In 1828, when the recently re-named and still only semi-finished harbour of Kingstown on Dublin Bay staged its first regatta, it certainly gave an indication of the transformed place’s potential for waterborne sport. Yet it was not until 1831 that the first club – the Royal Irish YC in its earliest form – came into being. But on the south coast at Cork, the stately Water Club had been going about its manoeuvres since 1720, and was organising racing by 1765 and probably earlier while going on to become the Royal Cork YC in 1831. And on the west coast in Kerry and along the Shannon Estuary, recreational sailing was relatively well established – not least because it provided a useful cover for some profitable smuggling of low-volume high-value commodities from France, Spain and Portugal.

Be that as it may, by the 1820s regattas were being staged at what was then one of the main ports, the sheltered though tidal Shannonside creek at Kilrush on the south coast of Clare, and in 1828 Maurice “Hunting Cap” O’Connell – the uncle and effectively guardian in his youth of Daniel O’Connell of Derrynane, The Liberator - organised a Kilrush regatta which led to the formation of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland.

The club thrived, and by 1838 it was the named club of at least two dozen yachts, some of them quite substantial, with 18 of them based in Kilrush while others were kept by their owners on moorings in the estuary beside their often quite stately homes, a classic case being the Knight of Glin with his 30-ton cutter Rinevella moored off Glin Castle on the south shore.

The Shannon Estuary – 55 nautical miles of history-filled waterway

The Shannon Estuary – 55 nautical miles of history-filled waterway

Thus the sailing scene on the Atlantic seaboard was thriving while the Dublin Bay programme was still in its infancy. But the situation was totally and tragically changed with the Great Famine of 1845-47. Apart from the human scale of the disaster - which we still do not fully grasp, and probably never will – while it may be simplistic to say that the economy of Western Ireland was destroyed, basically that’s what happened. Despite this, much of life along the east coast went on as normal, and yachting in Kingstown underwent a phase of rapid development.

Retreating from the wasteland which the West had become, what was left of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland became an itinerant organisation, based for a while in Dublin city and then in Dun Laoghaire and finally in Cork Harbour, where it was supposedly wound up in Cobh in 1870. But it so happened that back in Kilrush the Glynn family had retained some artefacts, documents and records of the old club, other memorabilia was gradually traced and brought home over the years, for there were those who felt that the old Royal Western YC of Ireland had never really died, it was only sleeping, and all it needed was some miraculous revival of the port of Kilrush to waken it up.

Kilrush did slowly revive as a port after the famine, but it was for the utilitarian purposes of handling cargo in the dock, while a pier nearby at Cappagh served the needs of the Shannon ferry steamers which were such a feature of the estuary before rail and then road took over. After that, the port became a ghost of its former self, but there were those who could see its potential.

And the miracle came in 1990, when Brendan Travers of Shannon Development spearheaded the project to provide a barrier with a sea lock to make Kilrush into a proper marina. Today, it has facilities which put the allegedly pace-setting East Coast ports to shame, with the marina run by Simon McGibney while master-shipwright Steve Morris (who’s from New Zealand, but Irish women like his wife Michelle have a way of ensnaring useful talent and keeping it here) has been with the boatyard with its commodious sheds and workshops since 2001, where they seem capable of all forms of boat-work in any material, and to world class standards too.

Kilrush today, with the extensive boatyard (centre) providing facilities that most other Irish sailing harbours can only dream of

Kilrush today, with the extensive boatyard (centre) providing facilities that most other Irish sailing harbours can only dream of

With this setup developing, the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland re-emerged as the club at Kilrush with a healthy marina-based fleet. In the early summer of 2007, a bundle of energy from Limerick called Ger O’Rourke contacted the Royal Ocean Racing Club to enter his Cookson 50 Chieftain for the up-coming Rolex Fastnet race in August. He was told he’d be 46th on the waiting list, but not to worry - many early entries tended to drop out, and with bad weather forecast, he was in with a good chance of a place.

