In Ireland, these days, the name of Rod Stephens is most readily associated with an international award - the Cruising Club of America’s Rod Stephens Trophy for Outstanding Seamanship - for the very good reason that during the past six years, it has twice been awarded to Irish skippers: Sean McCarter in 2014, and Gregor McGuckin in 2018.

We were shooting the breeze the other day with Gregor about how his dismasted Golden Globe entrant, the Biscay 36 ketch Hanley Energy, continues doggedly afloat in the Indian Ocean with the possibility of retrieval always a consideration. It was another opportunity to congratulate him again on his award last year of the Trophy for his heroic efforts to rescue the seriously injured Indian competitor Abilash Tomy, despite his own injuries and his boat’s crippled jury-rig condition. It was then that the memory suddenly arose that once upon a time, Rod Stephens himself came to Howth to give a practical demonstration and talk about getting the best from an offshore racer’s rig.

In fact, it was exactly fifty years ago to the day from this coming Monday, May 11th 1970, and it’s all in the June 1970 issue of Afloat Magazine on quaint old-fashioned paper. But we’ll return to that in due course, for in those days everyone knew who Rod Stephens was, but fifty years down the line a spot of background info mightn’t go amiss.

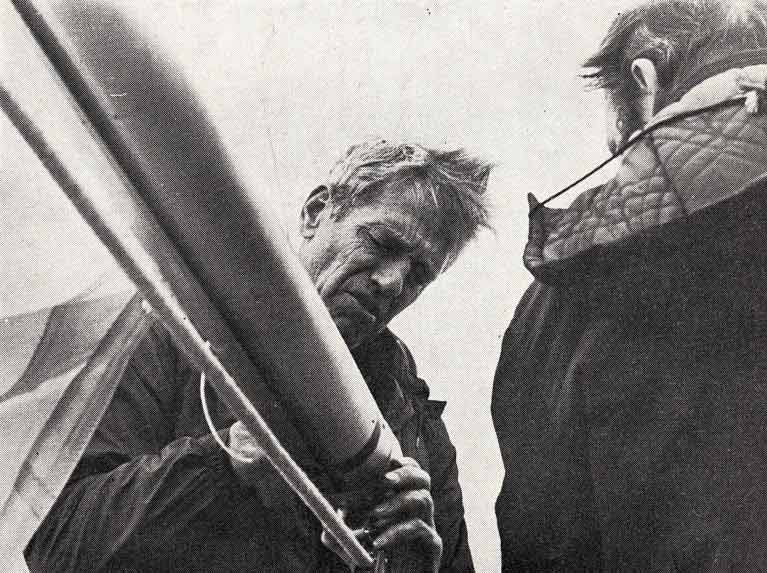

Rod Stephens in Howth aboard Jack McKeown’s S&S 34 Korar, May 11th 1970. Photo: John Bourke

Rod Stephens in Howth aboard Jack McKeown’s S&S 34 Korar, May 11th 1970. Photo: John Bourke

Although Rod Stephens died in 1995 aged 85, it took a couple of years, and more before 21 of his former shipmates and other friends felt they’d a sufficiently worthy concept for the CCA with this universal trophy in his honour. But it’s a measure of the respect in which his memory is held that the Rod Stephens Trophy is now the global benchmark, the world’s gold standard, for particularly heroic and efficient acts of seamanship and rescue in extreme conditions.

The scope of the award is so broad that it took a few years to get its parameters defined, with an international network in place to identify true winners after the first award in 2000. But by 2007 one of its objectives were signalled loud and clear when Mike Golding received the trophy for his textbook rescue of Alex Thomson in the Southern Ocean when the latter’s Hugo Boss was sinking in a round the world race. An extreme situation in extreme conditions, with a boat not remotely designed for performing rescues, and with the correct decisions being made when there may be only one chance to get it right – that became one of the hallmarks of the Rod Stephens Award.

There’s more to it than outstanding rescues, however, as the 2013 award was to Jean-Pierre Dick for his extraordinary skill in completing the last 2,650 miles of the 2012-2013 Vendee Globe with most of his keel missing. But it’s in the area of dramatic rescues that the Rod Stephens Award tends to get the most attention, although the standards are so strict that some years there’s no award at all.

Ireland came into its spotlight for the first time in 2014 when Sean McCarter of Lough Swilly YC was in command of the Clipper Ventures round the world racer Derry/Londonderry/Doire, and they were in the final roughest stages of the China to San Francisco leg when crewman Andrew Taylor went overboard in the worst possible conditions of poor visibility, extremely strong winds, mountainous and confused seas, and hypothermia-inducing water temperature.

