For those of us who find historical re-enactments to be slightly spooky, following the twists and turns of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Race through the latter half of 2018 and into the early months of 2019 has been - for want of a more appropriate phrase - a mildly disturbing experience writes W M Nixon.

The ultimate nature of what the participants were undertaking was utterly genuine. And in many cases, they had to draw very deeply on their own resources, and on bottomless wells of sheer courage, which the rest of us could barely imagine. Yet the complex business of using a re-enactment of a great seafaring achievement from all of 50 years ago, in order to capture attention nowadays and provide contemporary entertainment through this ultimate seafaring challenge – well, it just felt a bit unsettling.

There was an air of the stadium-staged gladiatorial contest about it which seemed to be at variance with the straightforward reality of lone sailors battling against the most vicious moods of the great oceans of the world. There was a slight whiff of exploitation. Yet beyond the unease was the realisation yet again of the totally unique beauty of what Robin Knox Johnston achieved with his 32ft own-built ketch Suhaili in 1969.

Robin Knox-Johnston sailing Suhaili in 2018

Robin Knox-Johnston sailing Suhaili in 2018

For sure, there had been Joshua Slocum in 1895 and Conor O’Brien in 1925 before him, pioneering the solo global circumnavigation and the circuit south of the great Capes.

But the voyage of the Suhaili has its own clearcut quality, reaching such a degree of perfection in being the first non-stop global circumnavigation that it seemed its greatest honour would lie in being left undisturbed, to be honoured in revered memory.

Of course, with the passage of time, there have since been other non-stop circuits, usually in larger and conspicuously more expensive craft which reach their apogee today in the IMOCA 60s and the Vendee Globe, such that non-stop global solo circuits are now almost entirely a matter of highly-competitive racing.

But even though Suhaili was in theory taking part in a race, it was a very disparate affair, and her skipper’s achievement became a standalone feat, its singular beauty enhanced by its recollection through the passing of the years. Yet the fact is that those of us who feel that something like this is best honoured simply by being remembered with respect are probably in a minority – and a small minority at that.

With the approach of the Golden Jubilee – fifty years since the first and only Golden Globe challenge - there were at least as many people who felt that a full-on re-enactment was a reasonable idea, and the organisers set about putting it in place.

By now we are all well aware of how the attempts to achieve retro authenticity by severe restrictions on navigational and communication aids put extra pressure on the participants. But better known is how the attempt to restrict boats to “something similar to Suhaili” went slightly astray. The requirement was for boats of “closed profile”, designed no later that 1988, of fibreglass construction with a minimum of 20 boats built from the mould, and with an overall hull length between 32ft and 36ft.

Gregor McGuckin’s Biscay 36 at the start of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee, 1st July 2018. Professional sailor/adventurers such as McGuckin saw the race as an affordable opportunity to move into a higher level of competition and recognition

Gregor McGuckin’s Biscay 36 at the start of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee, 1st July 2018. Professional sailor/adventurers such as McGuckin saw the race as an affordable opportunity to move into a higher level of competition and recognition

Initially, people thought of boats very broadly similar in type to Suhaili, with ketch rig. One who went down this route was our own Gregor McGuckin, a hugely experienced sailor with many Atlantic delivery crossings in his CV. He went for a Biscay 36 ketch designed in 1974 by Alan French, and put heart and soul into her preparation, as he saw the Golden Jubilee Golden Globe as offering a rare and affordable chance to step up to a higher level of international sailing.

Yet even at the most basic level of preparation, it was an expensive business, even if cheap by comparison with an IMOCA 60 campaign. For all entrants, the search for sponsorship was part of the process, though some were better prepared than others. In his early 70s, the successful veteran French sailing star Jean-Luc van den Heede saw the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee as an opportunity for a swansong performance. With his proven track record, he soon had secured sponsorship from insurance company Matmut, and with first place in mind and resources in place, he was able to act on research which showed that that boat which best filled the bill of taking line honours while complying with the regulations was the Rustler 36, a Holman & Pye sloop designed in 1980.