O’Rourke had just completed a Transatlantic race from Newport to Hamburg to take second place, but he had this weird superstition of never entering his boat for the next big race until the previous one had been completed. Once again it came good - on the Tuesday before the Fastnet was due to start on the Saturday, the RORC told him it was all systems go, the place was there, so he rushed his crew together, they sailed a magnificent heavy weather race, and Chieftain became the overall winner of the 2007 Rolex Fastnet Race, making the Royal Western of Ireland and Kilrush the only Irish club and port which can claim this rare distinction.

Ger O’Rourke’s Cookson 50 Chieftain from Kilrush shortly after the start of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007, which she won overall – the first and still the only Irish boat to do so. Photo: Rolex

Ger O’Rourke’s Cookson 50 Chieftain from Kilrush shortly after the start of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007, which she won overall – the first and still the only Irish boat to do so. Photo: Rolex

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that when the most varied group of people in Irish sailing that you’ve ever seen converged on Kilrush in Tuesday’s incredibly bright and uninterrupted sunshine for the launching of the first of the re-born Dublin Bay 21s which are being brought back to life for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra by Steve Morris and the equally talented Dan Mill and their team (which includes Kilrush’s own James Madigan of Ilen fame), we weren’t making a patronizing visit to encourage a new place on its way.

The Naneen Restoration Team included (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barrra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

The Naneen Restoration Team included (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barrra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

On the contrary, it was more like a pilgrimage to a special place that was outdone in historic sailing style only by Cork Harbour, for in Dublin Bay organised sailing was just getting going when Kilrush was thriving, and Belfast Lough was likewise barely started. But back in the 1820s when life lacked many of today’s mostly superfluous distractions, sailing was big in the west – think Sligo too - and Kilrush and the Shannon Estuary were in the forefront of its energetic development, typified by the Knight of Glin who took his cutter Rinevella to Galway in 1834 for a big regatta, and won western sailing’s equivalent of the Galway Plate.

However, from 1850 onwards there’s no doubting Dublin Bay was a global pace-setter in sailing development, and the establishment of Dublin Bay Sailing Club in 1884 provided an organisation which very quickly was co-ordinating all the sailing of the three major Kingstown yacht clubs, establishing new classes of increasing boat sizes such that by 1898 it was the DBSC’s imprimatur which brought the famous Fife-designed Dublin Bay 25ft ODs into being.

All these numbers refer to the waterline length, which means the 25s were generously-canvassed 37-footers, the jet-set of Dublin Bay One-Design racing. So much so, in fact, that very soon there was a growing movement for something similar in style but in a smaller and more economically-manageable size. William Fife was busy with America’s Cup yachts for Thomas Lipton and other large projects for super-rich clients, so they turned to Scotland’s new rising star in the yacht design firmament, Alfred Mylne, who had already created a useful 20ft waterline design for Belfast Lough sailors, the Star class, which set a simple gunter sloop rig.

