There is a monumental singularity of achievement in Robin Knox-Johnston’s non-stop solo voyage around the world in the 32ft Suhaili fifty years ago. While there may have been others taking on the Golden Globe Challenge set by The Sunday Times in 1968 – in some cases with tragic results – the simple fact that Suhaili did it, and did it so well, stands out like a magnificent lighthouse above the turbulent seas of all subsequent global sailing experience writes W M Nixon

Some might argue that the Knox-Johnston success is best honoured by being allowed to stand in all its glory, isolated and serene. But modern society’s endless need for fresh excitement and new entertainment makes us incapable of leaving well alone. The thought of the Golden Jubilee of the Golden Globe is irresistible, and on July 1st, 18 yachts of a certain size and vintage, all sailed solo by a dozen different nationalities, will set out from Les Sables-d’Olonne on France’s Biscay coast to race and replicate Suhaili’s 30,000 miles voyage.

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston on his battered but unbowed Suhaili hears for the first time in the final approaches to Falmouth that he has won the Golden Globe

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston on his battered but unbowed Suhaili hears for the first time in the final approaches to Falmouth that he has won the Golden Globe

It is Challenge Plus, as the participants are not only limited to boats no more than 36ft long from a past era, of closed hull profile with the rudder attached to the trailing edge of the keel, but they must largely use the technology of that period. At its most basic, this means non-electronic navigation by sextant and paper charts. If they have to use any more modern communication equipment other than within strict limits, they are automatically disqualified.

Originally the idea of Australian adventure promoter Don McIntyre, the concept has taken hold internationally thanks in part to the actively promotional port of Les Sables-d’Olonne in France, which continues its reputation of developing ideas for great ocean projects by using the idea for yet another major attention-getting race for which there has been worldwide interest, attracting an extraordinary diversity of entries.

Among them will be Ireland’s Gregor McGuckin in his vintage Biscay 36 Hanley Energy Endurance, first reported by Afloat.ie back in December 2015. While he is an experienced sailor with Transatlantic voyages in his CV, at a gathering this week at the National YC in Dun Laoghaire to see his boat in her final stages of race preparation while finding out more about the man himself, he admitted that he has never spent more than two weeks entirely alone, and has never before undertaken a solo ocean voyage.

As it happens, when Conor O’Brien of Foynes departed from Dublin Bay in June 1923 to undertake his pioneering circumnavigation south of Good Hope and Cape Horn with the fully-crewed Saoirse - and with stops at various ports in mind - neither he nor his little 42ft ship had ever undertaken an ocean sailing voyage before. Yet in the fullness of time, they did it, and inspired others to follow.

But although much has been experienced along the same route since, the fact remains that the Great Southern Ocean is an immense and merciless force of nature which takes no prisoners. In a sun-soaked Dun Laoghaire this week, with the only wind a welcome, gentle and cooling nor’east sea breeze, it was well-nigh impossible to imagine those grey and trackless wastes, where the Southern Hemisphere’s highest-ever recorded sea wave was measured last month by a weather buoy south of New Zealand, clocking in at 19.4m, which 64ft in old money.

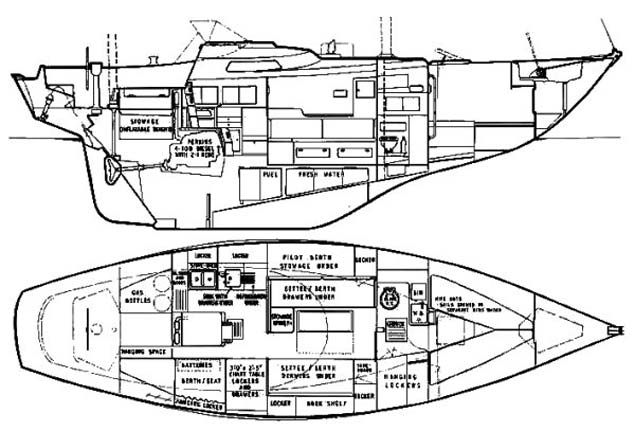

Biscay 36 hull profile. The rules of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Challenge stipulate that the boat is between 32 and 36ft long, and designed pre-1988 with the rudder attached to the trailing edge of the keel.

