When the Earl of Kildare - subsequently the Duke of Leinster – commissioned the building of his fine new townhouse in 1745 in what was then the unfashionable south side of Dublin, he can scarcely have imagined that nearly three centuries later, the building and its name would be synonymous with the exercise of democratic government in Ireland, based moreover on the notion – probably totally inconceivable at the time - of universal suffrage writes W M Nixon.

The current role of Leinster House is a classic case of an unintended consequence and one which is largely beneficial. Democracy seems a more natural way of government when its beating heart is in a building which is comfortably located as an integral and elegant yet not-too-grand part of the fabric of the centre of the capital city.

The contemporary configuration and role of Dun Laoghaire Harbour is another interesting unintended consequence. Half a century after Leinster House was built, a maritime movement was getting underway for another major building project – a public one this time - which eventually had several results, the main one being the construction of Dun Laoghaire Harbour in the unchanged overall shape we still know today.

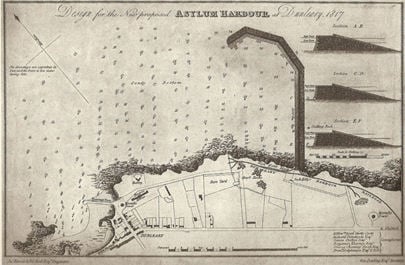

The original suggestion was for one breakwater almost a mile to the east of the little fishing port of Dunleary

The original suggestion was for one breakwater almost a mile to the east of the little fishing port of Dunleary

The idea develops, and the title of “Asylum Harbour” goes public

The idea develops, and the title of “Asylum Harbour” goes public

The increasing loss of life in shipwrecks which resulted from onshore gales in Dublin Bay as vessels tried to enter or leave the shallow port of Dublin led to a growing body of opinion in favour of the construction of a substantial asylum anchorage immediately east of the little creek of Dunleary. The basic requirements were very basic indeed. The initial idea was that there would be just one enormous breakwater pointing approximately northeastward, and then curving northwest at its outer end. The thinking was that in heavy onshore weather, ships could anchor in some safety in its lee until conditions improved.

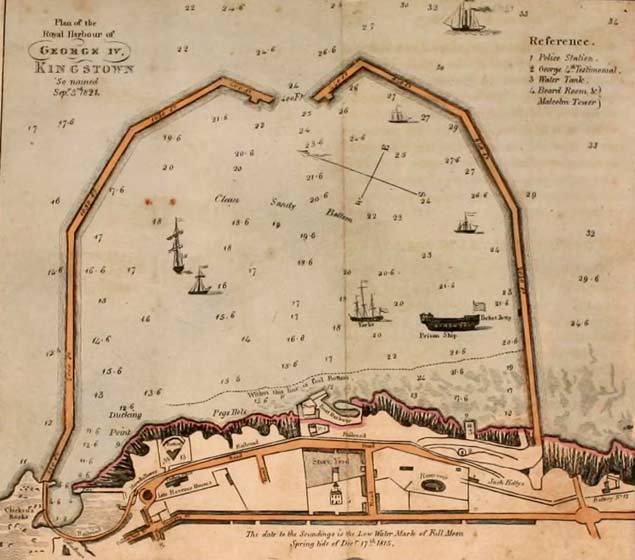

It couldn’t have been simpler, for there was no mention of any shoreside infrastructure to go with it. The idea was that it would only be used by ships in severe conditions and for the shortest possible period. But by the time the construction was underway in 1817, it seemed more sensible to include a West Pier to make it more of an enclosed harbour, and after a Royal visit in 1821, little old Dunleary – still only a fishing village of limited facilities – had become Kingstown, and the massive new port of refuge became known as The Royal Harbour.

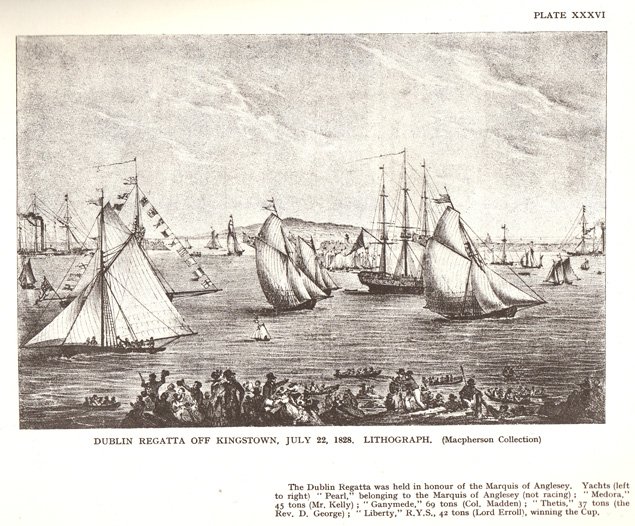

The first regatta at Kingston was staged in 1828

The first regatta at Kingston was staged in 1828

The originators of the project had thought only of providing temporary shelter for merchant and military ships in the most basic possible facility. But other minds and interests saw it in different ways. By 1828 the first regatta had been staged, and at the same time, the first steam and sail-driven ferry boats were running an unofficial occasional cross-channel service from Kingstown to Holyhead and the River Dee.

