On America’s East Coast around Cape Cod, there’s plenty of sea. But as the locals say, it tends to be thin – sometimes very thin - in the places where you might want to go sailing writes W M Nixon.

So in the days when most sailing was being done by working fishermen, they developed commercially viable boats which were wide and shallow, with pivoting centreboards which were able to pop up unimpeded into their casings when ordinary thin water suddenly became very thin water indeed.

But as the rudder might be at an angle when this occurred, it was a mistake to have a second pivoting plate in it, as the “rudder centreplate” might become bent and jammed. So the lower edge of the rudder had to be absolutely in line with the bottom of the exceptionally wide hull. Thus, in order to be effective, the rudder – very shallow in depth – had to be as wide as a barn door, such that in the more extreme cases, it was as much as a sixth of the waterline length.

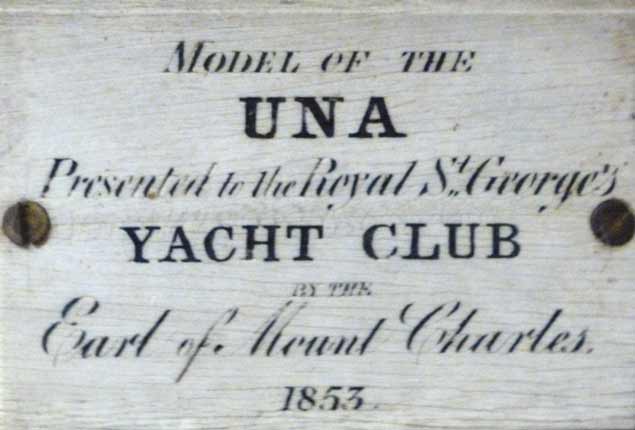

The model of the Una of 1852 in the Royal St George YC

The model of the Una of 1852 in the Royal St George YC

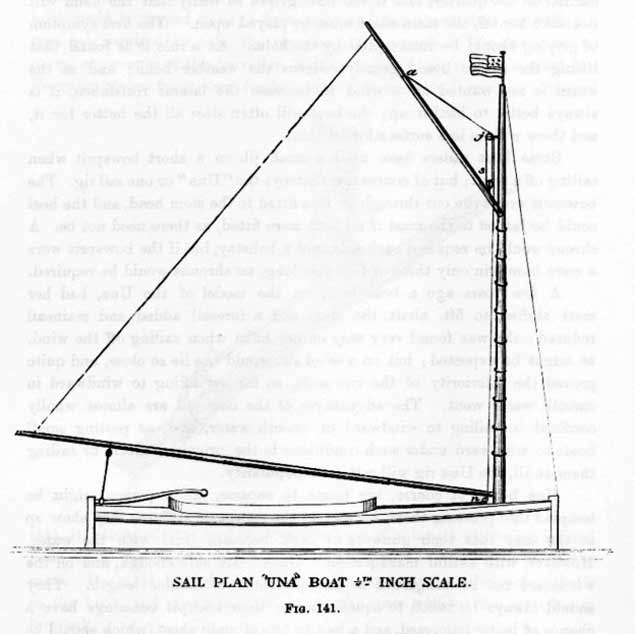

The plans of Una from Dixon Kemp show cat boats at an early stage of development

The plans of Una from Dixon Kemp show cat boats at an early stage of development

These being working boats which sailed mostly in smooth water, normal rules of concentrating weight amidships to optimize performance in a lumpy seaway didn’t apply. In order to maximize the productive area amidships, the masts were moved further and further forward, until in due course, headsails were done away with altogether, and the cat boat was born, with the mast right in the eyes of the ship.

They were a very distinctive type, and as recreational sailing developed in America – the New York Yacht Club was founded in 1844 – inevitably some amateur sailors developed refined versions of the fishermen’s catboat, and they became something of a cult.

In 1852, a wealthy American-by-adoption amateur sailor of Scottish origins, William Buller Duncan, was so taken up with this enthusiasm that he sent a cat boat to a sailing friend in London, the Earl of Mount Charles, whose father happened to be the Marquis of Conyngham, the Commodore of the Royal St George Yacht Club on Dublin Bay.

