Displaying items by tag: UK Sailmakers Ireland

New 'JX' J109 Jib Tested By UK Sailmakers Ireland on Dublin Bay, Bringing New Technology to Irish Sailing

Leading the charge with the design of a new J109 'JX' jib – tested for the first time on Dublin Bay last week – UK Sailmakers are hoping for a return to a 'golden era' for Irish sailmaking.

For many years, Ireland was a hotbed of technology and development for the sailmaking industry. With Hood Sailmakers weaving America's Cup winning cloth in Clonakilty, Ron Holland designing Half Ton Cup winning yachts in Crosshaven, and John and Des McWilliam designing and building championship winning sailing out of their Crosshaven Loft – it was an exciting and golden time in Irish Sailing.

However, in recent years this 'buzz' has all but disappeared writes UK Sailmaker Graham Curran who believes it is time to put the Irish sailor back at the fore of testing and development.

“Irish sailors have always been at the forefront of the sport", says Barry Hayes, Head of Development at UK Sailmakers International and Director of UK Sailmakers Ireland – “It’s about time the sailors in one of the most competitive IRC fleets in the world had something new to play with. Something exciting. To be part of something bigger – and progress the sport.”

Barry Hayes, Head of Development at UK Sailmakers International

Barry Hayes, Head of Development at UK Sailmakers International

Sailmaking is an ever-evolving industry with new materials, designs, systems, and software requiring extensive testing and validation. The waters of Ireland are the perfect proving ground with all variety of conditions and a deep pool of talented sailors to draw from.

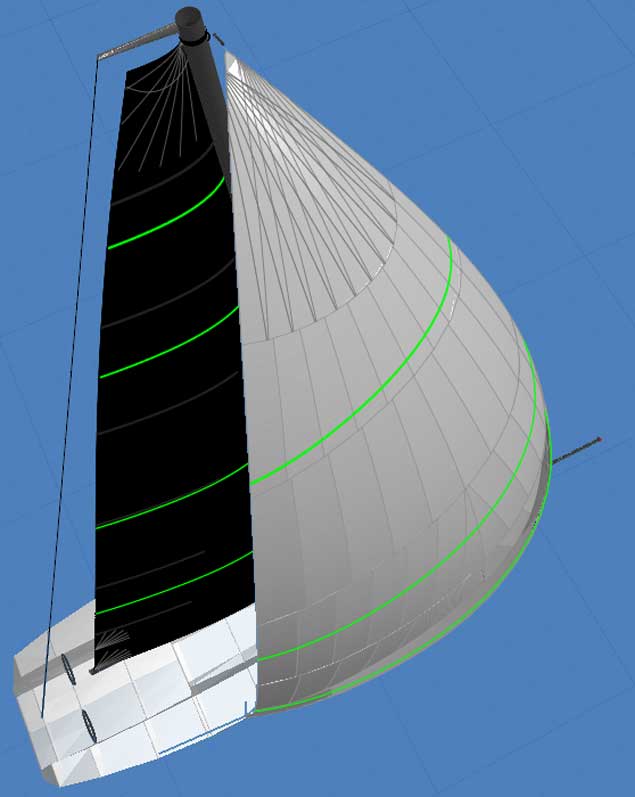

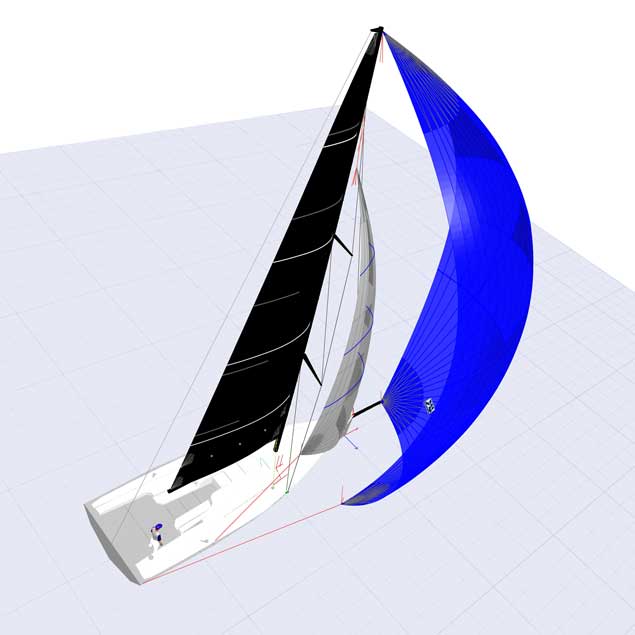

UK Sailmakers International, in conjunction with UK Sailmakers Ireland, have committed significant resources to FSI (fluid-structure interaction) and CFD (computer fluid dynamics) analysis to develop new shapes and moulds for popular modern IRC racing yachts. The initial focus of this development programme is on sail plan improvements for the J109 class in Ireland. The first result of the programme is a new light Jib (JX). The initial results, after an extensive day of testing in Dun Laoghaire, have been very encouraging.

'The initial results, after an extensive day of testing in Dun Laoghaire, have been very encouraging'

Hayes and Curran promise to share the full details and results of the testing in a future article but to whet appetites they describe the Dublin Bay test session below.

