Displaying items by tag: Wolfhound

Video has recently surfaced online of ocean researchers’ encounter in the Atlantic with an abandoned Dun Laoghaire yacht — one that was the subject of headlines a decade ago.

It’s nearly 10 years since Alan McGettigan and crew were rescued from their Swan 48, Wolfhound, some 70 miles off the coast of Bermuda in February 2013.

McGettigan — who died in November 2022 — was joined by fellow Royal Irish Yacht Club members Declan Hayes and Morgan Crowe as well as Tom Mulligan from the National Yacht Club on the yacht, which had suffered both power and engine failure amid stormy conditions while en route from Connecticut to that year’s RORC Caribbean 600.

Some time later in 2013, a vessel from the Ocean Research Project happened upon the ghost yacht “somewhere in the Atlantic”.

Unaware of the previous incident, the team — including experienced solo circumnavigator Matt Rutherford — noted the boat’s “strange behaviour” before approaching and boarding to learn more about its fate.

“I’m afraid to open doors and cabinets,” says Rutherford as he explores the cabin, fearful that he might happen upon the remains of an unfortunate sailor.

Rutherford and his crew mate set up a tow to bring the stricken Wolfhound some 800 miles to Bermuda, but as he explains in the video they were forced to cut it loose following difficulties of their own, which left them becalmed in the Doldrums for nearly four weeks.

IrishCentral has more on the story HERE.

#cruising - Sailing From Bermuda to the Azores on the magnificent yacht Wolfhound III with skipper and lifelong friend Alan McGettigan was an 1,800–mile adventure for Kildare sailor Fin O'Driscoll.

Bermuda is the oldest remaining British overseas territory and the picture postcard town of St. George on the north east corner of the main island is the oldest continuously inhabited English settlement in the new world writes Fin O'Driscoll. The town dates from 1612, when British naval vessel 'Sea Venture' captained by Admiral Sir George Somers was deliberately steered onto a nearby reef to escape a storm. In 1996, the town was twinned with Lyme Regis, in Dorset, the birthplace of Admiral Somers and in 2000, it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Three friends and I travelled from Dublin to St. George in early May where we waited a few days for a boat sailing down from Newport, Rhode Island. Having enjoyed sailing over the years such as cruising in the Med, racing in Dublin bay and coastal trips in the Irish Sea, I knew that this was going to be different. An 1,800 mile crossing from Bermuda to the Azores.

Bermuda has a population of 62,000 and the economy is based on offshore insurance and tourism with the territory enjoying the world's highest GDP per capita for most of the last two decades. The islands have a humid sub-tropical climate and are warmed by the Gulf stream with water temperatures reaching a tepid 22C, making it a wonderful place to swim compared to the chilly Irish Sea. Interestingly, a survivor of the 'Sea Venture' shipwreck was one John Rolfe, whose wife and child died and were buried in Bermuda. Later in Jamestown he married Pocahontas (of Disney fame!), a daughter of the powerful Powhatan, leader of a large confederation of Algonquian tribes in coastal Virginia.

Our vessel, Wolfhound III arrived from Newport on 8th May. She is a magnificent yacht, owned and skippered by Alan McGettigan (RIYC), a lifelong friend from Dublin. I am from Kildare and the three other Irish sailors were William Reilly from Greystones, Barry O'Sullivan and John Campbell from Dublin.

Wolfhound III alongside in St. George

Wolfhound III is a classic Nautor Swan 59' sloop, weighing in at 30 tonnes and sporting an 80 foot mast. She has 4 cabins, can comfortably sleep 10 crew and is complete with a large saloon and galley, a myriad of instrumentation and no less than 14 winches plus 2 grinders on deck! A lot of other boats were arriving for the ARC (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers) 2014 race which was due to leave St. George for the Azores on the 14th so the marina was buzzing. Bermuda is a very expensive place to shop, which we soon found out when we completed our provisioning for 2 weeks at a cost of $2,100 and that excluded any alcohol as she was a dry boat!

Leaving St. George heading East

We departed on Sat 10th May at 14:00 in idyllic sailing conditions and enjoyed three days of fine weather, which allowed us get used to the boat, champagne sailing without the champagne! Three of the crew are keen amateur chefs and so we enjoyed fine cuisine on the high seas. As we headed North East to catch the prevailing winds to the Azores, we ran into heavy weather as forecast. We encountered a large low pressure system, so the westerly winds on the south side of the system swept us towards our destination. Barometer readings dropped 15millibars in 6 hours followed by gusts of up to 40knots and 25 foot seas, which made for an exciting and challenging passage.

Alan McGettigan (left) and article author and crew man Fin O'Driscoll

The crew in full offshore gear, wore lifejackets at all times and were strapped onto lifelines while on deck or in the cockpit. At night we were on two hour shifts and as the boat was rolling a lot, the culinary delights from the galley were replaced by storm rations; Campbell's soup, tinned ravioli and copious amounts of Red Bull to keep us alert through the long nights.

