Three million euro - every bit of €3 million writes W M Nixon. That’s what the late Theo Rye, internationally-recognised expert on the restoring and re-building of classic and traditional craft, reckoned that breathing new life into Ireland’s historic 56ft trading ketch Ilen would have cost – at the minimum - if the project had been awarded on a fully professional basis to some comprehensively equipped, properly qualified and economically efficient specialist boatyard in the heartlands of the top end of boat-building skills, in places such as The Netherlands, or at select yards around the Solent, or somewhere up in Denmark.

However, the restoration of the 1926-built Ilen, in a joint effort by the Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick and Liam Hegarty’s Oldcourt Boatyard near Baltimore, has certainly produced a fully restored little ship which exudes quality and authenticity. But thanks to special efforts by all involved, there is no way that the cost has been remotely near that jaw-dropping figure of €3 million.

Yet while the sums have been much more manageable, every cent of it has had to be secured from one source or another, and by this stage Gary Mac Mahon of Limerick – the inspiring overall promoter of the Ilen ideal – can probably fill out grant applications and benevolent funding proposals in his sleep.

Captain Gerry Burns, shipwright Liam Hegarty and Ilen Project Director Gary MacMahon at the Ilen reception in the Royal Irish YC. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Captain Gerry Burns, shipwright Liam Hegarty and Ilen Project Director Gary MacMahon at the Ilen reception in the Royal Irish YC. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Now, however, the fact that Ilen is in full seagoing commission and properly certified - following her annual inspection by official specialists in Baltimore a fortnight ago - gives people something very tangible to grasp when support is sought.

Rather than the high-flown but inevitably vague talk of times past, and thoughts of increasing respect for Ireland’s sometimes hidden maritime traditions while also honouring the memory of Conor O’Brien whose seafaring achievements directly resulted in Ilen being built in the first place, we now have something real. A proper little ship with which we can all identify. A little ship which nevertheless still needs a steady flow of real money to keep up the good work of adding interest to international school projects, implementing programmes like Sailing Into Wellness, and giving extra meaning to environmental campaigns.

Thus last weekend’s extended visit to Dublin, with target points for shoreside interactions with well-wishers at Poolbeg Yacht and Boat Club in the Liffey, the Royal Irish Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire, and the heart of Howth Harbour during the annual Prawn Festival, were all occasions with multiple purposes.

When the Ilen arrived at her berth at the RIYC, it had only recently stopped raining, but by the time the reception got underway, the sun was shining. Photo: W M Nixon

When the Ilen arrived at her berth at the RIYC, it had only recently stopped raining, but by the time the reception got underway, the sun was shining. Photo: W M Nixon

At its most basic, there was the opportunity for people who had a vague feeling of goodwill towards the ship to actually see her and go aboard. Then for those who knew something of what the restored Ilen really meant, there was an opportunity to inspect and wonder at the quality of the restoration, and the skills of creative design which have been used to turn a little freight and ferry ship into a proper long distance voyager with comfortable crew accommodation, yet with enough space to be a floating classroom.

This weekend, Ilen is the star of the annual Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival. But while many memories are vivid from last weekend’s time in Dublin, there’s no doubt the highlight was the re-launch ceremony at the Royal Irish Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire, a club with which the Foynes Island sailor Conor O’Brien from County Limerick had special links.

A seriously traditional ship – Ilen at the RIYC berth with the sun coming through and visitors beginning to flock on board. Photo: W M Nixon

A seriously traditional ship – Ilen at the RIYC berth with the sun coming through and visitors beginning to flock on board. Photo: W M Nixon Ilen’s localised area of sunshine lasted for most of the reception at the RIYC. Photo: Deirdre Power

Ilen’s localised area of sunshine lasted for most of the reception at the RIYC. Photo: Deirdre Power

However, as this interaction was at its height in the 1920s, it’s clear that for many of today’s sailors, knowledge of O’Brien and his achievements are vague in the extreme, so the background to the story provides a useful context for the speech of welcome and encouragement which came from RIYC Commodore Joe Costello.

RIYC Commodore Joe Costello welcomes the Ilen back to his club’s fleet after an absence of 93 years. Photo: Deirdre Power

RIYC Commodore Joe Costello welcomes the Ilen back to his club’s fleet after an absence of 93 years. Photo: Deirdre Power

Conor O’Brien of Foynes Island in the Shannon Estuary in County Limerick lived from 1880 to 1952. A grandson of William Smith O’Brien of the Young Ireland movement, he was firstly a mountaineer who then became a pioneering ocean voyager when he was the first amateur sailor to circumnavigate the world south of the Great Capes including, of course, the legendary Cape Horn.