Yet they located the casualty and got him aboard again, albeit in a state of potential shock. But that too was dealt with by Sean McCarter in the best possible way in a brilliant mood-lightening move. He came along the deck and quipped to his retrieved shipmate: “Hi Andy, we’re going to San Francisco. Like to come along?”

Sean McCarter receives the Rod Stephens Trophy from CCA Commodore Tad Lhamon in the Model Room of the New York Yacht Club, March 2015

Sean McCarter receives the Rod Stephens Trophy from CCA Commodore Tad Lhamon in the Model Room of the New York Yacht Club, March 2015

The following Spring, Sean was in the famous Model Room of the New York Yacht Club to receive the award from CCA Commodore Tad Lhamon, and the spirit of Rod Stephens was there. And it was vividly there again last year when Gregor McGuckin received the Rod Stephens Trophy in the same august surroundings from Commodore Bob Medland, and in his brief words of acceptance - for you could hardly call it a speech yet he said everything with eloquence – Gregor evoked the Stephens spirit by commenting on the Golden Globe’s “unwritten understanding that when one of us gets into difficulty, we know there is a whole group of people who will have our back out there”, and concluded by saying: “I just happened to be in this situation, and have no doubt that anyone else in my situation would have done exactly the same thing”.

Gregor McGuckin - his Biscay 36 Hanley Energy was dismasted after rolling in the southern Indian Ocean in the Golden Globe Race

Gregor McGuckin - his Biscay 36 Hanley Energy was dismasted after rolling in the southern Indian Ocean in the Golden Globe Race Against all odds - Hanley Energy struggling along under jury rig

Against all odds - Hanley Energy struggling along under jury rig Gregor McGuckin receiving the Rod Stephens Trophy from CCA Commodore Bob Medland in the NYYC, March 2019.

Gregor McGuckin receiving the Rod Stephens Trophy from CCA Commodore Bob Medland in the NYYC, March 2019.

In our current Lockdown situation with its growing economic crisis, we can take encouragement not only from the simple but inspirational words of Rod Stephens Trophy awardee Gregor McGuckin, but also from the story of the yacht design partnership of Sparkman & Stephens, and how it got going and kept going.

Several people were involved in it, but the principals were yacht broker Drake Sparkman, whose role was to do the marketing and sell the existing yachts of potential clients who could then contemplate commissioning a new design from the 21-year-old Olin Stephens who had trained with established designer Philip Rhodes, while the input on the rig and other aspects of seagoing requirement and construction were to come from his even younger brother Rod, who had trained in boatbuilding with the renowned Henry Nevins yard on City Island in New York.

It was very much an enterprise infused with the huge energy of New York, and it was with the mood of that city’s special enthusiasm and can-do approach that Sparkman & Stephens opened for business in the city on October 28th 1929. It was accepted that Manhattan was going through an economic downturn at the time, but it was reckoned to be no more than a blip until next day, October 29th. That’s when the blip became the Wall Street Crash.

Fortunately, the Stephens brothers’ father, Roderick Senr, was the son of a man who had been in the very basic business of being a coal merchant in the Bronx. Nowadays we’d probably glamorise that by describing him as an Energy Commodities Broker, but whatever, he was very successful in business, thus enabling his son to sell a much-expanded business in 1928, and his talented grandsons to be raised in a way which turned them into classic New England preppies reminiscent in their style of the Kennedy clan. And when push came to shove, the coal business was an essential whose wealth survived the crash even while the glitzy investment firms of top yachties were going belly up, so it was Roderick Senr who financed the essential new breakthrough boat for the firm, the 52ft offshore racing yawl Dorade in 1930.

