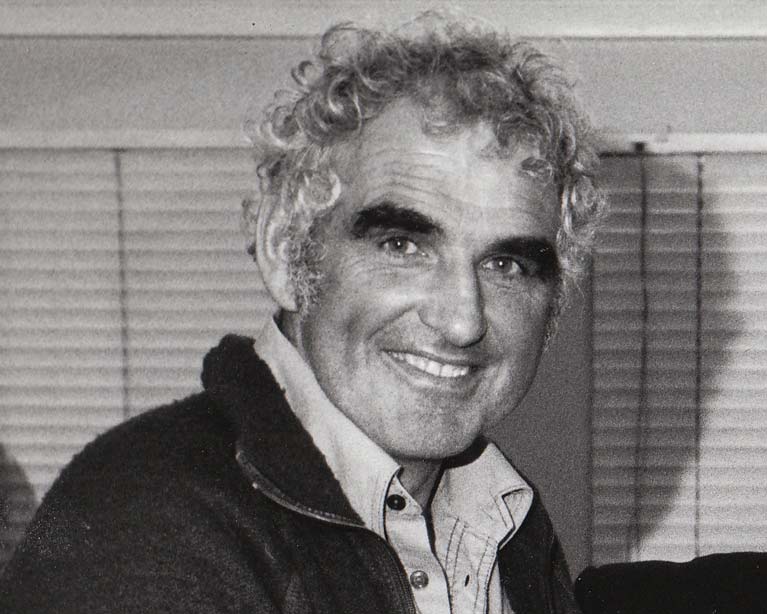

The death of Roy Dickson of Sutton and Howth at the age of 87 takes from among us one of the most multi-talented people in sailing, a man whose 75-year career of innovation and success afloat had started as a teenager with an International Snipe class dinghy at the now-defunct Kilbarrack SC on the sheltered waters inside Dublin Bay’s Bull Island in the 1940s. It was a sailing life well-lived which only concluded in his mid-80s with a little Corby 25, the last Rosie, which he’d modified himself to accommodate the infirmities of old age so that he could continue to pursue a sport which was his life-long passion.

In recent years he will have been thought of the doyen of boat building and modification through the use of modern materials. But as a celebratory lunch organised for him by his many shipmates past and present, inshore and offshore, in Howth Yacht Club in 2015 reminded us, in his astonishingly long career he did his duty and more by wood before bringing in various modern and more exotic materials.

Roy Dickson’s first boat in the late 1940s was an American-designed Snipe, which he raced from Kilbarrack SC

Roy Dickson’s first boat in the late 1940s was an American-designed Snipe, which he raced from Kilbarrack SC Although its “premises” were crowded into a limited space between road and shore, the now-defunct Kilbarrack SC on the north shore of Dublin Bay was an ideal sailing nursery on the tidal but sheltered waters inside the Bull Island. It is seen here in its glory days as a stronghold of the Heron class. Photo: W N Stokes

Although its “premises” were crowded into a limited space between road and shore, the now-defunct Kilbarrack SC on the north shore of Dublin Bay was an ideal sailing nursery on the tidal but sheltered waters inside the Bull Island. It is seen here in its glory days as a stronghold of the Heron class. Photo: W N Stokes

In fact, Roy Dickson was in his prime in exactly the right era, when the Do-It-Yourself boatbuilding movement was at its peak. But among DIY types, he was very quickly into a league of his own, moving almost immediately to a standard which surpassed that of many professionals, so much so that as his interests in sailing broadened to include complex offshore racers, the design and build professionals treated him as one of their own, while on the water other sailors regarded him as the tops.

Yet he managed all this while running the family business in motor parts (which added an engineering outlook to his many skills), and raising a family in Sutton in a lifestyle which reflected the close presence of the sea, which was at its most sheltered along the shore at Kilbarrack. Those early ventures afloat with a Snipe called Bambi at Kilbarrack began before the little club’s sailing waters inside the Bull Island were divided and made prone to silting by the construction of the fixed causeway across to the middle of the island.

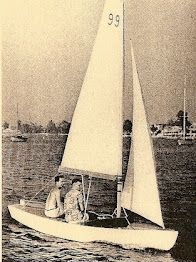

Roy Dickson built and raced two Jack Holt-designed Hornets, complete with sliding seats in the style of the International Canoe Class

Roy Dickson built and raced two Jack Holt-designed Hornets, complete with sliding seats in the style of the International Canoe Class

Until that happened, KSC had a wonderful sheltered sailing area towards high water, when they'd a huge saltwater lake all the way to the Wooden Bridge. Thus they could get sailing even when conditions in Dublin Bay ruled out sailing at Sutton Dinghy Club itself. But soon enough, the young Roy Dickson had himself moved to Sutton, where he was Commodore in 1954 at the age of 22 and already winning international events, and he'd changed boats. He built himself two Jack Holt-designed 16ft Yachting World Hornets – complete with International Canoe-style sliding seats for the crew - between 1954 and 1959, and racing them with success.

