Joe Fitzgerald of Cork went from among us a month and more ago at the age of 94. That month provides us with an added perspective for a full appreciation of his well-lived life afloat and ashore. It enhances our understanding of just how completely land and sea can become happily intertwined in life around Cork Harbour and city.

When that way of life is being lived by someone with Joe’s quiet yet always enthusiastic appreciation of the opportunities for good times in the world of boats and sailing, we find we’re looking at a long life which was a gentle inspiration and encouragement to all who knew him.

He seemed to find the perfect balance between running a demanding yet fulfilling business in the fashionable heart of Cork city, and relaxing through sailing and the company of sailing folk. The family firm in which he succeeded his father was the iconic Fitzgerald menswear, a tailoring and clothing company and shop which Joe elevated to such a reputation for quality in all areas that it’s said the young Louis Copeland, that legend of men’s tailoring, readily travelled from Dublin in order to enhance his skills by working with Joe Fitzgerald, learning from his notable eye for fabric and finish.

All these skills were allied to an astute yet very proper business aptitude. Nevertheless a good week’s work would be celebrated at its conclusion in proper style with a host of such quiet charm that when you found yourself relaxing after business hours in Joe’s company in the heart of Cork city, the sense of being in the midst of true civilisation was central to the mood of the evening, and that mood of generous enjoyment would then be carried on to the weekend’s projects in and around boats and sailing.

Despite his small stature - it’s thought that it was his longtime friend Stanley Roche who first called him “The Tiny Tailor”, though others in Cork will claim it was a northern friend – Joe was a tower of strength around boats, and he first acquired his sailing skills through spending his boyhood summers with an uncle who had a Brixham trawler converted to a sailing cruiser, and based in Crosshaven.

Although during his working years his family home was in Blackrock, Crosshaven remained his sailing home for the rest of his long life, and for his final decade he was a resident of the apartments which had been developed in the former Grand Hotel just across the road from the side door to the Royal Cork Yacht Club, where he was wont to meet his special circle of friends.

This link to shore living in Crosshaven went back to the late 1930s when Joe and some young contemporaries rented a house in the village on a year-round basis. They became much involved with the local dinghy sailing scene through the Cork Harbour Sailing Club, where the inspiration was top international helm Jimmy Payne, who saw to it that the club had a fleet of International 12 sailing dinghies available for charter at 10 shillings for half a day at a time when The Emergency engendered by World War II might have made access to sailing difficult

The International 12s racing at Crosshaven in the 1940s. Photo courtesy RCYC

The International 12s racing at Crosshaven in the 1940s. Photo courtesy RCYC

Soon, a core of useful dinghy sailing experience built up. But by 1943 the waters around neutral Ireland were less directly affected by the war, and the Irish Cruising Club organised a race from Crosshaven around the Fastnet. Lest this seem callous at a time when war was still being waged, it should be noted that several naval and military officers on active service with the Allied forces managed to arrange leave in order to participate.

Among the boats taking part was the famous Gull from Crosshaven, one of the seven participants in the first international Fastnet Race of 1925. Although her legendary skipper Harry Donegan had died in 1940, his son Harry Jnr continued the family ownership of Gull, and for that race of 1943, he included the young Joe Fitzgerald in the crew. As a result, Joe Fitzgerald was elected a member of the Irish Cruising Club in 1944 on the proposal of Harry Donegan Jnr, and today the Fitzgerald ICC membership of 72 years has the air of the eternal record to it.

The Donegan family’s Gull, a veteran of the first international Fastnet Race of 1925, aboard whch Joe Fitzerald qualified for Irish Cruising Club membership in 1944. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

The Donegan family’s Gull, a veteran of the first international Fastnet Race of 1925, aboard whch Joe Fitzerald qualified for Irish Cruising Club membership in 1944. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

Joe Fitzgerald was also busy in 1944 in other ways afloat, as he was continuing to play a key role in the dinghy sailing of the Cork Harbour Sailing Club, and 1944 saw the first races by CHSC in International 12s against Sutton Dinghy Club for “The Book”, the monumental volume in which each year’s racing is recorded by the winning team. It continues today with Sutton DC still in the picture, but it’s the mighty Royal Cork Yacht Club itself which now represents Cork Harbour, and has done so since 1970. Nevertheless it was a surprise for participants in 1988’s event in Crosshaven when Joe Fitzgerald was asked to speak at the dinner, and he gave his typically dry-humoured account of the racing in 1944 all of 44 years previously and waxed enthusiastic about the goodwill which The Book has generated ever since.