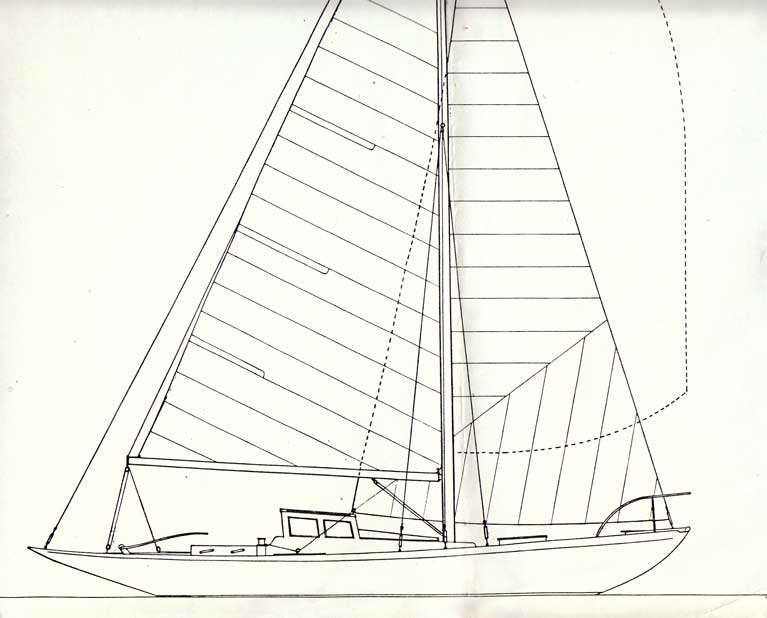

Simplicity was not the keynote in the original rig of the new Dublin Bay 21s in 1903 – in fact, for the first 60 years of their existence, they were defined by this challenging jackyard topsail-setting gaff cutter rig.

Simplicity was not the keynote in the original rig of the new Dublin Bay 21s in 1903 – in fact, for the first 60 years of their existence, they were defined by this challenging jackyard topsail-setting gaff cutter rig.

But simplicity was not the keynote for the new Dublin Bay 21. Slightly larger, she had a longer and more elegant stem than the Star’s rather snubbed bow, and instead of a straightforward hyper-economical gunter mainsail with just one headsail, she set acres of gaff rig with a jackyard topsail and was cutter-rigged with it – four sails by comparison with the Star’s two, and that’s before you add the spinnaker.

The first three boats were building with Hollwey of Ringsend in the winter of 1902-03, as the established Kingstown builders James Clancy and J E Doyle were busy with other works, notably yet more DB 25s. The bigger class had received a shot in the arm with a new boat ordered for the 1903 season for the Viceroy, Lord Dudley, to be built by Doyle. This meant that when the first five DB 21s raced in 1903 (two more having been built by James Kelly of Portrush), their advent was somewhat overshadowed by all the razzmatazz attached to the Viceroy racing in his new DB25 Fodhla.

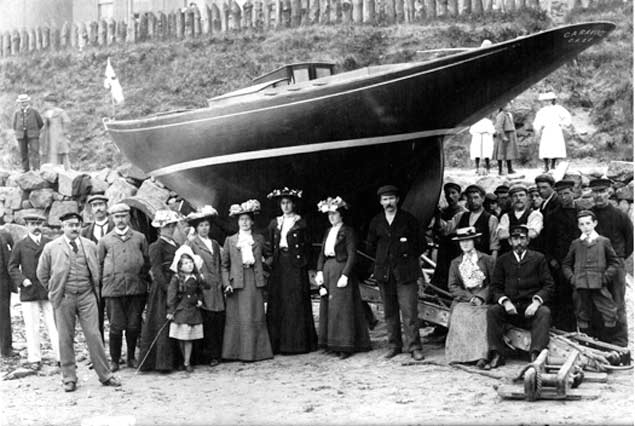

Garavogue on her launching day at Portrush in 1903

Garavogue on her launching day at Portrush in 1903 Garavogue in action in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her replacement hull has been built by The Elephant Boatyard in England, and is now in Kilrush for completion

Garavogue in action in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her replacement hull has been built by The Elephant Boatyard in England, and is now in Kilrush for completion

But the smaller class’s quality was soon recognized, and by 1908 they’d achieved their optimum number of The Sacred Seven with Geraldine being built by Hollwey, while Naneen – no 6 – had emerged as the only Kingstown-built boat. She was the work of James Clancy in 1905, built for a serial racing yacht owner called T Cosby Burrowes from Cavan. He must have owned a substantial part of that most rural of Irish counties, for it was presumably rental income which enabled him to be a member of eleven yacht clubs in Ireland, Scotland and England while buying new boats on a fairly regular basis. But though he raced in many places, Dublin Bay was his spiritual sailing home, and he’d served as DBSC Vice Commodore in 1900-1901.

