For most participants, sailing is a team effort – we sail as part of a crew in a reasonably sociable mutually-supportive environment. Yet increasingly the best-known sailors are those who compete solo. While we’re naturally interested in the great sailing commanders leading formidable teams which will include many specialists such as rock-star navigators and tacticians, our human feelings are more readily drawn to the lone sailor, whose ultimate success or failure has just one very human focal point. W M Nixon reflects on the current crop of Irish sailors noted for going it alone.

Ireland’s Tom Dolan heads off towards St Barth in the Caribbean tomorrow from Concarneau in Brittany with his shipmate Tanguy Bouroullec, racing in their Figaro Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance westward across the ocean in the Transat AG2R La Mondiale. Yet although it’s a two-handed race, we are mostly aware of the crew of Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance as significant solo sailors in their own right, with Bouroullec fourth and Dolan sixth in a fleet of 54 boats in last year’s single-handed Minitransat.

"It is Dolan’s achievement which most captures our imagination"

And it is Dolan’s achievement which most captures our imagination, with his dogged determination and what he has attained from a standing start. For although he was one of the most promising young sailors to emerge from the Glenans training system in Ireland, when he decided to commit to a professional and mainly solo sailing career in France back in 2011, he was so very much alone. A boyhood on a family farm in north Meath provides very little training towards making your way in a strange culture in an intensely nautical place where all communication is in French.

Life’s different with a shipmate – Tanguy Bouroullec on the rail and Tom Dolan on the helm as they put in some training for tomorrow’s two-handed Figaro Transatlantic race to St Barth from Concarneau

Life’s different with a shipmate – Tanguy Bouroullec on the rail and Tom Dolan on the helm as they put in some training for tomorrow’s two-handed Figaro Transatlantic race to St Barth from Concarneau

The Figaro two-handers racing off Concarneau last Sunday – Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance is third from right.

The Figaro two-handers racing off Concarneau last Sunday – Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance is third from right.

But he stuck at it, he’s now part of the system, and though he is known as l’Irlandais Volant (“the Flying Irishman”), he is verging on having French as his first language, albeit with a very Irish twist to it now and again.

So both he and Bouroullec will be appreciate the presence of a supportive shipmate with shared goals, for both have known the loneliness of the long distance sailor. And it is something which they have had to come through absolutely on their own, for ultimately that is what it is all about - no matter how big or small the shore support team is, and no matter how often your communications are with them, in the end the pressure is on you.

In this increasing emphasis on individual achievement in sailing, it isn’t just the deep sea stuff which sees this pressure being applied. In a country like Ireland in which many people are only aware of sailing when it is high-lighted as an Olympic sport, the way that the national spotlight can focus with unnatural intensity on young solo sailors in the Olympic classes should be a matter of concern.

The national euphoria when Annalise Murphy won her Silver Medal at the Rio Olympics in August 2016 was in some ways scary to behold. Were we really doing so badly in other Olympic sports that winning just one sailing medal was a matter of near hysteria across the land? And beyond that, what sort of pressure might now be put on Annalise and her successors for subsequent Olympics?

“Announced with the headline: It’s over to you, Aoife.”

Well, we got an idea of it right here on Afloat.ie, when Annalise’s decision not to compete in the Olympic classes selection regatta in Denmark in August, in order to concentrate on completing her involvement with the Volvo World Race, was announced with the headline: “It’s over to you, Aoife.”

When life was more carefree – Aoife Hopkins revelling in big waves when she won the Women’s Laser Radials U21 Euros in France last July

When life was more carefree – Aoife Hopkins revelling in big waves when she won the Women’s Laser Radials U21 Euros in France last July

Young Women’s Radial Sailor Aoife Hopkins was immediately brought centre stage in the quest for an Olympic place, and all this at a time when her training programme had been knocked astray by a three week bout of tonsillitis. It was a reminder, were it needed, of just how much an Olympic campaign at any stage is so dependent on everything being precisely as it should be, and being in good health is just one of the key factors.

In Ireland, it’s something of which we’re acutely aware. Back in September 1972, our Olympic Dragon team of Robin Hennessy, Harry Byrne and Owen Delaney racing at Kiel were on top form, the Dragon Gold Cup already won and an Olympic medal highly likely. But then Owen Delaney was struck down by a severe flu-like virus with the entire finely-tuned structure of the Dragon Olympic campaign being knocked off balance, and any medal chances disappeared.

In recent months this year, Finn Olympic hopeful Fionn Lyden of Baltimore was taken ill with two successive viruses which knocked his plans astray, and made him realize how vulnerable a solo international sailor can be. His recovery was literally aided by team support – he was persuaded while still convalescent to sail as a member of the UCC Team in the Inter-varsities Team Racing at Kilrush, and found himself enjoying the experience so much (it helped that UCC won) that the following weekend he was captaining the UCC team in the Student Worlds Selection trials in the J/80s at Howth, and won again with his health restored.