The gales lasted five days and with winds averaging 25 knots our trip log recorded us surfing down big Atlantic rollers at up to 15 knots, which is fast for a cruising yacht. As is the norm in these weather conditions the boat is tested to the limit and Wolfhound III performed admirably. The port jib sheet parted when a large bow wave hit the fully unfurled headsail and a full knock down at 05:15 one morning rolled everyone out of their bunks (except the two on watch) however she righted herself very quickly. We learned later that British boat Cheeki Rafiki was in the same storm system 400 miles to the west of us and unfortunately her four sailors were lost when the keel sheared off and she capsized before they could release their liferaft.

Above and below sailing through big seas

In the two weeks at sea, we saw numerous dolphins, porpoises and several breaching whales. The pods of dolphins had a habit of swimming alongside in the early mornings as the sun rose over the bow, a very therapeutic way to start the day. Yes, the Atlantic Ocean is an unbelievably large and empty place as we saw only one other sailboat and three freighters during our voyage. Sailing at night with full canvas up and steering by the stars across the pitch black ocean is an unworldly experience. Combine that with the sparkling luminous green phosphorescence in our wake, a full moon and scudding black clouds for dramatic effect. On day nine, the winds had abated and the sea was millpond calm so we stopped the boat and all dived in (leaving at least one person on board as we had all seen the film Adrift!) for a mid Atlantic swim. A strange sensation considering the nearest land was 2 kms straight down and the nearest coastline was over 1,000 kms away.

Land Ahoy! On day thirteen the Azores appeared on the horizon and we arrived safely in Horta at 19:00, 12 days and 2 hours (including 3 hour time difference from Bermuda) after a distance of 1,900 miles. After tying alongside in the bustling port, we checked in at immigration and immediately proceeded to Peter's Café Sport, a world renowned crossroads and watering hole for transatlantic sailors. The long awaited hot showers had to wait until the following morning as there were celebrations to be had. After 13 days at sea, it took us all a while to get our land legs back and the occasional stumble was not at all due to the pints of Superbock consumed after our dry boat experience.

The happy crew quayside in Horta

Horta on the island of Faial has the fourth most visited marina in the world and is overlooked by the very impressive 2,350m Mount Pico on the neighbouring island. The Azores are a Portuguese overseas territory and the nine main islands stretch over 230 miles from Flores in the West to Santa Maria in the East. Officially, the islands were discovered in 1431 by Portuguese explorer Gonçalo Velho Cabrall and Christopher Columbus famously stopped over at Santa Maria (named after his ship) in 1493 on his way back from discovering the New World. During the 18th and 19th century the islands were host to many prominent figures, including Chateaubriand, the French writer who passed through upon his escape to America during the French revolution and Mark Twain published "The Innocents Abroad" in 1869, a travel book, where he described his time in the Azores. The islands straddle an active junction between three of the world's largest tectonic plates (the North American Plate, the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate) resulting in a lot of seismic and volcanic activity in this region of the Atlantic.

After a memorable night celebrating in Horta, the four of us left Wolfhound III and flew back to Dublin via Lisbon. Following the scheduled crew change, the boat has since sailed the final 850 miles onto Lagos in southern Portugal, completing her full transatlantic crossing from the US mainland to Europe. A real marine adventure and sailing the Atlantic is definitely one for the bucket list!

Risk Outweighs Reward to Salvage Abandoned Yacht as Wolfhound Found Again

#wolfhound – On board the research vessel AULT, a specially outfitted vintage Tom Colvin-designed 42-ft. steel-hulled sailboat transformed into a scientific mobile observation platform, was celebrated solo circumnavigation of the Americas in 2012 record holder Matt Rutherford and marine environmental scientist Nicole Trenholm. It was day 47, July 22nd, 2013, at sea in the North Atlantic Sargasso Sea Gyre conducting data collection with a manta net of marine debris, a 3-month journey by Matt's Annapolis-based non-profit Ocean Research Project, and reporting atmospheric and oceanic observations as a Voluntary Observing Ship for marine agencies. (See at www.oceanresearchproject.org )

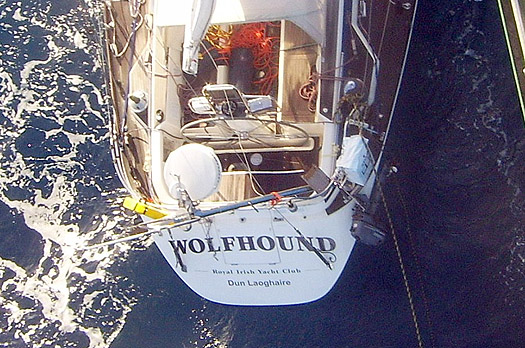

After a very long day, suddenly they noticed a sailboat with no sails that seemed to be drifting. Thinking someone aboard may need assistance, Matt and Nicole changed course to investigate. As they passed close to the vessel no one answered Matt's hailing. He jumped into a flimsy kayak they had brought and paddled over to the boat he discovered empty. Boarding he found the owner's name (Alan McGettigan) and his insurer, he called both about the abandoned 48-ft. Nautor Swan named Wolfhound previously reported sunk in a severe storm after the owner and crew of three rescued and brought to the Irish coast. She did not sink however and reappeared some 800 miles southeast of Bermuda until spotted once again.