Mark Mansfield aboard John Maybury's "Joker II" to leeward with Barry Hayes and Graham Curran aboard the INSS’ “JEDI” pacing close to windward

Mark Mansfield aboard John Maybury's "Joker II" to leeward with Barry Hayes and Graham Curran aboard the INSS’ “JEDI” pacing close to windward

Kenneth Rumball of the Irish National Sailing School was kind enough to allow us the use of JEDI for the afternoon. John Maybury generously provided both his time and Joker II for a perfect day of close quarters two boat testing and tweaking on Dublin Bay.

After a quick sail transfer, both boats lock back in for another round of testing. Joker II using UK Sailmakers JX jib

After a quick sail transfer, both boats lock back in for another round of testing. Joker II using UK Sailmakers JX jib

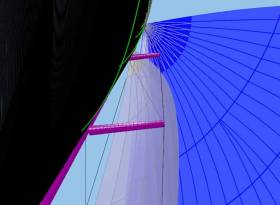

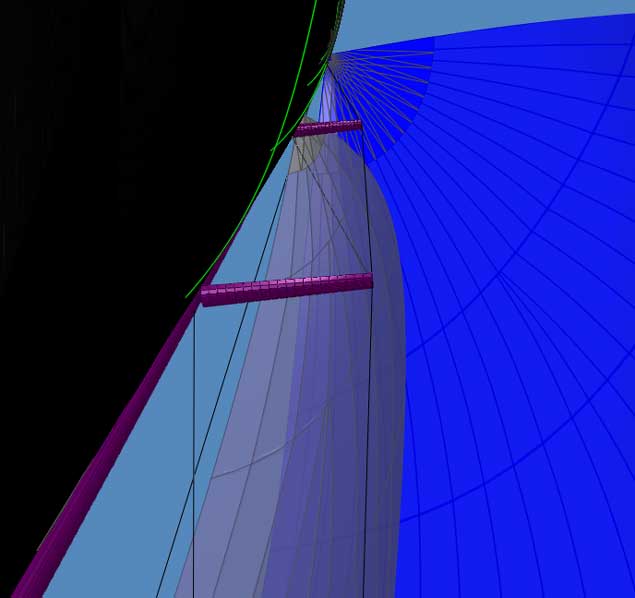

JEDI's Uni-Titanium mainsail complimented nicely by the test JX jib. Computerised FSI testing is a crucial element of modern sailmaking

JEDI's Uni-Titanium mainsail complimented nicely by the test JX jib. Computerised FSI testing is a crucial element of modern sailmaking

Downwind Sails—What Are The Options?

In recent years, asymmetric sails have become much more popular. If you have a boat with a sprit you will likely have 100% asymmetric downwind sails. If you have a boat with a pole, it is likely you will (or should have) at least one asymmetric spinnaker for reaching which will be either tacked to the bow or else tacked to the end of the pole, with the pole set as low as possible.

However, there are other downwind sails that are now becoming much more popular and on competitive offshore boats they are becoming an integral part of a boats arsenal.

Barry Hayes, Sail Designer and Director of UK Sailmakers Ireland has a great deal of experience with these sail options from his time running UK Sails Hong Kong and here, in this article published in association with ICRA, he goes through their use and set up.

The sails in question are: Flying Jibs; Code 0s; Jib Staysails and Spinnaker Staysails

Flying Jibs set on a sprit on a cable outside the forestay, are the new kids on the block

Flying Jibs set on a sprit on a cable outside the forestay, are the new kids on the block

Recent IRC rules changes have revolutionised how modern race boats are sailed; both offshore and inshore. Rule 21.3.3, changed in 2017, now permits your headsail to be flown outside the forestay on a prodder or bowsprit:

21.3.3 RRS 50.3(a) is amended to the extent that a spinnaker or a headsail may be tacked to a bowsprit.

With the major IRC rule change you can now set your headsail outside the forestay. This has changed the game how modern race boats sail offshore and inshore.

Flying Jibs

Flying jibs, set on a sprit on a cable outside the forestay, are the new kids on the block.

Flying Jib

Flying Jib

With the development of code zeros and as boats got faster; race boats needed a smaller, flatter sail to reach faster and higher. Their design and function are totally different from a code zero as we know it.

The sail can be used from 5 to 20 kts, set on a small sprit. From 45 degrees down to 80 degrees so it's really designed for fast reaching. Easy to set and furl. You can leave it up when not in use reaching. The sails can furl in and out as needed. It's always hoisted and dropped on the windward side of the boat. The sail is used with a headsail on the forestay and/or a Jib staysail inside that. So a 2 or 3 headsail option depending on the angle.

The flying jib is sheeted behind the keel at a point which sets the sail evenly along its forestay cable. The force is always pulling the boat forward. The head of the sail set at the same height as the top of the forestay both to reduce drag and righting moment. The area is never greater than the IRC Head Sail Area (HSA). The Flying Jib effectively replaces the need for a High Clew Reacher (or Jib Top) as this option is much more efficient than a Jib Top.

The Anti-Torsion cable which the Flying Jib is flown off is absolutely critical. It has to be of very high quality or there will be problems before you have even started. The furler and its functionality are also crucial for the Flying Jib to perform. A ratchet furling system provides complete control of when the sail opens, and allows you to stop it if you have any drama. It also ensures the sail does not unfurl prematurely during the hoist. You can hoist and tension the cable and be 100% happy before you deploy.

Flying Jib

Flying Jib

Flying Jib

Flying Jib

Needless to say; the design of the Flying Jib is paramount. The twist should be about 12% set at 70 % of the leech to control how the sail opens and closes as the sheet is eased. The draft is set at approximately 38% so the power is forward. The shape is more or less the same as a J2 headsail design – too deep won’t work as you need a good working sail shape.

