weight is concentrated as much as possible towards the centre of the boat

Gerry Dykstra’s 53ft Bestevaer 2 in Svalbard. All accommodation and weight is concentrated as much as possible towards the centre of the boat

Innovative designer Gerry Dykstra – his personal heroes are G L Watson and Nat Herreshoff

Innovative designer Gerry Dykstra – his personal heroes are G L Watson and Nat Herreshoff

Intriguingly, however, Dykstra says that his own yacht design heroes are Scotland’s G L Watson and America’s Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, who were in the vanguard in the introduction of bows with long overhangs in the 1890s. But in order to grasp that and how it came about, maybe we should take a quick canter through stem development in the 1800s.

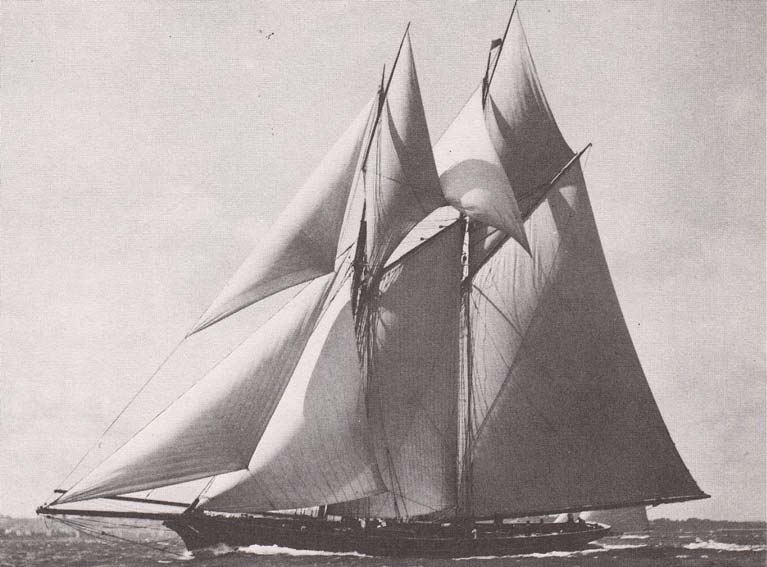

Fishing boats always tended to have short overhangs forward, for several reasons, not least of them being the fact that their crowded harbours meant that with bowsprits raised, they could pack more boats in. Many yachtsmen felt that the straight stem type was also best for their needs, but the great sail trading ships and naval vessels gradually developed bowsprits which set so many multiple headsails that they became spars within their own right, and were best supported by the development of the clipper bow. It looked just right as it combined elegance with functionality, and by the time the schooner America arrived across the Atlantic in 1851, clipper bows seemed as popular as straighter stems.

This became even more the case in the 1860s, the great era of the racing schooners, which is when Ireland comes in on the story in a significant way, as the most successful schooner was linen magnate John Mulholland of Belfast’s “wonderful Egeria” of 1865, winner of many trophies during a long career.

The triumph of the clipper bow – John Mulholland’s schooner Egeria was the top performer in the 1860s and ’70s.

The triumph of the clipper bow – John Mulholland’s schooner Egeria was the top performer in the 1860s and ’70s.

Yet in time, design developments and new rating rules saw a revival of cutters, and straight-stemmed ones at that, and this time the Irish input was by whiskey king John Jameson of Dublin, whose Irex of 1884 (designed by Alexander Richardson of Liverpool) was in the trophy lists for the rest of the 1880s.

Everyone thinks that it was uber-grocer Thomas Lipton of Monaghan and Glasgow who first demonstrated the commercial benefits of high profile yachting campaigns with his publicity-laden America’s Cup challenges. But it was the notoriously shy John Jameson who was ahead of the curve in this area, for every time Irex won a trophy, as she did the classic regatta circuit right through the season at many venues, the name John Jameson would appear in the sports pages, and up and up went the sales of his Irish whiskey.

Back to the straight stem – John Jameson’s Irex was the most successful cutter racing in the 1880s

Back to the straight stem – John Jameson’s Irex was the most successful cutter racing in the 1880s

But while John Jameson was shy, his brother Willie was an exuberant extrovert who was recognized as one of the best amateur sailors of his generation, and through his association with the success of Irex he became part of the Prince of Wales’s sailing set. So much so, in fact, that when the Prince ordered the construction of the new royal racing yacht Britannia in the late Autumn of 1892 to designs to G L Watson, it was Willie Jameson who was appointed Owner’s Representative for the project.