Nicole Trenholm, who was first to spot the abandoned vessel on the horizon, later said that the resulting encounter would prove to challenge their strength both physically and mentally and inevitably handicap their ability to promptly make landfall for repairs. The following is an excerpt in Matt's own words from a posting at sea of their attempt to 'capture' the Wolfhound.

WOLFHOUND

Excerpt from Ocean Research Project to AFLOAT.ie with permission

The next day I returned to Wolfhound and pumped all the water out of the bilge. I had to secure the mast because the forestay and backstay were broke. I secured the mast with a few halyards, the mast wouldn't be able to support a sail but at least the mast wasn't going to fall down. She was dragging an anchor which I pulled back on board and tied off. I also took down the ripped up main sail and stowed it away inside the cabin. I had done everything I could to secure the Swan.

Marine environmental scientist Nicole Trenholm, who was first to spot the abandoned vessel on the horizon

Nikki and I discussed our game plan. We didn't have enough fuel to tow Wolfhound all the way to Bermuda so the next day I was going to kayak back to the Swan and pump out its fuel tank hoping to get at least 30 gallons of diesel. The next day I disconnected one of my ships batteries placed in the kayak and paddled back to the Swan. I used a waste pump that I found which was brand new still in its box and my big group 31 battery that I brought and started to pump Wolfhounds fuel tank dry. I was disappointed when I only got 12 gallons of diesel. I tried to bring back a jerry can with the Kayak but the Kayak flipped, I was being drug behind the Swan with one hand on the kayak and the other hand on the swim ladder. I dragged myself and the kayak back onboard and decided there was no way to get my battery and three jerry jugs back to my boat using the little kayak. After searching around I found a Zodiac inflatable on Wolfhound so I pumped it up and threw it overboard. At least now I have a good way to shuttle the 12 gallons of diesel and my big battery back to my boat. Then craziest thing happened. On the way back to my boat the bottom fell out of the dingy. One minute I'm just rowing along and the next minute I'm looking down at nothing but water. My 100 pound battery I brought with me had a line attached to it and the line nearly rapped around my leg. If it had it would have taken me to the bottom of the ocean with it. I struggled to get back to my boat and climbed aboard, but I did manage to save the 3 jerry cans that had the 12 gallons of fuel in them. Nikki and I set aside 20 gallons of fuel in reserve and decided if we can't get Wolfhound to Bermuda with the remaining fuel then we cut her loose and use the 20 gallons of reserve fuel to get to Bermuda without her.

The next day we spotted a freighter and asked the freighter if it could spare 50 gallons of diesel. At first they were hesitant but when the saw that we were towing a sailboat the freighter agreed to help. I had to pull up next to a slow moving freighter, stay 10 feet from its hull and maintain a prefect course in order to get the fuel. It took every bit of skill I had to hold my boat in that position for an hour as the guys on the freighter lowered one jerry jug at a time down to Nikki. It was absolutely nerve racking. You never want to be that close to a freighter in the open ocean, but if we could pull it off we would have enough fuel to easy tow the boat to Bermuda.

As we pulled away from the freighter we were all smiles. We now had enough fuel to motor to Bermuda. We were going to pull it off. A few hours later I noticed our RPM gauge was jumping around and the engine was starting to struggle. I backed down the throttle and the engine died immediately. I said to Nikki 'we must have got dirty diesel, I'll change the fuel filter'. I changed both fuel filters and bled the air out of the engine and she still wouldn't start. It was getting dark so I thought it best to get some rest and deal with it tomorrow. The next day I took my oil extraction pump and jury rigged it to my primary fuel filter. This way I could pump all the dirty fuel out of the fuel tank through the fuel filter and into jerry jugs. By doing this I would clean all the fuel and then I could pour it back in the tank. I had to sacrifice two more fuel filters but it went remarkably well and now all the fuel was clean. I only had one fuel filter left but we should be okay. I reconnected the primary fuel filter to the engine, we bled out the air and — nothing. The engine still wouldn't start. I spent the next 36 hours bleeding and re-bleeding my engine until I had to finally except that the fuel I got from the freighter was so bad that it ruined my fuel injection pump. There is no way to fix that out at sea, my engine was dead.