Code Zero

Code Zero – it is a versatile sail; it can be used for cruising and deliveries – but most of all racing

Code Zero – it is a versatile sail; it can be used for cruising and deliveries – but most of all racing

After considering the above; we now move to the code zero. The must have sail in any offshore boats arsenal.

A Code Zero is a versatile sail; it can be used for cruising and deliveries – but most of all racing. Code Zeros are designed to be used in light airs upwind – reaching in medium wind, and downwind in heavy airs. For cruising and offshore boats a code zero is essential at night and in heavy airs.

The working angles of the sail are 50 degrees to 120 degrees apparent wind angle – and can also be used in heavy airs down wind or at night. If you get a knockdown or broach you just furl it away.

The size is normally Masthead with a 165 % overlap and the mid girth for racing boats needs to be 75 % of the foot length to satisfy IRC rule requirements.

Code Zero

Code Zero

Under 35 foot boats can use direct furling but anything over that you need topdown furling. So the sail is tight on the cable and the load of the furling system is halved. This will increase the furling line speed under load and will give you a tighter furl, which is critical with windage and handling. The sail can be masthead (MHO) or fractional to the top of the forestay (FRO)

Code Zero

Code Zero

Having an MHO with 165% over lap normally works out at double the headsail area. But with the shape of the sail and the 75% midgirth for racing sails. The sail is very powerful with a flat design shape.

Code Zero

Code Zero

With modern designed code zeros the leech never flaps like other designs. The sheeting angle needs to be 45% degrees. Any lower will have an open leech losing power. The foot should be flat upwind but reaching it should be full. To bring the power forward. You can use an MHO with a reef in the main to push the bow down and unload the ruder and reduce the lead of the boat. Increasing the down wind speed.

Code Zero

Code Zero

The sail is always hoisted and dropped on the windward side with one sheet on the sail. If you use a top down furler on the code zero. then you can use that same furler on the Flying Jib without having 2 furlers. You cannot do this with a standard furler without a ratchet.

Code Zero Furler

Code Zero Furler

This now brings us to Jib staysails and Spinnaker staysails. There is a big difference between the two sails. And they are used in two totally different set ups.

Jib Staysails

Jib Staysail – its main use is to direct the flow around the mainsail to fill the slot so the apparent airflow is used to its max

Jib Staysail – its main use is to direct the flow around the mainsail to fill the slot so the apparent airflow is used to its max

The Jib staysail is set on a furler on a staysail halyard. Normally tacked 1/3 of the distance behind the forestay, it needs to be hoisted paralell to the forestay., . . Its working angles are from 55 degrees to 90 degrees and set inside the Jib top and or a Flying Jib . This set up will push the bow down a lot. And you can use this set up with a high stability boat for reaching.

The design of the sail is very flat with medium draft at 40 % and a small amount of twist. As it’s being used in heavier wind, its main use is to direct the flow around the mainsail to fill the slot so the apparent airflow is used to its max. The sail is sheeted onto the top of the coach roof or used on the inhauler depending on which set up you have.

Flying Jib Side

Flying Jib Side

These 3 different downwind sails are generally for reaching , either in Lighter air (Code 0) or in stronger wind (Flying Jib and Jib Staysail). They would normally be set when you cannot get a spinnaker up, maybe because the angle is too tight (code 0) or there is too much wind (flying Jib/Jib Staysail).

If you only occasionally sail offshore, you might decide that none of these downwind sail options are needed. However, if you sail offshore regularly we can all remember times we end up reaching in light to medium airs, too tight for a spinnaker or the spinnaker is too powerful. What do we do? We outboard sheet our Headsail. However with the prevalence nowadays for non overlapping headsails, reaching for long periods with a small Jib is not quick, hence the benefit of these sails. There is a reason why all the top offshore big boats now all have these sails. Just look at the photos of the Volvo, Imoco 60s, Rambler etc to see them all using these type of sails.

Spinnaker Staysails

Staysails are like a mini code zeros; set inside your Symmetric or Asymmetric Spinnaker

Staysails are like a mini code zeros; set inside your Symmetric or Asymmetric Spinnaker

Now on to the Spinnaker Staysail. This sail has evolved a lot from the days of large Jib staysail with a hollow leech. Those days are well behind us. A modern Spinnaker Staysail is normally set 1 m behind the forestay on a very small furler with a soft Kevlar luff so the sail can be furled and stored away easily. It is set with any spinnaker over 8 kts of wind from 90 to 160 degrees apparent wind angle.

Staysail

Staysail

Modern Spinnaker Staysails are like a mini code zeros; set inside your Symmetric or Asymmetric Spinnaker. It turns the airflow around the back of the mainsail in an even flow. The apparent wind angle is increased as it meets the staysail. The mid girth of the spinnaker staysail cannot be greater than 75% of the foot of the sail but its normally around 65 % to both fit the rig and turn the airflow efficiently around the sail and back on to the mainsail,

Staysail

Staysail

The spinnaker staysail is set on sheets at the base of the shrouds about 0.5 m to 1 m. long with strops and eyes on the end. This keeps the leech open and allows the sails to be sheeted on easily with a 45 degree sheet angle. This mini code zero staysail is a great sail for windward leeward as you can leave it plugged in down the hatch with the sheets on and just put a jib halyard on it to hoist.