The authorities were eventually persuaded to include Dunleary within the new harbour, but essentially it meant the end of an ancient coastal community living around its own creek

The authorities were eventually persuaded to include Dunleary within the new harbour, but essentially it meant the end of an ancient coastal community living around its own creek The “Game-Changer” – the opening of the Dublin-Kingstown Railway in 1834 was the real beginning of the harbour town’s progression towards becoming a fashionable residential area and a ferry port.

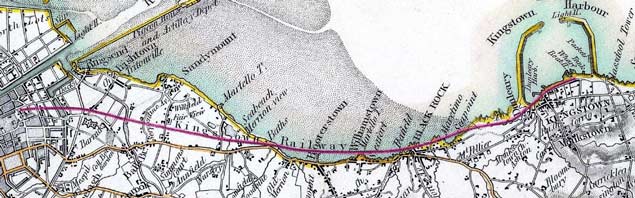

The “Game-Changer” – the opening of the Dublin-Kingstown Railway in 1834 was the real beginning of the harbour town’s progression towards becoming a fashionable residential area and a ferry port.

Then in 1834 the pioneering Dublin to Kingstown railway opened for business. This was the real game-changer in the history of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, which is a long litany of unintended consequences. The railway provided rapid accessibility which led to fashionable if notoriously uncoordinated shoreside residential developments, and the recreational use increased with waterfront yacht clubs. Then as the railway network increased all over Ireland, special boat trains were able to deliver people direct to cross-channel ferries berthed on either side of the new Carlisle Pier.

It was all on a modest scale as the ships were still relatively small, yet by this stage, we were a long way from the original Asylum Harbour concept, as the entrance to Dublin Port had been substantially dredged and steam had taken over as the main motive power for ships.

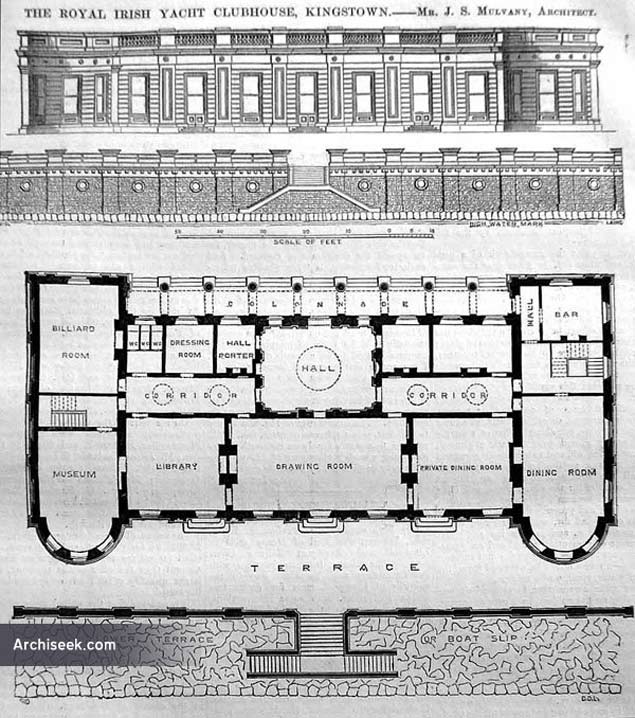

Shoreside recreational facilities developed in tandem with the harbour’s increasing popularity – the plans for the Royal Irish Yacht Club by John Skipton Mulvany. Opened in 1850, it is the world’s oldest complete purpose-designed yacht club building

Shoreside recreational facilities developed in tandem with the harbour’s increasing popularity – the plans for the Royal Irish Yacht Club by John Skipton Mulvany. Opened in 1850, it is the world’s oldest complete purpose-designed yacht club building

The Royal Irish Yacht Club today

The Royal Irish Yacht Club today

There was a sort of golden era when ships of the Royal Navy were still small enough to find Dun Laoghaire a convenient port which was secure from shoreside troubles, such that it is said that a crew change from a naval ship temporarily in Kingstown could be effectively arranged by putting the entire ship’s complement on a closed train which would then travel unhindered across Ireland to the main naval base at Cobh without the public being any the wiser, for these could be restless times.

As long as the main means of access to the ships was by train, Dun Laoghaire worked very well as a ferry port which – thanks to the modest size of the ships – was minimally intrusive both to other harbour users and to those who lived by the harbour.