Matt Rutherford on the bow of the research vessel AULT, a specially outfitted vintage Tom Colvin-designed 42-ft. steel-hulled sailboat

That changed everything. Now the only hope we had to get Wolfhound to Bermuda was to get her engine started. The first thing I had to do was remove the lines that had rapped themselves around Wolfhounds propeller. It took about an hour of hard swimming before I could get all the lines off of Wolfhounds prop. While I was doing that a line rapped around the propeller on my boat. I had to cut lines off of two different boats propellers back to back in the middle of the open ocean. By the end I was covered in scraps and cuts and completely exhausted. After that fiasco I took another one of my ships batteries over to the Swan 48 and got it connected to the ships electric system. I was able get the engine to turn over but I couldn't get it to start. At this point the wind died and my boat stopped but the Swan didn't. I watch helplessly as the Swan rammed my boat putting a dent in the side of my ship. Then it spun around and the tow line rapped around it rudder, so now we were pulling it backwards. It took three hours to finally get the Swan 48 spun back around the right way. As all of this was happening the seas were building. I was still on Wolfhound and Nikki was on Ault. There was no way I would be able to bring my battery back to my boat and from the looks of it I would be lucky to get back at all. I narrowly managed to row the little kayak back to my boat as each wave was trying to flip me.

Again Nikki and I sat down to discuss a new game plan. Between the two boats we had two broken engines and only my boat could sail. We got an accurate weather report from Predict Wind that told us for the next 7 days we had nothing but headwinds and light winds. We tried to tow her under sail into the wind but the combined leeway was pushing us east, further out to sea and away from Bermuda. We knew if we dragged the boat long enough we could get to Bermuda but how long, two weeks, a month? Every day that went by my boat was receiving more damage. That and it is hurricane season, we can't just be out here like a sitting duck. Just as Nikki and I were having this conversation I heard a noise. The towline had rapped itself around my windvane again threatening to rip it off. We are out here to do research not salvage boats. You cannot let greed corrupt good judgment. There comes a point when the risks outweigh the reward. At 4:30pm after 5 long days of towing Wolfhound I cut the line.

We cut Wolfhound free and started making some headway when the halyard on the mainsail failed and for the last 36 hours we have been trying to beat into 15-20 knot headwinds with only a foresail, going nowhere. In a day or two when the wind dies I will climb my unstayed mast to the top and fix the problem. I can't say I want to do it, but it has to be done. After that difficult climb up the mast we will be able to raise our main sail again but then we will be becalmed for 3-5 days. When the wind finally picks back up we will continue back to land.

On the bright side of things, every major sailing trip I've ever done I did with a broken engine so it's nothing new to me. There are no big storms anywhere in the Atlantic (for now) and we have plenty of food and water. We won't be going anywhere for the next 5 days because of the light winds but at least we will have a chance to clean the boat up, fix things and regroup.

Matt Rutherford

Longtime U.S. marine law writer, Joan Wenner, J.D., advises Matt and Nicole arrived safely at their Annapolis homeport in early September after a delay for engine repairs in Bermuda (where they made front page news) and are preparing for a 2014 Artic scientific expedition. Read about them at Ocean Research Project's website and click on About Us. Additional sponsors gratefully sought.

#wolfhound – You can't put a good boat down. Here she is. The lost one. The Irish Swan 48 Wolfhound, doing better on her own than she did with a crew writes W M Nixon.

Nine weeks after she was abandoned in a storm 70 miles north of Bermuda, her crew taken off safely by the Greek ship Tetien Trader, Wolfhound floats on all alone, now 800 miles southeast of Bermuda.

Afloat.ie reader Martin Butler sent the unique photo at the weekend confounding early news reports the craft had sunk.

Going her own way, she's getting near the wide Sargasso Sea, where she might drift for eternity unless somebody brings her in. Highly likely, now that this remarkable pic has gone viral. All things considered, she's looking very well. Her upper boot-top is still showing, so there can't be that much water down below. But we can't tell if her hull is still intact, as she was starboard-side-on for the rescue. So there could well be impact damage away from the camera's eye.

Miraculously, her tall carbon mast is still standing, even though the forestay has broken from the stemhead - you can see it wrapped round the shrouds. And the backstay has also gone, so only the checkstay is holding the rig fore-and-ft. If the checkstay goes, then the mast is likely to break, with the risk of its splintered pieces holing the hull. Meanwhile her mainsail, lying as it was dropped, seems all of a piece. She's a tough old bird. Whoever can get the mostest there the fastest is going to get one very gallant boat. She may be plastic, but Wolfhound has a heart of oak.