Reflecting on this welcome turn of events, he said that the crowded and cheerful Kilrush event in particular made him realise how much of a goldfish bowl environment the top level solo sailing scene can become, and it had simply put the fun back into sailing to be part of a team again - he was getting his mojo back.

They’re a tough boat to sail – Fionn Lyden in the Olympic Finn

They’re a tough boat to sail – Fionn Lyden in the Olympic Finn

This theme of simple enjoyment from sailing is something which inevitably crops up in the more stressful solo sailing situations. We’ve long since passed the stage where, if your lone venture of whatever sort does not go through some very difficult and unpleasant challenges, then public interest wanes. The outside world needs to know that the “no pain, no gain” element is still a primary factor in their emotional attachment to the lone challenger.

But sports psychologists are in no doubt that if your longtime sense of enjoyment, of delight in sailing, does not continue to manifest itself from time to time - and preferably frequently - then trouble looms.

"The outside world needs to know that the “no pain, no gain” element is still a primary factor"

Currently, one of the best advertisements for the longterm enjoyment of sailing by a solo sailor is to be found with Ireland’s Sailor of the Year, Conor Fogerty. Anyone who followed his victory in the OSTAR last year will be well aware that he went through some horrendous experiences aboard his Sunfast 36000 Bam! But equally you got a sense of joy in sailing when the going was good, and it was all done with real style.

For the first half of this season, Conor is on a new tack. Bam! is currently being shipped back from the Caribbean after her class victory in the Caribbean 600 in late February, but for home use in Howth late last season he acquired a little classic, the Ron Holland-designed 30ft Silver Shamrock which won the Half Ton Worlds for Harold Cudmore at Trieste in 1976.

There are those who would argue that such a historic 42-year-old boat is almost worthy of consideration for display in a maritime museum. But such notions are the last thing on Conor Fogerty’s mind. On the contrary, he sees her as a charming little boat which is a delight to race against more modern boats, maybe surprising them a little now and again. Last weekend in the Dublin Bay ISORA Warm-up Race, Silver Shamrock finished third overall and first in class, while this weekend with the official ISORA Programme under way, the results will acquire a certain edge.

Conor Fogerty’s Silver Shamrock newly arrived in Howth. Under Harry Cudmore’s command, she was Half Ton World Champion at Trieste in 1976, and 42 years later, she can still give a good showing of herself. Photo: W M Nixon

Conor Fogerty’s Silver Shamrock newly arrived in Howth. Under Harry Cudmore’s command, she was Half Ton World Champion at Trieste in 1976, and 42 years later, she can still give a good showing of herself. Photo: W M Nixon

But through it all, Conor Fogerty will be having a fine old time. That’s the abiding impression you get from talking with those who sail with him in fully-crewed races. He’s an inspirational skipper who is having the time of his life leading a crew of friends, yet he is the same man who can re-set his mental attitude to put in a world class solo racing performance.

This tells us something of the level of will-power needed to continue in the solo sailing game. For although at the top level the famous skippers are supported by a complete and well-funded organisation, there are so many aspirants challenging with what is in effect a shoestring operation in every form of solo sailing that support can get spread very thin indeed, and there are inevitably events in which the imbalance of the challenge against the resources to take it on becomes the main story, rather than just the background to who might win the race. And this is arguably the case with the Golden Globe 2018.

"He is the same man who can re-set his mental attitude to put in a world class solo racing performance"

Inevitably, many in sailing have mixed feelings about this summer’s 50th Anniversary re-enactment of the Golden Globe non-stop solo Round the World challenge of 1968. It wasn’t really a race in the first place - the trophy put up by the Sunday Times was for the first boat to return to north of latitude 40 degrees N having sailed un-aided round the planet south of the great Capes from that same point. And an extraordinary selection of boats had started as soon as they were ready to go.

With the limited communications of the time, the skippers didn’t know where their rivals were, and for a long period the leader was expected to be France’s Bernard Moitessier with his steel 39ft ketch Joshua. However, he went into an increasingly philosophical frame of mind as the event progressed, and having passed Cape Horn, instead of turning left into the Atlantic to head north for the finish, he continued on past the Cape of Good Hope and Australia for the second time until he could take a left turn to the islands of the Pacific, where he retreated for a period of reclusive contemplation.