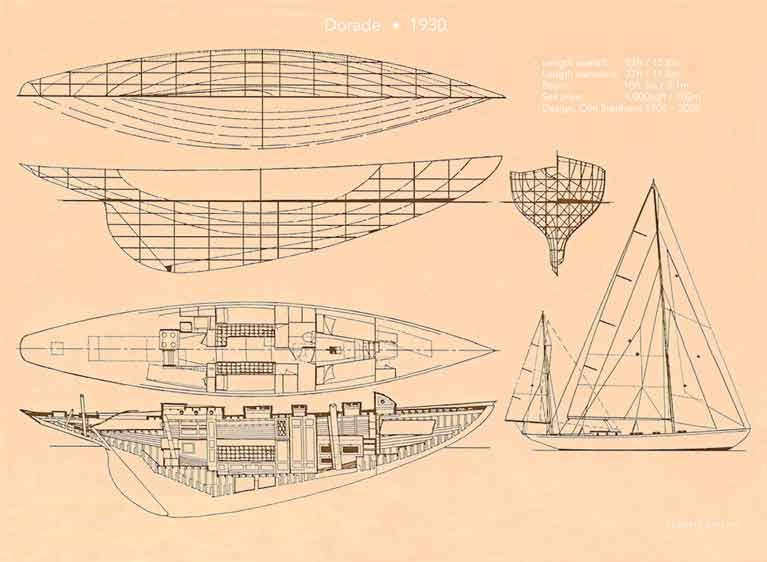

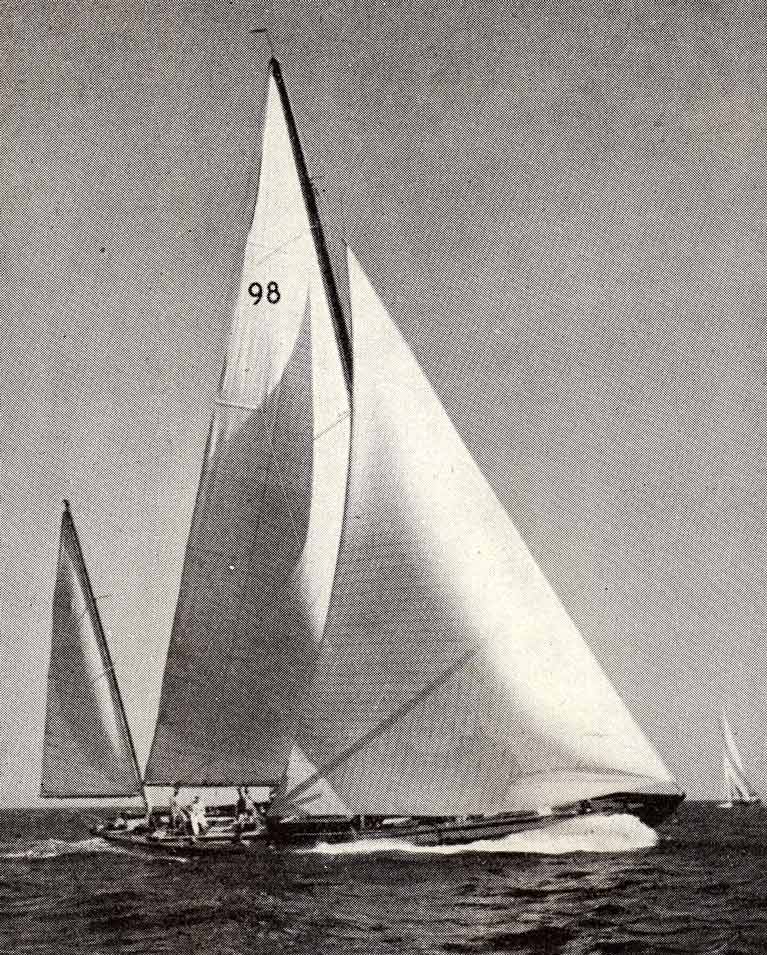

The pioneer. The successful 52ft Dorade of 1930 was quite conservative in concept, with a hull shape which gave the nod to the lines of a schooner. But her combination of top-quality features and good sails on a properly set-up rig provided a world-beating performance which saw two Fastnet Race wins, a Bermuda Race win and Transatlantic Race victory

The pioneer. The successful 52ft Dorade of 1930 was quite conservative in concept, with a hull shape which gave the nod to the lines of a schooner. But her combination of top-quality features and good sails on a properly set-up rig provided a world-beating performance which saw two Fastnet Race wins, a Bermuda Race win and Transatlantic Race victory

In 1931 the brothers raced her Transatlantic and won, and then raced her in that year’s Fastnet Race, and won it too. Olin was just 23, while Rod was 21, and while they were full of life and good company, they were mature beyond their years, and developed a system whereby Olin was the lead helm and – notionally at least – in overall command, while Rod was in charge of the rig, sail-handling and more or less everything forward of the cockpit.

Dorade’s crew, with Rod Stephens front left, and his brother Olin centre, with dark glasses

Dorade’s crew, with Rod Stephens front left, and his brother Olin centre, with dark glasses

It was a division of responsibilities which was reflected in the structure of Sparkman & Stephens, which grew slowly though surely in the depression-laden early years of the 1930s, even though under Rod’s command Dorade had won the 1932 Bermuda Race overall. Despite that success - which might have led to hopes of new boats with new owners - in 1933 it was still with Dorade that they returned to Europe for another Fastnet win. But by 1935 there was more life in the market, and an enthusiastic and wealthy New York department store President, Philip LeBoutillier, commissioned the building of an up-dated Dorade - the 54ft Stormy Weather - for the 1935 season, and this time Rod was the senior presence from the S&S office as they did another Transatlantic Race and Fastnet campaign, getting another double win with what Olin was subsequently to describe as his favourite of all his many designs, for they now were appearing in increasing numbers.