Her upper boot-top is still showing, so there can't be that much water down below

And how can she be found again, now that the ship that took the pic has moved on? Let's hope that somebody thought to chuck a mobile phone into her cockpit. It could give a signal, however weak, for a long time - long enough to find her again and put a crew aboard to sail her up to Bermuda, or across to the Azores

Read WM Nixon's full account of the rescue of Wolfhound's crew out now in the Spring issue of Afloat at all good news agents nationwide

Abandon Ship! The Rescue of the Crew of Wolfhound

#wolfhound – Abandon ship!!! Complete with its insistent screamers (that's exclamation marks to you and me), it's such a hoary old nautical cliché that when it happens, you expect awesome background music to roll, with the blackest of black clouds overhead tearing apart to reveal some majestic and divine portent.

But the reality these days is that with well-established International Laws of the Sea in place, and time-tested global rescue procedures working effectively supported by the latest in basic emergency radio communication, once it has moved beyond a life-and-death situation with the rescue achieved, it very quickly becomes a humdrum matter of filing reports, completing forms, and submitting to official enquiries.

Such routine is important for everyone, and not least the rescued. It puts their experiences into perspective, it makes them realise that what has happened to them is not horribly unique, and it gives them a reasonable feeling that while they have suffered an acute personal setback, perhaps it can now be of some benefit to others. By slipping into established post-rescue formalities and analysis, the process of mental and physical recovery can be quietly begun.

Obviously the situation is completely different if there has been loss of life. But happily, in the matter of the rescue of the crew of four from the Irish-owned Swan 48 Wolfhound 70 miles off Bermuda on the morning of Saturday February 9th 2013, apart from one non-acutely wounded hand, there was no serious injury involved. So we can now examine how a very attractive project to take part in the sun-filled RORC Caribbean 600 Race in a fine 12-year-old Swan 48 newly-purchased in New England, and subsequently sail the boat home across the Atlantic to Ireland after cruising the Caribbean, became so totally unravelled in an extreme winter storm in the Gulf Stream.

Alan McGettigan (52) has made his career in the oil and gas exploration business. One of the founders of successful frontline operator Petroceltic, his work has taken him to harsh and volatile places which, if they weren't already dangerous to be in at the time, inevitably became dangerous with their added strategic significance when his prospecting was successful. It was a working life outside normal comfort zones, so as a sailing enthusiast – when he could get the time – he also pushed the limits of the possibilities in cruising.

Alan McGettigan in Dun Laoghaire 27/02/13 Photo: W M Nixon

A dozen or so years ago, he bought a Ron Holland-designed Swan 43 which he called Wolfhound. Though time was initially limited, six years ago he began a long-term cruise aimed at circumnavigating western Europe, beginning with a west-east transit of the Mediterranean in which – unusually – he focused in the early stages on the coast of North Africa.

Being very much part of the Dun Laoghaire sailing community, he has like-minded friends – many of them boat-owners themselves – to make up a crew panel on which he could draw for congenial ship's company, people who in turn were enthused by his interest in going to unusual places. Despite the turmoil in the region, with each succeeding season Wolfhound found herself getting further east, and in time she explored the Black Sea in some detail before – in the summer of 2011 – she shaped her course into the Danube.

But after the worst drought in a hundred years, the great river's levels were so low that Wolfhound's draught prevented them getting any further than fifty kilometres upriver, so they returned to the Black Sea coast, and arranged to lay the boat up afloat for the winter in the attractive Romanian port of Constanta. But then in November, too late to move to another port, Alan had a call from the harbour that they required Wolfhound to be lifted out and laid up ashore, for which the yard would provide the cradle.

Although he preferred her to be afloat in the sheltered little marina, he flew out and supervised the transfer ashore. Then in January the yard was in contact again to say that an extreme winter storm was moving south from Siberia, and there was a danger that boats ashore on the quay would be engulfed in snow and ice. But the weather was already so bad that Constanta airport was closed down. So Alan could do nothing but await the worst as the yard emailed him photos which showed Wolfhound disappearing under her own private iceberg which eventually weighed more than ten tonnes. The cradle collapsed, and the boat sustained further serious damage in falling on her side under yet more snow and ice.

Although badly damaged, she was repairable, yet she would only be acknowledged as a proper Swan if the repairs were done by Nautor Swan themselves in Finland. But that process with its long transportation would be prohibitively expensive. The insurers preferred a yard they'd found in Bulgaria. Eventually, the stalemate was broken with a deal in June, the insurers paying up the insured value, and keeping the damaged boat.

So Alan found himself boatless in June 2012, but with an unexpected accumulation of significant boat-buying resources, as he sold up his shareholding in Petroceltic in 2012. The world was his oyster, or rather his Swan, and he toyed with the idea of an attractive readily-available Swan 60 in the south of France, and a Swan 651 in the UK.