Biscay 36 hull profile. The rules of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Challenge stipulate that the boat is between 32 and 36ft long, and designed pre-1988 with the rudder attached to the trailing edge of the keel.

That’s “Standard Wave” measurement. Rogue waves can go much higher, and steeper ones have been recorded where ocean and land interact more directly, with our own North Atlantic serving up some world champions. But the essence of the Southern Ocean is its relentless procession of rolling giants, whose every breaking crest can be boat-breakers for the unprepared.

Yet the very fact that so many boats – relatively speaking – have now circumnavigated the world by the southern route makes this new take on the challenge irresistible, and many of those involved - including Gregor McGuckin – have been working on their campaigns since 2016 and earlier. But while the Irish sailor went at it from a standing start with little in the way of resources, and had to work an exceptionally busy Caribbean charter season and a programme of lucrative deliveries in order to build up the beginnings of a war chest, more seasoned challengers started from a position of strength.

Few were better placed than the most senior entrant, 72-year-old French long-distance racing legend Jean-Luc Van Den Heede, well-resourced to begin with, and always with new supporters available. His research quickly told him that the boat which provided optimum performance for the challenge while fitting the entry constraints of 32-36ft long, and designed pre-1988, was the British-built 1980 Holman & Pye-designed Rustler 36, of which just over a hundred were built in southwest England.

The sloop-rigged Rustler 36 – a design of 1980 – is the most-favoured boat type for the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee

The sloop-rigged Rustler 36 – a design of 1980 – is the most-favoured boat type for the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee

By 2016, Van Den Heede was in a training and tuning programme off Brittany and in the Bay of Biscay with his Rustler 36 Matmut, named for the French insurance company who are his main sponsors. His choice of boat has since been flattered by being followed by five other entries, such that the current fleet breakdown from for the July 1st start is six Rustler 36s, three Biscay 36s, two Tradewind 35s, two Endurance 35s, and one each Benello Gaia 36, Lelloe 34, Nicholson 32, QE32, and a Suhaili replica.

In terms of line honours, the Rustler 36s have to be the favourites, for although their keel/rudder/propeller aperture configuration may make them – like the Biscay 36 – something of a challenge to manoeuvre under power in a hyper-confined marina space, that is not a problem in the open ocean where their potent sloop rig and slippy hull must give them an edge over the ketch-rigged Biscay 36.

Yet such was the nostalgia for Suhaili’s achievement of 1968-69 that the original reaction to the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee challenge was the expectation that robust ketches would be the backbone of the fleet. And in any case, even a much-used Rustler 36 - seen as a “modern classic” – was beyond Gregor McGuckin’s budget, whereas he was able to find an affordable Biscay 36 – Mary Luck – in Portrush in Northern Ireland, and the show was on the road.

The standard Biscay 36 Mary Luck in the throes of transformation in Malahide, making her into the Golden Globe challenger Hanley Energy Endurance.

The standard Biscay 36 Mary Luck in the throes of transformation in Malahide, making her into the Golden Globe challenger Hanley Energy Endurance.

McGuckin’s own progression into high end sailing is unusual, for although he is from Dundrum in south Dublin, it was while at the College of Further Education in Coolock in the north of the city that he was introduced to sailing on the Broadmeadow Water in Malahide, and his fascination with the challenge of outdoor life was reinforced by six years of living it in Mayo before he went more seriously into fulltime sailing with the emphasis on the Caribbean, where he rose to become the skipper of a 62 footer.

Thus there’s a satisfying circularity in the fact that his newly-acquired Biscay 36 was brought back to Malahide for the very complete refurbishment and programme of modifications which are essential to have her race ready for he Golden Globe Challenge. And though she is now a boat transformed, it was still a case of work in progress on Thursday of this week as the reassuring presence of Neil O’Hagan of Team Ireland – the Enda O Coineen organisation – hosted a Gregor McGuckin reception for press and supporters alike at the National YC.

