Displaying items by tag: Dunleary Lifeboat Project

Minister of State for Heritage Malcolm Noonan has visited the former lifeboat named Dunleary, which is the focus of a refit project in its home harbour.

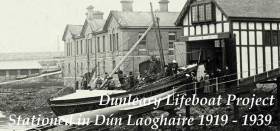

The Watson-class lifeboat was stationed at what was formerly Kingstown, Co Dublin, from December 1919 to July 1939, during which it recorded 23 launches and saved 55 lives.

The RNLI then moved it from Dun Laoghaire to Lytham in Britain, where it was stationed from 1939 to April 1951 and launched 58 times to save 30 lives.

The vessel was then sold out of service at Sunderland and converted to a motor sailor by Lambies Boat Builders.

As Mr Noonan was told by Senator Victor Boyhan (Ind), who hosted the visit, the Dunleary Lifeboat Project is a not-for-profit organisation which is “committed to promotion of the maritime heritage”.

It says its immediate aim is to “establish a suitable premises in a maritime environment to incorporate ongoing restoration and maintenance of this vessel, and other vessels of historical and heritage value for the future generations”.

“Dunleary was the first motor lifeboat provided by the civil service fund and has an excellent wartime rescue history. She was built in 1919 and was named by the Countess of Fingall in honour of her launching place,” it says.

The project is seeking donations from members of the community and local businesses for the restoration project.

Senator Boyhan thanked Minister for Heritage Malcolm Noonan and the Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown chief executive Frank Curran for their support for the marine heritage restoration project.

An important piece of Ireland’s maritime history, the 100-year-old Dunleary Lifeboat, is the subject of a new exhibition in DLR LexIcon from this Monday 21 January to Monday 4 February.

As previously reported on Afloat.ie, this exhibition — which has an open launch this Monday evening (21 January) — is being presented by The Dunleary Lifeboat Project in partnership with students from Sallynoggin College of Further Education.

The Dunleary Lifeboat No 658 was built in 1919 and stationed in Dun Laoghaire Harbour from 1919 until 1937. In that time she saved 55 lives.

This boat is unique as she is the sole survivor of the first 11 production boats dating to this time.

She was the first motor lifeboat provided by the civil service fund and has an excellent wartime rescue history across the Irish Sea at Lytham, south of Blackpool, where she served from 1937 to 1951. She has made a total of 81 launches, saving 85 lives.

The boat was recently brought back from the UK, where she was destined to be scrapped.

A group of local enthusiasts recognised the important historical significance of the vessel and formed a community association: the Dunleary Lifeboat Project.

This group garnered enough support to safely transport the boat back to the Coal Pier in Dun Laoghaire, where she is currently stored.

Their goal is to restore her to full seagoing condition so that she can be used as a heritage asset in the harbour, taking groups of visitors on short historical trips.

The exhibition traces the story of the Dunleary Lifeboat, her return to the harbour, her future as part of Dun Laoghaire’s rich maritime culture, and includes:

- Display of copies of the building plans, the originals of which are held in the Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

- A copy of the earliest photograph of the boat. This original glass plate photograph is in the RNLI Archive collection.

- Accounts of her initial journey from Cowes to Dun Laoghaire as well as the official launch.

The Dunleary Lifeboat is currently awaiting a final certificate of assessment before restoration and fit-out to her former glory can begin.

New Exhibition On Dunleary Lifeboat Project At DLR Lexicon This Month

The Dunleary Lifeboat Project is the subject of a new exhibition at the DLR Lexicon in Dun Laoghaire from next week.

Running from Tuesday 22 January to Monday 4 February, the exhibition is being held in partnership with Advanced Tourism & Travel students from Sallynoggin Senior College.

Ossian Smyth, Cathaoirleach of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, will be on hand for the launch night on Monday 21 January from 6pm where Mary Mitchell O’Connor, Minister of State for Higher Education, will also be the keynote speaker.

As previously reported on Afloat.ie, the original RNLB Dunleary was stationed in the South Dublin harbour from 1919 to 1937, and returned to its former haul in August of 2019 thanks to the efforts of a local restoration group.

For more on the project and the latest updates, see the group’s Facebook page.

Dunleary Lifeboat Returns To Home Port After 80 Years

#Lifeboats - A lifeboat once stationed in Dun Laoghaire almost a century ago has returned to the harbour thanks to the efforts of a local restoration group.

The Dunleary was secured in the Coal Harbour yesterday (Tuesday 15 August) after transport from Amble in Northumberland, where it had been been dry-docked for many years.

Now the Dunleary Lifeboat Project, whose efforts brought the vessel back to Dun Laoghaire, are gearing up to restore the lifeboat to its former glory — and are calling for donations to cover the costs of transport and storage, as well as support the next vital stages of the project.

RNLB Dunleary was stationed in the South Dublin port from 1919 (when it was still known as Kingstown) till 1937, during a tumultuous and historic time for the island of Ireland.

According to the UK’s National Historic Ships register, the Dunleary launched 81 times in its two decades at its titular port, saving 85 lives.

Following its time in Dublin Bay 80 years ago, the Dunleary moved across the Irish Sea to the RNLI station at Lytham St Annes in Lancashire — where it helped save 28 lives during the Second World War.

Some time after that, the boat was decommissioned and converted into a motor sailer, and in 1970 came into the possession of Jack Belfield and Pat Jopling of Amble, whose plans to restore her as a work/pleasure boat were not to be.

After her husband Jack’s death, Pat Jopling kept the Dunleary in the boatyard she owns, though in 2014 its future was rendered uncertain due to a planned redevelopment.

Previous moves to relocate the boat to Lytham fell through, but that allowed Brian Comerford and the Dunleary Lifeboat Project to step in and negotiate her return to the port she served almost 100 years ago.

How that the Dunleary is back in Dun Laoghaire, the most pressing concern is securing with the assistance of the Dun Laoghaire Harbour Company of a suitable premises where the restoration work can begin.

For more see the Dunleary Lifeboat Project website, and check the group’s Facebook page for the latest updates.