But this resulted in a certain thoughtful sucking-in of the breath among his regular crew panel. They pointed out that if he was seduced into going above a certain size, their cosy all-friends-together-as-equals arrangement would almost certainly be disrupted by the need to carry professional crew, particularly if the boat was going to be moving around exotic and distant locations.

Those of us who mess about in smaller boats are happily untroubled by this critical change of boat management requirements above a certain size. Indeed, it's a problem for which most of us would have scant sympathy. But it is very real for those who have the means and inclination for a larger boat in which they can really cover the ground and get comfortably, if somewhat impersonally, to distant places, if they're prepared to go with the potentially disruptive presence of professional crew making them feel like passengers on their own boat.

"A modern Moonduster". The Frers-designed Swan 48 is nearly 50ft long, and is an up-dated glassfibre sister of Denis Doyle's famous Moonduster

By September 2012, however, things were back on track with the location of a 12 year old Swan 48 in Connecticut. Originally designed by German Frers in 1994, the boat is actually just a matter of inches under 50ft LOA, which made her the equivalent of an up-dated production version of Denis Doyle's legendary Moonduster. As one of the senior members of the eclectic McGettigan Crew Panel had sailed many successful races with The Doyler on The Duster, it was reckoned that this was all as it was meant to be, as it offered the additional prospect of an immediate season or two in the Caribbean with a boat which was of a size to be still manageable without a professional crew.

This also offered the possibility of racing the Caribbean 600 in February 2013, an attractive idea as the boat came with a formidable wardrobe of sails. But if that aim was to be comfortably fulfilled, the boat had to be ready to sail south to the Caribbean in November, when fleets of boats make the journey south from New England as soon as the hurricane season is over.

However, with Superstorm Sandy wreaking havoc in the New York coastal area in September, it was impossible to bring things to fruition as quickly as hoped. Despite the shared language, buying a boat in the US can be much more difficult than buying one in Europe. And as you finally do close the deal, you are already discovering that boats in America, while seemingly identical to their sister-ships in Europe, can often carry very different equipment.

So the programme slipped, but by late November Alan was doing sea trials on Long Island Sound with a surveyor, and by early December he had been given a favourable report, and negotiations were drawing towards a conclusion through a broker with an owner - never personally met - who lived in another distant American state.

Finally, with the seller faced with the exigencies of the end of the tax year on December 31st, the deal was concluded on that last day of 2012. Meanwhile, back in Ireland over the Christmas/New Year holiday, the crewing arrangements were firmed up between those who were to do the delivery passage in late January/early February from Connecticut to the Caribbean via Bermuda, those who then wished to do the Caribbean 600 Race on February 18th, and those who would cruise the islands afterwards.

It was a very busy time with the new boat, now re-named Wolfhound, being transferred to Irish ownership with details like the IRC rating being re-issued by the ISA. But on 25th January Alan and three long-time shipmates arrived in Connecticut knowing that the weather prospects were bad with Snowstorm Nemo developing over the northeast United States, but equally knowing that a favourable weather window would follow it.

However, they knew there were some days of work to be done in any case before they could sail, and by the time that was completed the economy of Connecticut had benefited from the Wolfhound campaign by a significant amount. As expected, a new top-of-the-range Viking liferaft had to be installed, but less clearly expected was the necessary acquisition of a new Zodiac inflatable tender and outboard, and completely inexplicable was the need to install a new Charger/Inverter, the original having disappeared. The boat, in other words, was not precisely as Alan remembered her from the last time he'd seen her in early December, but with goodwill all round she was made ready for sea.

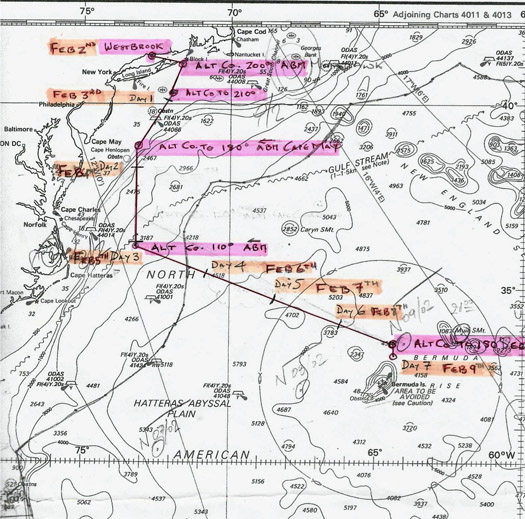

Thanks to friends in the Cruising Club of America, Alan and his crew had a briefing session with people well used to sailing the 650 miles to Bermuda at 1215 on Saturday 2nd February, and at 1530 hrs they headed out round the northeast end of Long Island and shaped their course parallel with the American coast towards Cape May in order to slip between weather systems and get in to more clement conditions as quickly as possible, for though the winds were favourable northerlies and easing after the storm force winds of Nemo, the temperature was minus 8.