The Ireland of people like Cosby Burrowes was to change inexorably through the 20th Century, yet the Dublin Bay 21s steadily continued to give great sport with such consistency that, despite being just seven in number, the regularity of their turnouts and the spectacular nature of their appearance became the best-known feature of Dublin Bay sailing.

But by the early 1960s the advent of series-production built fibreglass boats with alloy masts and synthetic sails was making their continued existence problematic, and in 1963 they persuaded veteran designer John Kearney (he was 83 at the time) to provide them with a new masthead Bermudan rig of 400 square feet as opposed to the original gaff’s 600, and they also requested a new coachroof with a doghouse to provide standing headroom.

The new masthead Bermudan rig as fitted in 1963 enabled exceptional loading to be applied by the standing backstay, while the unsightly new doghouse distracted attention from the elegance of the sheerline.

The new masthead Bermudan rig as fitted in 1963 enabled exceptional loading to be applied by the standing backstay, while the unsightly new doghouse distracted attention from the elegance of the sheerline.

John Kearney was up to his tonsils at the time designing and over-seeing the building of the 54ft yawl Helen of Howth for Perry Greer, but his age of 83 notwithstanding, he took on this extra task and the simple rig he created balanced very well. It gave good performance while needing a smaller crew, but veterans of that Dublin Bay 21 era who were in Kilrush on Tuesday were mixed in their approval.

Paddy Boyd raced on his father’s Oola as a schoolkid, and he could well remember the magic moment when the vital but inadequate bilge pump – his special job - was replaced by a luxurious new Whale Gusher 25. Anyway, he is in no doubt that the new rig gave the class a further 22 years of useful life. But Fionan de Barra, the Keeper of the Flame who has kept The Sacred Seven intact as a group ever since they stopped sailing, and his project partner Hal Sisk, are of the opinion that the new masthead rig with its standing backstay – often tensioned with a wheel - meant that the mast was being pushed down into the hull in a destructive way that hadn’t been possible with the original gaff rig with its running backstays.

DB21 veteran Paddy Boyd with Naneen in Kilrush. Racing regularly as a schoolboy aboard the family’s Oola, his happiest memory is of the day his father finally acquired a bilge pump which was man enough for the job. Photo: W M Nixon

DB21 veteran Paddy Boyd with Naneen in Kilrush. Racing regularly as a schoolboy aboard the family’s Oola, his happiest memory is of the day his father finally acquired a bilge pump which was man enough for the job. Photo: W M Nixon

Either way, the class was getting very tired by the mid-1980s. But any considered decision as to their future was decided by Hurricane Charlie in August 1986, with northeast gales of unbelievable ferocity sweeping into Dun Laoghaire to leave the Dublin Bay 21s either sunk or seriously damaged.

That was 1986. It is now 2019. But the sheer style of the DB 21s has never been forgotten. And as for what was left of the boats themselves, Fionan de Barra and friends managed to keep them intact as a group in various locations in County Wicklow, while one proposal after another was put forward for their revival.

Naneen, the only DB21 to have actually been built in Dun Laoghaire, looking very sad in a Wicklow farmyard some years after the class had stopped sailing in 1986. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Naneen, the only DB21 to have actually been built in Dun Laoghaire, looking very sad in a Wicklow farmyard some years after the class had stopped sailing in 1986. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Naturally the yachting historian and classic yacht activist Hal Sisk was interested, but he had other projects in hand such as the restoration of the 1894 G L Watson 37ft cutter Peggy Bawn, a meticulous project finished in 2003 which has seen Peggy Bawn winning regattas and awards on both sides of the Atlantic.

But gradually he and Fionan started putting ideas together, and in a world which changes more rapidly than ever, they reckoned that a way of restoring the DB 21s as a class is to think of new ways of ownership and use. To do this they would have to use a rig simpler than the labour-intensive time-consuming jackyard tops’l setup of the originals, and a straightforward gunter sloop set up such as Alfred Mylne designed for a Scottish-built boat to the hull design – Zanettta in 1918 - seemed to fit the bill.