Despite the donation of the model to the club, Cat Boats never caught on in Ireland – until now

Despite the donation of the model to the club, Cat Boats never caught on in Ireland – until now

The novel cat boat – Una she was called – was so effective in racing in the Serpentine in London that her owner presented a model to his father’s club, and that model – donated in 1853 – is still on display in the RStGYC. It’s possible that Mount Charles hoped to encourage a Una-rigged or Cat Boat class in what was then Kingstown, but meanwhile in 1854 Una made her debut in Cowes, and for a while the type was all the rage among the bright young men on the Solent, but then fashions moved on to something else.

However, back in America, the popularity of catboats grew, and they have had a devoted following ever since, with boats of all sizes developed to the concept. Some are enormous, while others are remarkably short in overall length, for as the rule of thumb is that the beam should be half of the waterline length (you have to see it to believe it), a 14ft catboat was still quite a substantial craft.

The build crew with Judith Malcolm. Emeline – for whom the new boat is named – is second-left.

The build crew with Judith Malcolm. Emeline – for whom the new boat is named – is second-left.

It was in 1920 that the Beetle family of boatbuilders in Massachusetts produced a standardized cat boat, just 12ft 4ins in overall length. But with a beam of 6ft, you got a lot of boat for your money. The Beetle Cat became all the rage, and something like 4,000 have now been built. But as it’s only a genuine Beetle Cat if built on the company’s own mould, often what’s loosely called a Beetle Cat is something else, in the same way that not all vacuum cleaners are Hoovers.

This presents a problem when you want something like a Beetle Cat, but with mods such as in-cockpit seating and other extras. So after Judith Malcolm of Howth had been enchanted with her first sail in a Beetle Cat at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, but had almost immediately come up with all sorts of ideas of extras to make it more user-friendly for use at her home port, she and her husband Ian then contacted Mike Newmeyer at Skol ar Mor in Brittany.

They wanted to see about having a new small cat built, utilizing the school’s boat-building course for optimum value, but built to a design that would make it a Howth Cat rather than anything else.

Ian had already had the Howth 17 Orla built at the school, but constructing the new cat fitted into a much more compact timescale. In fact, with work beginning in September 2017, Judith was told she’d have to take the completed boat away at the end of January 2018.

Despite the non-installation of the battens Finn Goggin’s sail set a treat

Despite the non-installation of the battens Finn Goggin’s sail set a treat

Using the ferry to France and driving a total of 1200 kilometres at the end of January is not everyone’s idea of a holiday when much of Europe is being winter-battered, but fellow woodenboat fans Cathy MacAleavey and Con Murphy were game to provide a support vehicle, and the job was done with enough time to name the boat Emmeline in honour of one of the build team, and have a brief test sail which fulfilled all expectations, including the numbers which can be carried on board.

That said, things were so rushed that they sent up the new sail made by Finn Goggin in Howth without the battens installed. But somehow Finn with her special skills has managed to make the sail so well that the leech stood up in a sweet curve without batten support. Now the boat is safely home – inevitably painted in that distinctive Skol ar Mor shade of green – and there’ll be a more leisurely test sail, all in good time.

Despite the restrictions of the cockpit, the new Emmeline can comfortably carry as many people as your average 12-footer

Despite the restrictions of the cockpit, the new Emmeline can comfortably carry as many people as your average 12-footer

Meanwhile, if you don’t believe any of this, the model of Una is for real. It’s in the basement corridor in the RStGYC, tangible evidence of the previous Irish catboat craze 175 years ago. It’s all a very likeable concept, and so simple. Maybe that’s why they faded from popularity in the 1850s. In sailing a catboat, most of the folk on board have very little to do. We can’t have that sort of thing at all. The devil soon finds work for idle hands. A busy ship is a happy ship…..

Emmeline safely arrived in Howth. Photo: W M Nixon

Emmeline safely arrived in Howth. Photo: W M Nixon