Getting through the ice departing from Connecticut on the afternoon of Saturday February 2nd. As darkness drew on, the temperatures plunged. Photo: Alan McGettigan

In such conditions, it was so cold that they motored with only the mainsail set, and put in watches of only half an hour. But progress was good and through Day 2 (Sunday February 3rd), everything was going according to plan, they were finding their weather window, and it was even getting slightly – just very slightly – warmer, as by now the wind was easterly, though as it was 30 knots with some gusts to 50 knots it was by no means the "champagne sailing" they'd been promising themselves once they got down to Cape May.

By Monday morning conditions permitted one hour watches and soon they were sailing properly, but there was concern about a new weather system developing to the eastward in the tail of Storm Nemo. However, satisfactory progress was being maintained and they were able to move up to two hour watches with half hour rotations. The going was good, but that was as good as it was to get. In order to keep up battery power, they tried to put the new Mastervolt Charger/Invertor into service on the remote setting, but the indicator light failed to show. This was serious. They were halfway through the passage to Bermuda, but knew that unless someone aboard suddenly discovered his own previously unrevealed genius as an electrical and electronics engineer, by Day 4 (Tuesday February 5th), all systems except the engine would be down through lack of power – this duly happened at 0350hrs on the Tuesday.

They were now halfway between the American mainland and Bermuda, but with the frequently changing wind by this time from the west, it didn't make sense to try to beat for the Chesapeake as the nearest mainland all-weather port of refuge, even if Bermuda is a place difficult of access. So they pressed on, but later on the Tuesday the engine failed to re-start. It was found that it could be run intermittently, and as it had been serviced before leaving, the suspicion was that grunge in the fuel tank – the boat had been effectively out of commission for more than a year – was causing fuel blockages, so they made do without the motor, as any use would only make the blockage problem worse, and maybe damage the engine.

Their situation was seriously unpleasant, for although cooking had been by gas, the top-of-the-line American marine cooker relied on an electrically-powered safety switch for its ignition. So for the time being they endured cold food – mostly breakfast cereals and fruit – and resisted the temptation to cut the gas line and by-pass the safety connection to the stove, though without heating of any sort and only cold food, the effect on morale was dire.

By now they were getting into very bad weather again with huge seas and rising winds, and on Day 5 (Wednesday February 6th) the furled headsail (it was the Number 4) was simply shredded by the strength of the wind despite being rolled. But conditions had eased enough the following day to get the remains down and cleared from the forestay.

Despite everything, they were getting near Bermuda, for even with their problems they had averaged 5.5 knots from Connecticut. But the weather was once again deteriorating, and now their sense of being cut off from all assistance was exacerbated by the discovery that their hand-held VHF was completely discharged, even though it had been fully charged ashore prior to departure, while their location was too remote for personal mobiles to be of any use.

So near and yet so far.....Wolfhound's route towards Bermuda

So with all systems down, visibility very poor and conditions deteriorating, with the vessel getting a horrendous pounding with a couple of knockdowns and chaotic dislocation below to such a degree that it was safer to remain on deck, the only navigational information available was through a single iPad which was already down to 15% power. But even if they could find their way the final fifty miles to Bermuda, they had no engine power to get through the intricate reefs and St George's Channel.

Throughout all this, Alan recalls that he never heard a voice raised in anger or frustration – he had shipmates to cherish. And that's what he did. He cherished them. Much and all as he'd had great hopes for his new boat, he decided that the risks to life and limb in trying to make the final rock-strewn miles to Bermuda were simply too great. It was a choice of putting his friends' lives at great risk, or abandoning ship. It was no contest. He activated the EPIRB at 1530 hours on Friday February 8th.

The offiial US Coastguard report into the rescue is downloadable below as a PDF document

As the American authorities couldn't immediately trace the registration of the EPIRB (see downloadable PDF of Coastguardnews below) they didn't at first know what they were looking for, but that Friday night, Wolfhound was located in darkness by a US Coastguard C130 Hercules aircraft from Norfolk, Virginia, which dropped emergency supplies and more importantly indicated to them that help was on the way. Meanwhile Bermuda MRCC instructed two ships in the area, the Empire Champion and the Tetien Trader, to alter course towards Wolfhound.

The Empire Champion was unladen, which made manoeuvring in the extreme weather difficult, but the fully-laden Greek ship Tetien Trader arrived at dawn on Saturday February 9th and did the job. Floating deep, she provided an almost rock-like base onto which the crew of Wolfhound, which was alongside with long warps fore and aft, could be hauled aboard by the sheer brute strength of eight men pulling on a heavy warp which the Irish crew had to tie round themselves using a bowline knot.