The change of use from coastal cruiser to ocean challenger, and the endless work list is evident in the saloon. Photo: W M Nixon

The change of use from coastal cruiser to ocean challenger, and the endless work list is evident in the saloon. Photo: W M Nixon

While Hanley Energy have been main sponsors since June 1st, support has been welcome wherever it can be found……Photo W M Nixon

While Hanley Energy have been main sponsors since June 1st, support has been welcome wherever it can be found……Photo W M Nixon

In a question and answer session, Gregor was in such good form that I asked him how much sleep he’d had the night before, and the answer with a smile was three hours….The jobs list keeps relentlessly increasing, while the need for increased sponsorship had always been there until lead supporters Hanley Energy came on board on June 1st. Whereas in France the concept of something like the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee – and the association with Les Sables d’Olonne – will lead to almost instant recognition from those who need to know, in Ireland you sometimes have to start completely from scratch.

That said, the work programme in Malahide attracted an increasing team of dedicated supporters and voluntary specialists – some very highly skilled indeed - with the Cruising Association of Ireland, in particular, being more than helpful. And though Hanley Energy may have been in support for a relatively short time, on the pontoon at the National YC their MD Dennis Nordon left us in no doubt of the fullness of that backing, and in all it was clear that when Gregor gets to Les Sables, there’ll be plenty of supporters on site to help him make final preparations for the start.

Gregor McGuckin demonstrates his skills with the sextant – all ocean navigation is to be by sextant and paper charts. Photo: W M Nixon

Gregor McGuckin demonstrates his skills with the sextant – all ocean navigation is to be by sextant and paper charts. Photo: W M Nixon

This Saturday morning, Hanley Energy Endurance is at sea, sailing south to Falmouth to join next week’s Golden Jubilee celebrations around Robin Knox-Johnston and Suhaili, for, despite the central role now played by Les Sables-d’Olonne, it was in Falmouth that Suhaili started and finished her great voyage half a century ago.

So in a decidedly crowded programme, Thursday’s gathering provided a brief opportunity for stock-taking on the changes that have taken place with the boat. This I found of special interest because way back in the previous Millennium – in 1976 to be precise – I did a sail test on one of the first production Biscay 36s for Yachting World magazine, with which I worked for a quarter of a century as a sort of freelance Columnist at Large.

The 1975-built Biscay 36 Vizcaya at Falmouth in 1976. She is entered in the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Challenge 2018 by Antoine Cousot of France. Photo: W M Nixon

The 1975-built Biscay 36 Vizcaya at Falmouth in 1976. She is entered in the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Challenge 2018 by Antoine Cousot of France. Photo: W M Nixon

Test-sailing a Biscay 36 off Falmouth, April 1976. Extra weight was later added to the ballast keel. Photo: W M Nixon

Test-sailing a Biscay 36 off Falmouth, April 1976. Extra weight was later added to the ballast keel. Photo: W M Nixon Biscay 36 on a fast reach in Falmouth Bay, April 1976. Photo: W M Nixon

Biscay 36 on a fast reach in Falmouth Bay, April 1976. Photo: W M Nixon

Most appropriately, in yet another instance of the circularity of this story, that sail test took place in Falmouth Bay. The Alan Hill-designed boats were being built by Falmouth Boat Construction Company using fibreglass mouldings by Robert Ives, and were aimed at a market seen as “people who would really like a completely wooden boat if they could only afford the maintenance”.

The test took place in a brisk but sunny April easterly with Brian Reynolds and his team from the builders. This guaranteed a congenial day’s sailing in a handsome and generally very attractive boat whose only flaw was a certain tenderness when hard on the wind, but Gregor was telling me that later models saw a significant increase in the amount of moulded-in ballast keel, which has made her stiffer.