The teams racing for “The Book” at Sutton Dinghy Club in 1944. Joe Fitzgerald, on the Cork Harbour SC team, is third from the right of those seated at front. Photo courtesy SDC/RCYC

The teams racing for “The Book” at Sutton Dinghy Club in 1944. Joe Fitzgerald, on the Cork Harbour SC team, is third from the right of those seated at front. Photo courtesy SDC/RCYC

In addition to sailing for sport, Joe Fitzgerald in the 1940s joined the Maritime Inscription, continuing with the voluntary naval reserve which was re-formed as An Slua Muiri after the war. He recalled that his commissioning papers were signed by Eamonn de Valera himself, and his career with the force went on for 39 years. It’s said that he was within weeks of serving for forty years, but the stipulated retirement age was upon him. His many friends and colleagues hoped that the bureaucrats might stretch the rules just a tiny bit to allow him see out the forty years, but the bureaucracy was not for budging. Nevertheless Joe could retire from his many years of service knowing that he had been the youngest Commanding Officer of any region in Ireland.

Meanwhile he had long since been involved in sailing administration, having become Honorary Secretary of Cork Harbour Sailing Club in 1946 while also being an active member of the Royal Munster YC in Crosshaven. There was change in the air, and very suddenly in the late 1940s the International 12s, the backbone of Irish dinghy sailing for many years, found themselves being rapidly displaced by new boats such as the Fireflies and IDRA 14s in Dublin Bay, and the IDRA 14s and National 18s in Cork Harbour.

Joe opted for a George Bushe-built IDRA 14, and soon showed his mettle by winning the IDRA 14 Nationals at Dunmore East in 1951 in his new Mystery, crewed by Michael Donnelly. He was also crewing increasingly on larger craft, both for offshore racing and cruising. But when his father died suddenly at the age of 49 of a heart attack he had to re-direct energies into the family business.

It was a salutary lesson for him, as thereafter, while he was undoubtedly enjoying the good life with a high level of conviviality with a special coterie of close friends, he was way ahead of his time in keeping himself fit. His health regime - which he continued to the end of his days - included a cycling machine in a spare room in the house, and a programme of exercises which saw regular press-ups until well into his nineties.

Yet with a family on the way with his wife Maddie, he seemed the ordinary unfussed successful Cork businessman with a taste for sport and particularly sailing. In the 1960s, in addition to sailing on larger boats with top skippers such as Denis Doyle and Tom Crosbie, he got involved with the lively International Dragon Class which was growing at Crosshaven.

Almost all the boats in it were classic Scandinavian-built Dragons, but Joe decided he’d have his one built at Denis Doyle’s Crosshaven boatyard by the hugely-skilled George Bushe, who had already built his winning IDRA 14 Mystery.

George Bushe made a very good job of building the new Dragon class Melisande. In fact, he made too good a job of it. When the official measurer arrived over in Ireland to approve Melisande, he pointed out that as the Dragon was conceived as a basic economical boat, the frames were meant to have a simple rectangular section. Yet George in his love of providing a good finish had rounded off the exposed edges of the frames. The measurer was not for turning. Melisande would not be recognised as a true Dragon until the fancy rounded frames were replaced by crude hard-sectioned timbers. It was done. But it took a long time to obliterate the memory of having to do so.