Conor O’Brien at the helm of Saoirse during the 1923-1925 round the world voyage, which began and ended at the RIYC

Conor O’Brien at the helm of Saoirse during the 1923-1925 round the world voyage, which began and ended at the RIYC

He did all this in 1923-1925 in the little 42ft gaff ketch called Saoirse, which he designed himself and had built by Tom Moynihan and his master shipwrights in Baltimore in West Cork. She was called Saoirse – “Freedom” as it is in English - to celebrate the establishment of the Irish Free State, of which he was a strong supporter – so much so, in fact, that he had aided Erskine Childers in the Howth gun-running of 1914, although he and Childers took opposing sides on the acceptance of the post War of Independence Treaty of 1921.

O’Brien withdrew from active political involvement, and instead devoted himself to getting his ideal of an ocean voyaging vessel built in Baltimore in 1922. Although he claimed that, in the first place, all his voyages really started and finished at his home port of Foynes Island, officially it was from his club, the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire on the 20th June 1923, that Saoirse’s great voyage got under way. And exactly two years later, on Saturday, June 20th 1925, Conor O’Brien and his little ship returned in triumph to this same spot, his magnificent voyage achieved.

Being a Saturday, Dublin Bay Sailing Club would normally have had a full racing programme in action. But in honour of O’Brien’s return, they cancelled racing, and their fleet provided Saoirse with a Guard of Honour as she returned to the harbour. Dublin Bay Sailing Club do not take such cancellations lightly – this was a very signal honour.

One unexpected outcome of the voyage was that when Saoirse had put into the Falkland Islands after rounding Cape Horn and sailing non-stop from New Zealand, the islanders were so impressed with the little ship’s seaworthiness that they advocated that they should have a larger version to be their inter-island ferry and freight vessel.

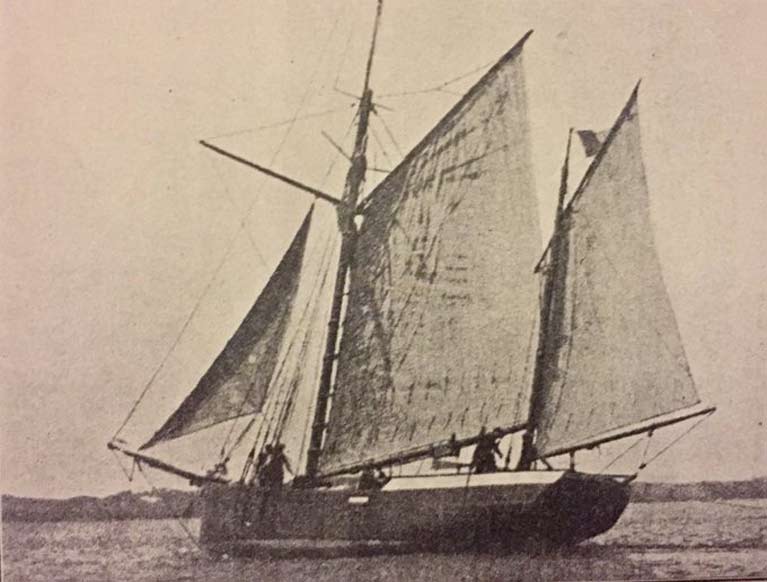

The newly-built Ilen sailing in Baltimore Harbour in 1926. Photo: Alice Foy

The newly-built Ilen sailing in Baltimore Harbour in 1926. Photo: Alice Foy

The result was that in 1926, Conor O’Brien found himself working again with Tom Moynihan in Baltimore, this time to create the 56ft ketch Ilen, which was undoubtedly Saoirse’s bigger sister.

Conor O’Brien personally delivered Ilen to the Falklands in 1926, crewed by two Cape Clear men, Con and Denis Cadogan. She was to give great service in those very rugged waters as a workboat for many decades, and when she was finally retired in the 1990s, Gary Mac Mahon of Limerick - who is both a Conor O’Brien enthusiast and a very considerable force of nature - decided that she should be shipped home to Ireland and restored to full seagoing condition in order to undertake voyaging with people who would benefit from such an experience, and also to remind us of our sometimes forgotten but nevertheless very great maritime traditions.