But there was even more of an Irish element to it than that, as Britannia was generously commissioned in order to provide a training partner for Valkyrie II, the Watson-designed America’s Cup challenger ordered a few weeks earlier from Watson by Lord Dunraven of Adare, Co Limerick.

All of that’s as may be, but in terms of our story about the development of bow shapes, the fact is that both Valkyrie II and Britannia had the new-look long overhang bows, and though in time Britannia came to be thought of as the perfect ideal of what a classically good-looking yacht should look like, when she and her near sister Valkyrie II appeared in the Spring of 1893, they were many who didn’t like the looks of the stems at all, and described them somewhat disparagingly as “spoon bows”.

The new G L Watson-designed Britannia developing power and speed in 1893, when her innovative stem was disparaged as “a spoon bow”. For her first four very successful seasons, the Royal Sailing Master was Willie Jameson of Portmarnock, and in time her hull shape became accepted as classically elegant.

The new G L Watson-designed Britannia developing power and speed in 1893, when her innovative stem was disparaged as “a spoon bow”. For her first four very successful seasons, the Royal Sailing Master was Willie Jameson of Portmarnock, and in time her hull shape became accepted as classically elegant.

Yet today Gerry Dykstra of the vertical stems is enthusiastic in his admiration of the work of G L Watson (who of course introduced many other performance-enhancing design concepts) and he’s equally admiring of Nat Herreshoff, whose successful America’s Cup defenders if anything went even further in extending the bow overhang.

The idea underlying it all was that when the yacht was sailing, the long overhangs effectively lengthened the working waterline length thereby increasing the boat’s speed potential, and in practice, this was so evidently true that within three decades the RORC Rule for providing a handicap rating for the newly-developing sport of offshore racing was punitive in its treatment of long overhangs.

Myth of Malham

So much so, in fact, that some very odd boats soon began to appear, with their ultimate expression coming in 1947 with John Illingworth’s 40ft Myth of Malham, which won everything on this side of the Atlantic, but didn’t do so well in America, where they reckoned that they should have rating rules which encouraged the success of yachts that reflected the priorities of classic nautical design beauty.

John Illingworth’s Myth of Malham, built in 1947 to designs by Laurent Giles with very considerable input by the owner. As the RORC rating rule penalized long and elegant overhangs, Myth was built (by Hugh McLean in Scotland) just about as short-ended as possible.

John Illingworth’s Myth of Malham, built in 1947 to designs by Laurent Giles with very considerable input by the owner. As the RORC rating rule penalized long and elegant overhangs, Myth was built (by Hugh McLean in Scotland) just about as short-ended as possible. The successful Sparkman & Stephens-designed 73ft Bolero of 1949 vintage. The American offshore rule made no secret of the fact that they wanted to encourage good-looking boats of classic elegance

The successful Sparkman & Stephens-designed 73ft Bolero of 1949 vintage. The American offshore rule made no secret of the fact that they wanted to encourage good-looking boats of classic elegance

Such yachts still appear, but they’re always designated as “Spirit of the Classics”, for in yacht design generally, things are moving so fast that straight stem on a new-build has long ceased to be a matter of comment, and the aspiration now is to create a bow shape which can somehow furrow the briny deep without leaving any foaming furrow marks at all. Strange times indeed. Stay safe.

Wicklow Yachtsman Mark Mills Wins 'Asian Marine Designer of the Year Award' at Shanghai Boat Show

#yachtdesign – Mark Mills has been honoured with the Best Yacht Designer award at this year's Asian Marine & Boating Awards. It is the second second time the Irish Cruiser Racing Association (ICRA) Committee member has lifted the award. The ceremony was held on the opening day of this year's Shanghai Boat Show as part of the Land Rover Gala Dinner held at the Hyatt on the Bund Hotel, Shanghai marking the 20th Anniversary of the Shanghai Boat Show.

Mills is currently working on a number of projects including his C&C 30 design that will debut here at Volvo Dun Laoghaire regatta in July. The Wicklow based designer has also launched 'SuperNikka' for Roberto Lacorte at a celebration last week, attended by hundreds in the beautiful new port of Marina Di Pisa in Italy. This 'aggressive' 62' Cruiser/Racer was developed with a team including Vismara Marine, North Sails Italy, and Lacorte. A second build is underway.