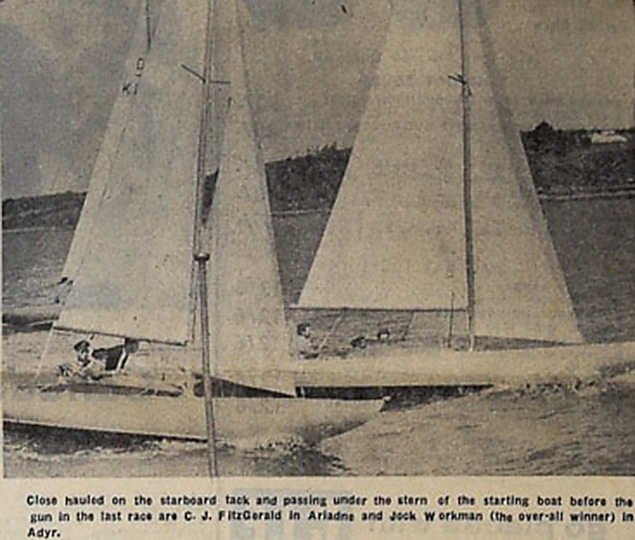

Yet Joe’s time was successful in the Dragons, and he well-represented the Cork fleet in a major international event hosted at Crosshaven in 1962, coming third against the likes of winner Jock Workman from Belfast Lough and runner-up J L F Crean from the Solent.

A photo from the Cork Evening Echo in 1962. The International Dragon Series at Crosshaven, with Joe Fitzgerald sailing for Cork Harbour (foreground) getting the better of eventual overall winner Jock Workman of Belfast Lough at the start

A photo from the Cork Evening Echo in 1962. The International Dragon Series at Crosshaven, with Joe Fitzgerald sailing for Cork Harbour (foreground) getting the better of eventual overall winner Jock Workman of Belfast Lough at the start

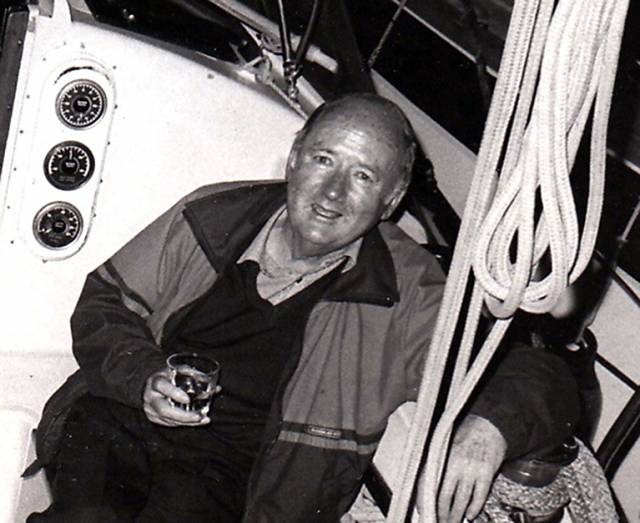

At the 1962 Dragon Open Series are skipper Joe Fitzgerald (left) with his crew of P J Kavanagh and Mick Sullivan

At the 1962 Dragon Open Series are skipper Joe Fitzgerald (left) with his crew of P J Kavanagh and Mick Sullivan

But increasingly he found most pleasure in cruiser-racers, and he teamed up with longtime friend Peter Cagney to order a new Cuthbertson & Cassian-designed Trapper 28, finished on a bare glassfibre hull by George Bushe at his new yard at Rochestown. It was now that Joe Fitzgerald really began to spread his wings, and every possible free moment was used for cruising, though their explorations were not without the occasional mishap.

Approaching Courtmacsherry long before it was a popular port of call, Peter was below and Joe was at the helm when they lightly clipped a rock. In response to the roar from below, the helmsman blithely replied: “Your half of the boat has just struck a rock, but it’s nothing serious……”

Building on experience over the years with his own boats and the larger vessels of friends, Joe Fitzgerald developed an entire philosophy of cruising in which he built up a complete matrix of friendly ports mostly on the Cork coast but also further afield and internationally too, and as well he showed how a place like Cork Harbour meant you could have a cruising weekend of some sort virtually regardless of what the weather might throw at you. And of course, if good conditions arrived, it was amazing what he could achieve by adding a day or two on to the beginning or the end of a favourable weekend.

To do this he maintained understanding friendships which provided lifelong bonds, and if other Cork sailors took to calling them “Dad’s Army”, Joe and his friends in turn showed a level of continuing love of boats and sailing which were inspirational to all. With such an approach, it was only natural that Joe Fitzgerald should be called upon to fill important roles in sailing administration, and while he could have his own way of doing things which was not always the way of other people, the very fact of his many sailing and cruising achievements often gave him carte blanche to continue the Fitzgerald administrative style, while his speeches at formal gatherings were gems to be treasured.