The easily-handled rig designed by Alfred Mylne for the Scottish-owned Zanetta of 1918 is the basic inspiration for the new rig on the class in Dublin Bay

The easily-handled rig designed by Alfred Mylne for the Scottish-owned Zanetta of 1918 is the basic inspiration for the new rig on the class in Dublin Bay

A traditional and historic local class such as the Howth 17s is one in which the people involved and their sense of community through the boat are every bit as important as the new boat itself, and thus the numbers of interested people are maintained over the years. But where a class has been sitting together but derelict and moth-balled for thirty years with the original owners and crews dying off and all ownership rights gradually accruing to one person – in this case Fionan de Barra – much radical thinking is needed.

Howth Seventeens in action in their time-honoured style. They have been functioning continuously as a racing class since 1898, and with 19 boats, have an established total crewing panel of around a hundred people for whom a Seventeen is the first choice if they wish to go sailing. But as the new-look Dublin Bay 21s will be starting from scratch with no basic crewing panel, a completely new approach to ownership and the running of the boats is being devised. Photo Stormyphotos/Tom Ryan

Howth Seventeens in action in their time-honoured style. They have been functioning continuously as a racing class since 1898, and with 19 boats, have an established total crewing panel of around a hundred people for whom a Seventeen is the first choice if they wish to go sailing. But as the new-look Dublin Bay 21s will be starting from scratch with no basic crewing panel, a completely new approach to ownership and the running of the boats is being devised. Photo Stormyphotos/Tom Ryan

Thus Hal and Fionan have come up with the idea that the restored Dublin Bay 21 class – with the hulls built-in modern wood-style using the WEST system – would be an association-owned class of boats in a Dun Laoghaire Harbour which is itself being re-imagined for its use as an amenity and recreational area. To this new-use classic harbour they would bring a group of classic boats which are maintained as a unit, and accessible to all for sailing and special racing events based on the harbour of which they were such a natural part for 83 years.

The “new” Naneen at an early stage of her re-build. Photo: Steve Morris

The “new” Naneen at an early stage of her re-build. Photo: Steve Morris

It’s an ambitious idea, but in this age of disappearing private ownership and shared use of vehicles ashore, with new business names like Borrow-a-Boat coming to the fore, it could well be that this re-born 116-year-old class is in the vanguard of how we will sail in the future.

Meanwhile, the boats have had to be re-built, and in Ireland they started with the only Dun Laoghaire-built boat, the Naneen of 1905 built by James Clancy, and took her to Steve Morris in Kilrush, while the Garavogue – built by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903 – went to classic boat specialists The Elephant Boatyard in the south of England.

Even with such skill involved in both England and Ireland, it has been a demanding task, but fortunately beforehand they could draw on the knowledge of design historian and classic specialist Theo Rye, and then after his sad and untimely death in 2016, the many talents of Paul Spooner took on the advisory role, and gradually the developing project began to take shape.

The casually interested might think it is all taking a remarkably long time, but so many novel concepts and new ways of thinking about boat use are evolving as each stage is passed that when the “new” DB21 class is complete, we’ll find that Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra are true pioneers of sailing.

A meeting of minds. Ilen skipper Paddy Barry (right) with Frank Larkin (left) and Steve Morris as the about-to-be-launched Naneen flies the DBSC burgee. Photo: W M Nixon

A meeting of minds. Ilen skipper Paddy Barry (right) with Frank Larkin (left) and Steve Morris as the about-to-be-launched Naneen flies the DBSC burgee. Photo: W M Nixon

Certainly the very supportive crowd which turned up in the Kilrush sunshine on Tuesday to wish them and the build team of Steve Morris and Dan Mill was representative of a very wide swathe of people seriously interested in classic boats and what you can do with them, such as Paddy Barry and Jarlath Cunnane fresh back from the restored Ilen’s voyage to Greenland, and James Madigan who was not only closely involved in re-building the Ilen in Limerick and Oldcourt and sailing to Greenland, but is from Kilrush and is now back home working with Steve and Dan on completing the Garavogue, whose hull has arrived in Kilrush from England.