As to the boat generally, she’d a very workable and seamanlike layout on deck and comfortable below. While a ketch rig is not everyone’s preference – particularly in a boat only 36ft long – she seemed all of a piece, the sails were easily handled, and in all she struck me as a handy vessel which was easy on the eye and a pleasure to be aboard.

The mainmast rig in 1976 was the essence of simplicity……Photo W M Nixon

The mainmast rig in 1976 was the essence of simplicity……Photo W M Nixon …..but in 2018, the mainmast has two sets of spreaders and other extras. Photo: W M Nixon

…..but in 2018, the mainmast has two sets of spreaders and other extras. Photo: W M Nixon

But while she was well able for offshore and ocean cruises – several have crossed the Atlantic – the Southern Ocean is something else altogether, and the work programme in Malahide has seen everything from extra hull reinforcement to the upgrading of all chainplates and their bases, the re-vamp of the masts, spars and rigging, the installation of many safety features such as a massive waterproof door where formerly there would only have been sliding planks in the companionway, and the addition of a notably strong “rigid sprayhood” over the companionway.

The new storm door in the companionway speaks volumes of the challenges which will be faced, as does the new rigid sprayhood. Photo: W M Nixon

The new storm door in the companionway speaks volumes of the challenges which will be faced, as does the new rigid sprayhood. Photo: W M Nixon

This new structure is high-vis orange, so with the new dark green hull and the remaining white deck and superstructure, we have a boat which is sailing in the colours of Ireland’s national flag. Such a thought would have been a long way from anyone’s minds in Falmouth Harbour in 1976, where the 1975-built Biscay 36 sister-ship Vizcaya lay to moorings nearby. And equally, it would have been beyond imagination in 1976 to visualise that in 2018, Vizcaya would be an entry in the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Challenge, raced by 47-year-old Antoine Cousot of France.

The hull has been internally reinforced forward. Photo: W M Nixon

The hull has been internally reinforced forward. Photo: W M Nixon

Living on enthusiasm and very little sleep – Gregor McGuckin aboard Hanley Energy Endurance in Dun Laoghaire on Thursday. Photo: W M Nixon

Living on enthusiasm and very little sleep – Gregor McGuckin aboard Hanley Energy Endurance in Dun Laoghaire on Thursday. Photo: W M Nixon

Cousot’s age is not far off the average for the skippers, which makes Gregor McGuckin at 31 one of the youngest involved. And he’s facing into a challenge in which, if all goes well, he’ll be on his own for around 270 days. But as educational linkups have been arranged so that Hanley Energy Endurance’s progress can be followed by primary schools back home in Ireland, he’ll know that others are thinking of him.

Nevertheless, the challenge of a long time alone and total self-reliance is ultimately what it’s all about. But as Gregor remarked on Thursday, managing to get to a position where they really do feel alone is seen by many skippers as the first major hurdle that has to be crossed. Getting away from Les Sables-d’Olonne and out into shipping-free clear water beyond Cape Finisterre in northwest Spain is much more of a challenge for relatively slow boats like the Golden Globe contenders than it is for the flying machines in the Vendee Globe.

Whatever way it goes, the thoughts of many in Ireland will be with him. And if it goes well, he will definitely be the first Irishman to sail solo around the world non-stop.

A Biscay 36 transformed. While Handley Energy Endurance is race number 22, dropouts mean that 18 boats are now expected to start on July 1st. Photo: W M Nixon

A Biscay 36 transformed. While Handley Energy Endurance is race number 22, dropouts mean that 18 boats are now expected to start on July 1st. Photo: W M Nixon

It’s not every day you get your photo taken by one of the nation’s leading poets – Gregor McGuckin and Winkie Nixon as recorded by Theo Dorgan at Thursday’s Golden Globe Jubilee gathering. Photo: Theo Dorgan

It’s not every day you get your photo taken by one of the nation’s leading poets – Gregor McGuckin and Winkie Nixon as recorded by Theo Dorgan at Thursday’s Golden Globe Jubilee gathering. Photo: Theo Dorgan