Staysail

Staysail

The Staysail is normally trimmed by the mastman. The “if in doubt let it out” policy works very well with a Staysail. If the Staysail is over sheeted it moves the apparent wind angle forward – which means the Asymmetric or symmetric Spinnaker believes it is sailing a higher course than it is – which means it needs to be sheeted on harder – which in turn causes additional heel without any increase in power! All this combines to slow the boat down.

Just a few options that should be considered if you race offshore regularly - Thanks for reading, Barry Hayes

Barry Hayes is a sail designer and product development manager and owner of UK Sailmakers Ireland. He is a member of the Board of Directors UK Sailmakers International

Sail Design: Where Are We Now?

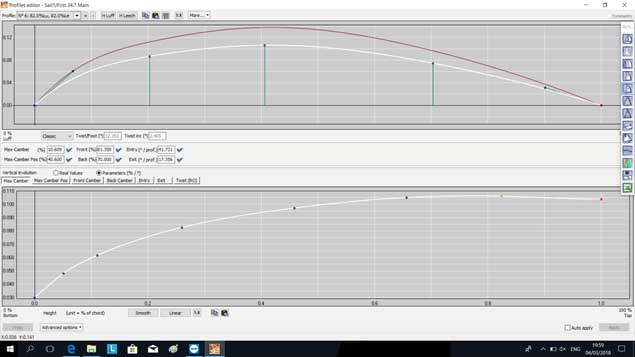

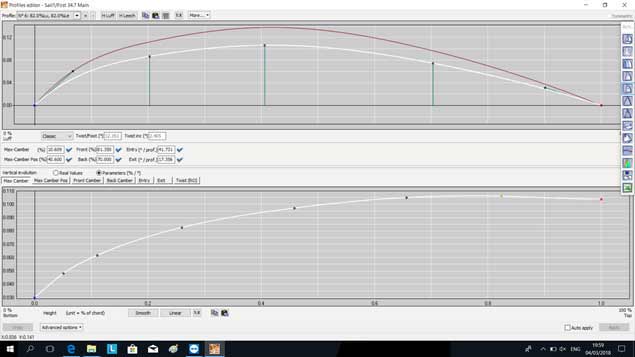

Barry Hayes, owner of UK Sailmakers Ireland, describes new advances in 3D sail design programmes to analyse sail shape and sail design in real time. In this latest article in the UK Series, in association with ICRA, Hayes outlines the Sailpack programme, the preferred tool of UK Sailmakers Ireland.

Once upon a time sail design was akin to a black art. The sailmaker, a whiskery gent with scarred thumbs and a keen eye for a curved line, took a long hard squint at your boat and your rig, weighed up a ton of variables (as a artisan craftsman should), and made a sail that was the compound product of experience and imagination.

Then along came CAD programmes, and the sailmaker quickly came to rely less on intuition and more on proven numbers. There were still hand drawn files, to be sure, but now the designer had the ability to model a sail’s shape and test its performance characteristics on a computer screen, rather than going through time-consuming and expensive wind tunnel testing. Building two full size sails, each one a little different, was no longer necessary in order to test developmental ideas.

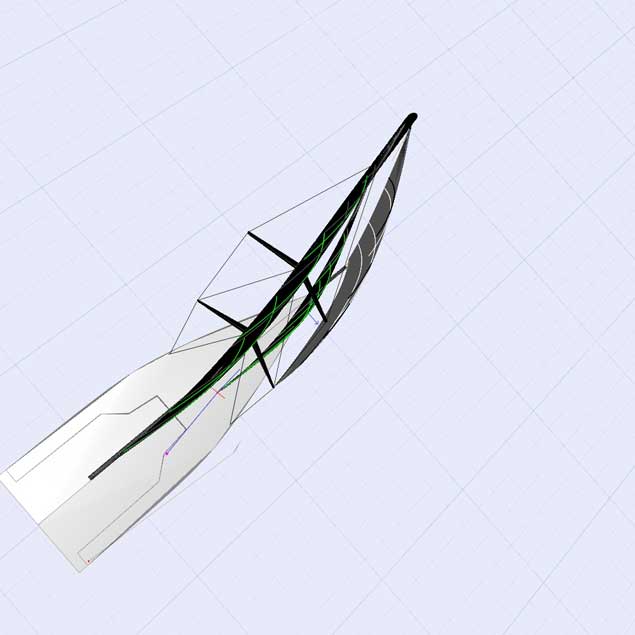

Now say hello to 'Sailpack', the very best sail design programme of all, and the preferred tool of UK Sailmakers Ireland. As the saying goes, “this changes everything.”