There were several there who had sailed on the DB21s in the old days, in fact your columnist sailed in the Geraldine when she was still gaff-rigged in the ownership of Paul Johnson. But much more interesting were the views of Paddy Boyd, who has distant childhood memories of the old rig, and happy recollections of youthful exuberance under the new one.

In gazing at Naneen as she glowed in the sunshine with a sense of weightlessness in the boat hoist, he was moved to comment on how elegant the sheerline now looked under the original coachroof. John Kearney himself preferred neat low coachroofs - he thought doghouses were the invention of the devil - but the DB 21 owners of 1963 demanded it, and the result was a boxy shape which somehow disguised the fact that the original sheerline was well nigh perfect.

Certainly it was well-appreciated by Ian Malcolm of Howth, who was there on behalf of the Howth 17s but with a special interest, for after Storm Emma wreaked havoc on the Howth Seventeen fleet in their pier-end storage shed in March 2018, it was boat no 6, Anita built by James Clancy in 1900, which was the only total loss. Thus it fell to Ian, with his French connections, to arrange her re-build by Paul Roberts’ Les Atelier d’Enfer organisation in Douarnenez under the French government’s subsidized boat-building schools programme.

People who re-build James Clancy boats with James Clancy people are left to right) Ian Malcolm who arranged the French re-build of Howth 17 No 6 Anita, built by James Clancy in 1900, with Ann Clancy Griffin, James Clancy’s grand-daughter who lives in Kilrush, James Clancy’s great-grand-daughter Sinead Griffin (also of Kilrush), and Hal Sisk, who has been central to the re-build of Naneen, DB 21 No 6, built by James Clancy in 1905. Photo: W M Nixon

People who re-build James Clancy boats with James Clancy people are left to right) Ian Malcolm who arranged the French re-build of Howth 17 No 6 Anita, built by James Clancy in 1900, with Ann Clancy Griffin, James Clancy’s grand-daughter who lives in Kilrush, James Clancy’s great-grand-daughter Sinead Griffin (also of Kilrush), and Hal Sisk, who has been central to the re-build of Naneen, DB 21 No 6, built by James Clancy in 1905. Photo: W M Nixon

This meant that in Kilrush on Tuesday we’d two sets of people who have been closely involved in the re-building of a Clancy of Dun Laoghaire boat during the past two years, but the coincidences didn’t stop there, as James Clancy married a Kilrush woman, and the family now has many connection in the town, with his grand-daughter Ann Clancy Griffin with her daughter Sinead Griffin doing the launching honours after Father Anthony Keane – who was Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey before he went up to Greenland on Ilen – had made a quietly elegant ceremony out of blessing the boat.

When he sailed to Greenland in the Ilen in July, he was Brother Anthony of Glenstal Abbey, but now he is Father Anthony Keane, and in his new capacity, he blessed Naneen before her launching on Tuesday. Photo: W M Nixon

When he sailed to Greenland in the Ilen in July, he was Brother Anthony of Glenstal Abbey, but now he is Father Anthony Keane, and in his new capacity, he blessed Naneen before her launching on Tuesday. Photo: W M Nixon

And then Naneen was launched. Simply by watching her being lowered gently we were given ample opportunity to admire the way in which Alfred Myne has harmonised the lines, such that every sweet curve complements all the other, with the little cabin, in particular, being a masterpiece. On the original drawings Mylne light-heartedly named its interior as “The Den”, but the 21s proved such good seaboats that one of the original owners, Herbert Wright who later went on to be founding Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club in 1929, took his new DB21 Estelle to Scotland on a cruise which worked out so well he wrote it up for Yachting Monthly magazine, which prompted Hal Sisk to claim that the Dublin Bay 21s were thus the world’s first genuine cruiser-racer class.