Stormy Weather, the star of 1935, and Olin Stephens’ favourite design. Rather than being a huge advance on Dorade, she was more a matter of incremental improvements made on proven successful features

Stormy Weather, the star of 1935, and Olin Stephens’ favourite design. Rather than being a huge advance on Dorade, she was more a matter of incremental improvements made on proven successful features

So confident was everyone in Stormy Weather’s powers that they brought her home to Long Island Sound directly from Plymouth after the Fastnet, successfully sailing westward straight across the North Atlantic despite the imminence of Autumn and some very testing weather. But this stage Rod’s overseeing of the rig and sails was making its mark more than ever, everyone had total confidence in this key element of a remarkable offshore racer, and while her hull design was special with that unmistakable Olin Stephens look, it was still of quite conservative type with links to proven schooner forms - thus it was Rod’s development of the rig and sails which ensured that Stormy Weather had the edge.

He certainly has an eye for a good-looking yet effective rig in which each element was in harmony with the rest of the setup, and his contribution to the increasing acceptance of Sparkman & Stephens designs during the 1930s was on a par with that of Olin, though it was the older brother who was largely the face of the firm.

A rare enough sight – Rod Stephens in a suit in the office. He much preferred hands-on tasks in the workshop

A rare enough sight – Rod Stephens in a suit in the office. He much preferred hands-on tasks in the workshop

Experienced competitive sailors increasingly recognized the quality and performance of the firm’s creations, but for the wider sailing public –and the public at large – it was the America’s Cup which was the supreme arena for sailing competition, and in those post-Herreshoff years, the US defenders tended to be conservative in selecting the designers for their new J Class Yachts.

For the defence of 1934 with America’s hopes resting on the Vanderbilt-owned Rainbow, the design was by the slightly eccentric Starling Burgess (1878-1947), whose reputation was largely based on the all-victorious 70ft schooner Nina of 1928. and several successful International Metre Rule boats, while he came with the pedigree of being the son of renowned yacht designer Edward Burgess. He was equally interested in aviation and advanced car design, but that’s as may be - the fact is that Rainbow almost lost the cup to Thomas Sopwith’s clearly better Charles E Nicholson-designed Endeavour.

Nevertheless, with so much at stake, the defenders still erred towards caution for the designer of 1937’s defender. Heaven only knows what pork barrel sailing politics went on behind the scenes to settle the matter, but in due course, it was announced that Olin Stephens would assist Starling Burgess in creating the design for the 137ft Ranger, the biggest J Class boat ever to be built.

The magic almost-hidden ingredient in all that was that Rod Stephens would be not only the lead man in creating Ranger’s rig, but he was also the overseer for sail-handling This included one of the biggest spinnakers ever seen, with a spinnaker pole which seemed to go over the horizon. He and Olin sailed on Ranger for the defence, with the hyper-fit Rod in charge of the deck, and quietly confident of facing the challenge of taming that massive acreage of spinnaker, which had all the makings of being a real widow-maker.

“The Widow-Maker” – controlling Rangers enormous spinnaker with the equipment available in 1937 was not a challenge for the faint-hearted

“The Widow-Maker” – controlling Rangers enormous spinnaker with the equipment available in 1937 was not a challenge for the faint-hearted

In the end, Ranger was so clearly out-performing Sopwith’s Endeavour II that the mood on the American boat was almost light-hearted, so much so that Rod Stephens was allowed to bring aboard one of his few self-indulgences. He neither drank nor smoked, but he enjoyed playing the accordion, and as the mighty Ranger was proceeding across the sea in stand-down mode, it was sometimes to the accompaniment of sailor’s tunes from the man himself, the ultimate sailor.

Believe it or not, this is Rod Stephens playing his accordion aboard the successful America's Cup defender Ranger in 1937

Believe it or not, this is Rod Stephens playing his accordion aboard the successful America's Cup defender Ranger in 1937

By the late 1930s, the firm of Sparkman & Stephens was well-established with a steady and profitable line of very high-quality one-off yachts which had the firm’s hallmark of the elegant Olin Stephens hull, and set above it an unfussy Rod Stephens rig which seemed to effortlessly unite maximum sail area with minimal rigging intrusion, a very delicately-judged balance which was Rod Stephens’ speciality and was well seen in Henry Taylor’s 1938 Bermuda Race-winning 72ft Baruna – reckoned by many to be Olin Stephens most beautiful design - and in Vanderbilt’s 12 Metre Vim. When Vim appeared in Europe in 1939, she was light years ahead in rig technology and won 19 races out of 28, with a performance so good that when the America’s Cup reappeared in the 1950s with racing in Twelve Metres, Vim was still competitive against the newest boats.