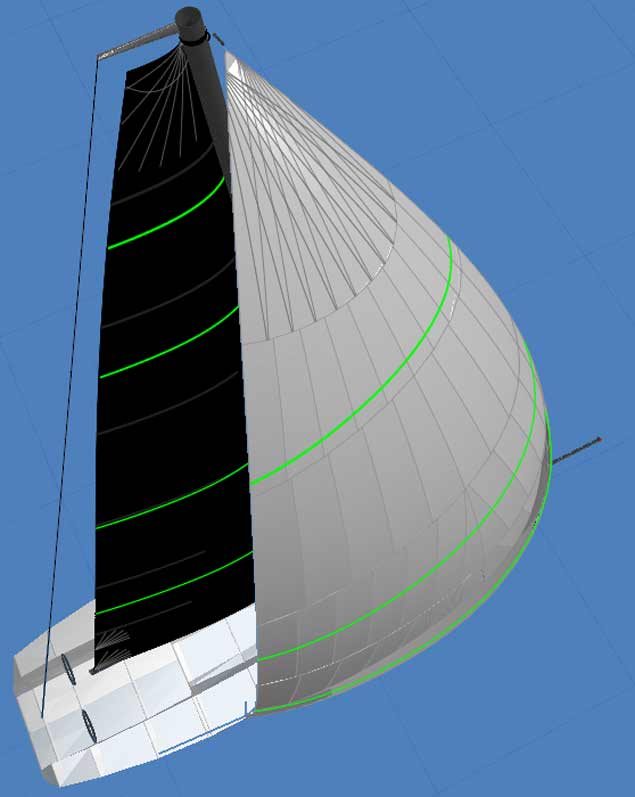

Sailpack comes with a full complement of 3D design and fluid dynamics modelling tools. It not only takes away the nth degree of guesswork from the design process; it allows you, the customer, to see what’s going on in the design process.

With Sailpack, the designer first creates a 3D model of your boat; from this they can then design the sails to perfectly match your boat. This is absolutely the best way to design sails for any boat - you get to see the overall picture of how the sails work together, and how they fit to the boat. You get to see how the sails fit around the spreaders and the shrouds, and you can set the clew height and sheeting angles. Just ask your sail designer to show you these design files, and you’ll see that you’re getting the very best sails for your boat.

Designing bespoke sails

What we are looking for is a sail plan and sail shapes that put the maximum driving force in precisely the right place to produce a perfectly balanced boat – and with the least amount of drag, too.

Into this equation goes the hull, the keel, the rudder and the sails. Added together, this is called ‘the lead.’

Storm Sails

Storm Sails

Here’s an example: Adding extra roach to your main sail adds pressure at the back of the boat, changing the lead and thus causing drag. The extra roach may produce 1% more power, but at the cost of an additional 3% weather helm – not good! To balance this out, you’ll need to add more headsail area and restore the balance on the rudder. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, and the main, jib, keel and rudder all need to perform in concert – which is why we’ll never design a main on its own without looking at the overall picture of the boat.

In the design file below, you can see that the Code 0 is set half way along the sprit, and not at the end. This is to balance the First 34.7 on a reach, and upwind. If it was, indeed, at the end of the pole, it would produce lee helm, and that will affect how the boat sails upwind. It will also reduce the apparent wind angle, allowing you to sail closer to the wind with the maximum amount of power. Going downwind in heavy airs (25 knots at 135˚ apparent wind angle), you may want to move the tack of the Code 0 to the end of the sprit in order to push the bow down.

There are some basic design moulds we work from: one design, cruising, club racing, racing and high-performance racing. Each of these basic moulds has different default parameters and set up including twist, depth and camber position.

Sail camber position A

Sail camber position A

Here’s another example: most mainsails are designed to have the maximum camber between 38% and 46%, and designers don’t go outside these values. You can tweak this parameter to get the driving force forward, but you have to ensure that you do not close the slot between the main and the jib, as that will decrease the airflow across the sails and slow the boat down.

How the design tools work: data points, green lines and mast bend

Designing a sail is very much like designing a wing. The two most important numbers are lift and drag. In the Design Editor file below you can see the selection of tools we have to change the shape of the sail.

Sail Shape B

Sail Shape B

You can see the vertical camber bottom profile, or the horizontal camber top profile. In the top view you can see the overall shape of the sail at each section. This is the section at 82% - the top of the sail at the yellow dot. In the bottom view you can see the parameters are in % values and not real values. With Sailpack you can move any of the data points - the black dots on the screen- up or down to make the sail the correct shape (or you can change the values in the boxes if that’s easier). And then take a look at the green line along the luff and the leech of the sail, which you use to make the entry and exit angles smooth. This is a great tool to assist in getting the shape of the sail absolutely right.

Now let’s add mast bend into the equation. The relationship between mast bend and the slot working together needs to be understood when designing the sail. For sailing upwind with the backstay full on you need the luff curve to allow the sail to flatten (but not over-flatten) the sail so that it retains just enough shape to provide power and driving force without closing the slot - which causes drag. When sailing downwind with the backstay off, the static bend allows the sail to deliver maximum available power which goes straight into the boat’s power train.

Sailing downwind

Sailing downwind

Sails: where are we today?

Mainsails have become a lot flatter in recent years due to the invention of moulded sails technology and the availability of stiffer fabrics. Headsail design has come a long way, too. Jibs and genoas are a great deal flatter in the leech with more twist (between 60% and 80% of the leech), and have become very deep and knuckled, creating a better angle of attack at the entry, which both balances the boat and creates a better flow over the sail.

Overlapping genoas haven’t changed quite so much, apart from the shape of the camber which has become a lot smoother and acquired a straighter exit. 3D design tools mean that we can marry the leech to the rig, which you can see in the design file below - as you can see, the leech is really close the spreaders and shrouds giving the max headsail area and balance between the sails.

Asymmetrical spinnakers have become more user-friendly and easier to use. Higher clews help with the leech twist, and improve sheeting angles. A-sails have evolved from being solely reaching sails to becoming running sails as well, making ‘shifting gears’ even easier. In addition, UK Sailmakers have perfected a bungee retractor system that disappears into the luff and the foot when the sail is hoisted, and eliminates the need to ‘band’ sails – a little bit more environmental friendliness!