Thus having started at Honorary Secretary of Cork Harbour Sailing Club in 1946, he rose through many ranks, becoming Rear Commodore of the Royal Munster YC as long ago as 1949, and then when the Royal Munster and the Royal Cork merged during the late 1960s, the Royal Cork Quadrimillenial Celebrations of 1970 saw Joe in the key role of the still-extant position of Commodore which gave due recognition to the Royal Munster’s input, and then in 1975 he was RCYC Vice Admiral in support of George Kenefick as Admiral.

But it was in the Irish Cruising Club that the light-touch Fitzgerald management style proved most congenial. For many years he was on the Committee, by 1982 he was Vice Commodore, and he was then elected Commodore by acclamation from 1984 to 1986, heading the club with his calming presence at a time of rapid development.

Meanwhile his boat sizes had gently increased, and they reflected the reality of the needs of a sailor who continued in and around his boats afloat on a virtually year round basis. He moved up to a Moody 33 from the Trapper 28, and he was with that Moody 33 when we happened to drop into Youghal of a Saturday night in 1986 on our way to Cork Week in a 30-footer, and there was the Commodore ICC in fine form for a bit of a party, which duly took place.

By 1990 he’d moved on to a Moody Eclipse with its useful deckhouse, and we found ourselves in our little boat in Crosshaven waiting out a Sunday of filthy weather before better weather settled in to carry us south to Biscay. So Joe suggested that as he’d the deckhouse, we should go and spend the day with him on his boat over in East Ferry, and thus the bad weather was let go through without any interruption to the merriment, and next day we went on our way with a fair wind and sunshine, sustained by the entertaining memories of our thoughtful and imaginative clubmate back in Cork.

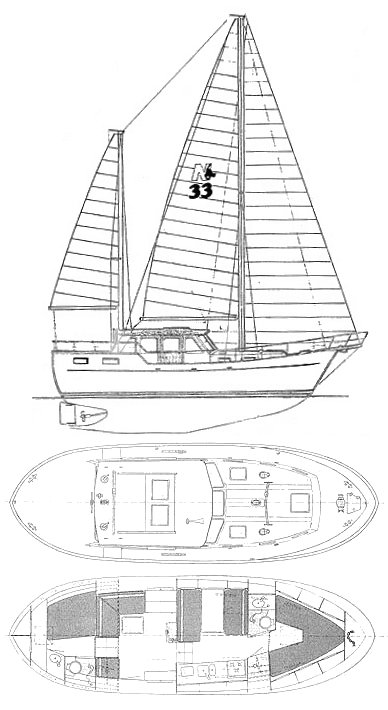

That’s the way it was with Joe Fitzgerald. He made the best of the hand that life dealt him. A widower since 1983, he still had 33 years to live, and he lived them with quiet enjoyment. He even decided he’d outgrown the Moody Eclipse, and bought himself a hefty Nauticat 33 which took on the Fitzgerald name of Mandalay, and provided an “all indoors” boat which enabled this most gallant senior sailor to continue his love affair with boats and the sea and boat people.

The “All Indoors” boat. The Nauticat 33 enabled Joe Fitzgerald to continue cruising until he’d become a very senior sailor.It is impossible to do full justice to Joe Fitzgerald in ordinary words. The world has been a much more interesting place for his having been in it. His view of life was unique. And his view of death was unusual. For his funeral service, he requested no more than a simple humanist ceremony. Yet we’re told one of the speakers with fond memories was a good old friend who was a former chaplain to the Naval Service at Haulbowline. In his quiet way, Joe Fitzgerald was beyond mere imagination, and he leaves family and friends with many cherished memories.

The “All Indoors” boat. The Nauticat 33 enabled Joe Fitzgerald to continue cruising until he’d become a very senior sailor.It is impossible to do full justice to Joe Fitzgerald in ordinary words. The world has been a much more interesting place for his having been in it. His view of life was unique. And his view of death was unusual. For his funeral service, he requested no more than a simple humanist ceremony. Yet we’re told one of the speakers with fond memories was a good old friend who was a former chaplain to the Naval Service at Haulbowline. In his quiet way, Joe Fitzgerald was beyond mere imagination, and he leaves family and friends with many cherished memories.

WMN