But as the best racing in Sutton was in the IDRA 14s, he built himself one of them – Kon Tiki - in 1960, and then in 1961 he and Bunny Conn were in the forefront of the introduction of the Enterprise class, so that was his next command.

Sutton Dinghy Club – Roy Dickson was Commodore here in 1954 at the age of 22.

Sutton Dinghy Club – Roy Dickson was Commodore here in 1954 at the age of 22.

The debut: Roy Dickson sails his new Fireball – the first in all Ireland – across to Dun Laoghaire from Sutton in September 1962

The debut: Roy Dickson sails his new Fireball – the first in all Ireland – across to Dun Laoghaire from Sutton in September 1962 Roy Dickson and fellow Sutton sailor David Lovegrove in a Fireball

Roy Dickson and fellow Sutton sailor David Lovegrove in a Fireball

However, it wasn't until 1962 that all the Dickson stars came into alignment – the International Fireball appeared. He was in there from the start – his first Fireball was No 38 – and with the class's flexible measurement system, the Dickson imperative for innovation had free range. And what he did was noticed by others. It's said that in his dozen or so years with the Fireballs, if some modification he made to his boat of the day proved beneficial, it would be done on every boat in Ireland within a week, and on every competitive boat in the world within a month. And in spreading the news, Roy was always generous with his expertise and assistance.

Former Irish sailing President David Lovegrove – regularly both a crewman or a competitors - particularly remembers how Roy’s home workshop was always open to anyone who shared his level of enthusiasm, and the man himself would willingly work late into the night to ensure that some item of broken gear – whether it was his own or an opponent’s – was ready for the next day’s racing.

As for Roy's sailing, he was competitive right up to world level, doing an early Fireball worlds in America with success with a youthful David Lovegrove on the wire, with another Worlds in the Lebanon – God be with the days when you'd think of having a world sailing championship there – seeing one Bob Fisher as Roy's wireman.

Roy Dickson has won many sailing trophies at home and abroad, and one which has survived down the years is for third in the Fireball Worlds 1967. Photo: Brian Turvey

Roy Dickson has won many sailing trophies at home and abroad, and one which has survived down the years is for third in the Fireball Worlds 1967. Photo: Brian Turvey Roy Dickson at the National Yacht Club in 1984, winner of the Irish Half Ton Championship.

Roy Dickson at the National Yacht Club in 1984, winner of the Irish Half Ton Championship.

Eventually, the Dickson campaigning moved into offshore racing and a Howth base (he had joined HYC in 1974), with a succession of boats which, when combined with the possibilities provided by a variety of measurement rules, provided the artist with an enormous canvas to work with, and he was busy for decades.

He started offshore with an S&S 30, but then bought a new Beneteau First Half Tonner as one of a group purchase with other HYC members in 1980. After the first year, Roy’s boat became different, as he fitted a fractional rig and extended the stern with a sugar scoop, moving steadily to the top of the performance table and winning the Irish Half Ton Championship at the National YC in 1984.

Roy Dickson’s newly-acquired Holland 39ft Imp at the start of the 1987 Fastnet Race, in which he won the Philip Whitehead Cup. He was racing with experimental sails, but soon moved to establish a close relationship with McWilliam Sailmakers.

Roy Dickson’s newly-acquired Holland 39ft Imp at the start of the 1987 Fastnet Race, in which he won the Philip Whitehead Cup. He was racing with experimental sails, but soon moved to establish a close relationship with McWilliam Sailmakers. Top talent – Roy Dickson in the early days on Imp with Peter Wilson, one of many front-line sailors who were keen to sail on the Dickson boats.

Top talent – Roy Dickson in the early days on Imp with Peter Wilson, one of many front-line sailors who were keen to sail on the Dickson boats.

Having exhausted all the possibilities of Half Tonner modification, he then took on the legendary Ron Holland 39-footer Imp, and with her he won the Philip Whitehead Cup in the 1987 Fastnet Race. His sailing enthusiasm was if anything greater than ever, but by his mid-50s he was increasingly troubled by arthritis, particularly of the knees. Yet he gave himself another three decades of active sailing by fitting his boats with wheel steering (his own design and installation, of course) which – as he drily observed – was for him an improvement on a tiller, in that it gave him much more room to move around the aft end of the cockpit, and was also something very useful to hang onto in extreme conditions.