Flying Jibs

Flying jibs have become a new asset in the arsenal of any racing boat. They are much faster than a code zero up wind. It allows you to sail higher and with a lot more power. There are a few tips here to making this sail work for you. How the flying jib is set is the most import bit of all. Going back to the days of old; the sail has to be set on a flying forestay at a set height so the sheeting angle and you reduce the drag on the overall sail plan.

Flying Jib

Flying Jib

Flying Jib Top View

Flying Jib Top View

Top-down furling gennakers, with a cable in the luff, are especially good news. This sail is easy to deploy and easy to furl, and will never get a twist in it. It’s a sail that transformed offshore racing and has now trickled down to cruising usage. Whether you are pushing hard in a race, or want to leave a sail up overnight while cruising, the ability to furl/unfurl whenever needed is absolutely invaluable.

Top down cuising gennaker

Top down cuising gennaker

Today’s sails are stiffer than they used to be, and that means that twist has become an even more important design factor. Putting twist into the leech of sails means that, as the wind strength increases, they open up quickly and keep the laminar flow over both sides of the sail working properly. Getting the airflow to stick to the back of your sail is vital. A handy tip here is to put your hand on the back leech/clew area of the sail and feel if the airflow is sticking to the sail.

Modern sails have transformed sailmaking and how sails work. It’s part materials, and part design capabilities. UK Sailmakers use Uni-Carbon to build sails that are stiffer, keep their designed shape, and last longer. The sail is now structurally loaded from head to clew, and Uni-Carbon will also hold the load from luff to leech, making the sail able to hold its shape better. It’s a materials advance that has transformed the art of sailmaking, and allows UK Sailmakers to bring you better, faster, sails that last longer.

Sail Pack Viewer

To use Sailpack viewer, please download this link: http://www.bsgdev.com/CMS3/index.php/menuproducts/sailpack-viewer

and then sign in.

Once you get the key code, you can view the attached design files (downloadable below), which are 3D views of a Beneteau First 34.7

They should give you an idea of sail shape and sail design in real time, including the effects of the principal variables - hull, keel, rudder, sails. From this you can see the relationship between all of the items we have been talking about, and how they work as a team together.

And the best tip of all? Talk to your sail designer!

Barry Hayes is a sail designer and product development manager and owner of UK Sailmakers Ireland and is a member of the Board of Directors UK Sailmakers International

Changing Gears in Different Wind Conditions While Racing

Mark Mansfield, Racing Consultant for UK Sailmakers Ireland, previously wrote about tuning a fractionally rigged mast. In this latest article, in association with ICRA, the four time Olympian describes how to set up the mast and sails for best performance upwind in different wind conditions

BASICS

The first article dealt with getting your mast in a basic good position, centralised sideways, the correct basic rake, the correct shroud tension and finally the correct prebend. This should always be done in medium wind conditions in what we would call the 'base position', normally 11 to 15 knots. It is assumed that once this initial base wind tuning has been done, the sails, when set, fit the mast prebend properly.

By this, I mean when going upwind in say, 12 or 13 knots the mainsail looks to be in a good aerofoil shape (see photo below), with a little bit of backstay tightened. No overbending would be evident (wrinkles running from the mainsail clew to the middle of the mast). Likewise the mainsail in these conditions should not look too full.

It is important to get the mainsail right in these conditions as sometimes the main might just be cut too flat or be just too full and may need a small alteration to the luffround by your sailmaker. When you pull on a lot of backstay in these 12/13 knots conditions, if you still do not get overbend wrinkles, as stated above, the chances are that the main has too much luffround and needs a bit taken out.

On the other hand, if, in 12/13 knots of wind, you get overbend wrinkles immediately you put on a small amount of backstay, it is likely the mainsail is too flat in the luff and will need some luffround added by your sailmaker. These are not very difficult adjustments for a sailmaker and can really make a difference. It is possible to adjust the rigging a bit to help rectify these problems, but really it can often lead then to further issues. So, say your main is looking a bit deep and you ease the lower shrouds to allow the mast to bend forward more, then the mast, in addition to bending further fore and aft also bends sideways to leeward. This, then in slightly stronger winds closes the slot between the main and jib and can be slow.

It is very rare that a mainsail will look fantastic in light, medium and strong wind conditions. As a general rule you design a main, for Irish conditions, to be best in moderate winds and you then either live with it in the other conditions or you adjust the rig to try and get the rig to fit the sail in those light and heavy conditions.

BASE WIND ADJUSTMENTS

All right, let's say the Main does now fit the Mast (either it was right or has been altered by your sailmaker). In these base (11 to 15 knots) winds you are going upwind nicely, with all your crew on the rail and hiking (hopefully hiking hard—really important). What should be evident is your headstay should be moderately tight, maybe a little bit of fall off, your mainsheet should be fairly tight with the top leech telltail streaming most of the time. Your backstay will be tightened a bit and as the wind ranges from say 11 to the 15 knot base range, you will be adjusting your backstay (tighter in the stronger range and less in the lower range). As you tighten backstay, the mainsheet needs to be pulled on more and because this pulls the mast back, it will open the jib leech, so normally the jib needs to be sheeted in more or maybe the jib lead moved forward. As the breeze increases, a telltail sign that you need to tighten backstay is if the helm gets heavy.

Conversely, if the breeze eases and the helm feels a bit dead, then easing the backstay will give you power. But remember, this then will likely require the mainsheet to be eased and the jib sheet eased. I will discuss the importance of the helm feel later.