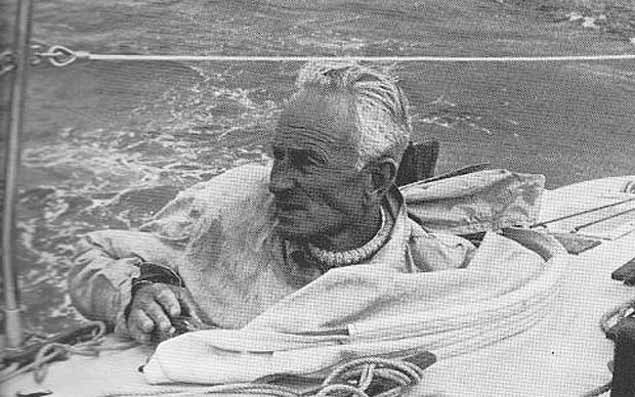

Bernard Moitessier of France with the 39ft steel ketch Joshua was expected to lead the Golden Globe in 1968, but he retired to the Pacific islands for a period of reclusive contemplation

Bernard Moitessier of France with the 39ft steel ketch Joshua was expected to lead the Golden Globe in 1968, but he retired to the Pacific islands for a period of reclusive contemplation

Meanwhile, Robin Knox-Johnston with the much smaller ketch Suhaili was battling gamely on, and in time he was first to finish with a rapturous welcome at Falmouth. He was very deservedly feted. And if sailing gave much to Robin Knox-Johnston in 1968, in the fifty years since he has re-paid it a thousandfold – his generous and imaginative contribution to our sport is beyond calculation.

"And if sailing gave much to Robin Knox-Johnston in 1968, in the fifty years since he has re-paid it a thousandfold"

But as to re-enacting as far as possible the Gold Globe challenge of fifty years ago, it’s something which can evoke reservations among sailors. Re-enactments are difficult enough ashore, but the re-staging of a round the world solo sailing “race” of half a century ago, with an insistence that the boats be not more than 36ft long and of traditional “closed form” type (ie with rudder hung on the back of the keel), plus additional limitation on modern equipment – well, it all begin to make it all seem a bit artificial, rather than a simple return to good old-fashioned basics.

Nevertheless, with the prospect of at least 270 days at sea and the inevitability of sailing on some of the roughest waters in the world, this is a mighty challenge and then some, and Irish adventurer Gregor McGuckin has thrown his hat into the ring with his entry of a Biscay 36 called Mary Luck.

Gregor McGuckin with his Biscay 36 showing exactly the hull shape which is mandatory for the Golden Globe 2018.

Gregor McGuckin with his Biscay 36 showing exactly the hull shape which is mandatory for the Golden Globe 2018.

Gregor McGuckin’s Mary Luck. The Biscay 36 was designed by Alan Hill in 1974, when her closed-form hull profile was already being superseded by fin-and-skeg yachts

Gregor McGuckin’s Mary Luck. The Biscay 36 was designed by Alan Hill in 1974, when her closed-form hull profile was already being superseded by fin-and-skeg yachts

When something as big as this is in prospect, extravagant claims are not helpful, but his supporters are right in claiming that he will be the first Irishman to sail solo non-stop around the world. For as Cape Horn solo veteran Pete Hogan has gently pointed out, Bill King of Oranmore with Galway Blazer II in 1973 was first Irish man to go solo past Cape Horn with Galway Blazer II in 1973, but he had stopped for repairs in Australia. However as the fleet gathers in Les Sables d’Olonne for the start on July 1st (for apparently British ports were disinclined to host it), who or what or when as regards previous circumnavigations will not be top of the agenda, for it will be dominated by this one extraordinary challenge being faced by all entrants.

Bill King of Oranmore on Galway Bay circumnavigated the world solo in 1973 on Galway Blazer II.

Bill King of Oranmore on Galway Bay circumnavigated the world solo in 1973 on Galway Blazer II.

Yet in the Irish sailing context, Gregor McGuckin’s gallant campaign is just one of many solo efforts which deserve our special attention simply because of the solitary nature of what is involved. We may already have mentioned Annalise Murphy, Aoife Hopkins and Fionn Lyden in the Olympic context, but there are also Oisin McClelland in the Finn, and Finn Lynch in the Laser

Leading the charge. Finn Lynch of the National YC doing what he does best, with the British and Russian boats tucked astern.

Leading the charge. Finn Lynch of the National YC doing what he does best, with the British and Russian boats tucked astern.

As for the offshore stuff, we’re still digesting the extraordinary achievement of Enda O Coineen in getting back alone to Les Sables d’Olonne from New Zealand at the beginning of the month, but equally let us remember that while Tom Dolan races off for the Caribbean with his best shipmate, back in France Joan Mulloy of Westport is continuing with her determination to bring herself up to speed in sailing solo in the Figaro.

Then too, up among the IMOCA 60s, Nin O’Leary of Crosshaven has his developing programme which points inevitably to the next Vendee Globe, in which Alex Thomson’s campaign with Hugo Boss will be receiving continuing input from Stuart Hosford in Cork.

All these sailors come up on the radar because they’re in the world of racing. But solo cruising continues to be a significant interest, and sometimes you hear of lone Irish sailors turning up unexpectedly in out-of-the way places, and then slipping away with even less fuss. They’re all different, these single-handers, whether racing or cruising. And for those of us who sail sociably, they and their achievements have a special fascination.