Imp was the first of his boats to get this modification, and there were other interim craft, but his years of maturity became the Dickson-Corby era. He had become intrigued by the highly individual designs of John Corby of Cowes, and in due course he completed the Corby 40 Cracklin Rosie. Her hull had been built in Cowes by Mark Downer, who so enjoyed the Dickson approach that he crewed with him on Cracklin’ Rosie in major events – when success was frequent - whenever possible.

The Corby 40 Cracklin’ Rosie, probably Roy Dickson’s most famous boat.

The Corby 40 Cracklin’ Rosie, probably Roy Dickson’s most famous boat. Cracklin’ Rosie with a mostly Howth-Sutton crew shortly after the start of the 1997 Fastnet Race: A boat, a skipper and a crew at the height of their powers, with regular success at home and abroad. Photo: W M Nixon

Cracklin’ Rosie with a mostly Howth-Sutton crew shortly after the start of the 1997 Fastnet Race: A boat, a skipper and a crew at the height of their powers, with regular success at home and abroad. Photo: W M Nixon

Most recently he has been best known for his stellar campaigns with the Corby 36 Rosie, but we have to remember that by the time the boats left Roy's ownership, they were hugely different from the plans presented by John Corby.

Each winter, the boats would be trailed back to a special spot beside Roy's house, and unless you were in constant attendance you'd no idea of just how much tweaking and surgery was taking place. He brought his brilliant engineer's brain to the challenges of boat performance enhancement, and many are the specialists who experienced that special thrill of anticipation when they got a Monday morning phone call from Roy which simply opened with the quiet announcement: "I've got an idea".

For they could be sure an utterly fascinating project would follow, and even if it involved hours of brutal hard work by volunteers – such as the shifting of the weight configuration in the keel-bulb on Cracklin Rosie – well, Roy was the kind of leader who inspired people to loyal service way over and above the call of duty and friendship.

The home place…..the Corby 25 Rosie club racing at Howth with a trio of Howth 17s.

The home place…..the Corby 25 Rosie club racing at Howth with a trio of Howth 17s.

He was very highly regarded in the marine industry, and renowned sailmaker John McWilliam has been in touch from Australia to tell us that he felt lucky to have done business with Roy over many years, sailing with him and helping him modify the super boats he built – John says his aim was always to stay competitive, and he achieved this target with vision, skill, enthusiasm, kindness – and always a smile.

His generosity was boundless – when he was unable to go on a campaign with Rosie, he always ensured that his crew were encouraged to take the boat themselves, and they achieved many successes in the best Dickson style in events as various as the Scottish Series, Cork Week, and the British IRC Open

The passing of this remarkable sailor and boat-innovator makes us wonder if we’ll ever see his like again. Roy Dickson may have been at the forefront of many developments, but he was a very talented man operating in a pre-specialisation age. Nowadays, the sort of projects he successfully undertook between his workshop and the boat in the garden would be in the province of specialists in highly-equipped air-conditioned premises, yet Roy Dickson managed it all on a “make-it-up-as-you-go-along” basis.

At the 75th Anniversary of Sutton Dinghy Club in 2014 were (left to right) Commodore Andy Johnstone, Olympic helm Barry O’Neill, and 1954 Commodore Roy Dickson

At the 75th Anniversary of Sutton Dinghy Club in 2014 were (left to right) Commodore Andy Johnstone, Olympic helm Barry O’Neill, and 1954 Commodore Roy Dickson

In fact, there’s no doubting he was a very special one-off. He needed personal projects, the more complex the better, and boats and sailing provided them in abundance and brought out his skills in communication – exceptional skills which everyday life didn’t always evoke. The world of sailing has been greatly enriched by his long time in it. And the loyalty and dedication of his numerous friends-as-shipmates – drawn from many places and backgrounds – is eloquent testimony to the effect he had on others when they shared his devotion and enthusiasm.

Our thoughts are with them and particularly with his four sons – David, Alan, Gary and Ian – and their families, in whom the Dickson sailing gene is frequently manifested. Particularly so in the case of Roy’s grandson and Ian’s son Robert Dickson, Ireland’s 2018 Sailor of the Year with Sean Waddilove for their Gold Medal in the International 49er U23 Worlds. It’s for sure that Roy Dickson was a sailing universe whose spirit lives on.

WMN