Henry Taylor’s 72ft Baruna, winner of the 1938 Bermuda Race, waa a classic example of Olin Stephens beauty of hull allied with Rod Stephens elegance and efficiency of rig

Henry Taylor’s 72ft Baruna, winner of the 1938 Bermuda Race, waa a classic example of Olin Stephens beauty of hull allied with Rod Stephens elegance and efficiency of rig

That size-descent from J Boats to 12 Metres was brought about by the world’s reduced circumstances after World War II from 1939 to 1945, and though America wasn’t drawn in until 1941, they had thrown their technology and manpower into the battle with full enthusiasm. Rod Stephens was almost immediately on military and naval work, and while he might have preferred to have been at sea, his war effort is best remembered for his invention of the amphibious DUKW, aka “The Duck”.

One of the Viking Splash amphibious craft in Dublin. Rod Stephens made a major input into the concept and development of these key vehicles during World War 2

One of the Viking Splash amphibious craft in Dublin. Rod Stephens made a major input into the concept and development of these key vehicles during World War 2

You don’t have to go very far to see one in Dublin, as they’re the machines used for the Viking Splash tours. But as a versatile vehicle of warfare, these 2.5-ton six-wheeled “truck-boats” were hugely useful, so much so that more than 21,000 were built by General Motors, and all of them emerged from a re-direction of the ingenious mind of Rod Stephens.

After World War II, there was a further golden age for Sparkman & Stephens, and while the firm’s contribution to several successful America’s Cup defences in 12 Metres is well-known, perhaps the most telling aspect of the 1950s was in how Carleton Mitchell’s 39ft Finisterre came to be one of the best-known S&S creations. Finisterre was to win the Bermuda Race three times in a row in 1956, 1958 and 1960, but until she was built in meticulous detail in 1955-56, Carleton Mitchell had preferred Philip Rhodes designs.

Carleton Mitchell’s 39ft Finisterre in 1956, when she won the first of three Bermuda Races. Mitchell’s previous yacht had been designed by Philip Rhodes, but it was Rod Stephens’ expertise with rigs and rigging which led to him placing the contract for Finisterre with Sparkman & Stephens

Carleton Mitchell’s 39ft Finisterre in 1956, when she won the first of three Bermuda Races. Mitchell’s previous yacht had been designed by Philip Rhodes, but it was Rod Stephens’ expertise with rigs and rigging which led to him placing the contract for Finisterre with Sparkman & Stephens

Yet there was little to choose between Rhodes and Olin Stephens except that Olin Stephens brought Rod with him to oversee every aspect of the rig, and that was the clincher for Mitchell, with Finisterre’s performance under her very determined owner setting Sparkman & Stephens on a pedestal above all others.

But as is the way of things, it was a senior position which other designers and new design developments were always ready to challenge, yet S&S stayed up with the curve with their first fin-and-skeg design for the 40ft Deb in 1963. She was McGruer-built in Scotland for a remarkable Yorkshireman called Eric Barker, and in due course became David Hague’s Dai Mouse III racing with ISORA.

Dai Mouse III (centre) with some of the ISORA fleet in Howth in the 1970s. Designed as Deb in 1963, she was Sparkman & Stephens first fin-and-skeg boat. She is now Tom & Vicky Jackson’s internationally-known Sunstone. Photo: W M Nixon

Dai Mouse III (centre) with some of the ISORA fleet in Howth in the 1970s. Designed as Deb in 1963, she was Sparkman & Stephens first fin-and-skeg boat. She is now Tom & Vicky Jackson’s internationally-known Sunstone. Photo: W M Nixon

Since then Dai Mouse II has become much better known as Tom & Vicky Jackson’s far-voyaging Sunstone, but in the 1970s with ISORA racing, the beautifully-varnished Dai Mouse III regularly found herself sharing berths with fishing boats in the then-rather-chaotic harbour of Howth, which was how Rod Stephens found the place when he made a visit on May 11th 1970 to advise S&S 34 owners and crews on how to optimize the rigs and performances of their boats.

That a sailor and marine technician of such distinction found himself in this situation was reflective of the rapidly-changing marine industry, for although Sparkman & Stephens had shown themselves well able to design popular production yachts such as the Swan 36 and her many successors for the burgeoning fibreglass boat-building industry, it only provided a fraction of the income generated by intensive one-off masterpieces, and Rod Stephens reckoned that getting out and meeting the new series-produced customers in their home ports was essential for keeping the show on the road.

The S&S 34 was remarkably successful, even if her unrivalled windward ability meant she’d a certain weakness reaching and running. But by the time British Prime Minister Ted Heath won the 1969 Sydney-Hobart Race with his S&S 34 Morning Cloud, the production line could scarcely keep up with demand, and technical follow-up seminars by Rod Stephens helped to smooth the bumps in the road.