The harmony of Naneen’s pure lines as drawn by Alfred Mylne became even more evident as she was lowered gently into Kilrush Creek. Photo: W M Nixon

The harmony of Naneen’s pure lines as drawn by Alfred Mylne became even more evident as she was lowered gently into Kilrush Creek. Photo: W M Nixon

Is she not very lovely? That Alfred Mylne, he certainly had an eye for a boat….. Photo: W M Nixon

Is she not very lovely? That Alfred Mylne, he certainly had an eye for a boat….. Photo: W M Nixon

Clearly there’s a quality to their size and the way they feel when you step aboard which seems just right, and suggests uses more ambitious than simply racing in Dublin Bay, though heaven knows the pace of their racing was scarcely simple, for it was hectic and furiously – sometimes genuinely furiously – competitive.

But all would be well at the end of the day, and with the new creation afloat, Fionan ushered us back to the boat-building shed for the perfect boat-launching lunch, a simple yet effective and nourishing boat-oriented meal provided by Noel Ryan of Ryan’s Butchers & Deli in the town. It was an extension of the opportunity to meet the huge diversity of people who had come to wish this extraordinary project well, a glimpse of the area’s diversity for there was time to talk with Frank Larkin of Limerick, whom I first met through sailing. Then when he became Corporate Communications Manager for Shannon Development, he used to recruit me to give slide shows to Limerick’s sailing fraternity, and the next day we’d go to Foynes or Kilrush to see the developing local setup, all extremely educational for this was in the days before Kilrush had its barrier and Foynes had yet to have its largely voluntarily-installed marina.

The perfect post-launch boatyard lunch gets underway beside a new traditional gleoiteog which is another high-standard project the yard has underway at the moment. Photo: W M Nixon

The perfect post-launch boatyard lunch gets underway beside a new traditional gleoiteog which is another high-standard project the yard has underway at the moment. Photo: W M Nixon

There too was Kim Roberts who has run a boatyard in her time, and then driven an enormous crane for big contracts on the south shore, and has since been manager of Kilrush marina but is now running Vandeleur antiques from The Old Forge in Killimer and sailing a restored classic timber Drascombe which, as we saw last week, she has taken about as far up the Shannon as it is possible to get from Kilrush.

From up the Shannon was David Beattie of Lough Ree, whose steel version of Slocum’s Spray may have originated in the Lough Ree area, but now under David’s command she has cruised extensively in the Med before returning recently to Ireland for work to be done at the Ryan & Roberts boatyard at Askeaton on the Shannon Estuary’s south shore. And equally appreciative of the Naneen restoration was that legendary shipwright sailor Albert Foley, who’s on the mend after a recent illness, and plans to get his Swan 36 – which he re-built after everyone else considered her a write-off after she’d been run down by a survey vessel – back sailing again.

Then came the moment of truth - the post-lunch revisit to the floating Naneen to see how things were. The sheer pleasure of being aboard a pristine wooden boat in the sunshine with new varnishwork and a slight hint of linseed oil and all the aromas of a healthy environment in The Den were followed by that important ceremony: The First Lifting of the Floorboards.

Super workmanship in evidence below on Naneen, looking forward from “The Den”. Photo: W M Nixon

Super workmanship in evidence below on Naneen, looking forward from “The Den”. Photo: W M Nixon

They’ll have a problem with Naneen. No arachnophobes will be able to sail aboard. The bilges fore and aft were bone dry. Inevitably some dust and other peculiar forms of nutrition and the occasional tiny insect will find their way in, and in time there will be a spider’s web or two. Definitely not a boat for arachnophobes……

Exquisite workmanship hiding structural strength – the hanging knee fitted in Naneen to distribute the load from the internally-installed main shroud chainplate. Photo: W M Nixon

Exquisite workmanship hiding structural strength – the hanging knee fitted in Naneen to distribute the load from the internally-installed main shroud chainplate. Photo: W M Nixon

Before leaving Kilrush for the long haul home courtesy of Ian Malcolm with his high-and-very-mighty boat-towing vehicle, we had one further pleasant task – to pay our respects to Sally O’Keeffe in the marina. She is the handsome workmanlike 25ft cutter designed by the talented Myles Stapleton to a concept based on the Shannon Estuary hookers of all sizes which used to carry cargoes the length and breadth of the mighty waterway, and there was one in particular called Sally O’Keeffe which was based in Querrin to the west of Kilrush, where she’s part of folk memory.