One adjustment I have not mentioned yet is the main traveller. Up until weather helm becomes excessive, the traveller can be kept in the middle or even to weather. In lighter airs, you can keep the traveller well to weather, and even the boom can be above centerline. My rule of thumb in light air is to have the mainsail clew, (about a foot or two up the leech), in the centre. This may mean the boom is a bit above the centreline but most of the sail is not and that will give you more power and feel on the helm which is very important in light winds. In the higher end of this base (11-15knots) wind range, you may need to leave the traveller down below the centerline to ease weather helm. Try backstay on first though which will tighten the forestay and flatten the sail plan. If this still results in too much helm, then drop the traveller, but only 400 mm or so to leeward of centre. Dropping it too much just closes the slot between the main and jib and leads to a lot of mainsail backwinding which is slow. The reality is if you are overpowered to the level of dropping the traveller further, you really should be on a smaller or flatter Jib. Likely though, in these 11- 15 knot winds you will not be that overpowered.

Below this wind range (less than 10 knots) you are looking for power in order to get all the crew fully on the rail and hiking. Above the base wind range (over 15 knots), you are depowering the boat upwind by flattening and twisting the sails.

The weight on the helm is extremely important. As a general rule, 5 or 6 degrees of weather helm is what you are looking for Photo: Afloat.ie

The weight on the helm is extremely important. As a general rule, 5 or 6 degrees of weather helm is what you are looking for Photo: Afloat.ie

HELM

The helm is the most important indicator of whether the boat is set up correctly or not. It will talk to you, if you listen. Most of my sailing career has been as a helm, Admiral's Cups in the 80’s, one designs in the 90’s (Olympics in Stars, 1720’s, Melges 24's, Mumm 30’s), Commodores Cup etc in the last 10 or 15 years. The weight on the helm is extremely important. As a general rule, 5 or 6 degrees of weather helm is what you are looking for. A bit of weather helm, though it adds drag, is good. The rudder, when it is angled 5 or 6 degrees will give the boat lift. It is not just the keel that gives lift, so does the rudder. If you have neutral helm, chances are you are not pointing that well, and if you have too much helm, chances are you are going slow. If you are wheel steered, put a mark on both sides of central to show what 6 degrees of helm represents. If a tiller, work out also what 6 degrees relates to.

The best mainsheet trimmers, you will find, were also helms. You will see them constantly looking at the helm while they are trimming the main to try and keep the helm in the correct position. If they were helms you will find that they understand what your problems are very early on and will try and address them quickly. It is also very important for a helm to communicate with the mainsheet trimmer what he/she is feeling from the helm.

It is very rare that a mainsail can look fantastic in light, medium and strong wind conditions. As a general rule you design a main, for Irish conditions, to be best in moderate winds and you then either live with it in the other conditions or you adjust the rig to try and get the rig to fit the sail in those light and heavy conditions Photo: Bob Bateman

It is very rare that a mainsail can look fantastic in light, medium and strong wind conditions. As a general rule you design a main, for Irish conditions, to be best in moderate winds and you then either live with it in the other conditions or you adjust the rig to try and get the rig to fit the sail in those light and heavy conditions Photo: Bob Bateman

FORESTAY

Another indicator of whether the boat is set up correctly or not, in addition to the helm, is how the forestay looks. In lighter airs, you want the forestay to have some sag, as this will build power, which will add lift also. As the breeze increases, to say 10 knots or so, tightening the mainsheet will automatically tighten the forestay a little. While all this is happening the backstay will just stay snug. Don’t have the backstay flopping around as this will result in the forestay pumping forwards and backwards in the waves. Until the helm starts to get heavy, it is still good to have some forestay sag. If the forestay tension was set correct initially you will find that as the wind increases from light to medium, the amount of sag in the forestay should decrease just nicely as you initially take on extra mainsheet and then eventually start to take on backstay. As the breeze gets to 14 or 15 knots or so, you generally want the forestay pretty straight as you are now starting to depower a bit. If you are depowering, then a straight forestay means you can point higher.

RIG CHANGES OUTSIDE BASE

All of the above discussion is based on not changing the Standing Rigging (forestay and shrouds) in different wind conditions. For most racing boat owners they will be just happy to get a good base setting and will lock off the shrouds and forestays with rigging pins. In this situation they will be happy with maybe being a little underpowered in the lighter airs and will live with being a bit overpowered in the stronger winds.

However there are good gains to be made in adjusting the rig regularly. Perhaps only 25% or so of boats in Ireland that race at a good level will adjust their rigging for different wind conditions, but you will likely find that most of these will end up towards the top of the fleet.

I normally will have five rig settings:

- 0-7 kts—very light--all crew normally down to leeward—soften and ease rig a lot

- 8-11 kts-transitioning—few crew to weather early and then all – softer than base

- 12-15 kts – Base – (see above)

- 15-20 kts—Depowering a bit. Tighter than Base

- 20 kts and above—Full on powered up, very tight rig

In my next article, I will go through the options to getting to these lighter and heavier rig tensions and what each change of the rig will bring. I will show a chart we have done for a well known one design, the J109, showing what to do in each of these conditions and most importantly will explain, once the shrouds and forestay are adjusted, how to set the sails to maxamise these Rig changes. This chart, though aimed at the J109, will be similar for most cruiser racers.