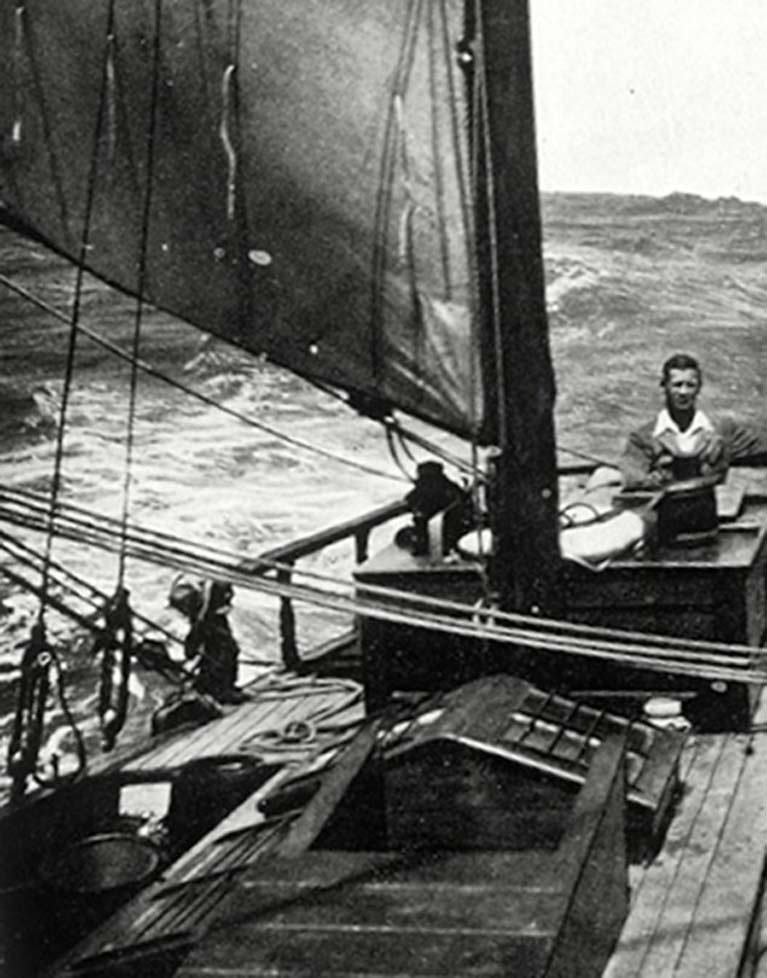

Aboard Ilen sailing in Dublin Bay in May 1998, a few months after she’d been shipped back from the Falklands. At the deckhouse and living for the moment is Tim Magennis, possibly the only person in Ireland today who has sailed round the world under gaff rig Photo: W M Nixon

Aboard Ilen sailing in Dublin Bay in May 1998, a few months after she’d been shipped back from the Falklands. At the deckhouse and living for the moment is Tim Magennis, possibly the only person in Ireland today who has sailed round the world under gaff rig Photo: W M Nixon

Tim Magennis – who recently celebrated his 90th birthday – at the RIYC after seeing the restored Ilen for the first time. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Tim Magennis – who recently celebrated his 90th birthday – at the RIYC after seeing the restored Ilen for the first time. Photo: Dermot Lynch

