Displaying items by tag: trawlers

Dublin Bay Sailing Partnership Based on Artistic Endeavour

#iris – It has been said that keeping a boat-owning partnership intact is much more difficult than maintaining a marriage in a healthy state. Thus for most of us with the boat-owning vocation, sole ownership is the only way to go. But for others, in order to defray costs, increase boat size, and maybe leave more personal time free to pursue other interests, the ambitions can best be realised through one of a wide variety of partnerships and syndicates.

These can go through an extensive range, starting at one extreme with what amounts to time-sharing, with the large number of owners meeting (if they meet at all) only once a year for a sort of Annual General Meeting. Other possible setups can mutate through various arrangements where there is considerable overlap between the boat uses by the different owners, right through to the other extreme of total partnership where all owners sail together as often as is possible.

In some cases, the additional social glue of special shared interests is needed to give the partnership that essential extra vitality. There's nothing new in this. W M Nixon takes a look back a hundred years and more to a boat-owning group whose shared interest in art kept a 60ft ketch on a regular cruising programme around Dublin Bay and the nearby coastlines.

The 60ft gaff ketch Iris had a chequered career. She started life at the peak of the Victorian era in the 19th Century as a naval pinnace serving Dublin Bay, and she was presumably driven by steam. At the time, Dun Laoghaire – then known as Kingstown – was becoming the height of fashion as a naval port of call in the summer, made even more so by its convenient access to the centres of power in Dublin, and its strategically useful direct rail connection – pierhead to pierhead – to the main Royal Navy base in Ireland at Cobh on Cork Harbour.

However, as Kingstown had initially been planned solely as a harbour of refuge – an asylum harbor - for ships in distress in onshore gales, with the actual spur to its construction (starting in 1817) being the wrecking of a British troopship with huge loss of life at Seapoint on the south shore of Dublin Bay, the plans had included no provision for convenient alongside berthing for ships.

Indeed, you get the impression that the original underlying thinking was that there should be as little social contact as possible between ships sheltering in the new harbour and any inhabitants of its nearby undeveloped shore. But the rapid if somewhat chaotic growth of the makings of a new harbourside town, plus the advent of more rapid access from Dublin with the coming of the railway in 1834, soon meant that the top brass expected to be able to get off and on their ships in the harbour in style and comfort, and their Lordships of the Admiralty did not stint in providing large pinnaces for them to do so. When these pinnaces were replaced in due course by even more luxurious vessels, those shrewd amateur sailors who could visualise the older boats' potential as re-cycled government surplus found themselves looking at a bargain.

The Iris was originally built with lifeboat-style construction of double-diagonal hardwood planking, which was quite advanced technology for the time. For the can-do boatbuilders of the late 19th Century, converting such totally purpose-built craft into some sort of a yacht was all part of a day's work. Another similarly-built if smaller and different-shaped vessel, Erskine Childers' Vixen on which the Dulcibella of The Riddle of the Sands fame was based, was formerly an RNLI lifeboat with the standard lifeboat canoe stern. She was made more yacht-like by the addition of a staging aft to compensate for the absence of deck space just where you most need it, while underneath this new permanent staging, additional supporting planking was faired into the hull and – hey presto – you've a yacht-like counter stern.

Vixen also had a massive centre-plate complete with its huge casing, and carried more than three tons of internal iron ballast, all of which left little enough space for living aboard during the long and often rough cruise through the Friesian Islands which provided much of the on-the-ground material – and we can mean that in every sense – on which The Riddle was based.

Erskine Childers' Vixen (on which "Dulcibella of The Riddle" was based) in one of his last seasons of ownership in 1899. At first glance, she looks like a typical old-style cruising cutter of her era. But somewhere in there is a classic canoe-sterned RNLI lifeboat hull to which an afterdeck on a counter stern have been fitted as an add-on.

That cruise was in 1897, and shortly after it was completed, Childers went off to serve in the Boer War. This experience left him with doubts about the validity of the British Imperial mission, but equally left him in no doubt that on active service, there were no medals for enduring unnecessary discomfort. So by the time The Riddle of the Sands was published in 1903, Vixen was sold and he'd become a partner in a much more comfortable cruising boat, the yawl Sunbeam, which in turn was followed in 1905 by his very comfortable dreamship Asgard

Meanwhile, with the Iris a fifteen or so years earlier in Dublin, the conversion to a comfortable sailing cruiser was a more straightforward affair, as she'd a more versatile hull shape with a broad stern in the first place, and her new owner was one George Prescott, an innovator bordering on genius. He was an optical and scientific instrument maker, an electrical engineer and inventor, and a state-of-the-art clockmaker.