I will also offer an intermediate option to adjusting all your shrouds and forestay that will be nearly as efficient and will be more easily reproduced. The problem with changing all your shrouds and forestay in each condition is that in very many cases you lose track of what setting you are on. Also, as happens a lot, often someone tightens a bottlescrew when they think the are loosening it which leads to S bends appearing in the mast. Fair Sailing – Mark Mansfield

Article author Mark Mansfield Photo: Afloat.ie

Article author Mark Mansfield Photo: Afloat.ie

In addition to being a self employed sailing Consultant for UK Sailmakers Ireland, Mark Mansfield is a Professional Sailor. He has been competing for 35–years on the International stage including four Olympics in the Star Class, four Admirals Cups in the 80’s, Commodores Cups in the last ten years and numerous other One Design and big boat campaigns. He has a specialisation in rig tuning and has tuned many of the top racing yachts in Ireland. He also is a noted tactician and was tactician on boats which have won their class in the last 3 ICRA nationals, the last three Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regattas (incl overall boat in 2017), IRC Europeans winner, Cowes Week winner, Spi Ouest winner, Cork Week, Scottish Series, UK IRC winner etc. He is a two times Irish Sailor of the Year and a two times Irish Helmsmans Champion. He is available to sail with, coach, tune rigs or advise on rating improvements for any boat, whether they use UK sails or not. Contact Mark at [email protected] or mobile: 087 2506838

Other articles in the UK Sailmakers Ireland/ICRA 'How to...' Series:

Introducing The UK Sailmakers Ireland 'How To' Article Series

Sailmaking Tips & Tricks: Battens, Furling & Caring for Sails

Tuning a Fractional Mast & Rig

Introducing The UK Sailmakers Ireland 'How To' Article Series

It's the end of January. Some of us are still sailing but most of us are sitting around thinking about it. UK Sailmakers Ireland say now is the chance to take advantage of the down time and read something that could potentially improve our sailing experiences in 2018.

In conjunction with the Irish Cruiser Racing Association (ICRA) and Afloat.ie, UK Sailmakers will publish a series of knowledge sharing and 'how-to' articles in preparation for the 2018 season.

From rig tune, to sail trim, to design, materials and development – and perhaps some industry secrets – the aim of the series is to cover a number of wide ranging topics which will appeal to all levels of sailor.

To start off, UK Sailmakers Ireland team member and four time Olympian Mark Mansfield details some on the intricacies of fraction rig tune.

Read the first article on Afloat.ie here

Four Time Olympian Mark Mansfield Joins UK Sailmakers Ireland

The new owners of Cork Harbour based UK Sailmakers Ireland have appointed Mark Mansfield as an agent and racing consultant to their Crosshaven loft.

Mansfield is a Royal Cork Yacht Club stalwart at the top end of sailing for many years — this season serving as tactician on a number of leading Irish keelboat campaigns, including a third consecutive win at the ICRA National Championships on the J109 Joker 2 that also won Boat of the Week at Dun Laoghaire Regatta.

Recently retired from his career in banking, Mansfield has been looking for a new business direction that puts his passion for sailing first.

And he feels that representing the quality product line of UK Sailmakers Ireland is a perfect fit.

“They have always had a strong reputation in Ireland and worldwide for many years and offer a very viable alternative — and with the new owners, will be priced very competitively,” Mansfield says.

He emphasises the quality product and backup, competitive prices and expertise in sail and rig set-ups that will make UK Sailmakers Ireland a new force in sail packages — and the number-one choice for your boat.

When it comes to his own credentials, Mansfield’s renown in the speed arena is in no doubt. A four-time Olympian (in Barcelona, Atlanta, Sydney and Athens) in the Star keelboat, Mansfield also notched a win in the Star Euros and a third place in the Star Worlds. He has also won National and Euro honours in Royal Cork's own 1720 sportsboat class.

In 2005 he returned to big boats, which he had previously helmed in the 1980s to a series of Admiral’s Cups, when he took the helm of the unforgettable Jump Juice in the Commodore’s Cup.

Switching to Sailing Class One in more recent years, Mansfield had found his calling as a title-winning tactician on boats such as Joker 2, Big Picture (Half Tonner) and Anchor Challenge (Quarter Tonner), as well as being a middleman in the Etchells and Dragon class.

He's also produced results offshore winning in class in the 2016 Round Ireland Race.

In these roles, Mansfield has built a solid reputation for his expertise in fast sail shapes and rig tuning. A move into sailmaking is therefore a natural progression — and a shrewd investment for UK Sailmakers Ireland continued growth.

Mansfield will be lending his strategic talents to the marketing of UK Sailmakers’ Titanium package, which has already proven popular internationally. Expect to see more of these on the Irish sailing scene in the coming years, especially with Mansfield involved.

UK Sailmakers Ireland was founded as McWilliam Sailmakers in Crosshaven in 1974 by noted dinghy and offshore racing champion John McWilliam and his wife Diana. Four years later they were joined by John’s brother Des and his wife Sue, who took over the business in 1993.

In 1996 McWilliam Sailmakers joined the Ulmer Kolius group’s network of UK Sailmakers lofts, rebranding as UK/McWilliam. In 2011 Des McWilliam was elected president of UK Sailmakers, succeeding the group’s founder Butch Ulmer.

This past summer Des McWilliam and his wife Sue announced their retirement at the end of this year, as well as the sale of their business to Barry Hayes, who started his sailmaking career with the McWilliam family; Hayes’ wife Claire Morgan; and Graham Curran, who currently works in the Crosshaven loft.

UK Sailmakers Ireland contacts:

Mark Mansfield ([email protected])

Claire Morgan ([email protected])

Graham Curran ([email protected])

Barry Hayes ([email protected])