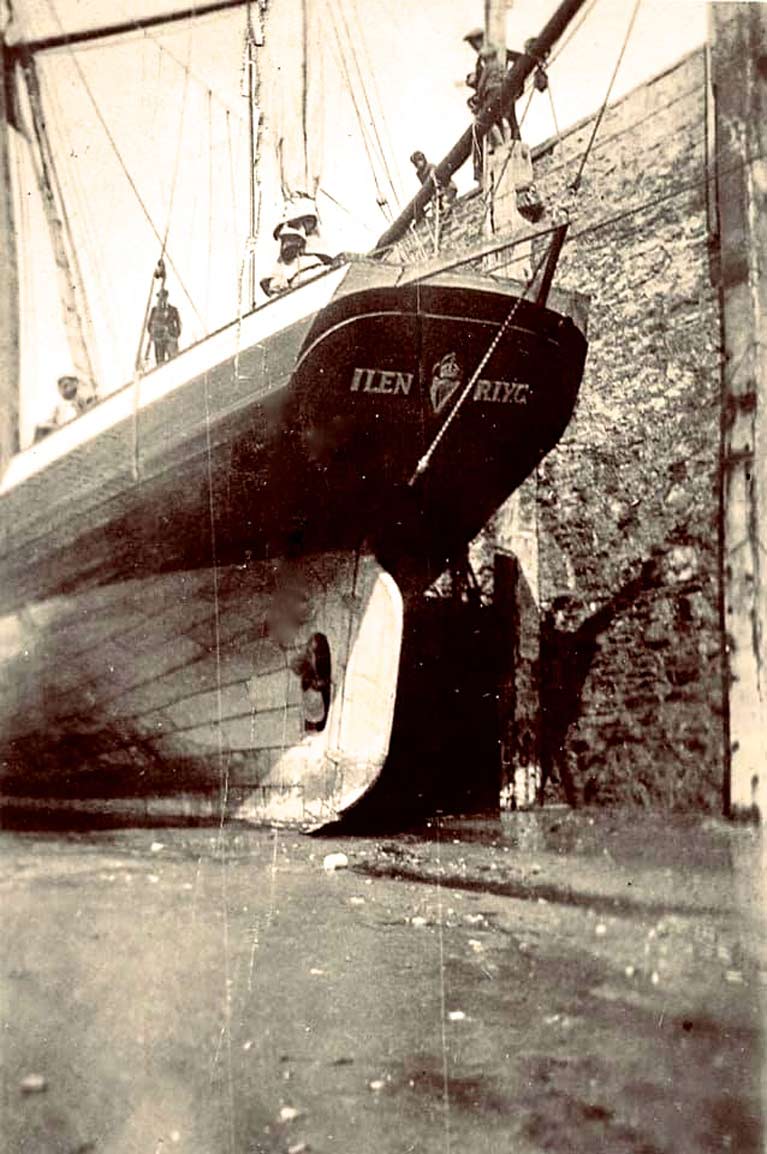

It was in November 1997 that Ilen was brought home. The fact that two decades later she was finally making her debut in this superbly restored style at the Royal Irish Yacht Club was doubly appropriate. Not only had Conor O’Brien used this as his start and finish point for his Saoirse circumnavigation in 1923-25, but when he came to deliver Ilen to the Falklands in 1926, he discovered that he was only insured as a Yachtmaster, and not as the Captain of a commercial vessel.

So when Ilen sailed out over the many thousands of miles of ocean to the Falklands, it was as part of the fleet of the Royal Irish Yacht Club – she flew the club burgee, and her club allegiance was proudly inscribed across her transom.

For six months, she was a yacht of the RIYC. Then she belonged in Port Stanley, and was a working boat. But now she is a Limerick ship. A little ship, perhaps, but undoubtedly a ship nevertheless, and a characterful one at that. She is very expressive of Conor O’Brien’s notions of what a hard-working seagoing vessel should look like, particularly in the matter of bowsprits. Like Saoirse before her, Ilen has a bowsprit which extends into the middle of next week, for that is the O’Brien way.

As we’re now in 2019, it is self-evident that the restoration of Ilen has been a long and challenging task, at times run on a shoestring. But thanks to the profound faith of Gary and his friends, Ireland has got to this remarkable stage of having a fully-certified seagoing traditional vessel which is currently in the midst of one of the very commendable Sailing into Wellness programmes,

Although Conor O’Brien had no children of his own, his relatives are spread throughout Ireland – this is his grandniece Charlotte O’Brien Delamer with Stephanie O’Brien in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Although Conor O’Brien had no children of his own, his relatives are spread throughout Ireland – this is his grandniece Charlotte O’Brien Delamer with Stephanie O’Brien in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Then in July she’ll undertake a nine week educational voyage to Greenland from Limerick in the wake of the Atlantic salmon - a timely reminder of that splendid fish’s threatened status – while at the same time strengthening links which the Ilen Network has been building up between schools in the greater Limerick area and schools in southwest Greenland.

Experienced sailors of the west – Mick Brogan (left) and Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo will play a key role in bringing Ilen back from Greenland. Photo: W M Nixon

Experienced sailors of the west – Mick Brogan (left) and Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo will play a key role in bringing Ilen back from Greenland. Photo: W M Nixon

For the Ilen is now the symbol of a broad movement which has re-kindled awareness of the unique traditional vessels of Ireland, particularly those of the Shannon Estuary and West Cork. But were it not for this wonderful vessel at the centre of it all, the entire project would lack focus.