Most of the boats were called Morning something-or-other, as the marque innovator Mike Winfield had started it all with a boat called Morningtown. But the Irish – who had been in ahead of Heath with their orders – managed to be obtuse in this, with Noel Speidel of Malahide and Howth calling his S&S 34 Malaise – ‘Morning Sickness” – geddit? - while Jack McKeown of Dun Laoghaire, where he was Commodore of the Royal St George YC, somehow acquired one called Korsar, which we were assured was so named because korsars or corsairs were notorious for morning raids.

Not quite the lap of luxury….Noel Speidel’s S&S 34 Malaise and Jack McKeonw’s sister-ship Korsar at the fish quay in Howth fifty years ago, awaiting the attention of Rod Stephens. Photo: W M Nixon

Not quite the lap of luxury….Noel Speidel’s S&S 34 Malaise and Jack McKeonw’s sister-ship Korsar at the fish quay in Howth fifty years ago, awaiting the attention of Rod Stephens. Photo: W M Nixon

Be that all as it may, here we were a good fifty years ago on the grey morning of May 11th1970 – it was also a Monday – and there were Malaise and Korsar alongside the fishing pier in what was then a totally open Howth Harbour with no sensible boundaries between its many uses. The two boats were berthed as near as possible to the then premises of Howth Yacht Club (now Aqua Restaurant), and offshore sailing legend Rod Stephens was expected to clamber down a filthy quayside chain, with small footholds in the quay-face stonework, in order to give a teach-in on S&S 34 tuning.

Fortunately, Frank Hendy, the HYC boatman realised the absurdity of the situation and stationed himself with the club launch at the nearby steps. Those steps may have smelled mightily of fish, but when the great man arrived, he could be conveyed in some safety and dignity to the two little boats, while those of us who knew of Dorade and Stormy Weather and Ranger’s spinnaker and Baruna and Vim and Finisterre and all those legendary 12 Metres, well, we just kept our thoughts to ourselves, and concentrated on absorbing at least some of the intense flow of pure gold information and example which was coming our way.

Those who benefitted from direct interaction with Rod Stephens included Jack Mackeown, John Bourke, Dick Lovegrove, and Arthur O’Neill from Korsar, while Malaise’s personnel were Noel Speidel, Brian Hegarty, Bob Fannin, Tom O’Gorman and Teddy Chandler, and in addition to the morning’s intensive technical session, we all went sailing with the great man in the afternoon.