With a transom stern and a large sloop rig, the inherently fast Rustler 36 may look old-fashioned compared to modern craft. But she is light years away from William Atkin’s 1932 design from which Suhaili had been built, and when the fleet came to the line off Les Sables-d’Olonne on July 1st, Rustler 36s made up the largest group in the fleet, and soon were making much of the running.

Jean-Luc van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Matmut, winner of the 2018-2019 Golden Jubilee Golden Globe

Jean-Luc van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Matmut, winner of the 2018-2019 Golden Jubilee Golden Globe

Yet neither they nor any other boats racing could remotely match the pace being set by Jean-Luc van den Heede in Matmut, and by the time he was passing Australia, he was well over a thousand miles in the lead, making it all seem like a walk in the park. Admittedly he experienced serious rig problems later in the race, but his overall win was richly deserved.

However, boats further down the fleet experienced insuperably rough weather in the Southern Indian Ocean. Gregor McGuckin and Abilash Tomy were within ninety miles of each, and both were rolled in a 90-knots-plus superstorm which left them dismasted.

In all, five boats out of the 17 starters were dismasted through a variety of rolling experiences in the Southern Ocean. This is an outcome which has led Robin Knox-Johnston into further researches whose conclusions were published on Monday of this week, and he quotes a US Coastguard report which indicates that being rolled or pitch-poled is a function of breaking wave height relative to boat length. This section of the report reads in full:

“The Southern Ocean is the only expanse of ocean that goes all the way around the world with no land in the way The result is that the depressions, which drive the winds and therefore the waves, have nothing to stop their development which leads to the creation of very large waves.

Recent research has shown that it is possible for rogue waves as large as 27+ metres to develop in this ocean. A rogue wave is defined as a wave that is twice the significant wave height, usually steeper and frequently reported as a wall of water. The force of these waves can be extreme. A 12-metre wave has a breaking pressure of about 6 metric tons per square metre, whereas a rogue can produce a pressure of up to 100 metric tons per square metre.

A very interesting United States Coastguard (USCG) study concludes that storm waves are generally not regular or stable, and individual waves do not hold their shape for very long. It indicates that the white water height of a breaking wave will have to be at least half the LOA of the boat for the boat to be rolled. This means that even a comparatively small 6 metre high breaking wave could roll the average boat of 36 feet length.

Thus the larger the boat the less susceptible it is to being rolled. Also, the larger modern boats like Open 60 class yachts are light with large sail areas and can usually outpace a wave which a heavier, smaller yacht cannot do.

An artist’s impression of Suhaili in storm conditions in the Southern Ocean. From the painting by Gordon Frickers

An artist’s impression of Suhaili in storm conditions in the Southern Ocean. From the painting by Gordon Frickers

The USCG conclusion is that the danger does not come from a normal wave, but from a breaking wave regardless of the measures being taken to try and restrain the boat. That is not totally supported by some of the evidence from the experience here, although there is agreement on the danger of the breaking wave. The USCG report also suggests that a small boat in a non-breaking sea moves more or less with the surface water so will not be struck by the mass of moving water and therefore will be less likely to be capsized. So lying a-hull may work up to the point where the waves start to break. However, the water in a breaking wave at its crest moves much faster and can strike a boat at a speed of as much as 20 knots. This is confirmed by the experience of most reports of knockdowns in this race where the sound of the approaching breaking wave was heard before it struck.

The famous 26-metre rogue wave that struck the Draupner Oilfield Platform in the North Sea on 1st January 1995 has been replicated in the laboratory by Oxford and Edinburgh Universities. The evidence from these tests indicate that when waves are crossing each other at an angle of 120 degrees they could create the occasional giant wave. The conditions for this type of wave occur in the Southern Ocean.

A recent paper published jointly by the National Oceanography Centre and University of Southampton has concluded that Global significant wave heights have increased over the past 30 years, but occur less often.”