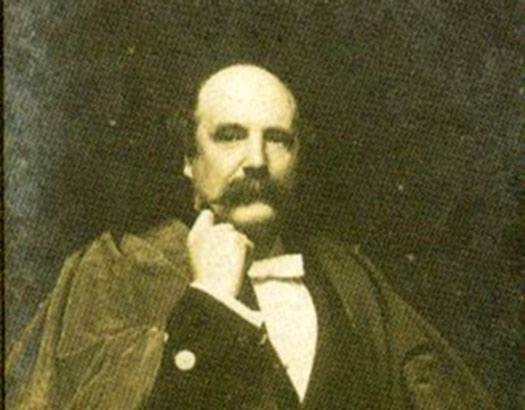

Man of many parts – the polymath George Prescott. Organising the Graphic Cruising Club and running its club-ship Iris was only one of his many interests. He led a long and extraordinarily interesting and varied life, and was nearly a hundred years old at the time of his death in 1942. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

But that was only one part of his life, for he had many friends among Dublin artists, particularly those interested in maritime topics, and he soon found himself to be the secretary of the Graphic Cruisers Club for sailing painters and sketchers, with the Iris becoming the base of their waterborne creative and scientific expeditions on the coast of the greater Dublin area.

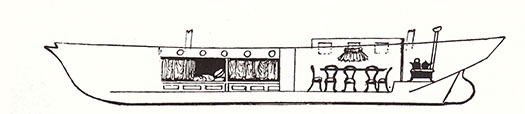

She was ideal for this. She'd been converted for sailing with an orthodox gaff ketch rig, while her roomy hull was internally re-configured to have a galley with a large stove right aft, a huge saloon immediately forward of the galley to be both the clubroom and dining room, and sleeping quarters port and starboard in pilot cutter style forward of that.

Quite a transformation for a former steam-powered naval pinnace. The 60ft ketch Irish in her heyday as the club ship of the Graphic Cruisers Club in the 1890s. She is at her home anchorage off Ringsend, while across the Liffey a couple of Ringsend trawlers are lying in the roadstead known as Halpin's Pool, where the Alexandra Basin is now located. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Accommodation profile of the Iris in her days as the floating HQ of the Graphic Cruisers Club – this sketch by Alexander William first appeared in The Yachtsman magazine in 1894.

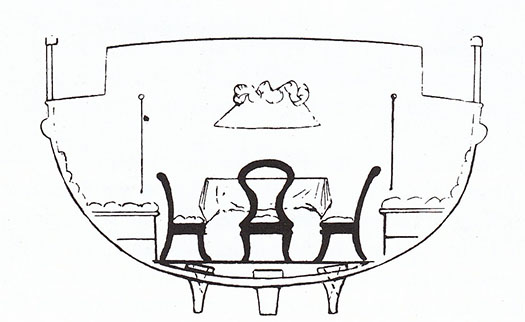

Hull section of the Iris at the saloon, showing the bilge keels which enabled her to dry out comfortably in some some little-known tidal anchorages in the Greater Dublin area.

But underneath the hull, the temptation had been resisted to add a deep keel, and instead the Iris was fitted with substantial bilge keels at the same depth as the shallow keel itself, such that in all she drew only about 3ft 6ins, and would comfortably dry out in a snug berth anywhere that her artistic crew felt they might find subjects worthy of their attention.

Thus she might overnight serenely on the beach at Ireland's Eye or far up the estuary at Rogerstown, and if the Graphic Cruisers Club attention was turned towards County Wicklow, she could comfortably take the ground in Bray or in other little ports inaccessible to orthodox cruising yachts. Yet the claim was that despite the odd arrangements beneath the waterline, she handled remarkably well on all points of sailing, and certainly as she no longer had any sort of engine, she must have sailed neatly enough to get out of some of the confined berths into which her eccentric crew enjoyed putting her.

The Iris in gentle cruising mode off Ireland's Eye as the moon rises – this was sketched by Alexander Williams for The Yachtsman in 1894.

George Prescott seems to have been happy to claim that Iris was a club-owned yacht, but in truth most of his shipmates were impecunious artists of varying talent, so it was his generosity and understated business ability which would have kept the partnership together.

However, it really did seem to function as a partnership, for after the Iris project had been up and running for nearly a decade, he turned his attention in 1896 to building an unusual house on the waterfront on the Pigeonhouse Road in Ringsend, which he happily acknowledged to be the clubhouse of the Graphic Cruisers Club even if he lived in it himself.

Called Sandefjord for some reason which is still unexplained, it looked not unlike a smaller sister of the Coastguard Station next door, complete with a lookout tower. And it's distinctly nautical within, as much of the interior includes fine panelling which came from the wrecked Finnish sailing ship Palme, with the stairs being provided by the old ship's main companionway.

The house called Sandefjord near Poolbeg Y & BC as it is in 2015. When built by George Prescott in 1896, it faced across the Pigeonhouse Road directly onto the waterfront, and overlooked the summer anchorage of the Iris. Photo: W M Nixon

The design style of the Graphic Cruisers Club shore HQ at Sandefjord reflected the lookout tower of the old Coastguard Station next door. Photo: W M Nixon

The house has been restored to become a family home in recent years, and it really is an extraordinary piece of work to come upon on the slip road down to Poolbeg Yacht & Boat Club. Meanwhile, interest in the doings of the Graphic Cruisers Club has been restored by the formidable research talents and tenacity of Cormac Lowth, who single-handedly does more work in uncovering unjustly ignored aspects of Dublin Bay's maritime life in all its variety than you'd get from an entire university department.