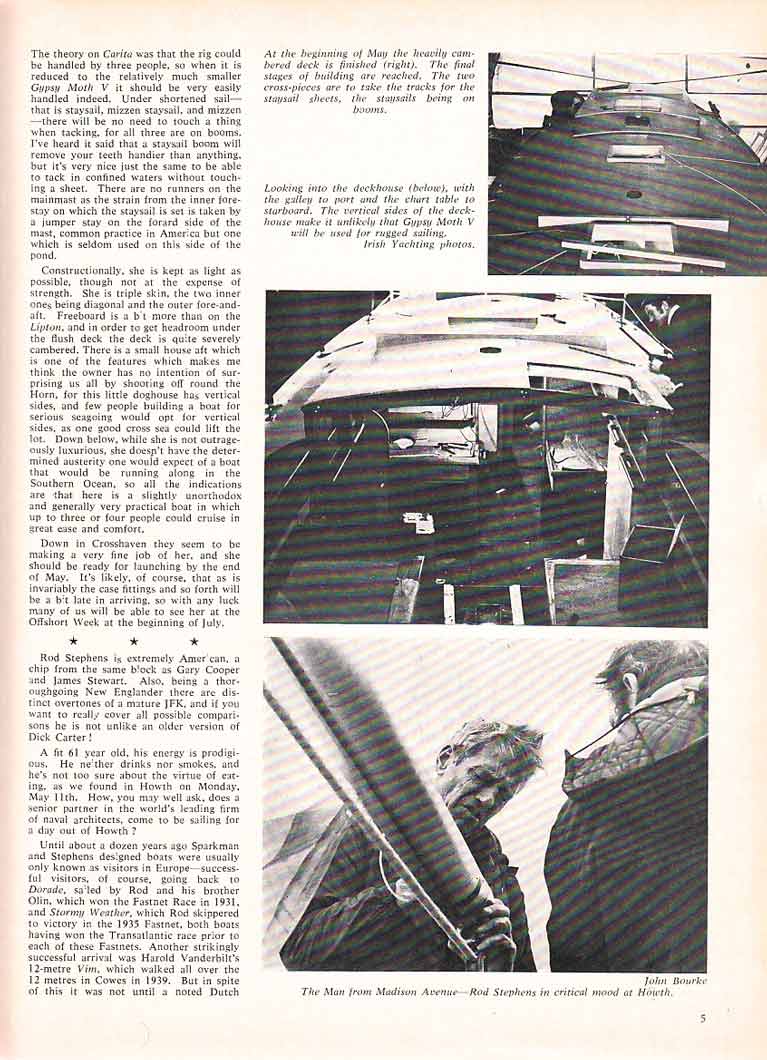

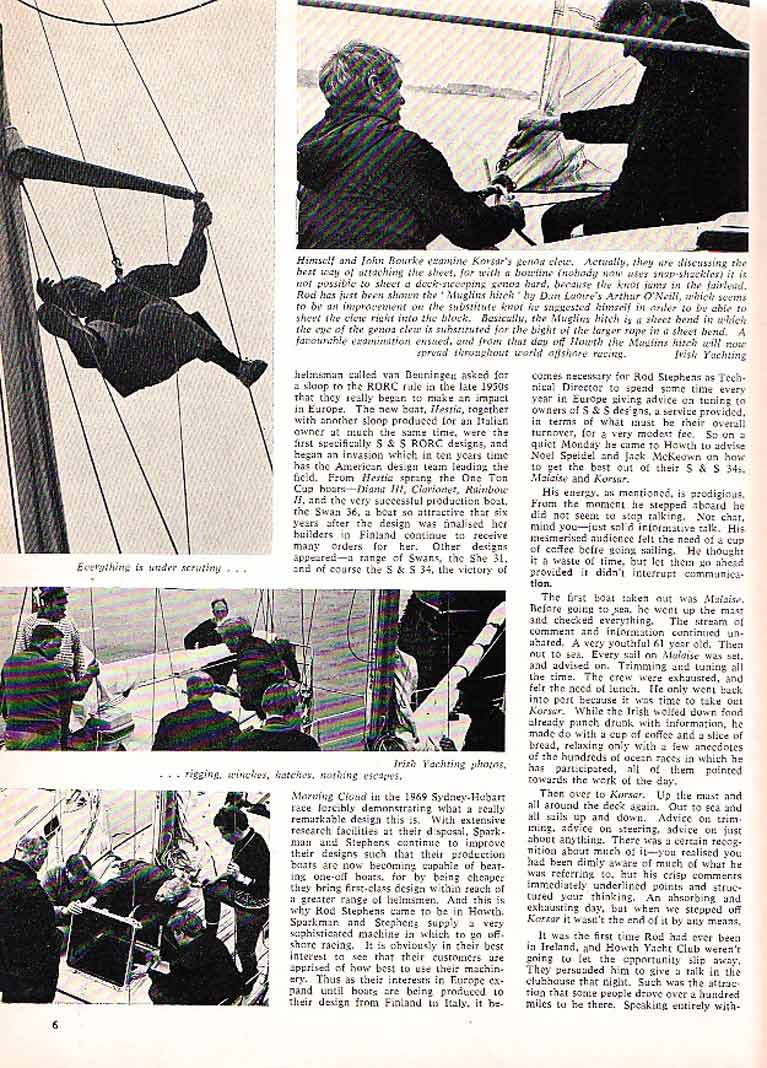

A page from the Seascapes column in the June 1970 Afloat Magazine, in which the second story is about Rod Stephens’ visit to Howth – the lead piece is about Francis Chichester’s Gypsy Moth V building in Crosshaven in 1970, and we’ll return to that another day

A page from the Seascapes column in the June 1970 Afloat Magazine, in which the second story is about Rod Stephens’ visit to Howth – the lead piece is about Francis Chichester’s Gypsy Moth V building in Crosshaven in 1970, and we’ll return to that another day

Then that evening Howth YC was given a friendly yet informative talk by Rod Stephens to a packed house, and he brought everyone with him by first enquiring of us what was the most important part of any rig? Then he held aloft a tiny piece of metal which he described as a cotter pin, and we knew as a split pin, but whatever you called it, he said that the rigs of 1970 were no more than a hazard unless there was a properly-installed cotter pin in every place where it was intended, nd that made them Number One because all the fancy tuning after that was a waste of time without the cotter pins to maintain the optimal set-up.

In its way, that wonderful evening was a highlight in the history of Howth Yacht Club. It gave us a glimpse of the great outside world, and encouraged us in our own sailing. We may look back in wonder at the condition which obtained in Howth Harbour until the massive re-configuration and dredging of 1980 led to the new marina in 1982 and the new Howth YC building in 1987, but through the late 1960s and 1970s, we just got on with making the best of what we had. And maybe it was what was needed, for in 1973 no less than two of the three boats in the Irish Admirals Cup were from Howth with Mungo Park’s Chance 37 Tam O’Shanter winning the Gull Salver for best-placed Irish boat, and throughout the ’70s the Howth input into ISORA and RORC racing was prodigious. In looking back, it’s clear that the only real option was to go sailing, as Howth Harbour was far from being the comfortable gastronomic honeypot it is these days, while back in the 1970s we were encouraged seaward the memories of Rod Stephens’ visit.