With such experiences being reported at mid-race and then conclusions like this being drawn in the post-race analysis, you might have thought that the organisers would have long since been reflecting that enough is enough - a commemoration every fifty years would more than adequate to be going along with. But not a bit of it. On the contrary, the Golden Jubilee Golden Globe Race wasn’t long underway before it became clear that another similar race was planned for four years time in 2022, and a list of interested sailors was already taking shape.

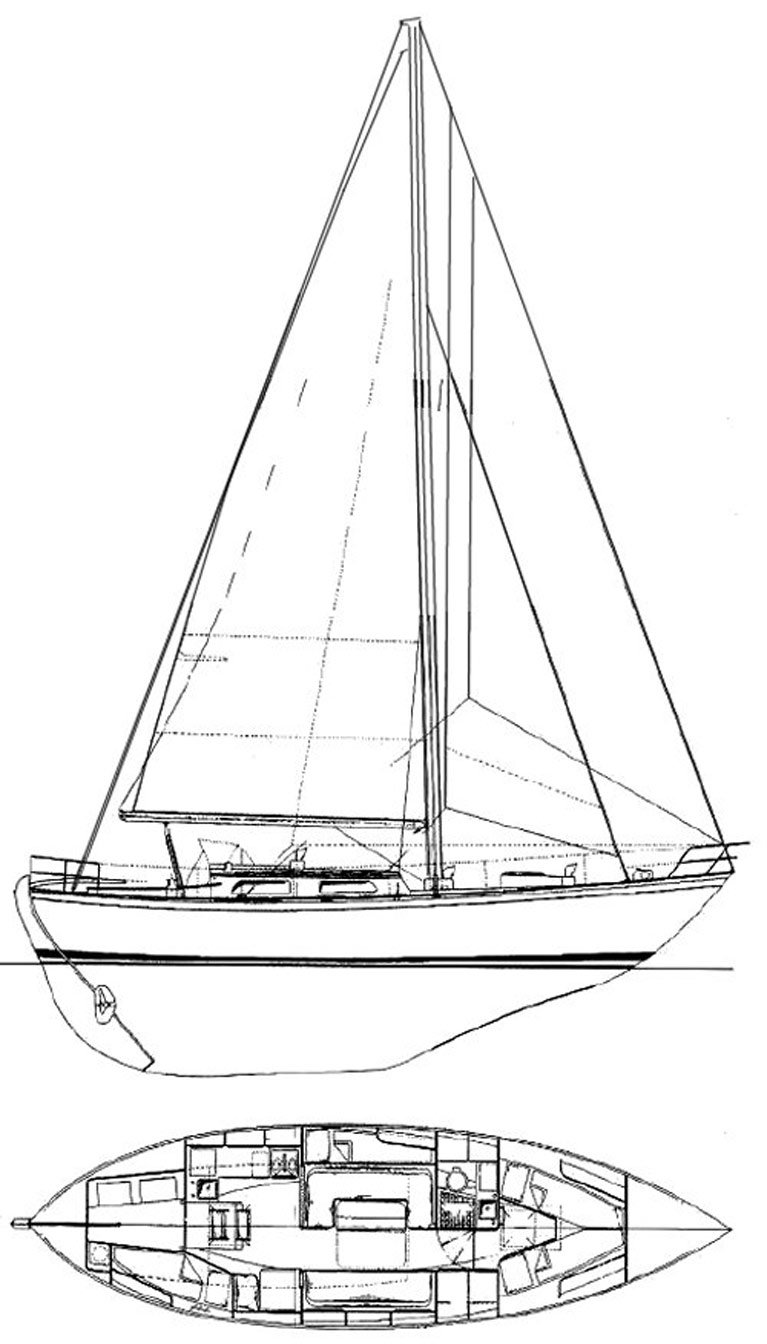

The new Joshua One-Design – ten will race in the 2022 Golden Globe

The new Joshua One-Design – ten will race in the 2022 Golden Globe

Not only that, but since August 2017 organiser Don McIntyre had been promoting the concept of a One Design Class within the 2022 race. It was not to be a One Design based on Suhaili - as you might have expected - but one based on Joshua, with which Bernard Moitessier had been fourth to start, more than two months after Robin Knox Johnston, in the original Golden Globe in 1968.