I first came across a reference to the Graphic Cruisers Club years ago in an article in an 1894 issue of The Yachtsman magazine, written by Alexander Williams (1846-1930), who was probably the club's most accomplished marine artist. But that was then, this is now, and it has taken Cormac Lowth's dedication in recent times to get the extraordinary setup around George Prescott and Alexander Williams and their friends and shipmates into the proper context.

Alexander Williams RHA was the best-known artist in the Graphic Cruisers Club. A taxidermist of international repute, he was also a noted ornithologist, and his interest in maritime subjects was matched by his enthusiasm for landscape. He was one of the first artists to "discover" Achill Island in the west of Ireland, and in time he created a remarkable garden there in a three years project in which he personally worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the build team.

A classic Alexander Williams portrayal of the trawlers of Ringsend with other shipping in the Liffey. Thanks to research by Cormac Lowth, we are now aware of how the style of the Ringsend sailing trawlers came about through links, between 1818 and the 1914 outbreak of Great War, with the pioneering fishing port of Brixham in Devon, which was the most technologically advanced fishing port in Europe in the mid 1800s. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

They were larger than life, every last one of them, and Prescott and Williams in particular were renaissance men who could turn their hand to any number of creative projects at a time when life around Dublin was fairly buzzing for those with the energy and interest to enjoy it.

And there were links to other aspects of Dublin waterfront life which have a further resonance. Back in January, I'd to give one of the supper talks at the National YC in Dun Laoghaire, and on this occasion the topic was John B Kearney (1879-1967), the Ringsend-born yacht designer and boatbuilder who was the club's Rear Commodore for the last 21 years of his life.

You need some sort of special little link to bring these talks to life, but fortunately I remembered that there's a fine big Alexander Williams painting of sailing trawlers at Ringsend in the NYC's dining room. I didn't know its date as we headed round the bay on the night of the talk, but we struck gold. It was dated 1890.

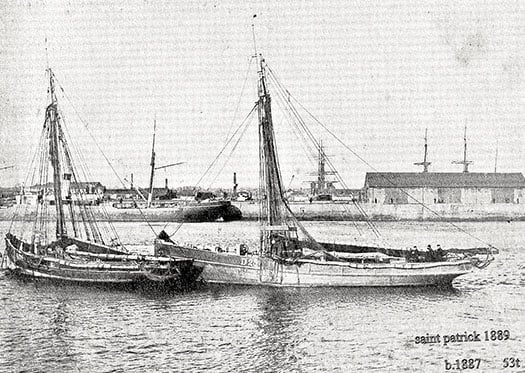

The Brixham style in Ringsend was best exemplified by the largest trawler built in the Dublin port, the St Patrick (right) of 53 tons built in 1887 in the Murphy family's boatyard beside the mouth of the River Dodder. The Murphy family also owned and operated the St Patrick in her fishing, and when John Kearney built his renowned yachts, the earliest (and best) of them were built in a corner of Murphy's Boatyard - the Ainmara in 1912, the Mavis in 1925, and the Sonia in 1929. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Williams was so fond of the Ringsend scene that he lived there for a while in Thorncastle Street where John B Kearney was born, and of course the painter subsequently sailed regularly from the old port in the Iris, and would have over-nighted at Sandefjord too. He is in fact the definitive Ringsend maritime artist, and the picture in the NYC expresses this. And as it includes some of the Ringsend waterfront, we could say that it also includes John B Kearney, for in 1890 the precocious eleven-year-old Ringsend schoolboy was in the boatyards as much as possible, as he had already stated in his quietly stubborn way that his ultimate ambition was to be a yacht designer.

Not a boatbuilder or a shipwright or a harbour engineer, which is nevertheless what he was until he retired in 1944. But upon his leaving the day job - in which he'd been highly respected - he then devoted all his energies to what he had been doing all his life in his spare time. And with his death aged 88 in 1967, his gravestone in Glasnevin cemetery said it all: John Breslin Kearney (formerly of Dublin Port & Docks Board) Yacht Designer.

And if you wonder how on earth we have come to a consideration of John Kearney's memorial stone in an article which purports to be about the social glues which keep boat partnerships in good order, believe me when you get involved with the boys of the Graphic Cruisers Club you never know where it's all going to end.

We've already discovered that in later life Alexander Williams devoted much energy to his garden in Achill while at the same time continuing to be an active member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin. As for George Prescott, he too broadened his already extensive interests, and in his eighties he was much into amateur opera production, even being so deeply involved as to paint the stage scenery himself.

Dublin too was expanding, so he accepted that a move eastward was needed if he was going to be able to continue to commune directly with his beloved sea. So he left Sandefjord, and the final decades of his wonderful life were spent at his new home at The Hermitage on Merrion Strand. Needless to say, Alexander Williams provided him with a painting of The Hermitage which captured the then unspoilt nature of a place you'd scarcely recognize today.

The Hermitage on Merrion Strand, George Prescott's last home as portrayed by Alexander Williams. Courtesy Cormac Lowth