Whatever, I wrote up the Rod Stephens visit to Howth with considerable enthusiasm for the Afloat Magazine issue of June 1970, and before the month was out an international payment for a year’s subscription to Afloat magazine came from one Roderick Stephens Senr in America. It seems the son of the Energy Commodities Broker from the Bronx was still very much with us, and wanted to support a magazine which wrote as much about his high-achieving sons as interesting people as it did about the boats that they created.

The second page of the June 1970 report on Rod Stephens in Howth – he seemed to spend as much time aloft as he did on deck.

The second page of the June 1970 report on Rod Stephens in Howth – he seemed to spend as much time aloft as he did on deck. Final section of the 1970 report on Rod Stephens, following which we went on into some powerboat coverage

Final section of the 1970 report on Rod Stephens, following which we went on into some powerboat coverage

But the ultimate angle on Rod Stephens was to come much later from Sheila McCurdy, who was to become the first woman Commodore of the Cruising Club of America, and at the awards ceremony attended by Gregor McGuckin last year, she received the Richard Nye Trophy for services to the CCA. It was her father Jim McCurdy – clearly of County Antrim and possibly even Rathlin Island descent – who had taken over the Philip Rhodes design practice, and soon had created the all-conquering 48ft Carina for Richard Nye.

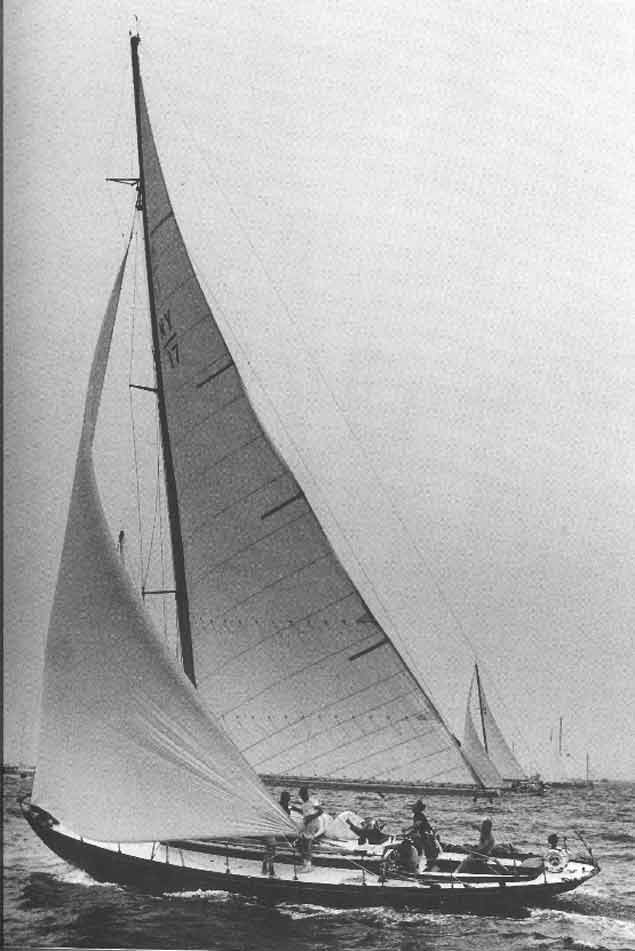

Jim McCurdy had his own-designed Heritage 35 Selkie – near enough a miniature Carina – and one special weekend in her childhood when it was Sheila McCurdy’s birthday, they went for a little Long island Sound cruise. And when they anchored up for the special evening, there anchored alongside was Rod Stephens own S&S-designed NY 32 Mustang, for although Olin Stephens relaxed through playing tennis, Rod Stephens so loved sailing that he had his own beautifully-maintained boat, his only regret being that he didn’t get to sail Mustang as often as he might have liked.

Anyway, with such good company to hand, Rod and his Mustang crew were invited aboard Selkie for the birthday party, though as everyone settled in Jim McCurdy explained it was rather basic - they’d overlooked the candles for the birthday cake, but he was sure everyone could imagine them being in place.

“Please excuse me for a minute or two” said Rod Stephens as he disappeared up the companionway to hop into his dinghy, and row back to Mustang. It seemed only seconds had elapsed before he returned, complete with a handy little pack of birthday cake candles.

An exceptionally well-equipped cruiser-racer – Rod Stephens personal NY32 Mustang, with himself at the helm.

An exceptionally well-equipped cruiser-racer – Rod Stephens personal NY32 Mustang, with himself at the helm.