A sort of Men’s Shed group in Querrin got together to build an interpretation of the Sally in the big barn at a local farm, Steve Morris came along and kept the work on track, and the result is one of the most attractive boats in all Ireland, a no-nonsense multi-purpose craft which has turned heads and won competitions at places as far apart as Glandore, the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival in West Cork, and Cruinniu na mBad in Kinvara on Galway Bay, making a point of sailing to these places along the Atlantic seaboard from Kilrush.

Sally O’Keeffe is the outcome of a very successful community venture in neighbourhood boat-building guided by Steve Morris.

Sally O’Keeffe is the outcome of a very successful community venture in neighbourhood boat-building guided by Steve Morris. Steve Morris – he seems to be able to turn his hand to any boat-building project with complete success. Photo: W M Nixon

Steve Morris – he seems to be able to turn his hand to any boat-building project with complete success. Photo: W M Nixon

She’s about as perfect as you can get in her way, yet she’s as different as possible from the equally perfect Naneen, and we’d the chance to compare them directly, for even as we were admiring Sally, the Naneen came into the berth just across the walkway.

All I can say is that when some project gets the Steve Morris touch, it becomes something very special indeed. We departed on a high, determined to make the best of that extraordinary day by enveloping the entire Shannon Estuary experience through heading homewards by way of the Killimer-Tarbert Ferry, and along the south shore we were able to look across to the islands at the mouth of the estuary of the Fergus River where the 1886 America’s Cup Challenger Galatea came to visit Paradise House (that’s really what it was called), the Shannonside ancestral home of owner William Henn.

Then we swept into Foynes to admire the crisp style of the thriving yacht club while gazing thoughtfully across to the cottage on Foynes Island where global circumnavigation pioneer Conor O’Brien of Saoirse fame spent his last years, and where the restored Ilen had come in the Autumn of last year to pay her respects, and then we went to see Cyril Ryan and the wide range of work he does at Ryan & Roberts at Askeaton, where he has a boatyard in classic style where we marvelled at the huge road crane Kim Roberts used to drive, and marvelled equally at the enormous tidal range in the River Deel, for David Beattie’s Ree Spray was a very long way down indeed in a muddy pool at the pontoon.

Product line…..the “new” Naneen (beyond) and Sally O’Keeffe (foreground) get together in Kilrush Marina at the end of an extraordinary day. Photo: W M Nixon

Product line…..the “new” Naneen (beyond) and Sally O’Keeffe (foreground) get together in Kilrush Marina at the end of an extraordinary day. Photo: W M Nixon

And finally, we went for a pit stop in the Dunraven Arms in Adare and wondered again at the sometimes misunderstood genius of the neighbourhood’s Lord Dunraven, with his two America’s Cup Challenges in 1893 and 1895. Then with a seemingly eternal sunset at our backs, we left Ireland and went back across the isthmus to Howth, simply stunned by the memory of the incredible range of the Shannon Estuary’s sailing history and its many links, a memory which had somehow given us a much clearer understanding of what it is that Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra are trying to achieve with their pioneering vision for the future of the DB21 class.

Naneen is coming home….Naneen, the only Dublin Bay 21 to be actually built in Dun Laoghaire, is the first one to be restored. She is seen here in the successful ownership of Terry Roche during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Olga Scully

Naneen is coming home….Naneen, the only Dublin Bay 21 to be actually built in Dun Laoghaire, is the first one to be restored. She is seen here in the successful ownership of Terry Roche during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Olga Scully