With this week’s wrap-up of the 2018 race being published, it was again stated that the 2022 fleet will be in two sections. There’ll be the mixed division for which Pat Lawless of Dingle has already put his name down with his Alan Pape–designed Saltram Saga 36.

The Alan Pape-designed Saltram Saga 36 – Pat Lawless of Dingle has entered one for the 2022 Race

The Alan Pape-designed Saltram Saga 36 – Pat Lawless of Dingle has entered one for the 2022 Race

But there’ll also be this new strictly One Design Class of ten steel-built boats, constructed in Turkey and based on Moitessier’s 39ft Joshua, which was fourth away in 1968’s race and was a potential contender, but her skipper slipped into a very philosophical frame of mind and retired into the Pacific islands.

It was a French way of looking at seafaring competition which is very much at variance with their full-on competitions today, such as the Vendee Globe and the Figaro. Yet some top modern French sailors have some of the Moitessier philosophy in their make-up. After his impressive win in November 2017’s Mini Transat, 20-year-old Erwan le Draoulec admitted that he hadn’t really enjoyed the actual sailing, triumphant as it had been. He said that he felt he was abusing the Atlantic in sailing across it just as fast as humanly possible for 6.5 metre boat, and that at some time in the future, he would look forward to sailing across the ocean in a more gentle and contemplative style.

Erwan le Draoulec (21). The youthful winner of the Minitransat in November 2017 crossed the ocean so quickly he reckoned it was an abuse of the Atlantic

Erwan le Draoulec (21). The youthful winner of the Minitransat in November 2017 crossed the ocean so quickly he reckoned it was an abuse of the Atlantic

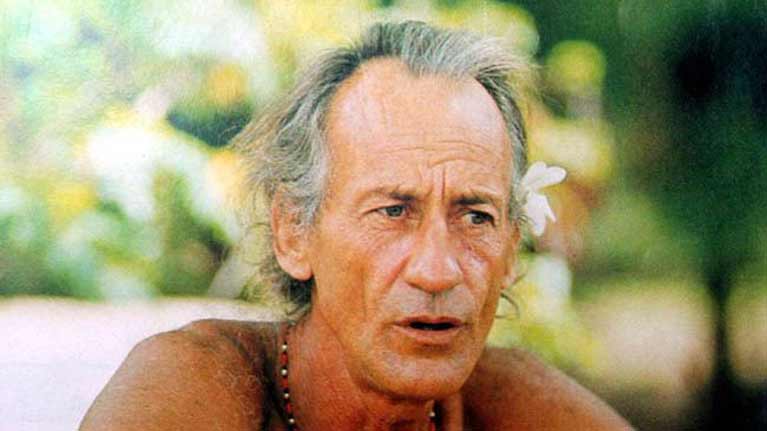

In the end, Bernard Moitessier (1925-1994) also came to a fresh view of what he was doing, but his change of heart came in mid-race. Alone on the ocean and in the lead, he found he was rejecting what he saw as the commercialisation of long distance sailing, and pulled out of the race to voyage among the Pacific islands. Yet it seems that in 2022, a certain level of commercialisation will revive memories of what he did. Like it or not, there seems to be a growing demand for re-enactments.

The sailor-philosopher. Bernard Moitessier (1925-1994) in thoughtful mood in his beloved Pacific islands

The sailor-philosopher. Bernard Moitessier (1925-1994) in thoughtful mood in his beloved Pacific islands

29/4/19: 7 pm: This article has been updated in light of Barry Pickthall's comments (below) - our thanks to him.