But the next transport change, trying to deal with Ro-Ro vehicles arriving by road, was much more problematic. For sure, things could be done on the waterfront in the harbour to accommodate Ro-Ro ships without excessive intrusion. But even this apparently simple challenge proved too much during the 1950s – in Dun Laoghaire they built new ramps to accommodate the current generation of vehicle transport ships, but meanwhile Sealink as it then was had commissioned a new larger ship, and somehow omitted to tell them in Dun Laoghaire that this vessel would need a different sort of ramp…..

It was sorted out in a bodged-together sort of way, and as long as the cargo was mostly cars and vans, it was manageable ashore. But Kingstown/Dun Laoghaire’s ad hoc township development in the 19th Century meant that away from the waterfront, it was a maze of narrow roads and streets, and harbour access with the new super-trucks was a real headache.

So although a new Ferry Terminal for the HSS (High Speed Service) was built in the 1990s, to function smoothly it really would have required direct access of semi-motorway quality to the new M50.

The currently unused Ferry Terminal (right foreground) includes an extensive area originally intended for waiting vehicles. Photo Courtesy Barrow Coakley/Simon Coate

The currently unused Ferry Terminal (right foreground) includes an extensive area originally intended for waiting vehicles. Photo Courtesy Barrow Coakley/Simon Coate

There are many other reasons why the HSS and indeed all ferry services out of Dun Laoghaire ended in 2015. But the unintended consequence is that for nearly five years now, Dun Laoghaire Harbour has been primarily a recreational and residential amenity, which is a long way indeed from that suggestion around 1800 that just one sheltering breakwater should be built. And the ultimate irony is that the lone breakwater in question is now the East Pier which most Dubliners see as being perfect for a stroll, brisk walk or jog – in fact, some reckon that’s what it was designed for.

The suggestion that the Harbour might be quite drastically modified in order to accommodate cruise liners was fiercely resisted, and with the news that even the citizens of Cobh are complaining about the vulgar 24-hour noisiness of the modern cruise liners which berth at their town, we can only imagine the raised levels of indignation in Dun Laoghaire were such a thing to happen in a township where the waterfront is now very much the trendy place to live.

Thus a major sailing event like the Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta is important in many ways, and particularly for showing the harbour’s potential as a magic place to have your home. But how can this vitality be given a year-round span? Organisations like the Irish National Sailing School do heroic work in giving the harbour area some vitality on a year round basis, yet as any aerial photos show, the piecemeal development of the waterfront over the years as various uses have arisen, functioned and then died, has left behind much empty space which can surely be better utilised.

A challenge with Dun Laoghaire is creating a natural interaction between harbour and town, as they are artificially divided by the intervening waterfront roads and railway. Two possibilities are new communities created around the Coal Harbour (left) and on the parking area of the Ferry Terminal. Photo courtesy Barrow Coakley/Simon Coate

A challenge with Dun Laoghaire is creating a natural interaction between harbour and town, as they are artificially divided by the intervening waterfront roads and railway. Two possibilities are new communities created around the Coal Harbour (left) and on the parking area of the Ferry Terminal. Photo courtesy Barrow Coakley/Simon Coate

The basic problem with Dun Laoghaire Harbour is that there is no “Vieux Port”, no ancient corner where you can still find ample waterside evidence of the harbour as it was in its earliest days with ancient inns and boatworks and whatnot. Such places must have existed in old Dunleary, but the roads and the railway have cut them off from the harbour, and they have long since disappeared underneath new developments.

So maybe after we’ve recovered from Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta 2019, we might get some fresh thinking on how to keep the harbour quietly yet genuinely alive all year round. For instance, surely an imaginative town planner/architect could think of ways of giving the area around the Coal Harbour more of a sense of community?

The inner harbour (still known as the Coal Harbour) is all that remains of the ancient coastal community of Dunleary. With some radical thinking, it might be possible to create a proper little maritime community around it

The inner harbour (still known as the Coal Harbour) is all that remains of the ancient coastal community of Dunleary. With some radical thinking, it might be possible to create a proper little maritime community around it

Equally, that vast empty area which used to be the waiting area for the HSS Ferry – even with some space taken up by the Ferry terminal building - is still so large that it is going to take a real leap of vision to find some genuinely valid use for it.

The problem is that Dun Laoghaire is such a rare case. There are very few other comparable ports and seaside towns from which it can learn the way forward. And as it is, many people are perfectly happy with the harbour as it is. But surely it could give a better sense of itself, a real feeling of identity?

That said, the way it is today is largely as a result of unintended consequences, with people who like it as it is fighting their corner with utter determination. So maybe it would be flying in the face of experience to try to plan anything which might have longterm and worthwhile intended consequences. Maybe if everyone just continues to KBO, it’ll be all right in the end, thanks to continuing the long tradition of beneficial unintended consequences.