With the extraordinary balance of talents and almost magical chemistry between Gary Mac Mahon and Liam Hegarty and their respective teams, this restoration of exceptional authenticity has been achieved, aided in no small way by the spiritual support and guidance of Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey.

Celebrating the Ilen restoration at RIYC were (left to right) Patrick Keane SC, Deirdre Kinlen, Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey, and Dr Sheila Javaepour. Photo: Donal Lynch

Celebrating the Ilen restoration at RIYC were (left to right) Patrick Keane SC, Deirdre Kinlen, Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey, and Dr Sheila Javaepour. Photo: Donal Lynch

So we now have a proper flagship for the traditional and classic boat movement in Ireland, and we have a symbol for a form of sailing which is accessible to all - as such, the Ilen Project received the warmest praise from President Michael D Higgins when he visited the ship in Limerick last October.

This high-powered support for the “Ilen Ideals” was much in evidence at Dun Laoghaire’s gathering, where the presence of Dr Edward Walsh, founder of the University of Limerick, was matched by people like former RIYC Commodore Terry Johnson, whose remarkable record of service to sailing is augmented by work he has done on behalf of sail training, the lifeboat service, and other key pillars of the maritime world.

Former RIYC Commodore and maritime multi-tasker Terry Johnson (foreground) with renowned musician Brendan Begley (left) aboard Ilen. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Former RIYC Commodore and maritime multi-tasker Terry Johnson (foreground) with renowned musician Brendan Begley (left) aboard Ilen. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Also present were people who have given much practical assistance, such as Captain Gerry Burns of Irish Ferries, who in his leave periods served as a relief captain on the training Ship Asgard II. Since Ilen went afloat again, he has been journeying to Limerick to give master-classes in ship-handling to future Ilen skippers.

Another attendee was Tim Magennis, one of the few people who has sailed right round the world under gaff rig. When Ilen sailed briefly in Dublin Bay in May 1998 after she had been shipped back from the Falklands, Tim - a stalwart of the Old Gaffers Association – was one of those on board, and now 21 years later, having recently celebrated his 90th birthday, his delight in Ilen’s restoration was a joy to behold.

Ilen Project supporter Harry Harbison, Gary Mac Mahon, and Sheila Deegan, Arts Officer of Limerick City & County Council. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Ilen Project supporter Harry Harbison, Gary Mac Mahon, and Sheila Deegan, Arts Officer of Limerick City & County Council. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Rigging expert Trevor Ross ensures that the Limerick flag is aloft and flying. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Rigging expert Trevor Ross ensures that the Limerick flag is aloft and flying. Photo: Dermot Lynch

Although Conor O’Brien had no children, many people are related to him, and among those present were Charlotte O’Brien Delamer, his grandniece, and Stephanie O’Brien, married to another O’Brien relative.

For them, restoration of the Ilen was an intensely personal matter. But it was equally clear that many folk attending the RIYC reception found it especially moving that Ilen had been restored, and had now come to visit the club which meant so much to Conor O’Brien’s sailing.

Yet she’s a busy ship. Soon it was time to move on to Howth for a visit arranged by Wally McGuirk, where on Monday morning skipper Paddy Barry took a group of trainees from the inner-city Westland Row CBS out for some sailing experience on Ilen arranged through the Atlantic Youth Trust. Then in the afternoon, it was time to depart for Baltimore with the gift of a tankful of diesel from Howth Boat Club, on down to West Cork where the Wooden Boat Festival will serve up its own quota of emotional associations.

High latitudes veteran Paddy Barry with the Ilen in Howth on Monday morning. He’ll be aboard for the entire nine weeks voyage to Greenland. Photo: W M Nixon

High latitudes veteran Paddy Barry with the Ilen in Howth on Monday morning. He’ll be aboard for the entire nine weeks voyage to Greenland. Photo: W M Nixon

As a reminder of how things have slowly but steadily progressed, here’s a video by Paul Fuller of the then recently-launched and still largely unballasted Ilen making her debut at last year’s Festival in Baltimore. Now she is in full properly-ballasted seagoing order, ready and willing for further work at home before the voyage to Greenland gets underway from Limerick in July. It’s anticipation of this which will give the Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival 2019 an added dimension and an even more vivid flavour.