The chaos of Wolfhound's cockpit seen as she lay briefly alongside Tetien Trader during the rescue. Photo: Alan McGettigan

Throughout all this, in a cruel twist the sky had temporarily cleared and there was even a hint of sunshine before the next wave of bad weather closed in again later in the morning, During the rescue, the yacht was rising and falling fifteen to twenty feet up the steel side of the ship, but after the crew had been hauled to safety, the extreme conditions soon snapped the warps holding Wolfhound alongside, and she drifted away. She was not seen to sink, as some reports have suggested, and might even be still out there, alone on the ocean. Her crew meanwhile headed east across the Atlantic on the Tetien Trader, and were landed at Gibraltar on Wednesday February 20th.

Last glimpse of Wolfhound from Tetien Trader before the weather closed in again. Photo: Alan McGettigan

Journey's end. Tetien Trader in Gibraltar on February 20th. Photo: Alan McGettigan

As for what might be learnt from this sad story, that can be analysed in due course, but all that can be said this morning is that it could have been much worse. No lives were lost, nobody was seriously injured. In extremis, the right and proper priorities were observed. Life can go on. Indeed, it was going on almost immediately. On the Transatlantic passage on the Tetien Trader, Declan Hayes was moved to pen some poetry:

Wolfhound (the adventures of Alan, Morgan, Declan & Tom)

Dublin, Boston, then Bermuda bound

To start our journey on the new Wolfhound

Tortola, Antigua, Azores and home

Cutting through the Atlantic foam

It was oh so very, very cold

As we set out on our journey bold

Dreaming of the warm Gulf Stream

And the Caribbean sun on our beam

But that was never going to be

As we battled wind and heavy seas

All power went and food was low

As we were battered about in the merciless blow

We signalled help by satellite

But no help came until the night

The drone of engines in the sky

Then searchlights allowed them us to spy

By daylight two ships had answered our call

But we could not board due to swell and squall

Persistence paid and one by one

We were hoisted aboard, it was no fun!

Wolfhound crashed against the mighty hull

Then broke her lines with a mighty pull

She drifted past the stern abeam

The end of Alan's epic dream

Aboard the ship, the Tetien Trader

Our lives intact, disappointment faded

A nicer crew you could not have chosen

The captain, cook, not least the bo'sun

Ten days we spent on that good ship

Before they let us off at the Rock of Gib

A trip I doubt we will ever forget

So very different from travelling by jet!

The moral of the story is plain to see

You never know what's going to be

Life is precious and full of hope

A boat's just plastic, metal and rope

Time will pass and memories fade

But the experience is there, forever made

Another part of who you are

Another story for the bar!

Comment on this story?

We'd like to hear from you on any aspect of this blog! Leave a message in the box below or email William Nixon on [email protected]

Irish Yachtsmen Rescued From Stricken Vessel Off Bermuda

#Wolfhound - Four Irish yachtsmen have been rescued from a recently purchased vessel some 70–miles north of Bermuda after it suffered both power and engine failures amid stormy conditions off the northeastern United States.

The 48-foot Swan class sloop Wolfhound, purchased recently by owner/skipper Dalkeyman Alan McGettigan, had departed from Connecticut on 2 February en route to Antigua in the West Indies to compete in the RORC Caribbean 600.

As WM Nixon wrote on Afloat.ie recently, the Wolfhound was expected to eventually call Dun Laoghaire home following its Caribbean adventure.

But according to Bermuda's Bernews website, trouble began when the vessel reportedly suffered a loss of battery power due to the failure of a new inverter charger some 400 miles off the Delaware coast.

This was followed by engine failure a day after departure which left the vessel without communications or navigation systems for eight days.

Between Friday and Saturday the boat reportedly suffered two knockdowns in treacherous weather on the heels of the midwinter storm that recently battered America's northeastern states, and which led McGettigan to activate the on-board emergency beacon.

After a fruitless search by US Coast Guard aircraft, the yachtsmen were eventually located by and transferred to a passing cargo ship, Tetien Trader, which had joined the search effort.

The Wolfhound later sank some 64 miles north of Bermuda.

McGettigan's crew from the Royal Irish Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire have been confirmed by the club's sailing manager Mark McGibney as Declan Hayes and Morgan Crowe.

Tom Mulligan of the National Yacht Club has been named locally as the fourth crew man on board.

A source close to Afloat.ie says that Hayes telephoned home from the Tetien Trader and confirmed he and the others were being "well looked after" by the Greek crew of the cargo vessel, which is due to land in Gibraltar on 19 February.

A member of the RIYC, Alan McGettigan is an experienced offshore skipper, previously sailing in areas as far afield as the Baltic Sea, the Caribbean, the South China Sea and the Mediterranean, and having competed in past Round Ireland and Dun Laoghaire to Dingle (D2D) races, most recently in the yacht Pride of Dalkey Fuji.